Transcription

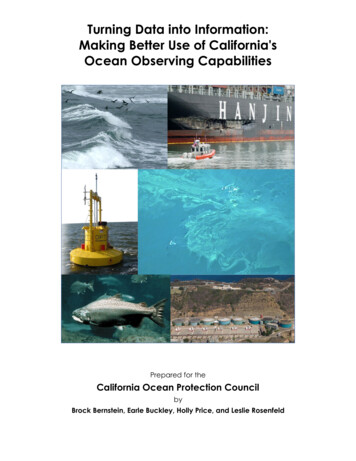

Turning Data into Information:Making Better Use of California'sOcean Observing CapabilitiesPrepared for theCalifornia Ocean Protection CouncilbyBrock Bernstein, Earle Buckley, Holly Price, and Leslie Rosenfeld

Turning Data into Information:Making Better Use of California'sOcean Observing CapabilitiesPrepared for the California Ocean Protection Councilby:Dr. Brock B. BernsteinDr. Earle BuckleyDr. Holly PriceDr. Leslie RosenfeldCover photo credits:Wave: Abe DohertySalmon: UnkownAlgal bloom: Charles J. SmithPoint Loma Wastewater Treatment Plant: California Coastal Records ProjectShip: United States Coast GuardWave energy buoy: Ocean Power Technologies

AcknowledgementsOur efforts benefited from the substantial amounts of time that a number of people spent with us in phoneand email conversations, as well as face-to-face meetings, and from the documents and other materialsthey provided to help fill gaps in our understanding. These people and their affiliations are listed inAppendix 1.In addition, we wish to thank the advisory committee that provided guidance and feedback and helpedfocus our work at critical points in the project.Sheila Semans, Ocean Protection CouncilSkyli McAfee, Ocean Science TrustJulie Thomas, SCCOOSSteve Ramp, CeNCOOSHeather Kerkering, CeNCOOSPaul Siri, Ocean Science Applicationsi

ContentsAcknowledgements . iList of Figures . ivList of Tables . vAcronyms and Abbreviations. viExecutive Summary . viiiSummary of Recommendations for Implementing Agencies . xiInstitutional issues . xiOOS assets needed for multiple management areas . xivKey management areas . xvii1.0 Introduction . 11.1 Project background. 21.2 Project approach and constraints . 31.3 Report structure . 72.0 Institutional Issues. 92.1 Overview of institutional issues and recommendations .102.2 Coordination and governance .122.3 Product development .142.4 Funding and business model .162.5 Management agency roles .183.0 Decision Information Needs: Discharges and Water Quality . 203.1 Discharge issue overview .213.2 Discharge characteristics and impacts .213.3 Discharge management and decision framework .243.4 Discharge information needs .263.5 Discharge institutional issues.293.6 Discharge recommendations .334.0 Decision Information Needs: Salmon Recovery . 354.1 Salmon recovery issue overview .364.2 Impacts on salmon populations .374.3 Salmon management and decision framework .404.4 Salmon recovery information needs.414.5 Salmon recovery institutional issues .444.6 Salmon recovery recommendations.465.0 Ocean Renewable Energy . 505.1 Ocean renewable energy issue overview.515.2 Ocean renewable (hydrokinetic) energy characteristics and impacts .52ii

5.3 Ocean renewable energy management and decision framework .555.4 Ocean renewable energy information needs.585.5 Ocean renewable energy institutional issues .625.6 Ocean renewable energy recommendations .636.0 Decision Information Needs: Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs) . 676.1 HAB issue overview .686.2 HAB characteristics .696.3 HAB management and decision framework .716.4 HAB information needs .756.5 HAB institutional issues .806.6 HAB recommendations .807.0 Decision Information Needs: Oil Spills . 837.1 Oil spill issue overview.847.2 Oil spill characteristics .857.3 Oil spill management and decision framework .887.4 Oil spill information needs .917.5 Oil spill institutional issues .967.6 Oil spill recommendations .978.0 OOS Assets Needed For Multiple Management Areas . 988.1 Develop a long-term commitment to existing modeling efforts .998.2 Link nearshore and offshore circulation models .1008.3 Rigorously evaluate HF radar applications.1008.4 Integrate diverse information and products .1019.0 References. 103Appendix 1 – Information Resources . 108Appendix 2 - Observing System Requirements and Capabilities . 112Discharges requirements, capabilities, and gaps .112Salmon recovery requirements, capabilities, and gaps .117Renewable ocean energy requirements, capabilities, and gaps .124iii

List of FiguresFigure 1.1. Overview of project approach. . 6Figure 3.1. Representative discharge locations and plume configurations. . 22Figure 3.2. A schematic illustration of how ocean data, models, and tools can inform keyaspects of decision making related to coastal discharges. . 27Figure 4.1. Trends in abundance of adult Sacramento River Chinook salmon (escapement) . 36Figure 4.2. The data inputs, models, and model-based tools needed to produce the keyinformation outputs and assessments required for decision making related to salmonrecovery. . 43Figure 5.1. Hydrokinetic Energy Converters – Examples. . 53Figure 5.2. Location of the nine Preliminary Permits (two at Fort Ross) issued by FERC as ofMarch 28, 2011 for WEC projects in California. . 57Figure 5.3. This figure demonstrates how ocean data, models, and tools can inform key aspectsof environmental impact assessment and consequent permitting, licensing, andleasing decisions for ocean renewable energy projects. . 59Figure 6.1. Example monitoring results for the third week of April, 2011, for the volunteer toxicphytoplankton monitoring program. . 73Figure 6.2. A schematic illustration of how ocean data, models, and tools can inform keyaspects of decision making related to HABs. . 76Figure 6.3. Aerial photograph of the August 2010 Tetraselmis bloom off San Diego County insouthern California. 78Figure 7.1. Offshore oil production and transport facilities in Santa Barbara County. . 85Figure 7.2. Fate of oil spilled at sea showing the main weathering processes . 86Figure 7.3. Incident Command System for oil spills . 90Figure 7.4. A schematic illustration of how ocean data, models, and tools can inform keyaspects of decision making related to oil spills. . 92iv

List of TablesTable 1.1. Range of activities and decision types included in the evaluation. . 4Table 3.1. Basic characteristics of each discharge type. . 23Table 3.2. Potential human health and ecosystem impacts from POTW, sewage spill,stormwater, and desalination plant discharges. . 24Table 4.1. Potential impacts to salmon populations from a variety of natural and anthropogenicsources in both oceanic and terrestrial systems. . 38Table 5.1. Summary of the status in California of the five forms of ocean renewable energy. . 51Table 5.2. Possible environmental and ecological effects that could result from WEC projects. 54Table 6.1. Marine planktonic species occurring along the west coast of the U.S. that arepotential concerns for public health. . 69v

Acronyms and S SIHABMAPHABsHFICSIOOSIRJSACMBARIMMCMSPNASAArea Contingency PlanAutomated Data Inquiry for Oil SpillsAreas of Special Biological SignificanceAutomated Information SystemAmnesic Shellfish PoisoningBay Conservation and Development CommissionBiogeographic Information and Observation SystemBureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and EnforcementCalifornia Cooperative Oceanic Fisheries InvestigationsCalifornia Environmental Protection AgencyCalifornia Coastal CommissionCalifornia Department of Fish and GameCoastal Data Information ProgramCalifornia Department of Public HealthCalifornia Environmental Data Exchange NetworkCentral and Northern California Ocean Observing SystemCalifornia Environmental Quality ActCalifornia Integrated Water Quality SystemCoupled Ocean-Atmosphere Mesoscale Prediction SystemCalifornia Coastal Ocean Currents Monitoring ProgramCalifornia Public Utilities CommissionCalifornia Toxics RuleCalifornia Water Quality Monitoring CouncilCoded Wire TagsCoastal Zone Management ActDomoic Acid PoisoningDepartment of EnergyDepartment of Water ResourcesElectric Power Research InstituteEndangered Species ActFederal Energy Regulatory CommissionGeneral NOAA Operational Modeling EnvironmentGenetic Stock IdentificationHarmful Algal Bloom Monitoring and Alert ProgramHarmful Algal BloomsHigh FrequencyIncident Command SystemIntegrated Ocean Observing SystemInfraredJoint Strategic Advisory CommitteeMonterey Bay Aquarium Research InstituteMultipurpose Marine CadastreMarine Spatial PlanningNational Aeronautics and Space Administrationvi

&ROSPAFOSPROSTOWETPFMCPG&EPIERPORTS onal Data Buoy CenterNet Environmental Benefit AnalysisNational Environmental Policy AnalysisNational Oceanic and Atmospheric AdministrationNational Pollutant Discharge Elimination SystemNutrient-Phytoplankton-ZooplanktonNatural Resources Damage AssessmentNaval Research LaboratoryNational Water Level Observation NetworkOuter Continental ShelfOcean Observing System(s)Oil Pollution Act of 1990California Ocean Protection CouncilOffice of Response and RestorationOil Spill Administration FundOffice of Spill Prevention and ResponseCalifornia Ocean Science TrustOregon Wave Energy TrustPacific Fishery Management CouncilPacific Gas & ElectricPublic Interest Energy ResearchPhysical Oceanographic Real Time SystemPacific Ocean Shelf TrackingPublicly Owned Treatment WorksParalytic Shellfish PoisoningRegional AssociationRegional Ocean Modeling SystemSynthetic Aperture RadarSouthern California Coastal Ocean Observing SystemSouthern California Coastal Water Research ProjectSynthesis for Coastal Ocean Observing ProductsScripps Institution of OceanographyState Interagency Oil Spill CommitteeState Lands CommissionSolid Phase Adsorption Toxin TrackingState Water Resources Control BoardTrajectory Analysis PlannerTidal In-stream Energy ConversionTotal Maximum Daily LoadTagging of Pacific PredatorsUnified CommandUS Army Corps of EngineersUS Environmental Protection AgencyUS Fish and Wildlife ServiceWave energy conversionvii

Executive SummaryCalifornia has complex ocean observing systems that gather and analyze extensive amounts of data andare coordinated through regional ocean observing networks. However, the state lacks an overall strategyfor effectively applying its complex network of OOS tools to critical management and decision needs.This results in greater risk from spills, increased economic impacts on coastal resources, and the potentialfor lost economic opportunities due to project delays and conflicts. This report presents the results of astudy, the Synthesis for Coastal Ocean Observing Products (SCOOP), intended to provide guidance forCalifornia decision makers responsible for managing California’s coastal and ocean resources.Over 20 years ago, a National Academy of Sciences report on marine monitoring in southern California(NRC 1990) found that, despite extensive monitoring efforts that were often technically sophisticated, itwas impossible to present a picture of the Southern California Bight as a whole because there was nomechanism for integrating monitoring programs and their results. This finding prompted a coordinated setof efforts, the Southern California Bight Regional Monitoring Program, that is now one of the country’smost productive and cost effective regional marinemonitoring programs. This current report revisited, but at astatewide level, some of the same issues as the earlierNational Academy study. We found a similar set of problemshampering decision making and the effective developmentand use of ocean observing system1 (OOS) tools. The resultis that key risks are not being prioritized and assessed,important economic impacts and opportunities are not beingmanaged, and the status of ocean resources is not beingTrends in abundance of adult wintertracked in a way that enables California to respondrun Sacramento River Chinookadequately to pressures from coastal development andsalmon (source: adapted from PFMCclimate change.2011 and Swanson 2010).For example:A major sewer line break in Thousand Oaks in 1998 discharged hundreds of millions of gallons a dayof raw sewage for many days to creeks and ultimately to the coastal ocean. Managers’ attempts torespond in order to protect human health were limited because of the nearly complete lack ofinformation about the location or direction of the spill. Despite advances in data collectiontechnologies, the refined information products needed for managers to track and respond to this typeof spill are not availableSalmon population declines have created significant impacts on coastal economies throughout muchof central and northern California, with commercial and recreational fisheries completely closed inrecent years. While declines are due to conditions both in the ocean and in streams, salmonmanagement and restoration programs are unable to use OOS data in a coordinated approach thatincludes salmon’s entire rangeThe siting and permitting of coastal desalination plants and offshore wave energy projects hinge onthe ability to reliably assess environmental impacts, yet California lacks an accepted methodology forconducting such assessments or for sharing data across multiple projectsHarmful algal blooms (HABs) are increasing in frequency, as are their impacts on coastal economies,human health, and natural resources. Blooms have the potential not only to cause mass mortalities of1By “ocean observing system” we mean the entire range of data gathering and analysis efforts that includes satellites, ships,autonomous underwater vehicles, aircraft, radars, and human observers, orchestrated by numerous state, municipal, and federalagencies, universities, and private sector entities.viii

marine organisms but also to shut down desalinationplant operations and affect other coastal businesses, butthere is only limited ability to predict blooms and thentrack their movement and extentImpacts from oil spills along California’s coastline couldbe both ecologically and economically catastrophic andspill response is critically dependent on accurateprojections of the spill’s trajectory. Despite this, there isno mechanism for using California’s best source of realtime surface current data (the state-funded highfrequency (HF) radar system) in the official spill trackingmodels used by NOAAThere are three actions California must take to ensure theready availability of OOS data to meet these needs.First, the institutional link between agency decision makersand OOS science and technology must be significantlystrengthened. This will provide much needed strategicdirection to data gathering and the development of usefulinformation products. This can be accomplished byScene from the 1969 Santa Barbaraidentifying a lead statewide coordinating responsibility foroil spill (source:OOS, establishing a dedicated liaison function betweenhttp://www.rense.com/general90/baagency managers and OOS scientists / technologists, andrb.htm)creating a better defined pathway for incorporating new OOSdata and tools into agency decision processes. This willrequire some restructuring of the roles and responsibilities of the two regional observing systemassociations in California, the Southern California Coastal Ocean Observing System (SCCOOS) and theCentral and Northern California Ocean Observing System (CeNCOOS).Second, the responsible agencies for each of the five management issues we examined should address thespecific recommendations highlighted in the following Summary of Recommendations for ImplementingAgencies. These are described more fully in the body of the report and are based on a detailed analysis (inAppendix 2) of the OOS data and information products needed to support specific priority decisions.Implementing these recommendations will require that agencies more systematically base their datagathering and assessment procedures on fundamental management questions and decisions, rather than onmore narrowly defined agency tasks that miss the forest for the trees. A useful model of this approach isprovided by the California Water Quality Monitoring Council, a joint effort of the Natural ResourcesAgency, CalEPA, and the Department of Public Health. The Council has established a structured processfor identifying priority information needs and then creating workgroups drawn from multiple agenciesand user groups to ensure that all the elements of an observing system (e.g., data gathering, data analysis,data management, information products, reporting and data visualization tools) are properly coordinatedto effectively meet management information needs.Third, California must fund the core elements of the OOS capabilities that will enable scientists andmanagers to successfully resolve the types of problems described above. We identify several keycapabilities that cut across multiple issues; some of these capabilities are already operational and someneed further development. For example, the HF radar network is operational but the system is now injeopardy due to a lack of long-term funding. In contrast, the ability to track and/or predict water massmovements, both alongshore and back and forth between the surfzone and the offshore, is crucial toix

virtually every issue we examined, yet there is no organized effort, informed by agency decision needs, todevelop the necessary models.Addressing these recommendations will necessarily require funding, although many recommendationsinvolve a restructuring of existing efforts rather than entirely new ones. However, substantial funding maybe readily available if agency and OOS managers think more creatively. We identify potential fundingsources and alternative funding models that could be used to support a portion of the recommendedefforts. For example, improved OOS capabilities could substantially lower costs for permittees andproject proponents and some of these savings could be recovered in the form of fees or contributions toregional OOS networks.California’s OOS capacity is vital to addressing and resolving key issues facing the state. Developing andsustaining this capacity is neither solely an institutional nor a technical challenge, since both types offactors contribute to and/or inhibit OOS performance. The keystone on which all other recommendationsdepend is the need for coordinated, statewide, strategic direction based on clearly defined managementinformation needs. Without this, California’s OOS efforts will be only partially successful, leavingdecision makers at times scrambling to make do with an incomplete picture of key ocean issues.x

Summary of Recommendations for Implementing AgenciesThis summary highlights key recommendations for those managers in implementing agencies with directresponsibility for managing ocean observing system (OOS) assets and/or for using their data andinformation products in decision making. (Here and throughout this report, we use OOS to refer to thestate’s larger network of ocean data gathering, modeling, and assessment capabilities and not just to theNational Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Integrated Ocean Observing System(IOOS) and its two regional associations (RAs) in California, the Southern California Coastal OceanObserving System (SCCOOS) and the Central and Northern California Ocean Observing System(CeNCOOS)). The following sections present a brief issues summary, followed by key recommendations,for each of the five management areas we examined (discharges, salmon recovery, renewable oceanenergy, harmful algal blooms (HABs), oil spills), as well as for cross-cutting institutional issues and OOSassets.We emphasize that a combination of institutional andtechnical factors affect the availability and utility ofocean information in each of the five management areas.Addressing only one or the other type of factor would beinsufficient; both technical and institutional constraintsmust be concurrently resolved for existing and plannedobserving systems to be fully effective. We alsoidentified a core set of institutional issues at thestatewide level that fundamentally limits the ability of allentities, both public and private, to manage OOScapabilities to meet California’s needs. Addressing theseissues will require sustained leadership by statemanagers. In addition, a key subset of OOS assetsprovide critical data and information across multiplemanagement areas, and thus represent possible prioritiesfor continued and expanded long-term state investment.Framing the Evaluation OOS is more than just CeNCOOS andSCCOOSOOS encompasses a wide range of rawdata and processed information fromstate, federal, local, and private sourcesBoth institutional and technical factorseither contribute to or inhibit OOSperformance and its ability to addressmanagement needsInstitutional and technical factors musttherefore both be addressedWe present initial steps to improve OOSperformance and create momentumtoward broader solutionsIn each of these contexts (i.e., core institutional issues,the five management areas, key crosscutting OOSassets), we identify a number of initial steps that couldhelp improve OOS performance and create momentum toward more fundamental solutions. However, wealso emphasize that these initial steps will not bear fruit without the more fundamental changes to thestatewide institutional context we recommend.Institutional issuesThe key issues that prevent the effective use of ocean data fall into four categories:Coordination and governanceProduct development targeted at decision needsFunding and business modelManagement agency rolesxi

Some issues can be resolved by action within the RAs,but many require action at the statewide level. Inparticular, California must become more engaged withocean observing efforts to create strategic direction,actively guide development, and apply lessons learnedthrough other state programs.Coordination between OOS partners and potentialmanagement users is too often diffuse and ineffectiveand California has no overarching framework forcoordinating ocean observing activities and matchingOOS capabilities with state needs. Existing governancestructures at both state and RA levels are insufficientfor this purpose. This is because state agencies focusprimarily on parts of problems (the silo effect) and theRAs are not well organized for this purpose, nor are theRAs designed, staffed, or funded to fulfill this function.Examples of successful efforts that meet managementneeds demonstrate that these issues can be overcomeand suggest how California could improve OOScoordination. These include several OOS productstargeted at specific users (e.g., port pilots), the StateWater Resources Control Board’s development ofseveral policies that require new monitoring andassessment (e.g., observing) tools, and California WaterQuality Monitoring Council (CWQMC) workgroupsresponsible for organizing statewide data gathering,analysis, and assessment.Critical Institutional Issues California lacks overall coordination of OOSefforts and their relationship tomanagement needsOOS efforts lack a guiding productdevelopment strategy that directs theprocess of turning raw data into usefulmanagement information and toolsRAs are overly dependent on federalfunding and OOS overall does not takeadvantage of potential funding sourcesbeyond agency and grant fundsManagement agency roles are poorlydefined with respect to identifying,developing, and maintaining OOScapabilitiesThere are existing models of success thatprovide inspiration and guidanceThere are initial, low-cost organizationaladjustments that could addressinstitutional constraintsLonger-term, there are opportunities todevelop other sources of fundingCalifornia lacks a consistent, well-defined product development strategy

NDBC National Data Buoy Center NEBA Net Environmental Benefit Analysis NEPA National Environmental Policy Analysis NOAA National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration NPDES National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System NPZ Nutrient-Phytoplankton-Zooplankton NRDA Natural Resources Damage Assessment .