Transcription

SPECIAL THEME: EDUCATION AND OUTREACH IN ECOLOGICAL RESTORATIONEcological Restoration for FutureConservation Professionals: Training withConceptual Models and Practical ExercisesJames Aronson, Nikolay Aguirre and Jesús MuñozABSTRACTIn the context of a new international master’s degree program, “Biodiversity in Tropical Areas and its Conservation,” weled a two-week module on ecological restoration in Ecuador for 34 future conservation professionals from nine nations,including seven from Latin America. One week was spent in the cloud-forest life zone, a second in the lowland tropicalforest. The ranges of biomes and socioeconomic and historical settings that commonly occur in tropical regions werediscussed. We saw these students as future communicators engaged not only in management of protected areas, butalso as deeply involved in outreach, negotiation, and consensus-building among stakeholders. Students were introducedto concepts and techniques for evaluating a degraded landscape in order to determine past and present land uses andconflicts of interest among stakeholders. They were instructed on how to select a reference model using sequential reference sites and to incorporate nine attributes of satisfactorily restored ecosystems into restoration plans. In nine smallgroups, the 34 participating students prepared proposals to obtain funding for a restoration project in their home countries or in one of the two regions of Ecuador that were visited in the module. For this purpose, each group developed aschematic model showing how the target ecosystems were degraded and landscapes fragmented. In a second schema,they proposed a program to restore or rehabilitate different landscape units and to reintegrate fragmented landscapes.Highlights and lessons learned from this modular exercise are presented and discussed.tionraal RestoKeywords: natural capital value, proposal writing, reconcilinglogic and economic development, reference modelsEcoconservationss /UW PreTropical countries are home to theworld’s richest biodiversity, butmost knowledge about those areas isgenerated and published elsewhere—often in more developed “rich” countries and with low returns in terms ofcapacity building or research training in tropical places. In 2008, aninternational master’s program called“Biodiversity in Tropical Areas and ItsConservation” was launched in Ecuador. Its goal is to offer proficient LatinAmerican students the opportunity toreceive a European MS degree in theareas of biology, ecology, forestry, agriculture, and related fields that couldlead to further academic, research,and employment opportunities. SuchEcological Restoration Vol. 28, No. 2, 2010ISSN 1522-4740 E-ISSN 1543-4079 2010 by the Board of Regents of theUniversity of Wisconsin System.programs are scarce in Latin America,and those that exist are usually inaccessible to a majority of the qualifiedstudents. Many students with greatresearch and professional potentialsimply cannot afford the costs ofcompetitive degrees, which wouldaid them in becoming academic orresearch leaders in their home countries. This expertise, in turn, wouldpromote our knowledge of tropicalbiodiversity more quickly.The innovative program we presenthere was created by the InternationalUniversity Menendez Pelayo (UIMP)and the National Research Council(CSIC) of Spain in collaboration withthe Universidad Central del Ecuador(UCE). The government of Spain,through the CSIC, funds the programand provides scholarships to help trainfuture conservation scientists and protected area managers who are workingJune 20104-ER28.2 Aronson (175-81).indd 175or planning to work in Latin America,especially in tropical countries. Thecourse is open to European and othernon-Latin American students as well.Following an organizational modelwidely used in Spain, the MS program’s 19 two-week modules focuson conservation biology, biostatistics, park management, planning andexecuting a research project, and ecological restoration—all centered onthe tropics. Each module is taught byinstructors experienced in their subject areas. Graduating students earncredit towards an MS degree fromUIMP for a course completed in atropical country. Opportunities existfor motivated students to continue ina PhD program in any university inSpain and other European countries,since the program is included in the“European Space for Higher Education.” Additionally, each academicECOLOGICAL RESTORATION28:2 1753/23/10 11:33 AM

year, the CSIC funds provide a fullfellowship for one outstanding student among the graduates to go on toconduct the PhD research in one of itsinstitutes. The program is advertisedthrough its Web site (www.masterenbiodiversidad.org) and also the CSIC,UIMP, and UCE Web sites, along withvarious more informal, although veryefficient, online listservers and forums.In the first year, participantsincluded 24 MS students from sevenLatin American countries, along withthree from Spain and one from theUnited States. Many students alreadyhad considerable background in conservation biology, protected area management, and fundamental ecology,but none were previously exposed tothe science and practice of ecologicalrestoration. Six additional studentsaudited our program. Of varyingages, these students were enrolledin an undergraduate program called“Restoring Natural Capital,” at theUniversidad Alfredo Pérez Guerrero,Extensión Gualaceo.Core ConceptsThe major conceptual issues wedecided to address were why restoreand how to plan, organize, and monitor the progress of a restoration project, with special emphasis on the useof reference models for planning andproject integration within larger biophysical and socioeconomic settings.An additional area of emphasis wasmonitoring and evaluation and theusefulness of the list of “attributes ofrestored ecosystems” (SER 2004) forthose purposes. At the beginning ofthe course, we discussed the difference between restoration and otherenvironmental repair activities. Wenoted that restoration—the process ofassisting the recovery of an impairedecosystem in terms of structure andfunctioning (SER 2004)––differsfrom rehabilitation, which aims atthe recovery of ecosystem processeswithout necessarily the recovery ofthe entire inventory of indigenousbiota. We also explained that both176 June 20104-ER28.2 Aronson (175-81).indd 176restoration and rehabilitation seek is convenient and appropriate to conto recover, reactivate, or return an sider ecological restoration and indeedimpaired ecosystem to a desired state RRR in toto as an effort to restore oror trajectory as embodied by a ref- augment stocks of renewable naturalerence model or reference site (see capital, not only for their inherent,Clewell and Aronson 2007). In con- nonmonetary values, but also to ensuretrast, some damaged sites, with long- or increase flows of ecosystem goodsstanding and widespread alteration of and services. In this approach, theecosystems and where people will be seeming dichotomy between investliving and working on the land indefi- ing in environmental infrastructure—nitely, will be reallocated to entirely yet another name used for renewablenew uses.natural capital—and national or localThe need for reintegration, sensu economic development disappears.Hobbs and Saunders (1992), of frag- Restoring natural capital from this permented landscapes was also discussed. spective means investment in naturalFragmented landscapes require recon- capital stocks and their maintenancenection both ecologically in terms of in ways that improve the functionstheir natural ecosystems and socio- of both natural and human-managedeconomically in terms of their pro- ecosystems, while contributing to theduction systems and built-up areas socioeconomic well-being of peopleat a spatially explicit landscape scale (Aronson et al. 2006, 2007a, 2007b,(see also Hobbs 2002). We introduced 2007c, Clewell and Aronson 2006,the idea of a combined RRR (restora- 2007). Ways to achieve restorationtion, rehabilitation, and reintegration) of natural capital include holistic resmodel. We suggested that for degraded toration of ecosystems, ecologicallylandscapes all three activities should sound improvements to farm lands,be planned simultaneously in order to fish farms, tree farms, and so on, andrecover biodiversity, productivity, and improvements in the utilization ofnatural services of benefit to people.rationextracted natural resources. AdditiontocloseseRlaPlanning should obeloconductedinally, anything that promotes or faciligiccE/ssewith local stakeholders. tates greater knowledge and awarenessW PrUcollaborationWe discussed ecosystem values and of the value of natural capital in dailyparticularly the conflict between the activities also can be considered as aneed to support an agrarian economy form of restoration (Aronson et al.and the concerns for nature conser- 2007b).vation. The article by Clewell andIn order to provide some concreteAronson (2006) on the motivations examples of restoration and rehabilitafor restoring ecosystems served as the tion projects in Ecuador, a very biodifoundation for group discussions on verse tropical country with high levelshow values mold land-use decisions in of human poverty and underdevelopvarious regions and contexts.ment in rural areas, one of us (NA)To complete the introductory por- presented several detailed case studiestion of the course, we introduced the of restoration of abandoned pastures,restoration of natural capital (RNC). which constitute a large part of theWe presented the different forms of unproductive land base in the countrynatural capital (Costanza and Daly (Aguirre 2007, Aguirre et al. 2006,1992, Capistrano et al. 2005), includ- Günter et al. 2007, 2009). For theing biodiversity and well-functioning reestablishment of productive forestsecosystems. We explained that in in these areas, we suggested naturaleconomic terms, renewable natural regeneration on areas with minor discapital can be considered to be a stock turbance, and enrichment plantingsfrom which flow ecosystem goods and or full-scale plantations on land whereservices upon which human societ- natural recovery cannot be guaranteedies rely. We introduced the idea that, or, from a socioeconomic perspective,from a socioeconomic perspective, it that would need too much time toECOLOGICAL RESTORATION28:23/23/10 11:33 AM

recover. At a minimum, projects aimto return the land to more economically productive uses in an acceptabletime period. As Knoke and colleagues(2009) put it:Ongoing discussions on reducingemissions from deforestation anddegradation (REDD), conservationof non-market values such as biodiversity, and integration of deforestation into the international carbonmarkets by means of payments forecosystem services (PES) are condemned to fail, both socially andeconomically, if the local people’sneeds are not taken into account inthat debate. (p. 548)To be effective, restoration in all tropical countries must be reconciled andintegrated with regional efforts aimedat maintaining biodiversity, restoringdegraded ecosystems, and supportingsustainable economic development forlocal farmers, landowners, and communities (Aronson et al. 2006, 2007a,Blignaut et al. 2007, Blignaut andAronson 2008).Finally, we invited students toform small groups to work togetherto prepare short proposals to obtainfunding for an actual restorationproject, either in a familiar region intheir home countries or else in oneof the two regions visited during themodule. We arranged in advance tospend one week with the students inthe cloud-forest life zone near Gualaceo in southern Ecuador and a secondweek in the lowland tropical forest ofeastern Ecuador, in the Amazoniancordillera of Cutucú-Shaimi. Thesetwo locations allowed students toexperience at least part of the broadrange of biomes and of socioeconomicand historical settings that occur in thetropics. These proposals served as thebasis for our evaluations of the students’ work in the module. All studentgroups were asked to present the history of degradation and fragmentationin their study areas and to suggest possible responses from a spatially explicitRRR perspective. Following are somehighlights of the work done in thefield and a discussion of the work oftwo of the student groups.biodiversity. A third of the reserve,however, is moderately modified forestoccupied and used by communities ofShuar Indians.Field WorkCase Studies andPractical ExercisesWe spent the first week of the modulein the Andean town of Gualaceo(Azuay province), which is in the Building a Relevantcloud forest life zone. The region we Reference Systemexamined was representative of vast To guide work and discussion on conareas of upland Latin America, where ceptual issues, we presented a genforest and mineral exploitation, along eral model of ecosystem degradationwith various imported systems of agri- and the three possible responses to itculture and animal husbandry, have (restoration, rehabilitation, and realdrastically altered and fragmented location) at a landscape level, usinglandscapes, even though they still the model of Aronson and coworkersharbor many rare and endangered (1993a, 1993b, Aronson et al. 2007a,plants and animals.2007b), which includes considerationWe took several half-day trips to of ecosystem goods and services as wellobserve the predominantly agricul- as the broad notion of RNC.tural mosaic in the immediate region.Next, we introduced the conceptWe discussed the concept of “read- of reference ecosystems or modelsing” a landscape for clues to the (Egan and Howell 2001, SER 2004,ecological history of land use and Clewell and Aronson 2007, 80–89).misuse. We considered the prospects The advantages of having a referencefor, and obstacles to, ecological res- model were spelled out in terms oftoration at the locations visited. Thisnmonitoring, evaluation, and commutoratio nication to both scientists and stakeseRwas the first time thatmoststudentslagic/ Ecolo explicitly to this holders. To summarize, “Referencehad PbeenssintroducederWUkind of landscape-scale perspective ormodels provide targets towards whichto the meanings and nuances of the to restore and distinguish ecologicalvarious terms relevant to ecological restoration from other kinds of envirestoration.ronmental repair such as rehabilitaThe second week was spent in the tion and species introductions, whichWisui Biological Station in the Cor- do not necessarily return ecosystemsdillera de Cutucú-Shaimi. This newly to historic ecological trajectories”created station was funded by the (Clewell 2009, 244). We discussed theMS program and by the Center for increasingly prevalent idea of restoringConservation and Sustainable Devel- ecosystem processes as an alternative,opment of the Missouri Botanical or complementary strategy, to theGarden. Now it is administered by a use of historical references, and welocal association created for this pur- introduced foundational literature onpose in the Wisui village in collabora- the subject (White and Walker 1997,tion with the MS program, the Uni- Egan and Howell 2004).versidad Central del Ecuador, and theWe then presented a series of mulMissouri Botanical Garden (see www tidimensional reference models that.masterenbiodiversidad.org/wisui.php). serve as goalposts for successive stagesThe station is inside the Cutucú- of ecosystem restoration (Aronson andShaimi Protector Forest, which covers van Andel 2006, Clewell and Aronson312,000 ha of Amazonian forest in a 2007, 81). This approach addressesseries of largely inaccessible mountain- not only biodiversity, but also theous ridges, much of which is nearly flow of ecosystem goods and servicespristine and exceptionally rich in to people, as concurrent and equallyJune 20104-ER28.2 Aronson (175-81).indd 177ECOLOGICAL RESTORATION28:2 1773/23/10 11:33 AM

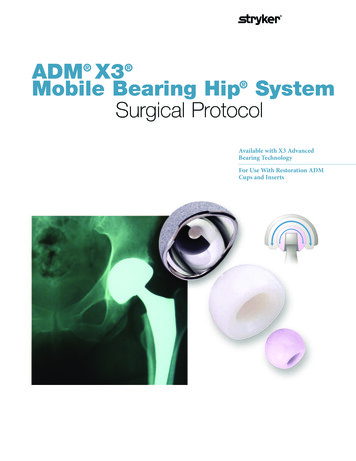

Andes, where subsistence agricultureis the main source of income foralmost everyone. Yet another projectconcerns Mediterranean woodlandsin northeastern Spain, while a fourthaddresses problems related to an oilfield deep in the Amazon. One dealtspecifically with the Gualaceo area andone with the Cutucú-Shaimi cordillera where one of the two week-longfield sessions was held (see sidebar).Notably, each working group found adifferent combination of attributes ofrestored ecosystems to be most usefulfor their proposed restoration projects(see www.rncalliance.org/). In general,they made a selection from the list ofnine attributes proposed in the SERprimer. But two groups also developed an additional list of attributesFigure 1. In this conceptual model of sequential references in ecological restoration, dashed linesrepresent degraded or fragmented conditions as compared to a “whole” system and integratedrelated directly to the delivery of ecolandscapes (from Clewell and Aronson 2007, 81). The inner circles represent the ecosystem. Thesystem services, a novelty that shouldone or two outer circles represent the landscape and the socioeconomic matrix in which thebe incorporated in the next version ofecosystem undergoing restoration is embedded. The triangular appendages represent variousnatural goods and services that accrue from an ecosystem and that grow or decline in size as athe SER primer, in our opinion.function of their use and management by people. Reproduced with permission from Island Press.Feedback was very positive fromalmost all the students who particiessential goals of restoration, especially recommended that the students con- pated in this course. The interactionsin developing countries and indeed sult the nine attributes of satisfactorily among the students from all parts ofall areas outside of parks and other restored ecosystems as outlined in rtheationEcuador and nine different countriestoResseRlaset-aside lands and wetlands.SER (2004) PrimerforEcologicalwere enriching and stimulating for allologiccE/sseW Pr and by Clewell and Aronson of us. The task of writing an integratedUtorationWriting a Grant Proposal(2007).RRR research and development planWe next asked students to break intoWe asked for a detailed five-year proved to be a valuable learning exersmall groups to begin development timetable and a budget. A list of ref- cise both in terms of conceptualizationof draft restoration project proposals erences was also required, along with and in practical skills development.as if they were going to seek funds to appendices as necessary. Nearly all Indeed, several of the groups intendedcarry out real RRR programs. In this students were inexperienced in writ- to pursue funding for their projects.way, they could “learn by doing.” Nine ing a short summary, and thus weComments from the studentsprojects were produced, comprising required all groups to prepare an exec- emphasized the value of working ona cross-section of biomes and ecore- utive summary of no more than 250 an abstract, budget, and timetable.gions that facilitated discussions on words. To orient the thinking about One item that all groups consideredsimilarities and contrasts.interventions, timetable, and budget, essential for success of an RRR proThe main body of the proposals a multiple-reference model was to gram, and that was not adequatelydescribed explicit interventions to be developed, following the general underlined in our initial presentations,be undertaken, including RRR and example shown in Figure 1.was the need for environmental edualso remediation where needed. Thecation (the subject of several papersmethodology for RRR and any socio- Outcomesin this special theme). Outreach waseconomic and educational programsconsidered to be paramount, whetherdeemed necessary was explained. Pro- The nine projects reflect a very broad by the media, workshops, or othertocols for monitoring and data evalu- spectrum of biophysical and socio- formal and informal means of comation as well as anticipated results economic contexts, ranging from munication. The pros and cons ofwere described, followed by products mangroves in the Galapagos Islands, nature-based tourism received much(or “deliverables”), a concept with where high-end, international tourism discussion, as did the search for suswhich most students were unfamiliar. is the main industry in the coastal tainable forestry and agriculture. TheFor monitoring and evaluation, we areas, to páramo grasslands in the high students arrived at a consensus that178 June 20104-ER28.2 Aronson (175-81).indd 178ECOLOGICAL RESTORATION28:23/23/10 11:33 AM

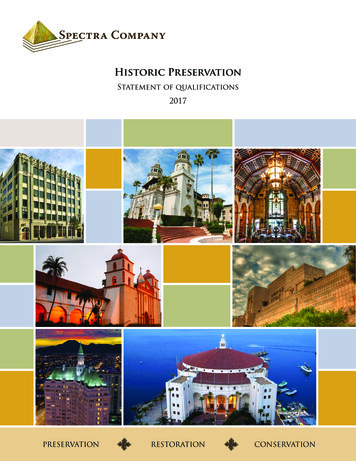

Degradation, Restoration, Rehabilitation, andReintegration in Southern EcuadorEcological transformation processes over10 millennia in the Gualaceo region(southern Ecuador) and proposed interventions, RRR (restoration, rehabilitation, and reintegration), are summarizedschematically in seven stages (see Figure):a) The slopes of Gualaceo dominated byhumid montane shrubland or woodland(matorral) (light gray) prior to the arrivalof humans.b) A relatively small proportion ofthe area is transformed by agriculturalactivities (darker gray) of the Cañarisand—much later—the Inca cultures.With human presence, a socioeconomicmatrix (black) represents the environmental goods and services (triangles)that supported people. The size of thetriangles represents the flow or intensityof use or extraction of natural goods,whose numbers vary over time.Schema prepared by the student group working on the local Gualaceo landscape in Azuay,Ecuador, shows degradation and transformation process over ten millennia, and proposedinterventions to increase the value of natural capital at landscape scale. Original work of DianaFernández, Berenice Trovant, and Josué López. This and other fine examples of student work canbe seen by clicking on RNC Students at www.rncalliance.org.ntoratio thanks to the rapid recovery of the nativel Res by ac) With the arrival of Europeans in the landscape degradationgicisareflectedolocEess / socioeconomic matrix.16th century the transformed areas highlyUW Prperturbedincrease rapidly, as do the urbanized An integrated RRR program would beareas (black dot), while the flow of beneficial.some environmental goods and services also increases, especially timber e) In the first stage of the RRR projfor the construction of houses and char- ect, an increase of the area of matorralcoal for heating. Other environmental is achieved by connecting the existingservices, however, diminish (flow of fragments and replanting selected nativewater, soil conservation, wild foods, species, even though the urbanized areasetc.) The socioeconomic matrix begins continue to expand. Attention is givento degrade, as indicated by the broken to improving the socioeconomic matrix,line representing it.among other things, through improvedenvironmental planning and educad) At the present time, only about 2% of tion. Some environmental benefits,matorral survives in the gorges and other such as soil conservation, begin to showinaccessible areas around Gualaceo; improvements immediately.almost 98% of the area has been transformed to cattle pasture and other farm- f) In the second phase of RRR, the arealand. Environmental services such as of matorral continues to increase thankswater and arable land have been greatly to the implementation of living fencesreduced, and flows of other goods and and various agroforestry activities usingservices are no longer available. The native woody species. In addition, comurban areas have increased. Ongoing munity-based tourism becomes possible,June 20104-ER28.2 Aronson (175-81).indd 179ecosystems with their resident flora andfauna. The urbanized areas continueto grow, but with better planning thenegative impacts of urbanization areminimized and compensated for byinvestments in restoring natural capital.g) In the third and final stage of theRRR project, the area occupied byreconnected patches of matorral continues to increase, even as the urbanizedareas increase. The areas of matorral arenow largely connected by corridors tofacilitate movement of wild organisms.Furthermore, the various environmentalservices increase, especially in relationto water. Both ecological and socioeconomic processes are pursued andmonitored holistically and the socioeconomic matrix is now much morerobust than in the past. The numberand value of environmental services hasgrown considerably.ECOLOGICAL RESTORATION28:2 1793/23/10 11:33 AM

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment.an RRR approach is essential in coun- ReferencesWashington DC: Island Press.tries like Ecuador, Peru, Colombia, Aguirre, N. 2007. Silvicultural contribuClewell,A.F. 2009. Guidelines for refertions to the reforestation with nativesBolivia, Argentina, Honduras, andencemodel preparation. Ecologicalspecies in the tropical rain forestothers from which the students came.Restoration 27:244–246.regionofsouthofEcuador.PhDdisThey agreed that nature conservationClewell, A.F. and J. Aronson. 2006.sertation, Technical University ofcannot be attained in isolation fromMotivations for the restoration ofMunich, Germany.the search for sustainable economic Aguirre N., S. Günter, M. Weber andecosystems. Conservation Biology20:420–428.development.B. Stimm. 2006. Enriquecimiento. 2007. Ecological Restoration: PrinciIn conclusion, the internationalde plantaciones de Pinus patula conples, Values, and Structure of an Emergmaster’s program “Biodiversity inespecies nativas en el sur del Ecuador.ing Profession. Washington DC: IslandLyona 10:33–45.Tropical Areas and Its ignautis well oriented now to offer LatinCostanza,R. and H.E. Daly. 1992. Natand S.J. Milton. 2006. Ecological resAmerican and other students theuralcapitaland sustainable developtoration: A new frontier for conservaopportunity to receive a Europeanment.ConservationBiology 6:37–46.tion and economics. Journal for NatureEgan, D. and E.A. Howell, eds. 2001. TheMS degree that could lead to furtherConservation 14:135–139.Historical Ecology Handbook: A Restoacademic, research, and employment Aronson, J., C. Floret, E. Le Floc’h,rationist’s Guide to Reference Ecosystems.opportunities. In February, the firstC. Ovalle and R. Pontanier. 1993a.Washington DC: Island Press.Restoration and rehabilitation ofyear students finalized the indepenGünter, S., P. Gonzalez, G. Alvares,degradedecosystems.I.Aviewfromdent project reports to fulfill theirN. Aguirre, X. Palomeque et al. 2009.the South. Restoration Ecology 1:8–17.degree requirements, and the secondDeterminants for successful refores1993b. Restoration and rehabilitayear of the program is well under- .tiontation of abandoned pastures in theof degraded ecosystems. II. Caseway. The restoration module will beAndes: Soil conditions and vegetationstudies in Chile, Tunisia and Camercover. Forest Ecology and Managementpresented again, in May 2010, alongoon. Restoration Ecology 1:168–187.258:81–91.similar lines to what has been pre- Aronson, J., S.J. Milton and J.N. BligGünter,S., M. Weber, R. Erreis andnaut, eds. 2007a. Restoring Naturalsented here. We continue to think thatN. Aguirre. 2007. Influence of disCapital:Science,BusinessandPractice.the choices made in terms of coursetance to forest edges on natural regenWashington DC: Island Press.content were and are especially releration of abandoned pastures: A caseevant to the broad educational goals of . 2007b. Definitions and rationale.study in the tropical mountain rainPages 3–8 in J. Aronson, S.J. Miltonthis program, and also provide a usefulnforest of Southern Ecuador. Europeanoitaand J.N. Blignaut (eds), RestoringrtoseRlJournal of Forest Research 126:67–75.atemplate for restoration education thatNatural Capital:ogic Business andolScience,cE/Hobbs,R.J. 2002. The ecological context:ssecould be applied anywhere.Pr Washington DC: Island Press.UWPractice.A landscape perspective. Pages 22–45AcknowledgmentsWe thank Diana Fernández, Berenice Trovant, and Josué López, for permission toreproduce elements of their student project.In Gualaceo, we thank Pepe Portilla, Ingridde Portilla, and the entire staff of EcuageneraS.A., for help and hospitality, as well as JuanPablo Martínez Moscoso, coordinator of theundergraduate degree program on restoringnatural capital, Universidad Alfredo PérezGuerrero, Extensión Gualaceo. We alsowarmly thank Edwin Ankuash Tsamaraint,our guide and helper in Wisui, as well asthe Shuar community there for help andhospitality. Iván Morillo, coordinator of themaster’s program in Quito, and David Neilland Olga Martha Montiel of the MissouriBotanical Garden have been of great helpin making this program possible. ChristelleFontaine, Mrill Ingram, Chris Reyes, AndreClewell, Daniel Renison, and Paddy Woodworth all made helpful comments on themanuscript, for which we are very gratefulindeed.180 June 20104-ER28.2 Aronson (175-81).indd 180Aronson, J., D. Renison, O. Rangel-Ch.,S. Levy-Tacher, C. Ovalle and A. DelPozo. 2007c. Restauración del capitalnatural: Sin reservas no hay bienes niservicios. Ecosistemas 16(3):15–24.Aronson, J. and J. van Andel. 2006. Challenges for ecological theory. Pages223–233 in J. van Andel and J. Aronson (eds), Restoration Ecology: TheNew Frontier. Oxford UK: BlackwellScience.Blignaut, J.N. and J. Aronson. 2008. Getting serious about maintaining biodiversity. Conservation Letters 1:12–17.Blignaut, J.N., J. Aronson, P. Woodworth,S. Archer, N. Desai and A. Clewell.2007. Restoring natural capital: Areflection on ethics. Pages 9–16 inJ. Aronson, S.J. Milton and J.N. Blignaut (eds), Restoring Natural Capital: The Science, Business, and Practice.Washington DC: Island Press.Capistrano, D., C. Samper K., M.J.Lee and C. Raudsepp-Hearne, eds.2005. Ecosystems and Human WellBeing: Multiscale Assessments. Vol. 4 ofECOLOGICAL RESTORATIONin M. Perrow and A.J. Davy (eds),Handbook of Ecological Restoration.Cambridge: Cambridge UniversityPress.Hobbs, R.J. and D.A. Saunders. 1992.Reintegration of Fragmented Landscapes: Towards Sustainable Productionand Nature Conservation. New York:Springer.Knoke,

sustainable economic development for local farmers, landowners, and com-munities (Aronson et al. 2006, 2007a, Blignaut et al. 2007, Blignaut and Aronson 2008). Finally, we invited students to form small groups to work together to prepare short proposals to obtain funding for an actual restoration project, either in a familiar region in