Transcription

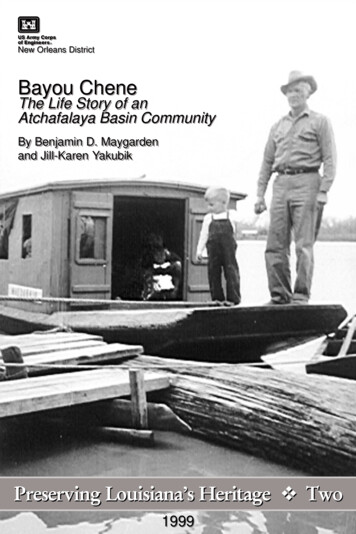

New Orleans DistrictBayou CheneThe Life Story of anAtchafalaya Basin CommunityByBy BenjaminBenjamin D.D. MaygardenMaygardenandand Jill-KarenJill-Karen YakubikYakubikPreserving Louisiana s Heritage v Two1999

New Orleans DistrictServing LouisianaThe U.S. Army Corps of Engineers involvement in Louisiana dates back to1803 when an Army engineer was sent to the newly acquired city of NewOrleans to study its defenses. The Corps early work in the area was of amilitary nature, but soon expanded to include navigation and flood control. Today, New Orleans District builds upon these long-standing responsibilities with itscommitment to environmental engineering.New Orleans District s jurisdiction covers 30,000 square miles of south central and coastal Louisiana. The district plans, designs, constructs and operatesnavigation, flood control, hurricane protection, and coastal restorationprojects. It maintains more than 2,800 miles of navigable waterways andoperates twelve navigation locks, helping to make the ports of south Louisiananumber one in the nation in total tonnage (number one in grain exports). The Corpshas built 950 miles of levees and floodwalls, and six major flood control structures tomake it possible to live and work along the lower Mississippi River.The Corps cares for the environment by regulating dredge and fill in all navigable waters and wetlands, and by designing projects to reduce the rate ofcoastal land loss. Besides constructing major Mississippi River freshwater diversion structures, the District regularly creates new wetlands and restoresbarrier islands with material dredged from navigation channels. The District also chairs the multi-agency Louisiana Coastal Wetlands Conservation andRestoration Task Force, which is planning and constructing a variety of projectsto restore and protect the state s coastal marshes. In addition, the District manages the clean up of hazardous waste sites for the Environmental ProtectionAgency.One important aspect of the New Orleans District program is its historicpreservation and cultural resources management program. The Corps protects a great variety of prehistoric and historic sites to meet the requirementsof the National Historic Preservation Act. The New Orleans District recognizes its responsibilities to communicate the results of its numerous studies tothe public, and this booklet is the second in our series of popular publications.The booklet was prepared in connection with the District s Atchafalaya BasinFloodway, an important component of the comprehensive plan for flood control in the Lower Mississippi Valley. This multi-state plan, called the Mississippi River and Tributaries Project (MR&T) provides flood protection for thealluvial valley between Cape Girardeau, Missouri and the mouth of the river.

BAYOU CHENEThe Life Story of anAtchafalaya Basin CommunityBy Benjamin Maygardenand Jill-Karen YakubikPreserving Louisiana s Heritage v Two1999

Bayou ChenePRESERVING LOUISIANA’S HERITAGEIntroductionThe Atchafalaya River Basinhas changed a great deal in thepast century and a half. Twisting bayous where steamboatstraveled, loaded with barrels ofsugar or towing huge rafts of timber, are now filled with sedimentand grown over with trees.Other bayous, broad lakes andthe Atchafalaya itself have beenstraightened and dredged togreater depths. Willow thicketsnow stand where immense liveoaks and cypress once grew,robed in Spanish moss. Arrowstraight canals crisscross the landscape, ignoring natural terrain.And every year the spring floodsof the Atchafalaya River leavemore silt and sand behind, burying the basin s past further beneath the surface. However,some people can recall a different Atchafalaya Basin. They remember a beautiful environment that repaid hard work withrich harvests of timber, fish andgame. They remember a homewhere their ancestors lived formore than three generations, andwhere they themselves grew up.They remember a small community that no longer exists, butthat still draws them together,like a family, after the passage ofdecades. They remember a placecalled Bayou Chene.2Bayou Chene residents gather beneath the oaks at the Methodist Church to hear thepreaching of Pastor Chase, ca. 1904.3

Bayou ChenePRESERVING LOUISIANA’S HERITAGEChitimacha. The twobattled from 1706 until1718. The French killedor enslaved many of theChitimacha. Only ahandfuloftheChitimacha were left bythe time of the Louisiana Purchase. Their descendants resided alongBayou de Plomb intothe late-nineteenth century, but they moved toBayou Teche nearCharenton by 1900.Colonial PeriodWe do not know when thefirst Frenchman traveling in theAtchafalaya Basin named BayouChêne or Oak Bayou. Whoever it was, Native Americanshad been there first. When theFrench arrived in Louisiana inthe late-1600s, the Chitimachatribe, numbering about 3,000persons, lived in the area stretching from Bayou Teche to theMississippi River. SeveralChitimacha settlements werearound Bayou Chene, includingKa me naksh tcat na mu, onBayou de Plomb, Ku shuh (orKu cux) na mu ( CottonwoodVillage ) on Lake Mongouloisand Na mu ka tsi ( Village ofBones ) on Bayou Chene itself.The precise locations of thesesites are not known.4Contact with the Frenchwas eventually a disaster for theIn the 1700s, the Louisianacolonists usually saw theAtchafalaya Basin as an obstacleto east-west travel rather than asa place to settle. Travelers notedthe area s fine timber, but theypreferred the better farmlandelsewhere in Louisiana. By thelate-eighteenth century, cattleranchers from the Attakapasprairies drove herds of cattleacross the basin to eastern markets. As they establisheddrover s roads across the basin,people became more familiarwith the area s potential forsettlement. Scattered settlementswere established in the basin bythe 1790s, including at least onefamily at Lake Chicot nearBayou Chene. Frenchman C.C.Robin described a trip throughthe Atchafalaya Basin in 1803:.The bayou breaks up into innumerable channels, as it flowsalong, in which one is easily lostif he is not familiar with them.Sometimes, the channel enlargesinto lakes, sometimes it narrowssuddenly and one finds oneself inshadowy avenues, overhung withenormous trees, impenetrable bythe rays of the sun, interlaced withdense vines, and loaded with grayish streamers of Spanish moss,barely leaving room for the passageof the boat. One imagines himselfcrossing the shadowy Styx withAcheron. Alligators in swarmssurround the travelers or are seensleeping everywhere on the shellbeaches. Mixed with the deepthroated bugling of giant frogs.[are] the sharp cries of black cormorants and the melancholy lovenote of the owls.These tall trees are cypresses.Stretching away from us as far asthe eye can see, each cindery column, based upon a broad, deeplyfurrowed cone, crowned withbranches which hardly bend downat all. These columns seem to formthe portico, and one fancies that heis before the immense palace of theGod of the Waters. the mysterious lair of Old Proteus. [Robin1966:184-185]Antebellum Period1804-1861After long sinuosities which forminnumerable islands, among whichthe inexperienced traveler wouldResidents of the AtchafalayaBasin were few at the time of theLouisiana Purchase, and much ofthe basin interior remained unknown. However, in the late1820s and early-1830s, a growingrequire the thread of Ariadne in order not to wander forever, the riveropens suddenly into a magnificentlake of several leagues extent. Thesudden light surprises the travelerand the beauty of the water, set aboutwith tall trees, forms an enchantingsight.demand for agricultural landprompted widespread surveys ofthe area. Parts of Grand Riverhad been surveyed by 1829 andwere settled by the early-1830s.During the 1830s, settlements alsodeveloped on Bayou Grosse Teteand Bayou Sorrel, with plan-The oldestform of boatused in theAtchafalayaBasin was thedugoutpirogue,adapted fromNativeAmericancanoes.5

Bayou ChenePRESERVING LOUISIANA’S HERITAGEabout 30% of thepopulation. Thetotal Bayou Chenearea populationwas about 277 persons. A post officewas established atBayou Chene in1858, indicatingthat the populationwas large and stableenough for officialrecognition.OriginalU.S. landclaimants inthe vicinityof BayouChene,1848.01 mitations following soon after at BayouChene. By 1841, at least 16 planterswere homesteading along BayouChene, Bayou Crook Chene and6Bayou de Plomb. The first claimsof land in the Bayou Chene areawere registered with the U.S.government in June 1848, andnearly all the tracts in the vicinity were claimed by the end ofSeptember 1848. The descendants of many of the originalBayou Chene claimants still livedthere a century later.The 1850 census was the firstto list residents at Bayou Chene;it counted 184 free persons in 41households. Fifty-seven BayouChene inhabitants were FreePeople of Color, accounting for30% of the free population in1850. Many of these Free Peopleof Color migrated out of the areaduring the 1850s. Twelve slaveowners in the area held a totalof 93 slaves, who also constitutedPirogues were traditionally carved from a singlecypress tree. Pirogues began to be built of planks by1920, but cypress dugouts continued in use becausethey outlasted plank-built boats.By the 1860 census, the total Bayou Chene population increased to about 675 persons.Two-hundred and ninety-fourfree persons were listed as resident at Bayou Chene or onnearby bayous. Free People ofColor made up less than 10% ofthe total number of free personsby this time. The 1860 recordsalso indicate that Native Americans composed 5% of the totalpopulation in 1860. These Na-tive Americans were probably inthe area in 1850, but were missedby the earlier census. Therewere about 375 plantation slavesin 1860, outnumbering the freeinhabitants. Several original residents still resided in the area,notably members of the Carline,Falcon, Lafontaine and Verretfamilies. The Allen, Mendozaand Seneca families came into thearea by this time and remainedinto the twentieth century.Bayou Chene planters raisedsmaller amounts of sugarcanethan the great planters along theMississippi River, Bayou Lafourche and Bayou Teche. Mostbasin planters still had horsepowered cane mills when theCivil War began, but a few hadsteam-powered cane mills. AllBayou Chene sugar houses usedold-fashioned open kettles toboil the sugar instead of the moreadvanced vacuum pans. Someother inhabitants were subsistence farmers who also hunted,fished, collected Spanish mossSteamboatstransportedsugar from theAtchafalayaBasin tomarket duringthe antebellumperiod. Manyof the basinwaterwaysthey used havevanished, filledwith sediment.7

Bayou ChenePRESERVING LOUISIANA’S HERITAGEand cut timber. Before 1860,floods ruined some crop years inthe basin, most notably in 1851.Floods became worse after theAtchafalaya was cleared of logjams in 1861, making life moredifficult in the basin.The Civil War In TheAtchafalaya BasinU.S. Gunboat#53 wastypical of theshallow-draft,lightlyarmored tinclads thatbrought theCivil War toBayou Cheneand otherAtchafalayaBasinwaterways.8Basin waterways were considered a route between theUnion forces on the lowerAtchafalaya River and Unionforces in the Baton Rouge area.In turn, Bayou Chene becamethe main route from GrandRiver to Grand Lake, drawingattention to the area. Before attacking Confederate Fort Burton at Butte-à-la-Rose (Butte LaRose), Union troops raided thebasin, confiscating sugar, molas-ses, cotton and firearms frombasin residents. These forays byfederal troops became increas-ingly frequent and made lifemore difficult for Bayou Cheneresidents.Union forces defeated theConfederates at Bisland, GrandLake and Fort Burton in thespring of 1863, giving them control of the Atchafalaya waterways wherever they could operate gunboats. The Confederatescould not match the firepowerof these vessels. Even with thisadvantage, though, Confederateguerrilla forces, as well asjayhawkers and smugglers, constantly harassed the federals, especially in the summer of 1864.Jayhawkers were bands of deserters, draft dodgers and criminals who infested much of Louisiana during the last three yearsof the war. Confederate irregular forces used the familiar terrain of the basin to their advantage, relying uponpirogues, skiffs andhorses in their hitand-run foraysagainst the federals.To deal withthese problems, theUnion commanddecided to destroyall ferries, bridgesand boats in the basin as well as confiscate all contraband goods. Anything not produced locally, including flour, salt and otherstaples, became unavailable toWaterwaysand landformsin the BayouChene vicinitybefore channelalterations inthe twentiethcentury.residents. These policies antagonized local Union sympathizersand hindered the collection ofintelligence. In November 1864,the Union command concededthat small loyal planters in thebasin could keep their boats ifthey were hidden at night from guerrilla thieves. However,the federals still withheld supplies from inhabitants who didnot inform on the guerillas. Ba-sin residents, including familiesat Bayou Chene, also sufferedfrom jayhawker activity into1865.Much damage at BayouChene was the direct result ofmilitary action. Many boats,sugarhouses and stores of sugarwere destroyed by Union gunboats and troops. By February1865, the levee on Grand River9

Bayou ChenePRESERVING LOUISIANA’S HERITAGEwas broken in many places, andthe entire region below BayouPlaquemine was impassable because of flooding. This caused anumber of Union sympathizersat Bayou Chene to leave the basin on federal gunboats. Largenumbers of livestock could notbe saved and were left to drown.The end of the Civil War inLouisiana found Bayou Cheneflooded and abandoned. Thepost office at Bayou Chene hadstayed open through the war butwas officially closed on June 22,1866. It would not reopen forten years.10between 1862 and 1873. Finally,a severe flood in 1874 endedcommercial agriculture in the region. Some former residents canstill remember seeing plantationcane field features in the BayouChene area when they wereyoung. Today, these have allbeen obscured by sedimentationand tree growth.New settlers also moved intothe Bayou Chene area after theCivil War, including at least oneUnion veteran. By 1870, theBayou Chene population totaled277 persons, roughly the same asthe free population in1850. By 1876, thepopulation had grownto approximately 450persons despite the1874 flood. A dramatic change was thedeparture of most African-Americans, themajority of whommoved during the warand Reconstruction.By 1900, not a singleAfrican-American reThe large family of Charles and Agatha Larson, ca. 1897.sided at Bayou Chene.The number of French orBayou Chene from the Acadian families also declinedCivil War to 1907during the late-nineteenth century. Among those that reSome antebellum residentsmained were the Theriot,returned to Bayou Chene afterLandry, Daigle, Verret andthe 1865 flood. For the mostBroussard families. Even a fewpart, planters did not share theEuropean immigrants and firstpost-war recovery enjoyed bygeneration Americans moved tothe sugar growers on the MissisBayou Chene, but most new setsippi River. Only W.W. andtlers were Anglo-AmericansE.T. King produced any sugarfrom southern and northernstates. Family histories relate how people from all overended up in BayouChene. BayouChene offered thesepost-Civil War migrants cheap land (foras little as .25 peracre) where theycould make a livingcutting timber, hunting, fishingor raising livestock.Bayou Chene retained itsfrontier character in this period.Education levels were generallylow, although Oswald Templetestablished a school in the latenineteenth century, holding classin any available building. In thefrontier tradition, a person s pastwas behind them at BayouChene. Former residents indicate that if newcomers behavedthemselves, they were acceptedAn AtchafalyaBasin swamperfloating out alog, ca. 1888.as members of the community,but no one tolerated foolishness. Residents sometimes substituted personal action for distant legal authority. The St.Martin Parish sheriff usually visited Bayou Chene at electiontime, though rarely otherwise.The lumberjacks and othersat Bayou Chene could be a roughcrowd. One newcomer toBayou Chene, Robert Wisdom,was reputedly challenged toprove that he was tough enoughAnAtchafalayaBasin swamperon a choppingboard preparing tocut down acypress tree, ca.1888.11

Bayou ChenePRESERVING LOUISIANA’S HERITAGEA pull-boat ina Louisianacypress swamp,ca. 1900.to stay. A small crowd had gathered at Cyrus Case s store tomeet the steamboat on whichWisdom happened to arrive.Some locals told Wisdom that hehad to fight them or he could notstay in the community. Wisdom rolled his sleeves up and metthe challenge.Luckily, the construction ofrailroads across the region allowed the basin s products toreach distant markets, resuscitating economic development inthe region. The most importantof these basin products in thelate-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries was cypress lumber, which fed into a burgeoning national market for buildingmaterials. By the 1870s, mostmale residents of Bayou Chenewere involved with logging,while a few planted and farmed.12 Float logging was the earlymethod used to cut timber in thebasin. Trees werecut down with axesand saws, and thelogs floated out ofthe swamp duringperiods of high water. Float logginghad little impact onthe vast stands ofcypress in theAtchafalaya regionbecause of the difficult process of removing the logsfromswamps.However, the invention of the pullboat in 1889and the overhead cableway railway skidder in 1892 brought onfull-scale industrial exploitationof swamp cypress. Louisianasawmills produced 248 millionboard feet of cypress lumber in1899, and one billion board feetin 1915. The largest logging company in the Bayou Chene areawas the Schwing Lumber Company of Plaquemine. The steamboat Carrie B. Schwing was a frequent sight at Bayou Chene,towing large rafts or booms oflogs to Plaquemine to be milled.Cypress was rapidly depleted after 1915 and production declined. Large-scale logging wasvirtually over by 1925, littlemore than a single generation af-The Carrie B. Schwing was a familiar site onBayou Chene booming timber to Plaquemines.ter it began. Industrial loggingwas a brief but intense ecological and cultural phenomenon inSouth Louisiana. It greatly affected both the ecosystem of theAtchafalaya Basin and its humanresidents. Removing stands ofvirgin cypress trees rapidly transformed the landscape. Pullboat roads pierced natural levees toA cut-over cypress stand, 1920s.maintain water levels, alteringdrainage in the region. Manypullboat roads, logging canalsand tramways were still visiblein the basin a quarter of a century ago, but many have vanished because of sedimentation.Trapping, fishing and mosspicking remained important toyear-round residents of theAtchafalaya Basin during theboom in the cypress logging industry. Fishing became the most important of theseother activities tothe Bayou Chenecommunity. Thedevelopment ofice-making machines and thetow-car allowedlive fish to be trans-ported to the rail terminal inMorgan City, making commercial fishing in the basin viable.By 1894, state records listed 756 general fishermen in theAtchafalaya Basin.Life at Bayou Cheneca. 1907-1927The golden age of BayouChene may have been the periodfrom the introduction of the internal combustion boat motorbefore 1907 to the disastrous1927 flood. Cypress lumberingstill flourished in the region, andthe inboard boat motor madecommercial fishing more profitable. Only one major flood in1912 and two lesser high-wateryears, 1913 and 1922, damagedhomes, livestock and fields in thebasin. After every major floodsome families left Bayou Chene,but a few new ones would moveinto the area, and a substantialcore of families remained resident through the vagaries offloods and other events. Thepopulation of Bayou Chene in1927 was about 500 persons.The skiff wasone of themajor forms oftransportationin the basinbefore theintroductionof boat motors.Outrigger-likejougs allowedthe rower tostand and faceforward in the push-skiff; a pull-skiff wasrowed whileseated facingbackward.13

Bayou ChenePRESERVING LOUISIANA’S HERITAGEThe CyrusCase house andstore, 1920s.The CyrusCase store waslocated nearthe geographical center ofthe BayouChenecommunityand was long apopularmeeting point.14cooking wood was ash, whichhad a low market value andcould be cut freely anywhere.Many Bayou Chene residents farmed or raised livestockin this period. By the early-twentieth century, no one grew anyquantity of sugarcane at BayouChene, but several farms developed on the extensive tractscleared in the nineteenth centuryfor cane-growing. Residentsgrew corn, potatoes, beans, cabbage and fruit trees, and raisedmilk cattle and oxen, hogs,chickens, turkeys, ducks, geeseand guinea hens. Hogs and cattleranged freely, marked with earnotches. In frontier style, peoplebuilt fences not to keep livestockpenned in but to keep them outof yards and gardens.Some of thehomes at BayouChene, such asthose of JohnSnellgrove, AlbertStockstill, JohnCrowson, Gertrude Tenpennyand Cyrus Case,were large framestructures built in late-nineteenthor turn-of-the-century style.Most houses were more modest.Numerous families lived in tworoom houses, and some lived inone-room houses. Architecturevaried widely. Acadian-stylehouses and shotguns raised onwood blocks were common.Some families resided on houseboats, those of fishermen in particular. Drinking water was collected in cypress cisterns. Onlya few families had brick fireplacesand chimneys; some had traditional stick and mud chimneys.Most families cooked on ironstoves. The favored heating andAmong the important developments in the Bayou Chenelifestyle was the introduction by1907 of the gasoline-fueled internal combustion engine for powering boats. Prior to the introduction of these engines, the average resident of the AtchafalayaBasin owned only a pirogue or apush-skiff. The small earlysingle-cylinder, two-horsepowerengines greatly increased therange of fishermen or indepen-dent loggers. Larger engineswere soon developed. The inboard engines were installed inwhat French-speakers called abateau and English-speakersAnAtchafalayaBasin puttputt.Small, twocycle gasolineenginesrevolutionized life inthe basin bymakingtransportation muchfaster andeasier for theaveragebasinresident.An Atchafalaya Basin houseboat, 1920s.15

Bayou ChenePRESERVING LOUISIANA’S HERITAGEgrocery staples, coal oiland tar, kerosene andgasoline to the basin residents. The fish werebrought to a dock by thefish-boats and thenshipped by rail to urbanmarkets.The puttputt wasmade byinstalling atwo-cyclemotor in abateau or joeboat. 16The adoption of putt-puttscorresponded with strong consumer demand for freshwaterBayou Chene fishermen used a wide variety of fishing techniques. They typicallyfished for catfish with baited lines,using shad, river shrimp or crawfish for bait. Buffalofish wereusually caught in unbaited hoopnets. Fishing lines and nets weremade of cotton, and had to bedipped in vats of hot coal tarabout every two weeks to keepthem from rotting quickly.fish. Fish-boats from the railheads came to the communityseveral times a week, collectingmostly catfish (blue and yellow),buffalofish and gaspergou fromlocal fishermen. They also purchased turtles, alligator skins andfurs. The fishermen kept theirdaily catch in live-boxes of cypress, which were kept submerged. The fish-boats also soldSpanish moss-picking reached its peak during the 1920s when mosswas in high demand forupholstery stuffing.Some moss could be collected as black moss that had fallen to theground and dried out,but it was usuallypicked green. The mosswas quickly depleted nearground level, and harvesters hadto use a longhookedpole from amoss barge,araisedwoodenplatform ona flatboat.The mosscalled a joe boat. The bateauwas up to about 25 feet long,heavy, flat-bottomed, and had ablunt bow and stern. Fitted withthe small Lockwood-Ash, Kellyor Nadler engine, these boats werealso called putt-putts. was laid on the ground to curein large piles. The piles were watered and turned with a pitchfork so that the moss would notcatch fire. Eventually, the mosswas spread out on a fence,wire or tree branches tofinish drying. The outercovering of the moss decomposed, leaving thehorsehair-like core. Afterabout six weeks of curing,the moss weighed 2/3 lessthan it did when picked.The dried moss brought thepicker only about one centper pound. The fish-boatspurchased the cured and baled mossfrom basin residents, taking it toa moss gin. Moss was harvestedat Bayou Chene in large amountsuntil the late-1920s, and in smallerquantities for alonger period.Reminiscentof its early days,Bayou Chenecontinued to be arowdy place.Several saloonsAn Atchafalaya Basin fish-boat. In the 1920s and 1930s, the fish-boatswere often luggers; in later years, large bateaux were often used.operated at various times, mostof them simple barrooms attached to grocery stores. AfterProhibition, some residentsbrewed their own beer, whilePatin s store in Butte La Rosesupplied illicit liquor in the basin. Fiddlers and accordionistsfrom St. Martinville, Catahoula,Butte La Rose and elsewhereprovided music for dances untilthe beginning of the 1930s. Eventhough a minority of the BayouChene population were Acadianor French, the community retained some Acadian cultural influence. The most populardances at Bayou Chene were round dances or roundelays,mazurkas and waltzes; all sharedin Cajun tradition. The presenceof the saloons may have contributed to the rough-and-tumble atmosphere of Bayou Chene inthis period, but drunkenness andfighting were probably no morecommon here than anywhereelse in rural south Louisiana atthe time.The shooting of Joe Carpenter by Nick Burns around 1919Before theintroductionof nylon in the1950s, cottonnets andfishing linehad to betarred aboutevery twoweeks.AnAtchafalayaRiverfishermanhauls a largehoopnet intohis joe boat,1940s.17

Bayou ChenePRESERVING LOUISIANA’S HERITAGERafting outhardwoodlumber, 1920s.Fashionablestudents poseat the BayouChene Schoolcistern, 1926.18has entered community folkloreas an unusual, late example ofviolence at Bayou Chene. Carpenter came to Bayou Chene asan older man and was deemed half crazy. Once a visitor spaton the floor of Carpenter shouse, and Carpenter shot a holein the floor next to the visitor schair. He then ordered thevisitor to spit through the holenext time. Carpenter dislikedthe family of Nick Burns, wholived across Bayou Chene, andsuspected they were stealingfrom his house. One day Carpenter dusted the floor withflour before leaving. Upon returning home, Carpenter foundseveral footprints, and interpreted them as the footprints ofBurns sons. Carpenter proclaimed that he would killBurns family from the littlebaby up to the father, from blond to bald. He asked twofish-boat operators to bring himrifle cartridges from town, buteach gave Carpenter excuses whythey could not obtain the shells. Finally, Carpenterentered a piroguewith a shotgunand began paddlingtowardBurns residence.Mrs. Burns sawCarpenter firstand said she wouldkill him if her husband would not.Nick Burns grabbed his deer rifleand warned Carpenter to turnback. Carpenter answered withfurther threats and obscenities.Burns, a crack shot, fired andhit Carpenter in the chest. Despite his wound, Carpenter continued to paddle toward Burns.Burns fired a second shot, hittingCarpenter in the head and killing him instantly.JohnSnellgrove, Carpenter s employer, interceded with the St.Martin Parish sheriff on Burns behalf, and no criminal actionwas taken in thecase. Coincidentally, Carpenterwas buried next toone of the pastorsof the BayouChene MethodistChurch. Thiscaused a residentto comment thatBayou Chene is the only place inthe world where apreacher and acriminal could be buried side byside (quoted in Case 1973:130131).through the sixth grade. The inboard boat engine enabled morechildren from a wider area to attend the Bayou Chene school,and no later than 1912, motorized school boats or boat transfers were in use. They were apleasant ride in fine weather, butcould be bitterly cold in the winter. In later years, a traditionalprank was for a line of childrenin the boat to hold hands whileone on the end touched theengine s spark plug. The children along the line got shocked.The rough character ofBayou Chene was tamed somewhat during later decades. Thepopulation became more settled,more connected with the outsideworld, and better educated. TheSt. Martin Parish Public Schoolat Bayou Chene was built in theearly-twentieth century, replacing the old one-teacher school.In early decades, the school wentThe great flood of 1927marks the period of decline ofBayou Chene. Most residentsevacuated the area during the1927 flood. Myrtle Burns Biglerrecalled 1927 flood waters reaching seven feet above the bank ofthe Atchafalaya River. SomeBayou Chene residents remainedin the area living on houseboatsduring the flood, but most resi-The Decline of BayouChene, 1927 to 1953Devastatingfloods in 1927,1937 and1947, plus highwater in otheryears,ultimatelypersuadedmany residentsto leave theAtchafalayaBasin.19

Bayou ChenePRESERVING LOUISIANA’S HERITAGEAnAtchafalayaBasin residentpicking mossfrom a skiff,ca. 1948.20dents homes wereon the floodedbanks. A few residents put theirlivestock on hastily-assembled lografts during thehigh water andkept them there aslong as they could,or until the watersubsided. Otherresidents returnedto find four feet ofwater in theirhomes, and builtscaffolds or plankwalks inside theirhouses. BayouChene folkloretells of WarrenStockstill s goatstranded in the MethodistChurch during the 1927 flood.The goat survived weeks of highwater by eating the hymnals andwallpaper in the church. Manyresidents returned to BayouChene after the great flood, butothers l

ages the clean up of hazardous waste sites for the Environmental Protection Agency. One important aspect of the New Orleans District program is its historic preservation and cultural resources management program. The Corps pro-tects a great variety of prehistoric and historic sites to meet th