Transcription

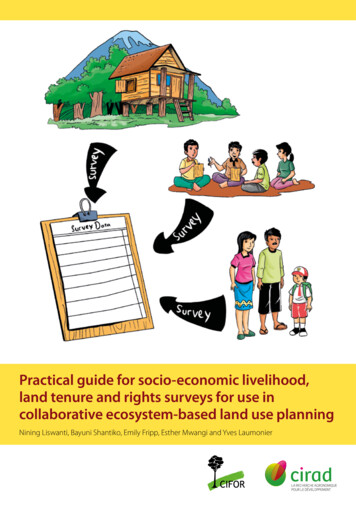

Practical guide for socio-economic livelihood,land tenure and rights surveys for use incollaborative ecosystem-based land use planningNining Liswanti, Bayuni Shantiko, Emily Fripp, Esther Mwangi and Yves Laumonier

Practical guide for socio-economic livelihood,land tenure and rights surveys for use incollaborative ecosystem-based land use planningNining LiswantiCIFORBayuni ShantikoCIFOREmily FrippEFECAEsther MwangiCIFORYves LaumonierCIRAD-CIFORCenter for International Forestry Research

2012 Center for International Forestry ResearchAll rights reservedISBN 978-602-8693-89-9Liswanti, N., Shantiko, B., Fripp, E., Mwangi, E. and Laumonier, Y. 2012 Practical guide forsocio-economic livelihood, land tenure and rights surveys for use in collaborative ecosystembased land use planning. CIFOR, Bogor, Indonesia.Illustration by Pandu Dharma Wijaya (TELAPAK)CIFORJl. CIFOR, Situ GedeBogor Barat 16115IndonesiaT 62 (251) 8622-622F 62 (251) 8622-100E cifor@cgiar.orgcifor.orgAny views expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not necessarilyrepresent the views of CIFOR, the authors’ institutions or the financial sponsors ofthis publication.

Table of contentsPart A: The approachAim of this guideWhat is collaborative land use planning?112Part B: Undertaking socio-economic surveysStep 1 – Survey design, sampling and data requirementsStep 2 – Planning and training the teamStep 3 – Implementation3357Part C: Using the data collectedStep 1 – Data analysisStep 2 – Using the results111213Supporting Notes 1 to 9Note 1 – Key definitionsNote 2 – Sampling techniquesNote 3 – Choosing the most appropriate type of question formatNote 4 – Conducting the surveyNote 5 – Guidance for community meetingsNote 6 – Interview techniquesNote 7 – Focus group discussionsNote 8 – Example questionnaire templates: Household, village andkey informantNote 9 – Experiences from the CoLUPSIA project1516182125272931ResourcesWebsites91923685

List of figures, tables and boxesFigures1 Developing and implementing the survey2 Study villages in the four pilot areas in Kapuas Hulu, West Kalimantan3 Study villages in the five pilot areas in Central Maluku(Seram Island), Maluku88Tables1 Advantages and disadvantages of open questions2 Advantages and disadvantages of partially open questions3 Advantages and disadvantages of closed questions4 Examples of themes and topics for discussion in FGDs5 Socio-economic data required for collaborative land use planning2223243290Boxes1 An example of a briefing note used to introduce the survey teamto a village2 Interview guide3 The role of facilitator283034388

Part A: The approachUnderstanding the socio-economic conditions, land tenure and rights ofcommunities is a critical aspect of collaborative land use planning.Aim of this guideThis guide aims to provide practical steps for field-based practitioners to follow inconducting socio-economic surveys of households and villages, including focusgroup discussions and key informant interviews. This guide is accompanied bynine Supporting Notes. These are essential tools for gathering socio-economicinformation, the results of which can be used as input to collaborative land usedecision-making tools and procedures.Socio-economic survey tools are designed to collect information as a means ofimproving understanding of local resource management systems, resource useand the relative importance of resources for households and villages. Surveysalso provide information on interaction with the government decision-makingsystems and community perceptions of trends and priority issues. Knowledgeabout community-based institutions, which is also obtained, and their roles in thesustainable use and conservation of natural resources, helps to facilitate or reinforcea consensus on land tenure and rights for the region, now and in the future.

2 Nining Liswanti, Bayuni Shantiko, Emily Fripp, Esther Mwangi and Yves LaumonierThus, the use of these tools also serves to highlight possible avenues for conflictresolution between stakeholders. Conflicts over resources often arise in the absenceof a clear boundary and respect for institutional arrangements for the land.What is collaborative land use planning?Collaborative land use planning involves working with all stakeholders –government, local communities, private sector and other relevant individuals – toensure that the land is used sustainably, avoiding negative impacts or threats fromenvironmental degradation and forest loss while ensuring that the social andeconomic considerations of all users are accounted for. With particular respect tocommunities, collaborative land use planning therefore has the following aim:To ensure that land use planning decisions are made with consideration of localcommunities’ opinions, land use needs and socio-economic conditions (opportunitiesand constraints), including rights of access to and use of land.The first step in this process is to engage local communities. This can be achievedthrough the use of household and village surveys, in conjunction with focus groupdiscussions. This is an important way of positively engaging local stakeholders inthe planning process and in ensuring that local voices are heard. Surveys and focusgroup discussions also provide a way to gain a thorough understanding of localpeople’s relationship with the relevant resources – economic and social – and theirlegal rights and access to the use of resources. This information is imperative foreffective land use planning, that is, planning that will work in practice and thatmeets local needs, thus potentially avoiding conflict among people over resources.Key terms are defined in Supporting Note 1.

Part B: Undertaking socioeconomic surveysUndertaking household and village surveys and focus group discussionsin order to understand livelihoods, tenure and rightsStep 1 Designing thesurvey Design, samplingand datarequirementsStep 2 PlanningStep 3 Implementation Planning andtraining the team Key informantinterviews Householdsurveys Focus groupdiscussionsFigure 1. Developing and implementing the surveyStep 1 – Survey design, sampling and data requirementsWhen conducting a survey, the first step is to determine the objective and purposeof the survey. This will provide the framework for the content and scope ofthe survey work and be used to help identify which kinds of stakeholders andcommunities are to be surveyed.Data requirements and survey designThe data to be gathered through the survey process will need to reflect the purposeof the survey work. In developing the survey, other considerations are the lengthof time for the interview and thus the resources (financial, human) needed toeffectively conduct the surveys, enter the data and analyse the results.Different tools (surveys, discussions, interviews) are used to obtain different typesof information from different groups of informants. For example, householdsurveys can be used to gather information on age, gender, education, incomesources (agriculture, forest and employment), perceptions of change in landuse and access to forest resources. By contrast, understanding of the functions(governance and institutional) of the village, development, broader issues onaccess to land, population growth, social conditions and constraints can be gainedthrough focus group discussions and interviews with key informants. These surveymethods are explained in Step 3: Implementation.

4 Nining Liswanti, Bayuni Shantiko, Emily Fripp, Esther Mwangi and Yves LaumonierWho should be included in the survey(s)?The individuals and communities to be surveyed should be decided whenconsidering the objectives and purpose of the survey. Different individuals orgroups of individuals will be interviewed depending on the data needed. For ahousehold-level survey, a representative of the household should be interviewed,but the village head or traditional leader will be interviewed in a key informantinterview. Focus group discussions will include members of the community, withgroups formed based on age and gender. More details are in the sections below.Random sampling and sample sizeThe sample size needs to be sufficient to ensure that the survey results will bestatistically relevant. However, in many cases, the sample size also has to bebalanced with the available resources – financial, human and time.Random sampling is used to ensure that the sample is representative of thestudy area, while avoiding bias in the results and ensuring that all elements ofthe population have an equal chance of being interviewed. There are a numberof approaches to determining a random sample, e.g. systematic, stratified and

Practical guide for socio-economic livelihood, land tenure and rights surveys 5clusters. For the purposes of collaborative land use planning, a simple randomsample approach is sufficient (Supporting Note 2).Types of questionsFor all interview types (household interviews, focus groups and key informants),questions can be structured and asked as open, closed or partially open questions.The type of question used will depend on the information that is being gathered.There are advantages and disadvantages of all question types (Supporting Note 3).Through an open question, such as ‘Why has the paddy rice harvest declinedthis year?’, the interviewer can uncover the meaning behind an answer, allowingrespondents to provide examples and explain their answer. These questions aremore time-consuming to administer and analyse. Open questions can be difficultto ask and interpreting the responses can be complex, so training is essential.A partially open question, such as ‘Consumption of forest products has increased,because ’ requires the respondent to elaborate on any answer given. Theadvantages of these questions are that they are quicker and easier to ask and toanalyse than open questions, but the interviewer may miss some informationbecause of the lack of an appropriate category or the level of detail in theresponse. To avoid these problems, the respondent’s answers should be recordedin full, and the interview should repeat the question if the respondent hasanswered insufficiently.Closed questions, such as multiple choices or yes/no answers, are used when keyinformation is required, without the need for further explanation or in-depthunderstanding of the answer or issue. These questions are quick to ask and toanalyse; however, the answers may result in a lack of depth and clarity.Step 2 – Planning and training the teamA well-trained and experienced team is essential for the success of any socioeconomic survey. Previous practical experience is a great asset to the team, withrelevant technical knowledge in socio-economics, forestry and natural resources,for example.All members of the team will require rigorous and robust training in all typesof survey (household, village, focus groups, key informant interviews) to beconducted. All members of the team should have a thorough understanding of theaims of the work and the meaning of every question to be asked. A combinationof classroom and field-based training will provide the best understanding of survey

6 Nining Liswanti, Bayuni Shantiko, Emily Fripp, Esther Mwangi and Yves Laumonier

Practical guide for socio-economic livelihood, land tenure and rights surveys 7methods and procedures. In addition, field training is very useful for checking thesurvey questions and means of data collection, thus providing an opportunity tomake any necessary revisions to the survey and interview questions and procedures.Consideration should also be given to the division of tasks between teammembers – facilitator, resource manager, observers/recorders, team leader.Thorough preparation (designing the survey work, training the team, etc.) andscheduling the survey work are essential for a successful survey (SupportingNote 4). Preparation of the survey team and agreeing on the work plan andtimeframe for completing the surveys should be finalised in advance. Villagesshould be given due notification prior to survey work and permission to conductinterviews should be sought and granted.Step 3 – ImplementationSurvey approaches vary. Different approaches are used for different purposes. Forthe purpose of collaborative land use planning, three survey methods are used: Key informant interviews Household surveys Focus group discussionsBefore commencing any survey work, a community meeting should be held.Community meetingsA community meeting is a valuable and productive way for the survey team tomeet with the villagers, explain the survey work – its aims and approach – andensure that all members of the community understand the expected outcomes ofthe survey work (Supporting Note 5). A decision to conduct a community meetingshould be made only after meeting the community or village head. If possible, thevillage head can then help set up and conduct the community meeting.Key informant interviewsKey informants are individuals who are deemed to have knowledge of particularissues. Key informants will provide the interview team with detailed informationand, importantly, interpretation of key issues that other members of thecommunity may not be able to provide. Potential key informants should beselected, in consultation with the village head, traditional leader or head of clan,for an in-depth interview with the survey team (Supporting Note 6).

8 Nining Liswanti, Bayuni Shantiko, Emily Fripp, Esther Mwangi and Yves LaumonierVillage and household surveysVillage and household surveys are used predominantly to collect quantitative andqualitative data, through structured interviews with the head of the household,using both closed and open questions. Survey forms for both household- andvillage-level surveys are designed to gather specific information, relevant to thesurvey objective, as discussed above.Focus group discussionsA focus group discussion aims to elicit in-depth information on the concepts,perceptions and ideas of a group of 6–12 people. Ideally, a focus group discussionis an iterative process, whereby each discussion builds on previous discussions bydeveloping a topic or emphasis on certain aspects (Supporting Note 7).In the context of a collaborative land use planning project, a focus groupdiscussion could include discussions on institutional arrangements, communityrights, community access to forest, the use of forest by the community andsustainable management of forest resources

Practical guide for socio-economic livelihood, land tenure and rights surveys 9Key to the success of the focus group discussion is the presence of a strongfacilitator who will stimulate discussion and ensure that it is aligned with theobjectives of the survey team.It is beneficial if other research instruments such as key informant interviews, indepth interviews or other qualitative techniques are used in conjunction with focusgroup discussions.Survey forms used for household and village surveys, key informant interviews andfocus group discussions are reproduced in Supporting Note 8.

Part C: Using the data collectedAnalysis and use of the collected data should reflect the objectives of the surveyThe extent of analysis and use of the data collected will depend on the surveyobjectives and expected end uses. For collaborative land use planning, the surveyresults will provide, first, a robust baseline of socio-economic factors related toland resources and their use; and second, detailed insight into the communityinstitutions, their relationship with land use planners (e.g. government bodies) andany potential areas of conflict. Together, this information can be used to developcollaborative land use decision-making tools.

12 Nining Liswanti, Bayuni Shantiko, Emily Fripp, Esther Mwangi and Yves LaumonierStep 1 – Data analysisThe choice of method for data analysis will depend on the volume of data collectedand the expected uses of the findings.Where household- and village-level surveys are conducted, significant volumes ofdata will be collected. Analysis of this volume of data is usually done in a statisticalpackage such as SPSS. Using such packages also allows the data to be entered andcleaned before analysis. Data may be exported to other software packages such asMicrosoft Excel for further analysis and for preparation of tables and graphs.For more qualitative information, gathered, for example, from focus groupdiscussions and key informant interviews, data analysis is based primarily onGlaser and Strauss’s Grounded Theory Method. This method of analysis drawsout a list of categories within and across the research question items and varioussections of the survey instrument to identify key themes, separately for the focusgroup discussions and key informant interviews. The results are then importedinto nVivo, qualitative data analysis software. A hierarchical coding schemeis developed, based on the initial list of categories, to reflect the key researchquestions, and shape further by themes that emerge from the data. The data arethen coded according to the themes identified. For the focus group discussions,to disaggregate findings by gender, age and location, the data are also coded using‘case’ codes, with a separate ‘node’ created for each of the interviews. A range ofadvanced coding queries is used to analyse patterns, trends and responses to variousquestions in the survey. The results of the queries are exported into MS Word andanalysed to write those parts of the report that summarise the findings and identifypatterns and trends in the data.The final analysis will need to reflect the original aims and objectives of the survey.To help structure the analysis, research questions can be developed, such as: How important is access to forest resources for the livelihoods of communities? Are the poorest communities more or less dependent on forest resources thanother groups? How do access to forest resources and the resulting livelihood implicationsvary across the survey sample, e.g., a district? How do land ownership, tenure and user rights affect the livelihoods ofcommunities?

Practical guide for socio-economic livelihood, land tenure and rights surveys 13Step 2 – Using the resultsThe use of the results from the survey will again depend upon the objectives. Forcollaborative land use planning, the results will be used not only as baseline databut also to highlight the issues – constraints and opportunities – that communitiesencounter with regard to land use and the potential mechanisms for addressingthese issues. Robust baseline data can be combined with biophysical data toprovide a thorough overview of the situation within the study area (e.g. district).Understanding the communities and their internal and external (e.g. governmentbodies) relationships will provide a good foundation for developing processes forengaging communities in collaborative land use decision-making processes.Experiences from CoLUPSIA are described in more detail in Supporting Note 9.

Supporting Notes 1 to 9PurposeTo support the ‘Practical guide for socio-economic livelihood, land tenure andrights surveys for use in collaborative ecosystem-based land use planning’, a seriesof Notes have been prepared. The Notes provide additional information andguidance, designed with the aim of assisting field practitioners in carrying outsocio-economic surveys.The Notes are based on experience gained from the CoLUPSIA project. They arenot exhaustive in their content, but they aim to cover the key points identified andlessons learned during the course of the survey work completed in two districts(Kapuas Hulu and Central Maluku) in Indonesia, for 1366 households in total.Together the Practical Guide and Supporting Notes, including examples ofquestionnaires used, form a Socio-economic Tool Kit. The Tool Kit is available onthe CoLUPSIA website for download as a whole kit or as individual documents.

16 Nining Liswanti, Bayuni Shantiko, Emily Fripp, Esther Mwangi and Yves LaumonierNote 1 – Key definitionsTo support the development of socio-economic questionnaires and administrationof surveys, it is useful to fully understand the key terminology.Access to land‘Access to land’ can be simply defined as the ways in which people can have accessto, or use, the land. In rural areas, land access is often based on custom, that is,local traditions and the ways in which community leaders assign land use rightsto community members. Land access can also be obtained by purchasing, leasing,sharecropping, inheriting or squatting illegally on land.Closed questionsA question format that limits respondents to a list of possible answers; closedquestions can be answered with either a single word or a short phrase.Definition of ‘forest’1 Forest is a unit of ecosystem in the form of lands comprising biologicalresources, dominated by trees in their natural forms and environment, whichcannot be separated from each other. Forest area is a certain area that is designated and/or stipulated by governmentto be retained as permanent forest. State forest is a forest located on lands subject to no ownership rights. Adat forest is a state forest located within a customary jurisdiction. Production forest is a forest area whose main function is to produceforest products. Protection forest is a forest area whose main function is to protect lifesupporting systems for hydrology, thus preventing floods, controlling erosion,preventing seawater intrusion and maintaining soil fertility. Conservation forest is a forest area with specific characteristics, with the mainfunction of preserving plant and animal diversity and the forest ecosystem.1According to Law 41/1999 (Indonesia).

Practical guide for socio-economic livelihood, land tenure and rights surveys 17HouseholdA ‘household’ is defined as 1) a group of people who live under one roof andhave close or distant family relationships; 2) the use of one kitchen or stove whereindividuals eat together and share expenses for food and drink (more than 30% ofindividual incomes); or 3) a residence where a group of individuals share unpaidlabour, production and consumption.Livelihood‘Livelihood’ refers to a person’s capability to live, in terms of finances, foodand assets.Land tenure and rights‘Land tenure and rights’ refers to an institutional arrangement that is used tomanage the relationship between individuals or groups of people and the landeither legally or customarily defined.Open-ended questionsUnstructured questions in which possible answers are not suggested; therespondent gives a long answer in his or her own words.Partially open questionsSimilar to open-ended questions, but some answers are pre-categorised to facilitaterecording and analysis.Study of livelihoods, land tenure and rightsIn simple terms, the ‘study of livelihoods, tenure and rights’ is about learning howlivelihoods have been shaped by land tenure and rights and how the communityconducts resource management in the area.Tenure security‘Tenure security’ is the certainty that a person’s right to a certain area of land willbe recognised by others and protected in the case of specific challenges. Peoplewith insecure tenure face the risk of their right to land being threatened bycompeting claims, or even lost following eviction.

18 Nining Liswanti, Bayuni Shantiko, Emily Fripp, Esther Mwangi and Yves LaumonierNote 2 – Sampling techniquesDetermining a sample sizeThe appropriate sample size ultimately depends on the purpose of the study. Forexample, a population census will require 100% participation, and hence thesample size must equal 100%. Factors such as the available resources (time, budget,human) will affect the sample size but care should be taken not to jeopardise thestatistical relevance of the sample.To determine the survey sample size, a simple percentage approach can be used, forexample to interview 5% of the total number of households. Alternatively, a fixedminimum number of respondents can be used as the basis of the sample size.For CoLUPSIA, the sample size was determined using a simple percentageapproach (e.g. 5% of the total number of households) or using a fixed number ofrespondents approach (30 households) in each village. This resulted in 566 and800 households in Central Maluku and Kapuas Hulu, respectively, being surveyed.This represents more than 5% of the total households or above the acceptableminimum number.Determining a random sampleTo determine the size of the sample to be surveyed using a random sampleapproach, take the following steps.1. Identify and list the entire population of the village (e.g. with the name of thehousehold head, village X) and number these 1–250.2. Determine the desired sample size (e.g. 50 households).3. Use whisk social gathering or generate random numbers from a computer toselect the 50 households.4. List the remaining households (e.g. 200 households), and then create a secondlist as Plan B, in case any of the originally selected households are unavailableor unwilling to participate.Following are some tools for random sampling.1. Whisk social gathering. This is the most convenient method, and materials areavailable in the field. Write down, on individual pieces of paper, the numberof each household or representative group. Place the pieces of paper in acontainer, shake it and then pick out the required number at random.

Practical guide for socio-economic livelihood, land tenure and rights surveys 19

20 Nining Liswanti, Bayuni Shantiko, Emily Fripp, Esther Mwangi and Yves Laumonier2. Calculator. If possible, bring a scientific calculator equipped with a randomnumber generation function and take the following steps to generaterandom numbers.a. Specify the total population size (e.g. 50 households).b. To get a random number between 0 and 50, press the random function onthe calculator and multiply by 50; that is, press ‘ran#’ then *50.c. The random number appears as a decimal; whole numbers can be obtainedby rounding or by removing the decimal number (trunc) (e.g. 12.6342:round 13; trunc 12).d. Repeat steps 2b and 2c until the number (n) of the sample is drawn.3. Computer program. If available, random numbers can be generated in theMicrosoft Excel program, as follows.a. Type the general formula for random numbers: rand()b. Repeat steps 2a, 2b and 2c. If using rounding to derive whole numbers,the formula is round(50*rand(),0). If removing the digits after thedecimal, the formula is trunc(50*rand()).Please note that the function ‘rand()’ is very sensitive in Excel: every time thecursor is moved, the random numbers will change. After the random numbers aregenerated, the list of random numbers generated serves as the first list. To copythe list without changing the value of the random numbers generated, use thecommand Copy Paste Special Values.

Practical guide for socio-economic livelihood, land tenure and rights surveys 21Note 3 – Choosing the most appropriate typeof question formatWhen designing a survey and conducting an interview, it is important to considerhow a question can be structured, that is, whether it should be open or closed,or a mixture of both. The type of question and way that it is asked will affect theanswer provided.In general, questions can be either open or closed. The main difference betweenthese two types of question is that open questions allow respondents to explaintheir answers, whereas closed questions do not.With closed questions, respondents do not have the freedom to give an answerother than those provided in the list of questions. Partially open questions can alsobe used when conducting socio-economic surveys.A survey/questionnaire will use a range of question types to ensure that theinformation is obtained in the most appropriate manner.Open questionsOpen questions – exampleWhat is your opinion about the paddy rice harvest this year? Why has it declined?Open questions provide no options for possible prompts or answers and therespondent is able to answer completely freely.What can we learn from this type of question? Open-ended questions have bothadvantages and disadvantages, as detailed in Table 1.

22 Nining Liswanti, Bayuni Shantiko, Emily Fripp, Esther Mwangi and Yves LaumonierTable 1. Advantages and disadvantages of open questionsAdvantagesDisadvantages The interviewer can elicit moreinformation and possibly uncovernew information that had not beenpreviously considered. The interview records can be used inthe report as interesting illustrations. The responses provide additionalscope for analysis and allow a newinterpretation of the conclusions. The interviewer needs experience tobuild discussion of particular topicsand record the findings. Data analysis requires expertise and alot of time.To mitigate the disadvantages of open questions, those conducting the survey orinterview can: Train interviewers and provide direction for ongoing tasks to improve thequality of the data collected. Prepare a list of questions that allow interviewers to systematically explore therespondents’ answers. Use open questions in training sessions with the team members.Partially open questionsPartially open question – example:Over the past 5 (five) years, the amount of forest products consumed byhouseholds has:a. increased, because.b. decreased, because.In a partially open question, the answer is available as part of s category. Hence,the respondent is given a choice of responses: in the example above, the responseis either ‘increased’ or ‘decreased’ (closed), but the respondent is given theopportunity to explain his or her answer provided using ‘because ’ (open).This type of question also has advantages and disadvantages, as set out in Table 2.

Practical guide for socio-economic livelihood, land tenure and rights surveys 23Table 2. Advantages and disadvantages of partially ope

Step 2 - Planning and training the team 5 Step 3 - Implementation 7 Part C: Using the data collected 11 Step 1 - Data analysis 12 Step 2 - Using the results 13 . 2 Study villages in the four pilot areas in Kapuas Hulu, West Kalimantan 88 3 Study villages in the five pilot areas in Central Maluku (Seram Island), Maluku88