Transcription

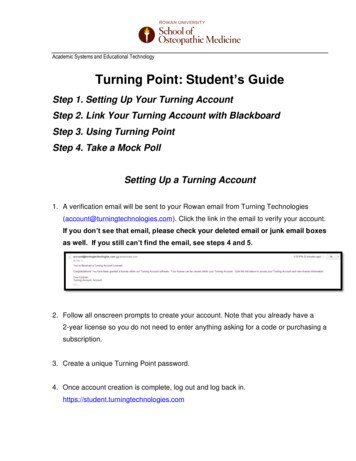

The turning pointA new economic climatein South AmericaMay 2022

ForewordOver the past century, South America’seconomies have benefited substantially fromfossil-fueled industrialization and carbonintensive agricultural expansion. This hasled to the false belief that economic growthand poverty alleviation is incompatible withmeaningful climate action.However, this path is no longer viable for a sustainableand prosperous society. Rising temperatures, and thuschanges in climate patterns, will rapidly translate intoeconomic and commercial losses; directly impactingour land, our infrastructure, and most importantly,our people.The pandemic we are living through has onlyreinforced this awareness. As a global society, we sawour systems tested by COVID-19 and we saw some ofthem fail. This has been a wake-up call, an opportunityto reset and consider the actions we need to take toprotect the shared infrastructure and societal systemson which we rely.Climate change will similarly disrupt our supply chains,test our institutions, and create deep changes insociety. Damages caused by climate crises are alreadybeing strongly felt in South America, causing loss oflives, destruction of urban infrastructure, imbalanceof natural ecosystems, and hopelessness. But there isanother way.This report from the Deloitte Economics Instituteshows a feasible, coordinated, and phaseddecarbonization pathway that leads to new growthfor South America. The analysis starts by accountingfor the costs of global climate change within SouthAmerica’s growth projections and compares that tothe potential economic benefit to the region if theworld achieves net-zero by mid-century.In South American countries, where different cultures,inequalities, and contradictions mark local societies,this transformation period is likely to be complex.Where regional leaders can make a choice is inidentifying the opportunities of the change, innovatingahead of the needs, and collaborating to achievesystemic results.Transitions are always challenging but reversingclimate change is a global imperative. We now mustwork together—governments, businesses, NGOs—to develop and implement the kind of innovativesolutions this time requires.It is up to each of us to decide if we are bold enough tohelp lead the way.Punit RenjenAltair RossatoRicardo BriggsGlobal ChiefExecutive OfficerChief ExecutiveOfficerChief ExecutiveOfficerDeloitteDeloitte BrazilDeloitte Chile

Contents02Key insights07Key terms08Economics for a new climate15The costs of climate inaction22Economic dividends of action26Phases of decarbonization33New economic potential35Endnotes37Related content38Acknowledgments40Deloitte Economics Institute1

Keyinsights2

Key insightsFrom the increasing frequencyof extreme weather events tothe warnings from scientificcommunity, the climate imperativeis now clear: If we do not act tocurb climate change this decade,every industry, region, andcommunity will feel the severeconsequences of that choice.Yet most economic models still don’t depict thesignificant—and growing—costs of climate changeon the economy. This means decision-makers are notable to fully assess the consequences of their choicesbecause the traditional models seem to imply thatthe status quo is somehow the less costly choice foreconomies. It’s time to change that assumption.In this report, the Deloitte Economics Institute (the“Institute”) presents a new way to think about SouthAmerica’s economic future, based on scenarioanalysis from Deloitte’s Regional Climate IntegratedAssessment Computable General Equilibrium Model(D.Climate).If the world doesn’t achieve net-zeroby mid-century, South America willbe among the worst-affected regionsof the world.Without global action, carbon emissions andtemperatures will continue to rise1 to 3 C by the endof the century. In this world, South America would lose12% of GDP—or US 2 trillion—in 2070 alone. A loss ofthis scale is more than the current economy of Brazil.This prospect threatens to worsen the extreme socialand economic inequalities that already exist in mostcountries in the region.However, the risks are not just environmental.South America’s economies have worked hard to buildglobal prominence through the export of primaryresources and manufactured goods. Progress todate could be rapidly undone as key export marketscommit to net-zero targets and greater scrutiny isplaced on supply chains.By explicitly accounting for the impacts of climatechange on future productivity, economic output,and growth, Deloitte’s framework sheds light ontwo pressing questions in the climate policy debate:First, “What would be the economic costs of climateinaction for South America?” and “What are theeconomic benefits of limiting global warming toclose to 1.5 C for South America?” The results alsoshow how decarbonization can help South Americareduce climate-related risk, transform its regionaleconomy, and achieve long-term growth. The followingsummarizes the key insights from this analysis.3

The turning point – A new economic climate in South AmericaUnchecked climate change willcreate a long-term drag on economicgrowth in South America.By 2070, unchecked climate change could createapproximately US 17 trillion in total economic lossesto the South American region (in present valueterms),2 according to Deloitte’s analysis. In this climatedamaged future economy modeled by Deloitte, therecould also be 18 million fewer jobs available in SouthAmerica’s economies in 2070, diminishing the region’slong-term economic prospects.Not only would the economic loss be severe, butthe composition and quality of long-term growthwould also change, threatening South America’sprogress toward diversifying its economies beyondnatural resources. Over the next 50 years, services,manufacturing, retail, and tourism could incur thegreatest losses to economic activity due to climatechange. Together, these industries currently accountfor just over 80% of employment in the region.The public and private service sectors are particularlyexposed to heat stress and human health impactsfrom climate. Over the next 50 years, uncheckedclimate change would reduce South America’s servicesgross value added by US 7.1 trillion in net presentvalue terms. Extreme weather events and damagedphysical capital would reduce South America’smanufacturing output by US 3.5 trillion by 2070. Theretail and tourism industry could also experience aloss of US 2.3 trillion by 2070.4Rapid decarbonization in SouthAmerica and across the globaleconomy, could both limit the worsteffects of climate change and bringan economic turning point.Reducing South America’s emissions profile willincur significant transformation costs, but if theregion starts making bold climate plays now, it canleverage existing skills and supply chain connectionsto create a path to a prosperous, low-emissionsfuture. The turning point concept demonstratesthat by choosing transition, countries and industriescould see dividends in terms of avoided costs fromclimate damage in the form of new industries andtechnologies.The upside of decarbonization could be significant.By 2030, clean energy industries could see rapidgrowth, creating new job pathways for workers fromfossil fuel–reliant industries. Mining jobs could alsoexpand as demand for critical metals, such as lithiumand copper, rise in response to increasing globalelectrification.

Key insightsBy 2045, South America could reach its criticaljuncture, achieving almost 90% decarbonizationacross the region, and preventing a future of “lockedin” warming. From this point forward, the region’s nettransition costs would start decreasing each year,moving the economy closer to a low-emissions future,thanks to growth in advanced clean manufacturingand sophisticated service-based offerings. From themid-2060s, South America would reach its turningpoint—where the economic gains of decarbonizationare greater than the costs.By 2070 the region could have 2 million more jobsthan it otherwise would in a climate-damaged,emissions-intensive world. (This is primarily drivenby avoided climate damages.) The net benefit of thetransition could grow to 1% of GDP by 2070—US 150billion—a benefit that could increase with eachsubsequent year.5

The turning point – A new economic climate in South AmericaTransforming the region’s economieswould require a significantcommitment of leadership, time,resources, and coordination.Because the region’s economies have long been tiedto carbon-intensive agriculture, land use, and fossilfuels, South America’s transformation would likelytake place over a longer timeframe than the otherregions modeled by Deloitte.3 To balance the region’seconomic development needs with decarbonization,it is vital for South American nations to start planningnow to transition to a low-emissions future.Part of this shift will require the region to adapt keyexport industries as the world shifts away from fossilfuels. Those countries and industries that are wellpositioned for the global low-carbon transition arelikely to benefit, but the modeling suggests theseshifts will pose an overall challenge to the regionaleconomy as a whole.Bold climate action in the short term will also need tobe reinforced by an enduring commitment to a lowcarbon future. With the dedication of South America’sleaders, businesses, and communities, the region cansubstantially reduce its climate risk, and transform itstransition costs into a US 150 billion annual gain thatdelivers equitable and sustainable growth.This map represents the geographical scope ofthe analysis. The discussion is presenting themacroeconomic view of inaction relative to action onclimate change for the region—the bird’s-eye view ofthe region as a whole—important regional variationin impacts and opportunities will be the subject offuture work. South America includes Brazil, Argentina,Colombia, Chile, Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, Paraguay,Uruguay, Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, FalklandIslands, and French Guiana.6FIGURE 1. South America – definition ofmodeled regionGuyanaSurinameFrench aguayChileArgentinaFalklandIslandsSource: Deloitte Economics Institute.Uruguay

Key termsThere are a number of references and terms in this report, which are defined within thiscontext as follows:Climate change: Changes in the regional and global climate brought about by increased greenhouse gas(GHG) concentrations in the atmosphere.Turning point: The economic point where the benefits of decarbonization start to offset the combinedcosts of “locked-in” climate change and the costs to transition the economy to net-zero.Net-zero emissions: A state in which GHG emissions from human activities are balanced by theemissions taken out of the atmosphere. The technical definition of this concept can be found in thetechnical appendix.Close to 1.5 C world: This pathway describes a net-zero economy by 2050 in which global averagewarming is limited to well below 2 C and as close to 1.5 C as possible, compared with preindustrial levels.Around 3 C world: An economic scenario that relates to a pathway of climate inaction, where the impliedtemperature change is 3 C above preindustrial levels toward the end of the century.Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP): A GHG concentration (not emissions) trajectoryadopted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP): A set of pathways adopted by the IPCC Sixth Assessment thatexplore how the global economy, society, and demographics might change over the next century.Clean energy and electricity: Clean electricity includes solar, wind, nuclear, hydropower, andgeothermal production technologies. Zero-emission hydrogen and bioenergy are combined with cleanelectricity to be described as clean energy.Conventional energy and electricity: Includes coal, oil, and gas as fuels and energy production as wellas their use in electricity production. Carbon capture, use, and storage is not separately modeled.7

Economics fora new climate8

Economics for a new climateNotes on the analysisAs global average temperaturescontinue to rise, climate-relateddisasters such as storms, droughts,wildfires, and floods will becomeincreasingly disruptive to businessand increasingly expensive tomitigate. Yet most economicprojections today still reflect anassumption that the economycan continue to grow the way ittraditionally has: by generatingGDP growth through carbonintensive means of production.In the face of the climate science,it’s time to consider the full costsof the emissions-intensive systemof production on the economy.In this report, the Deloitte Economics Institutepresents a new economic baseline that demonstratesthe impact unchecked climate change could haveon South America’s regional economy and itsmain industries. The analysis is based on resultsfrom Deloitte’s D.Climate model, which explicitlyaccounts for the impact of climate change on futureproductivity, economic output, and growth. (For moreinformation about the model, please refer to theaccompanying technical appendix.)While there are many uncertainties that come withmodeling a 50-year horizon, the results in this reportare not intended as an economic forecast, but ratheran analysis of two comparative scenarios, designed toanswer: “What if?”This analysis is consistent with, and reflects, the latestclimate science and incorporates leading economicmodeling techniques. Like all models, there aresimplifications. The macroeconomic analysis herelooks at the trends of change and does not focus onnonlinearities and potential climate tipping points.It is also not a model of South American politicalprocesses, nor firm-level decision-making. That said,the research provides a critical corrective to thediscourse, and can be used by leaders to make betterinformed decisions about the costs of climate inaction(Scenario A) and action (Scenario B).9

The turning point – A new economic climate in South AmericaScenario AWhatbe the economic costs of climate inactionFigure would2for South America?This economic path represents a future with a higher rate of global greenhouse gas(GHG) emissions, where there are no significant additional mitigation efforts, and theglobal average temperature increases to near 3 C by 2100. This scenario reflects a widelyadopted set of emissions, economic, and population assumptions, referred to as SSP26.0. The results of this scenario are presented as a deviation—a comparison to a world inwhich climate change didn’t exist.With this trajectory as the new baseline outlook for the region’s growth, Deloitte thenlooked at what could happen if South America—in concert with the world—decarbonizesits economy.FIGURE 2. The impact ofaccounting for climatechange on South America’sgrowth path207020502021Assumed growthGDP growth withoutaccounting forclimate damageGDP growth pathCost of climate changeSource: Deloitte Economics Institute.10Corrected growth(Scenario A)GDP growth onceclimate damage isaccounted for

Economics for a new climateScenario BWhat3 are the economic benefits of limiting global warming to closeFigureto 1.5 C for South America?The net-zero economic path depicted below reflects a sequencing of efforts—by government, business, and citizens—to achieve global net-zero emissionsby 2050. This scenario limits warming to as close to 1.5 C as possible—wellbelow 2 C. The results of this close-to-1.5 C world scenario (Scenario B) ispresented as a deviation from the 3 C world pathway (Scenario A).FIGURE 3. The opportunity ofnew economic growth undera net-zero scenario207020502021Assumed growthGDP growth withoutaccounting forclimate damageGDP growth pathNet-zero scenario(Scenario B)Economic impact ofdecarbonizationCorrected growth(Scenario A)GDP growth onceclimate damage isaccounted forSource: Deloitte Economics Institute.11

The turning point – A new economic climate in South AmericaModeling the turning point for South AmericaIn addition to demonstrating the size of the opportunity for South America, the modeling alsoidentifies the moment when the net gains from transforming to a low-emissions economy outweighthe cost to change. This net gain to the economy is what we call the turning point.The following illustration shows a rapid and coordinated path to net-zero, which begins with a periodof structural adjustment, as South America initiates an industrial and economic transformation.FIGURE 4. Modeled economicgrowth to 2070 on the path toa “close to 1.5 C world”207020602040Path ofdecarbonization(Scenario B)2025GDP growth pathTurning pointSource: DeloitteEconomics Institute.Period where investments in decarbonizationin Scenario B create temporary losses relativeto Scenario A.12Path ofinsufficientaction(Scenario A)

Economics for a new climateThe numbers included in the modeling reflectboth the costs and the benefits associated withthe transition.Costs:yThe inevitable costs—to the economy as it movesaway from emissions-intensive activity.yThe cost to the economy from global warming of atleast 1.5 C, even with strong global action to reachnet-zero by 2050.Benefits:yThe benefit of avoiding costs from limiting globalwarming, instead of reaching around a 3 Cincrease in global average temperatures.yThe benefit of a more productive and moderneconomy, where consumer demand is met andindustry preferences have changed.Modeling climate change impactsin South AmericaTo quantify its conclusions, the DeloitteEconomics Institute modeled the economicimpacts of a changing climate on long-termeconomic growth using the following process:1The model projects economic output (as measuredby GDP) with emissions reflecting a combined SharedSocioeconomic Pathway (SSP)–RepresentativeConcentration Pathway (RCP) scenario, SSP2-6.0, to theyear 2100.4 The socioeconomic pathway, SSP2, is the“middle of the road” among five broad narratives offuture socioeconomic development that are conventionalin climate change modeling. The climate scenario, RCP6.0,is an emissions pathway without significant additionalmitigation efforts (a baseline scenario).5 This results in aprojected emissions-intensive global economy.62Increased atmospheric GHGs cause average globalsurface temperatures to continue rising abovepreindustrial levels. In the SSP2-6.0 baseline scenario,global average temperatures increase more than3 C above preindustrial levels by the end of thecentury, according to the Model for the Assessment ofGreenhouse Gas Induced Climate Change (MAGICC).7(Note that present-day temperatures have already risenmore than 1.0 C above preindustrial levels.)13

The turning point – A new economic climate in South AmericaModeling climate changeimpacts in South America3Warming causes the climate to change and resultsin physical damage to the factors of production. TheDeloitte model includes six types of economic damage,regionalized to the climate, industry, and workforcestructure of each defined geography in South America.These damages capture the trend or chronic impacts ofglobal mean surface temperature increases. Deloitte’sapproach does not explicitly model individual acuteeconomic shocks driven by extreme climatic events,such as natural disasters, although these are implicitlycaptured in an increasing trend of climate changedamage.4The damage to the factors of production is distributedacross the economy, impacting GDP. Any change inemissions (and, correspondingly, temperatures) overtime results in a change to these impacts and theirinteractions. The economy impacts the climate, and theclimate impacts the economy.145The key variables of time, global average temperatures,and the nature of economic output across industrystructures combine to offer alternative baseline viewsof economic growth. Specific scenario analysis is thenconducted, referencing a baseline that includes climatechange damage. Scenarios can also include policy actionsthat either reduce or increase emissions and globalaverage temperatures relative to the current SSP2-6.0baseline view.This modeling framework involves significantresearch on climate and economic impactsacross South America, which are used as inputsfor Deloitte’s D.Climate model (refer to thetechnical appendix for more detail).

The costs ofclimate inaction15

The turning point – A new economic climate in South AmericaThe costs of climate inactionSouth America is already feeling the physical impactsof climate change, which have become even morenoticeable in recent years. Since the beginning of thepandemic, several major heat waves and droughtshave hit central South America, stretching from thePeruvian Amazon to southeastern Brazil. The flowof Paraguay River in the southern Amazon and thePantanal shrank its lowest levels in half a century, dueto severe drought. The southern Amazon experiencedits most active fire year in 2020. The Andes have nowlost the largest proportion of its ice compared to anyother mountain region in the world.Peru’s glaciersshrank by a thirdfrom 2000 to 2016.8While heat and drought have plagued some areas,others have been afflicted by flash floods andlandslides. In February 2020, Sao Paulo recorded thewettest month in 77 years, with almost double thenormal average rainfall.9 Between October 2020 andFebruary 2021, for example, almost 300 people losttheir lives in Brazil, due to flooding from historicallyhigh rainfall.16Based on existing levels of warming, climate sciencepredicts the next 50 years will bring similar extremeweather events, but they will be more intense, andthey will occur more frequently. To understand howthese types of environmental events could impactSouth America’s economy, Deloitte modeled siximpact channels, namely: heat stress, capital damage,tourism expenditure flows, lost agricultural landdue to sea level rise, agricultural yield changes, andhuman health.Climate change will harm the drivers ofeconomic growthTo demonstrate the impact climate change could haveon the economy, we incorporated regional climatedata into the following economic factors. Thesefactors would suffer climate damages in a 3 C world,which would impact future GDP growth.

The costs of climate inactionFIGURE 5. Economic impact associated with climate changeHeat stressLost labor productivityfrom extreme heatSea level riseLost productive land, bothagricultural and urbanDamaged capitalStalling productivityand investmentHuman healthIncreased incidence ofdisease and mortalityLost tourismDisrupted flow ofglobal currencyAgriculture lossReduced agriculturalyields from changingclimate patternsSource: Deloitte Economics Institute.17

The turning point – A new economic climate in South AmericaWithout sufficient global actionon climate change, South Americawould be one of the worstaffected regions in the world,10generating total economic lossesof approximately US 17 trillionin present-value terms11 by 2070.As temperatures rise, these losseswould continue to mount rapidly.South America’s key engine for growth—agriculture—is likely to struggle: By the end ofthe century, the region could lose up to 21%of its arable land due to climate change andpopulation growth.12 Growing competitivepressure for food and first-generationbioenergy exports would further exacerbateresource scarcity constraints. In a climate-damagedeconomy, productive capital and knowledge wouldbe diverted to managing health, mitigating harm, andrepairing climate damages rather than new valueadding innovations and infrastructure. This resultingreduction in productivity and lack of new investmentwould create significant losses to standards of livingand well-being. 17trillionlost from the SouthAmerican economyThese impacts would all be headwinds to growth.Over the next five decades to 2070, the region’seconomies would experience an average loss of 5%to GDP per year relative to trajectories that do notaccount for climate impacts.13 In the year 2070, aclimate-damaged South America could lose 12% ofGDP—or US 2 trillion. A loss of output at this scale isequivalent to the current economy of Brazil.14 In thissmaller, climate-damaged economy, employmentopportunities would also dwindle. In 2070 alone, therecould be nearly 18 million fewer job opportunities—almost 9% of jobs—in South America due to climaterelated damages.15Note: Present value GDP loss to 2070 dueto climate change inaction.18

The costs of climate inactionGrowth with consequencesOver the past century, South America’s economieshave benefited from a land rich with minerals, rawmaterials, and temperate climates. Capitalizing onits access to vast agricultural, oil, gas, and mineralresources, South America’s economic growth hashistorically been driven by natural resource extraction(agriculture, mining, and energy), as well as in energyintensive manufacturing.16 Major economies, such asBrazil, Argentina, Venezuela, and Chile, have been builton the success of resource-based industries and areprogressively transitioning into service-based sectors,which now make up the majority of employmentacross South America.Yet South America’s economic growth has not been asmooth journey. The boom and bust of commodityand resource-based economies can be seen in SouthAmerica’s modern economic history. Cutting throughthese ups and downs, however, is a gradual trendtoward prosperity over the past 50 years. Along withthis increased prosperity and a growing middle class,the region’s emissions-per-capita have also grown.Today, South America accounts for 6% of worldcarbon emissions.17 More than half of South America’semissions are from agriculture, land use, land usechange, and forestry (LULUCF) activities. This issignificant compared to the rest of the world, of whichless than 15% of emissions are from agricultural andLULUCF sources.18Brazil (South America’s largest economy and emitter),is currently the largest contributor of land use andland use change net carbon emissions worldwide,representing 17 to 29% of the global total.19 Home tothe world’s largest rainforest, the Amazon has played avital role as a global carbon sink. However, harvestingtimber resources and clearing for agriculturalexpansion has led to around 15% of the Amazon beingcleared since the 1970s.20 Deforestation and climatechange have now turned parts of the Amazon into acarbon source.21FIGURE 6. Trends in per capita GDP growth and emissions32.53%22%1.51%10%0.5Average annual per capita CO2emissions (tonnes)Average annual growth in GDPper capita4%0-1%1960sGDP per capita1970s1980s1990s2000s2010sEmissions tonnes per capitaNote: Per capita GDP growth to 2014, per capita emissions to 2018. Emissions data excludes LULUCF emissions.Source: Deloitte Economics Institute analysis of World Bank data.19

The turning point – A new economic climate in South AmericaSubstantial losses to industries,companies, and workersThe impacts of a changing climate will be felt across allSouth American industries, but over the next 50 years,the three industries in South America expected toincur the greatest climate-related losses are services,manufacturing, and retail and tourism. Together,these industries currently account for about 80% ofemployment in the region.In industries that rely on people power, such as theservice and manufacturing sectors, extreme heatwould decrease comfort and reduce the numberof hours in which work can be done. Difficulties intraveling and physical limits to undertaking evennormal tasks would all undermine labor productivity.Deloitte estimates that in 2070 alone, these threeindustries would experience a loss in the value addedto GDP of more than US 1.5 trillion as a result ofclimate change.The region’s burgeoning outdoor tourism sectorwould also be hit hard. From hikers climbing the peaksof Machu Picchu to families strolling the Copacabanabeach, visitors looking for outdoor adventures arelikely to be discouraged by rising temperatures, whichcould impact a wide range of adjacent businesses astourist numbers plummet. Deloitte estimates that by2070, the retail and tourism industry could experiencea loss of US 2.3 trillion in present value terms. Thiswould see more than 3 million jobs lost in 2070 alone.IndustryGDP impact 2021–2070( billion, netpresent value)Services-7,100Manufacturing-3,500In our model, the distribution of climate damagewould put South America’s transition from a naturalresource extraction economy to a services-based oneat risk. Over the next 50 years, unchecked climatechange would reduce South America’s services grossvalue added by US 7.1 trillion in net present valueterms. In the year 2070 alone, almost 9 million jobswould be displaced.Retail and tourism-2,300Construction-1,300Climate change also threatens one of South America’skey pillars of economic development, manufacturing.Extreme weather events and global pressure forlow-emission energy would reduce South America’smanufacturing GVA by US 3.5 trillion by 2070. Thisprojected loss of economic potential in this sector isequivalent to the region’s total current onventional energy-300Water and utilities-200Clean energy-100Note: Numbers may not add up due to rounding.Source: Deloitte Economics Institute.

The costs of climate inactionSocial and systemic and costsEvery region and community in South America willfeel the effects of climate change, but some willbe more adversely affected than others. Althougheconomic growth has allowed socioeconomicconditions to improve, high levels of income inequalitypersist across South America’s economies,23 andmore frequent and intense extreme weather eventsare expected to have a greater impact on thosein poverty.24 By 2030, climate change will reducethe agricultural productivity, threatening the foodsecurity of the poorest populations, particularly in thenortheast of Brazil and parts of the Andean region.25The economic risks are not just physical. SouthAmerica’s economies have worked hard to build globalprominence through the export o

From this point forward, the region's net transition costs would start decreasing each year, moving the economy closer to a low-emissions future, thanks to growth in advanced clean manufacturing and sophisticated service-based offerings. From the mid-2060s, South America would reach its turning point—where the economic gains of decarbonization