Transcription

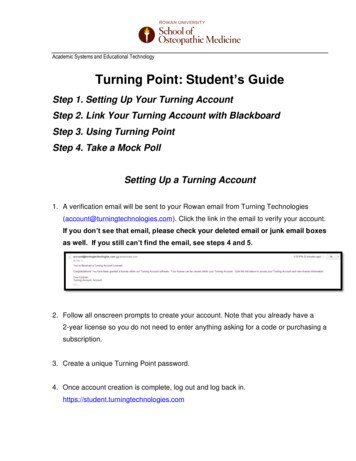

Green Climate Fund working paper No.3Tipping or turningpoint: Scaling upclimate finance inthe era of COVID-19WorkingpapersOctober 2020

All rights reservedã Green Climate FundGreen Climate Fund (GCF)Songdo International Business District175 Art Center-daeroYeonsu-gu, Incheon 22004Republic of Korea 82 34 458 6059info@gcfund.orggreenclimate.fundThe Working Paper Series is designed to stimulate discussion on recent climate change issues and related topicsfor informational purposes only.The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Green ClimateFund (GCF), including those of the GCF Board.This publication is provided without warranty of any kind, including completeness, fitness for a particular purposeand/or non-infringement. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map, andthe use of any flags, in this document do not imply any judgment on the part of GCF concerning the legal statusof any territory or any endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries.The mention of specific entities, including companies, does not necessarily imply that these have been endorsedor recommended by GCF.

Green Climate Fund working paper No.3Tipping or turningpoint: Scaling upclimate finance inthe era of COVID-19Authors of this Working Paper:Fiona Bayat-Renoux; Heleen de Coninck; Yannick Glemarec; Jean-Charles Hourcade; Kilapar?Ramakrishna; Aromar Revi.This Working Paper is part of a broader forthcoming publica:on on a science-based callto ac:on for financial decision-makers.GREEN CLIMATE FUND, OCTOBER 2020

ContentsExecutive Summary . ivIntroduction . vi1. The world has already warmed by 1.1 C exposing the financial system to unprecedentedchallenges . 12. Limiting warming to 1.5 C and adapting to climate change bring formidable investmentopportunities – but the infrastructure investment gap persists . 63. Misalignment and mistrust: Risks that undermine a ‘green’ financial system and limits toexisting responses. 104.Implications of COVID-19 on developing countries’ access to finance for climate action . 175.Maintaining climate ambition in the era of COVID-19 . 211.2.3.4.5.6.6.Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to foster policy integration . 21Develop new valuation mechanisms to accelerate asset re-pricing . 22Develop dedicated low carbon climate-resilient financial products . 23Deepen blended finance for climate change. . 24Realise the full potential of domestic financial institutions to finance the green transition. 26Innovative Financing Instruments based on global solidarity. . 28Conclusion . 30iii

Executive SummaryThe COVID-19 pandemic has brought theworld to a tipping point or a turning point inthe fight against climate change. Decisionstaken by leaders today to revive economieswill either entrench our dependence onfossil fuels or put us on a path to achievethe Paris Agreement and the SustainableDevelopment Goals (SDGs).For the COVID-19 pandemic to prove aturning point, climate action and COVID-19economic stimulus measures must bemutually supportive. Developing countriesmust be able to access long-termaffordable finance to develop andimplement green stimulus measures.Despite their potential to revive economiesin an inclusive and sustainable manner,stimulus measures in G-20 countries to datedo not prioritise green, resilientinvestments. Developing countries’ accessto climate finance is severely underminedby the COVID-19-induced economic andfinancial crises. This could take the world toa tipping point of no return in the fightagainst climate change as GHG emissionswould rebound while the financial capacityof the international community to financeclimate action in the context of COVID-19would be severely affected.Average global temperature is currentlyestimated to be 1.1 C above pre-industrialtimes. Based on existing trends, the worldcould cross the 1.5 C threshold within thenext two decades and 2 C threshold earlyduring the second half of the century.According to the Intergovernmental Panelon Climate Change (IPCC), limiting warmingto 1.5 C compared to 2 C helps preventsevere and partly irreversible consequencesfor planet, people, peace, and prosperity.Notably, physical and transition climateivrisks could impact 93 per cent of industriesand undermine the stability of economicand financial systems.The key conclusion from the IPCC is thatlimiting global warming to 1.5 C is stillnarrowly possible. An orderly transition to anet-zero carbon and resilient future couldcreate between USD 1.8 to USD 4.5 trillionin green investment opportunities annuallyover the next two decades.While there has been a steady increase inclimate finance over the past 10 years –exceeding the USD half-trillion mark for thefirst time in 2017 and 2018 – it has been tooslow to channel financial resources towardslow emission, resilient development at thescale and pace required to achieve the goalsof the Paris Agreement. As a result, theinfrastructure investment gap could reach acumulative value of between USD 14.9 andUSD 30 trillion by 2040, representingbetween 15.9 per cent and 32 per cent ofthe required infrastructure investments tofoster low emission, climate-resilientpathways.The persistent infrastructure investment gapis caused by a range of policy andregulatory, macro-economic and business,and technical risks over the projectdevelopment cycle that translate intohigher hurdle rates, deterring entrepreneursand financiers. These risks are magnified forlow emission, resilient infrastructureinvestments, particularly in developingcountries. Green investments tend to havehigher upfront capital requirements, longerpay-back periods and can have highersensitivity to policy changes and technologyrisks than conventional investments. Theseadditional and perceived risks should bebalanced against the lower operationalcosts of many green investments and thelower exposure to climate physical andtransition risks.

However, pricing climate risks is proving adaunting challenge for entrepreneurs andfinanciers alike, who are de facto asked toestimate the likelihood of various climatescenarios and their implications for physicaland transition risks at the firm and projectlevels. As a result, we are not witnessing arepricing of assets reflecting climate risks inglobal financial markets. The top 33 banksalone allocated USD 654 billion to fossil fuelfinancing in 2019. Similarly, an IMF studyfound that 2019 equity valuations acrosscountries did not reflect projectedincidence of climate physical and transitionrisks.Over the past two decades, a variety ofactions have been taken to align financewith sustainable development. To fosterclimate innovation and entrepreneurship, itincludes using scarce public resources tode-risk first-of-its kind climate investments,crowd-in private finance and create greenmarkets. To accelerate the repricing ofassets and ensure an adequate supply offinance to support climate investments, italso entails climate-related financialdisclosure, development of green standardsand taxonomies, and carbon pricing.4. Making blended finance work fornascent markets and technologiesthrough better design and bold newmechanisms;5. Deepening domestic financial sectorsand financial institutions;6. Exploring innovative financinginstruments to increase developingcountries’ access to climate financewithout increasing their sovereign debt.Together, these initiatives will help shiftfinancial flows towards a low carbon,climate-resilient future, and enabledeveloping countries to catalyse muchneeded private finance to scale up climateaction in the era of COVID-19. While wecannot ‘undo’ the tragedy of COVID-19, wecan ensure that our response to this tragedyfinances a safer and more sustainable futurefor us all.This working paper outlines six initiatives todeepen and scale up these efforts in the eraof COVID-19, namely:1. Leveraging ongoing NDC enhancementefforts to foster policy integrationbetween climate action, economicrecovery, and the SDGs;2. Developing new valuationmethodologies to support assetrepricing in global financial markets;3. Creating dedicated green and climateresilient financial products in developingcountries to access institutional finance;v

IntroductionAt a time when the effects of climatechange are already putting developmentoutcomes at risk and financing for lowemission, climate-resilient development isstill vastly inadequate, the COVID-19pandemic is creating the broadesteconomic collapse since the Second WorldWar. In response to this unprecedentedhealth and economic crisis, G20 countriesare undertaking large-scale expansionaryfiscal and monetary measures. As of thebeginning of October 2020, the totalG20 stimulus funding is estimated atUSD 12.1 trillion, roughly divided betweenbudgetary measures and liquidity support.1Developing countries on the other hand –already the most vulnerable to the impactsof climate change – do not have the samemonetary and fiscal space to roll outambitious recovery packages. The sharpdrop in public revenues, massive outflow ofportfolio capital, precipitous fall in foreigndirect investment (FDI) and remittances, andrising debt burdens have added stress togovernment balance sheets and threaten towipe out decades of socio-economic gains.Poverty may increase for first time globallyin 30 years by as much as half a billionpeople, or 8 per cent of the total humanpopulation, and income inequality is rising.2Least developed countries (LDCs) and smallisland developing states (SIDS) will be themost affected. At the same time, developingcountries have a significant opportunity toleapfrog to low carbon, climate-resilientpathways as two-thirds of theirinfrastructure investments are yet to takeplace.COVID-19 has not stopped climate change.After a temporary decline, greenhousegas (GHG) emissions in the atmosphereare heading back in the direction ofpre-pandemic levels and the world is set tosee its warmest five years on record.3However, the COVID-19 economic crisishas brought the world to either a tipping ora turning point. Economic recoverydecisions taken today will either entrenchour dependence on fossil fuels, wideninequalities and put achieving the ParisAgreement and the SustainableDevelopment Goals (SDGs) out of reach; orcreate the momentum and scale needed toshift the economic paradigm towards netzero-carbon, climate-resilient and inclusivedevelopment for all.How can the world collectively ensure thatthe COVID-19 crisis proves a turning pointto meet the goals of the Paris Agreementand the SDGs?First, climate action and COVID-19 recoverymeasures must be mutually supportive –climate action must help to reviveeconomies, and economic packagesdesigned to overcome the COVID-19 crisismust be ‘green’. Governments do not haveto compromise economic recoveryobjectives with their Paris Agreementcommitments. Many investments can meetthis dual objective. For example, investmentin energy efficient buildings can rapidlyGreenness of Stimulus Index, Vivid Economics (2020). s-for-stimulus-index/2 United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (2020). Estimates of theimpact of COVID-19 on global poverty ications/Workingpaper/PDF/wp2020-43.pdf3 World Meteorological Organization (2020). United in Science Report.https://public.wmo.int/en/resources/united in science1vi

generate large employment opportunities,reduce energy poverty, and increaseresilience to extreme weather events.Similarly, investments in climate-resilientagriculture and water management willpreserve livelihoods and foster ecosystemrestoration while investment in shovelready low emission, resilient infrastructurewill protect people, jobs, and assets.To date, the G20’s efforts to optimise themedium - and long-term contribution of itseconomic response to sustainability andresilience is uneven and limited.Stimulus measures in Western Europe,South Korea, and Canada include greeninfrastructure investments in energy andtransport. The European Union’s recoverypackage is the most environmentallyfriendly. Of the 750 billion (USD 830billion) recovery package, 37 per cent willbe directed towards green initiatives,including targeted measures to reducedependence on fossil fuels, enhance energyefficiency, and invest in preserving andrestoring natural capital. All recovery loansand grants to member states will haveattached ‘do no harm’ environmentalsafeguards.4 But overall, the G20 committedat least USD 208.73 billion supporting fossilfuel energy compared with at least USD143.02 billion supporting clean energy sincethe beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic inearly 2020.5 As the attention ofgovernments shift from immediate reliefefforts to longer-term recovery, it is criticalthat the new set of stimulus measures fostera paradigm shift toward a net-zero,resilient future.Second, developing countries must be ableto access adequate long-term, affordablefinance to develop and implement greeneconomic stimulus measures. COVID-19has exacerbated the existing ‘climatefinance paradox’, which creates a persistinginfrastructure investment gap in developingcountries. On the one hand, trillions ofdollars of savings are earning negativeinterest rates in many high-incomecountries. On the other hand, there existsbetween USD 11 to USD 23 trillion inattractive opportunities for climate-smartinvestments in emerging markets betweennow and 2030.6However, short-termism in financialmarkets and the lack of consideration ofclimate risk in investment appraisaldiscriminate against climate investments.Furthermore, compared to high emission,climate vulnerable infrastructure, green,climate-resilient infrastructure investmentstend to have high upfront capitalrequirements, long pay-back periods, astrong sensitivity to policy change, and hightechnology risks. These downsides candeter both entrepreneurs and financierswhen they are not balanced against thelower operational costs and the lowerphysical and transition risks of lowemissions and climate-resilientinfrastructure.Ensuring that every professional financialdecision takes climate change into accountis critical to foster a repricing of assets inglobal financial markets to reflect climaterisks; address the low emission, resilientinfrastructure investment gap; and ensure asustainable recovery from the COVID-19Greenness of Stimulus Index, Vivid Economics eenness-for-stimulus-index/5 https://www.energypolicytracker.org/region/g20/6 IPCC (2018)4vii

pandemic. This is the overarching privatefinance priority for COP26.7 The objectiveof this working paper is to support policymakers, the financial industry andinternational financial institutions in thiseffort. Specifically, the working paper: highlights the risks posed by climatechange to the finance system based onthe Intergovernmental Panel on ClimateChange (IPCC)’s Special Report onGlobal Warming of 1.5 C and discusseskey barriers to the re-pricing of assets inglobal financial markets; 7reviews the risks related to infrastructureinvestment and highlights ongoingUNFCCC, 2020viiiefforts to address the infrastructurefinancing gap; assesses the impact of the COVID-19pandemic on access to finance inmiddle- and low-income countries forlow emission, climate-resilientinvestments; and identifies a combination of policy,financial and institutional initiatives tosupport developing countries tomaintain climate ambition in the era ofCOVID-19.

Tipping or turning point: Scaling up climate finance in the era of COVID-191. The world hasalready warmed by1.1 C, exposing thefinancial system tounprecedentedchallengesThe climate crisis impacts people andecosystems, exacerbating inequalities andtensions. The 2015 Paris Agreement providesa framework for the global response to theclimate crisis aiming to keep averagetemperature rise this century to well below2 C and pursuing efforts to stay within 1.5 C.In its Special Report on Global Warming of1.5 C (SR1.5), the IPCC concluded thatlimiting warming to 1.5 C compared to 2 Chelps prevent severe and partly irreversibleconsequences. Impacts at 2 C of warmingwould push hundreds of millions of peopleinto poverty; put over 330 million people atrisk of food insecurity and 590 million at riskof water insecurity; expose over 350 millionin mega-cities to heatwaves; and lead to thecomplete extinction of warm-water coralsand a sea ice-free Arctic at least once everydecade. Furthermore, while in 2019 theworld had already warmed by 1.1 Ccompared to pre-industrial times, theannounced contributions made by Parties tothe Paris Agreement are projected to lead toa warming of around 3 C if fullyimplemented and to even highertemperatures if these commitments are onlypartially fulfilled. This would increase thepace of climate impacts and reduce theeffectiveness of adaptation efforts.The climate crisis also undermines thestability of national and global economic and8financial systems. Financial assets andinvestments are exposed to physical andtransition climate risks. Physical risks, whichstem from the physical impact of climatechange, include both acute risks – from anincrease in the frequency and severity ofextreme weather events (e.g. more intensedroughts, greater floods, more severecyclones, etc.); as well as chronic risks –from slow-onset events (e.g. polarward shiftof ecosystems, sea level rise, human diseasemigration, etc.). Transition risks, which occurdue to structural changes arising from theshift to a low carbon, climate-resilienteconomy, can involve technologicalinnovations (e.g. breakthrough in battery orhydrogen technology), changes in legislationand regulation (e.g. ban of high emissionproducts, rapid implementation of a carbontax following a catastrophic weather event orelectoral change), and changes in consumerbehaviour (e.g. a shift in attitudes towardsthe purchase of diesel cars, air travel ordeforestation-based products).Climate risks will have major implications formost sectors of our economies. They impactrevenues, cash flows and operating costs,asset values and financing costs of firms andfinancial institutions.8 The physical effects ofclimate risk tend to impact industries withphysical assets in risk-prone areas (e.g., realestate in coastal or wildfire-prone areas),industries where infrastructure resiliency andbusiness continuity are societal necessities(e.g., health care delivery,telecommunications, internet, utilities), andindustries dependent on natural capital (e.g.,those that rely on productive land andavailability of water, such as agriculture,meat, poultry, and dairy). Financialinstitutions, especially insurance companiesand smaller regional and local banks, are alsoSustainability Accounting Standard Board (2016): Climate Risk-Technical Bulletin1

GCF WORKING PAPER SERIES NO. 3vulnerable to claims and loan default lossesfrom chronic and acute physical risks.9Risks related to the transition tolow-emission, resilient developmentpathways tend to have material impactson producers of energy (fossil fuelcompanies, renewable energy companies),manufacturers and providers ofenergy-consuming products and services,energy- and/or water-intensive industries,and nature-based products and serviceproviders. Stranded capital from fossil fuelassets alone suggests a potential global lossof wealth between USD 1 trillion and USD 4trillion.10 Similarly, sales ofdiesel-based cars within the Europeanmarket could shrink from 52 per cent to9 per cent by 2030.11Overall, physical and transition risks couldimpact 72 out of 79 industries assessed bythe Sustainability Accounting StandardBoard.12 This equates to USD 27.5 trillion,or 93 per cent of equities by marketcapitalisation in the US alone, and representsa systematic risk to the stability of thefinancial system and security of societies.Diversification does not eliminate climaterisks. As a result, investors need tounderstand and adequately price theirclimate-risk exposure.How well the transition towards climatestabilisation is managed, in terms of speedand quality, will strongly affect thedistribution of physical and transition risksfor the financial system across industriesand over time. Through a self-reinforcingfeedback loop (Figure 1), any rise in globaltemperatures can trigger a damagingchain reaction, affecting societal healthand security.Managing climate risk in the US financial system (2020).Mercure, et al, (2018)11 Frost and Guillaume (2016)12 The seven industries for which SASB standards include no climate- related topics are: Consumer Finance,Education, Professional Services, Advertising & Marketing, Media Production & Distribution, Tobacco, andToys & Sporting Goods.9102

Tipping or turning point: Scaling up climate finance in the era of COVID-19FIGURE 1. FEEDBACK LOOP THAT CAN MAKE CLIMATE CHANGE A THREAT TO FINANCIAL STABILITY13A clear conclusion from the IPCC SpecialReport is that limiting warming to 1.5 C andadapting to the impacts of climate changerequire accelerating the transition acrossfour systems: energy, land and ecosystems,urban and infrastructure, and industry.System transitions are associated withfinancial risk, but so is waiting for climatechange impacts to kick in. Modelling studiesindicate that to limit warming to 1.5 C,global CO2 emissions need to be halved by2030 and reach net-zero by 2050. CO2 alsoneeds to be removed from the atmosphereat a significant scale during the second halfof the 21st century. Different futurepathways are still possible within the remitof the Paris Agreement and these have verydifferent implications for sustainabledevelopment and the financial system(Figure 2). For instance, the P1 pathwayneeds finance for afforestation, as well as13changes in societal systems that somewould call disruptive, digitalisation,and other technologies that enabledemand-side emissions reductions. At theother end of the spectrum, P4 requiresmuch higher volumes of finance invested inadvanced technologies for carbon dioxideremoval (CDR), like bioenergy with carboncapture and storage.Hence acting sooner to enact systemtransitions is vital to limit the physical risksof climate change. Immediate action canalso contribute to economic recoveryfrom the COVID-19 pandemic and toachievement of the SDGs by 2030.Conversely, delaying the transition willincrease physical risks without realizing thedevelopment co-benefits, and result in adisorderly transition, with greater costs andfinancial losses.Based on NGFS, 2019.3

GCF WORKING PAPER SERIES NO. 3According to the IPCC, accelerating systemtransitions and limiting global warming to1.5 C are still narrowly possible if a large setof enabling conditions is established. Asdiscussed in the following sections, theseinclude carbon pricing and largeinternational financial transfers to accountfor the conditions of the transition indifferent socio-economic contexts.However, dedicated efforts will be neededin the era of COVID-19 to ensure thatdeveloping countries can access long term,affordable finance to realise their climateambitions.FIGURE 2: RISK CHARACTERISTICS OF FOUR ILLUSTRATIVE PATHWAYS PURSUING DIFFERENT STRATEGIESTO LIMIT WARMING TO 1.5 C 14144P1P2P3P4StorylineSocial, business andtechnological innova8ons;lower energy demand by2050; higher livingstandards (also in theglobal South); downsizedenergy system; rapiddecarbonisa8on of energysupply; afforesta8on theonly CDR op8onconsidered; no CCS.Focus on sustainability incl.energy intensity; humandevelopment; economicconvergence; interna8onalcoopera8on; shiKs towardssustainable and healthyconsump8on paLerns;low-carbon technologyinnova8on; well-managedland systems; limitedBECCS.Societal and technologicaldevelopment followhistorical paLerns;emissions reduc8onsthrough changingproduc8on of energy andcommodi8es rather thanthrough reduc8ons indemand.Economic growth andglobalisa8on; greenhousegas-intensive lifestyles,including high demand fortransporta8on fuels andlivestock products;emissions reduc8onsmainly throughtechnological means; CCSand BECCS.Temperatureoutcome (within0.1 C accuracy,medianestimate)Warming limited to 1.5 CWarming limited to 1.5 CWarming limited to 1.6 CWarming exceeds 1.5 Climit by 20 per cent (0.3 C)with assump8on it can bereversed by 2100Risk ofovershoot of1.5 CSmallSmallLargeVery large (designed tofirst miss the target)As shown in Figure SPM.3b of the IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 C (IPCC, 2018). Darker cellcolours indicate higher risk. AFOLU Agriculture, Forests and Other Land Use, BECCS bioenergy and carbondioxide capture and storage.

Tipping or turning point: Scaling up climate finance in the era of COVID-19Alignment withsustainabledevelopmentVery strongStrongMedium, with poten8altrade-offsWeak, with marked tradeoffsPhysical climaterisks to 2050LowestLowMediumHighestPhysical climaterisks after 2050*LowLowestLowHighTransition risks & OpportunitiesEnergy demandreduction/managementVery highHighMediumLowEnergy hestAsset strandingNear-term re8rement offossil-fuel assetsNear-term re8rement offossil-fuel assetsModerate stranding offossil-fuel assetsStranding delayed by adecade but then withhigher magnitude**Reliance on CDRSmallMediumLargeExtremeDeployment ofland-basedmitigation emeFailure to achieve demandand behavioural changesmay leave liLle 8me toramp up supply-sidemeasures like CCS.Full por\olio of supply anddemand op8ons hedgesagainst failures anddiscon8nua8on risksFailure to address poten8altrade-offs from land-basedmi8ga8on, risks policiesbeing reversed due tosocietal concerns.High risk of necessary post2030 climate policiesstrongly compe8ng withother societal concernsand hence not beingimplemented ordiscon8nued.5

GCF WORKING PAPER SERIES NO. 32. Limiting warming to1.5 C and adapting toclimate change bringformidable investmentopportunities –but the infrastructureinvestment gap persistsAchieving net-zero emission by 2050requires transitions across four systems.These transitions involve the deployment ofa range of technologies and practiceswithin the next few decades, with some ofthem still to be developed. Adapting to theconsequences of 1.5 C global warming alsorequires considerable investments in watermanagement, flood protection, newagricultural systems, health systems andnew architectures. The warmer the planet,the greater the adaptation needs, forinstance, because of sea level rise or morefrequent heat waves. Specific adaptationinvestments are projected to be in the orderof between USD 140 to USD 300 billionannually by 2030.15However, a critical part of enhancingadaptive capacities of societies will comefrom reducing the infrastructure investmentgap in basic goods and services, whichdetermine progress made towards theSDGs. Studies indicate that the totalinvestment requirements for SDGs and theParis Agreement could be reduced by40 per cent by a high level of integration ofclimate and SDG policies.16Most estimates of the investmentopportunity related to climate changemitigation, including those in the SR1.5,cover energy supply and energy savings.Available studies, however, show thatincluding transport and the builtenvironment leads to three times higherinvestment opportunities and would reachbetween USD 1.8 to USD 4.5 trillion annuallyover the next two decades.17 Despite thisrange of uncertainty, the incrementalinvestments in energy, transportation andbuildings needed to achieve an emissionpathway compatible with 1.5 C require theredirection of 2.5 per cent of the globalfixed capital formation (GFCF) towards lowemission options.18While this relatively modest figure suggeststhat this goal should be attainable, andwhile estimates show significant increasesin low-emission investments andsustainable investments over the pastdecade, the infrastructure investment gapcould reach a cumulative value of betweenUSD 14.9 and USD 30 trillion by 2040. Thisrepresents between 15.9 per cent and32 per cent of the required infrastructureinvestments to foster low emission,climate-resilient pathways.19The growth in climate finance (amountingto over USD half-trillion for the first time in2017 and 2018)20 is insufficient and growingtoo slowly to channel financial resourcestowards low emission, sustainabledevelopment at the scale and pace requiredto achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement.Climate finance refers to local, national orUNEP (2016). Climate Change Adaptation Finance Gap ReportRozenberg and Fay (2019)17 Rozenberg and Fay (2019)18 IPCC (2018)19 Arezki, R., P. Bolton, S. Peters, F. Samama, J. Stiglitz (2017)20 USD 612 billion in 2017, USD 546 billion in 2018 (CPI, 2019)15166

Tipping or turning point: Scaling up climate finan

world to a tipping point or a turning point in the fight against climate change. Decisions taken by leaders today to revive economies will either entrench our dependence on fossil fuels or put us on a path to achieve the Paris Agreement and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). For the COVID-19 pandemic to prove a