Transcription

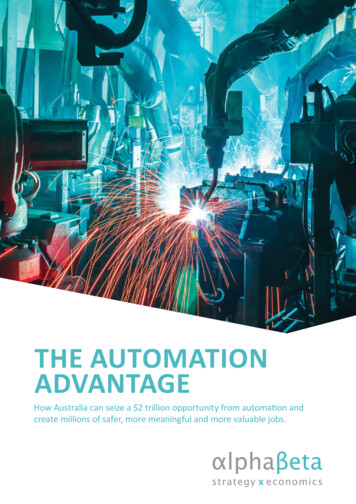

THE AUTOMATIONADVANTAGEHow Australia can seize a 2 trillion opportunity from automation andcreate millions of safer, more meaningful and more valuable jobs.

This report was commissioned by Google and prepared by AlphaBeta. The information contained inthe report has been obtained from third-party sources and proprietary research.All monetary figures reported are in 2015 real Australian dollar terms, unless otherwise indicated.AlphaBeta is a strategy and economic advisory business serving clients across Australiaand Asia from offices in Singapore and Sydney.SydneyLevel 7, 4 Martin PlaceSydney, NSW, 2000, AustraliaTel: 61 2 9221 5612Sydney@alphabeta.com2SingaporeLevel 4, 1 Upper Circular RoadSingapore, 058400Tel: 65 6443 6480Singapore@alphabeta.com

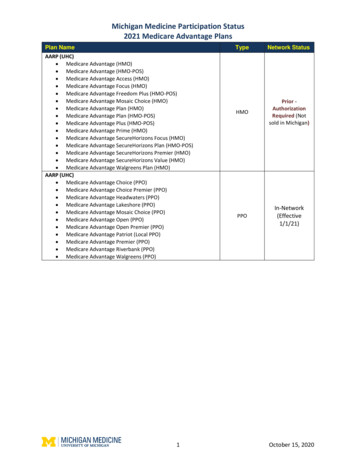

Automation is changingthe way we workMachines willunburden theaverage Australian of2 HOURSof the most tediousand manual work a weekover the next 15 yearsAutomation could deliver a 2.2boost to Australia’s nationalincome between 2015 and2030 from productivity gainsTRILLION 1 1.2TRILLIONTRILLIONfrom accelerating therate of automationfrom transitioning theworkforceAs automation reduces routine and manual work, our jobs will become.SAFERMORESATISFYINGMOREVALUABLEWorkplace injurieswill fall by 11% asdangerous manualtasks are automated62% of low-skilledworkers willexperience improvedsatisfactionWages for nonautomatable work are20% higher than forautomatable workAustralia currently lags global leaders in Automation50%fewer Australian firms areengaged in automation comparedto leading countries

4

CONTENTSEXECUTIVE SUMMARY61AUTOMATION IS CHANGING THE WAY AUSTRALIANS WORK91.1Over the next 15 years, the average Australian worker will spend 2hours per week less on manual and routine tasks111.2Automation will change the jobs we do, but it will mostly change theway we do our jobs122AUTOMATION IS A 2.2 TRILLION OPPORTUNITY FORAUSTRALIA—IF WE GET IT RIGHT152.1Australia would gain 1.2 trillion from transitioning workers affectedby automation162.2Australia would gain 1 trillion by accelerating the rate of automation193AUTOMATION WILL MAKE AUSTRALIAN JOBS SAFER, MORESATISFYING AND MORE VALUABLE213.1Jobs will become safer, as machines take over the most dangeroustasks at work213.2Jobs will become more satisfying, as machines take over the mostroutine tasks at work223.3Jobs will become more valuable, as machines take over the leastproductive tasks in the economy234HOW AUTOMATION CAN BECOME A SUCCESS STORY INAUSTRALIA254.1Policy should be tailored for different groups affected by automation254.2Lessons from abroad: how other countries are responding toautomation315APPENDICES345.1Appendix A: Estimating timeshares of tasks in the economy345.2Appendix B: The impact of automation on work quality365.3Appendix C: Evaluating the potential gains from automation405.4Appendix D: Evaluating the impact of automation for different groupsof workers425

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYTechnological change has long been asource of anxiety for workers. Today,improvements in communicationtechnology, robotics, and machineintelligence are rekindling age-old concernsthat technology will soon force millions ofpeople out of work. This report providesa fresh perspective. Automation is, at itscore, an opportunity to harness the powerof machines to improve human lives.Over the long term,automation technologieswill be the primary engineof prosperity, lifting wages,living standards and workconditions. But in theshort term, these sametechnologies present risksthat must be managed.6If we get it right, automation could significantly boostAustralia’s productivity and national income—potentiallyadding up to 2.2 trillion Australian dollars in value to oureconomy by 2030.But this opportunity will not land in Australia’s lap. To unlockthe benefits of automation we must be bold enough to leadchanges. This means embracing technology’s potential tomake our workplaces more productive, while taking steps toprevent Australia’s most vulnerable workers from sliding intounemployment. This report outlines how Australia can turnthe trend of automation into a national economic success story.To understand the impact of automation on Australia’seconomy this report analyses how automation changesthe working life of every Australian. The use of machinesis changing what jobs we do. Strenuous physical jobs aredisappearing on factory floors, and routine administrativejobs can increasingly be done without human workers. On theflipside, more jobs are being created in community, personaland business services, and other specialised professions thatrely on uniquely human skills such as thinking creatively andbeing able to understand other people’s emotions.However, more than changing what jobs we do, automationis changing the way we do our jobs. This report gives acomprehensive picture of the impact of automation onAustralian workers by digging below the job level andanalysing how technology is affecting the time that we spendon different work tasks within our jobs. In detail: every oneof the 20 billion hours that Australians worked last year wasassigned to one of more than 2,000 work tasks, creating acomplete picture of how much time Australians have spent oneach work task over a 15-year period.The results provide remarkable insights and allow us tounderstand likely future work patterns. Technology is alreadychanging the nature of human job tasks. For example, retailworkers are spending less time ringing up items at the registerand more time helping customers; bank employees arespending less time counting banknotes and more time givingfinancial advice; teachers are spending less time recordingtest scores and more time assisting students; factory workersare spending less time on the assembly line and more timeoptimising production and training other workers.

Over the past 15 years alone, Australians have reduced theamount of time spent on physical and routine tasks by 2 hourseach week. Most of that change isn’t coming from the lossof physical and routine jobs. Rather, it comes from workersswitching to different tasks within the same jobs, as machinestake over an increasing load of the repetitive routine work.Automation isn’t a force we can stop. But Australia’s economyhas a lot to gain if we manage to avert the employment risksthat come with growing machine use. To unlock the fullamount of gains, two conditions need to be fulfilled:First, Australia requires a strong policy framework to ensureworkers at risk of being displaced are redeployed. There isno reason why this should not be the case. History shows thatpast waves of technological disruption have ultimately ledto increased prosperity, productivity and employment. Overcenturies, machines have progressively replaced labour inagriculture, manufacturing, administration and professionalservices. Yet, humans always find work to do—partly becausetechnology creates new opportunities for workers and partlybecause humans are infinitely capable of redefining what wemean by work. Today, there is a myriad of occupations thatno one ever heard of a few decades ago: think of social mediamanager, software engineer, ride share driver, well-beingcoach, website builder or Zumba instructor. In response tothe claim that ‘robots will take all our jobs’, economist MiltonFriedman noted that “human wants and needs are infinite,and so there will always be new industries, there will alwaysbe new professions.” Centuries of economic progress confirmthis view.This is not to say automation cannot cause unemployment,especially for older and vulnerable workers who lose theirjobs and are unable to find a new one quickly. If automationin Australia proceeds at its historical pace, it will deliver asignificant economic dividend of around 1.2 trillion over thenext 15 years, but this gain is entirely predicated on our abilityto redeploy the workers that are displaced by machines intonew forms of work.7

As machines take overour most dangerous,most tedious and leastvaluable tasks, human workwill become more human.Second, Australia must encourage more firms to intensifytheir automation efforts. Currently, Australian companies arebehind leading global peers in embracing automation. Only 9per cent of Australia’s listed companies are making sustainedinvestments in automation, compared with more than 20 percent in the United States and nearly 14 per cent in leadingautomation nations globally. This low rate of investmentin automation technology acts as a handbrake on ourproductivity growth that will ultimately reduce our nationalincome. If Australia accelerated its automation uptake, itwould stand to gain up to another 1 trillion over the next15 years.Both scenarios together—successfully moving all workersaffected by automation into new employment ( 1.2 trillion)and accelerating the rate of automation ( 1 trillion)—represent a 2.2 trillion opportunity for Australia by 2030.This economic dividend, however large, is only part of thebenefit that automation can bring to Australia. Perhapsmost importantly, automation has the potential to improvethe work lives of every single Australian in a very tangibleway. This report shows that the tasks lost to automation aretypically the most dangerous, least enjoyable and the leastlikely to be associated with high pay. As automation shiftsthese dangerous, tedious and less valuable tasks from peopleto machines, work injuries are set to fall and work satisfactionlevels bound to rise as workers can focus on more creativeand interpersonal activities. Automation will make worksafer, more meaningful and more valuable. In other words:machines will make human work more “human”.8What is automation?In this report we define automation as the process ofusing machines to perform tasks that would otherwisebe done by humans. These can be physical, such as acombine harvester collecting grain so that the workdoes not have to be done by hand, or analytical, suchas a 'spell checker' proofreading and finding errors ina document instead of a person. Automation coversbroad range of technologies including advances inArtificial Intelligence (AI), robotics, and the Internetof Things (IoT).

1AUTOMATION IS CHANGINGTHE WAY AUSTRALIANS WORKAutomation is causing Australian workers to rely more on their brains and personalitiesthan on physical labour. By 2030, machines will likely take over 2 hours of our mostrepetitive manual job tasks per week.This report looks at the impact of automation on Australianwork. It goes beyond a mere analysis of how automation ischanging what jobs we do. Rather, it investigates the wayautomation is changing how we do those jobs. It analyseshow the use of machines shifts the amount of time spent ondifferent work tasks. For example, anyone who has walked intoa bank branch in the last 20 years can see that automation hashad a transformative effect. For one thing, there are far fewertellers standing behind the counter. Automation, throughthe rise of automatic teller machines (ATMs) and morerecently through the growth of online and mobile banking,has reduced the need for staff to dispense cash and processroutine transactions.But the replacement of administrative staff with automatedprocesses doesn’t tell the full picture of how the workinglives of bank employees have changed. Banks still have tensof thousands of workers in branches across the country, butinstead of calling them “tellers”, these people are now oftencalled “service consultants”. They spend far less time, if any,counting notes and far more time engaging with customers,such as providing complex advice on financial planning orhome loans.To understand the full impact of automation on the wayAustralians work, we have to dig beneath the occupationallevel of Australia’s 12 million workers to understand not justwhat jobs they do, but how they spend their time at work.This report analyses how Australians spend a total of 20 billionwork hours each year, assigning each of those hours to one ofmore than 2,000 different work tasks and then bundling theseinto six “task groups” (see Box 1 for methodology): Interpersonal tasks: These tasks primarily involve directlyengaging with other people. A shop assistant sellingproducts to customers would be a typical interpersonaltask, as well as a manager training staff or a teacher helpingstudents solve a complex maths question. Creative & decision-making tasks: These tasks involve a largeamount of creativity and out-of-the-box thinking. Typicalexamples include a painter creating an artwork, a softwaredeveloper writing a new computer program, and a managerconsidering a firm’s future strategic direction. Information synthesis: These tasks require workers tointerpret information or extract meaning from simple datapoints. An analyst making sense of an industry trend andwriting a commentary to provide context around this trendwould be a typical example. Information analysis: These tasks involve gathering andprocessing of information. Typical examples include ameteorologist measuring rainfall, or a cashier calculatingdaily sales values. Predictable physical tasks: These tasks include repetitiveand routine physical work, such as assembly line workerspackaging equipment, or agricultural workers picking fruit. Unpredictable physical tasks: These tasks consist of a widerarray of physical work that is not happening on a routinebasis. A car mechanic repairing different types of defectsundertakes a physical, yet unpredictable task. The sameapplies to a doctor performing various types of surgery.Activities in the first three tasks groups—interpersonal,creative & decision-making, and information synthesis—aregenerally the least likely to be rapidly replaced by machines.However, activities in the last three tasks groups—informationanalysis, predictable physical and unpredictable physical—are expected to experience workplace change driven byautomation in the near future.9

BOX 1Methodology: Understanding the tasks undertaken in every Australian jobThis report analyses how people from all walks of life—teachers and tradesmen, computer programmers and priests—have been spending their time at work since the year 2000. The observed historical trends are then used to drawconclusions on likely work patterns until 2030.We use a detailed occupational database (O*NET) which breaks down every job into more than 2,000 activities.1 Thedatabase reports the frequency with which each activity is performed in an occupation. Activities and frequencies werefitted to match the total weekly work hours for each occupation to evaluate the amount of time spent on each activity(see Appendix A).This approach has two significant benefits over approaches which use judgement or survey data to analyse the timespent on tasks. The first advantage is that this approach removes human error from the equation; human judgement isoften subject to biases and crowding effects as can be seen from notable failed “predictions” from the past.The second advantage is that the approach is repeatable over time: whilst surveys can’t be conducted in the past, theapproach used in this report can be taken to historical data. This methodology can thus be used to discover and interprethistorical trends that surveys cannot measure.EXHIBIT 1The impact of automation is best understood by breaking theeconomy down into “tasks”350 “Occupations”Non-exhaustive examples:Salesassistant2000 “Activities”6 “Task groups”Non-exhaustive examples:Review documentsInterpersonalAssess productsAssist customersCreative &decision-makingOperate equipmentFactoryworkerMonitor facilitiesPerform manual tasksAssist studentsManagerEvaluate processesSupervise othersDesign lesson plansTeacherMaintain hardwareMonitor environmentDifficult SOURCE: O*NET, AlphaBeta analysis1. The US government’s occupational data base O*NET contains detailed information on more than 2,000 work-related activities in almost 1,000 US occupations.10

AUTOMATION IS CHANGING THE WAY AUSTRALIANS WORK1.1 OVER THE NEXT 15 YEARS, THE AVERAGEAUSTRALIAN WORKER WILL SPEND 2 HOURS PERWEEK LESS ON MANUAL AND ROUTINE TASKSBy analysing all the hours Australians workers allocate acrossmore than 2,000 tasks, we get a remarkable picture of howthe real working lives of Australians have been changing overthe last 15 years.The results of the analysis, summarised in Exhibit 2, paint thepicture of a workforce that is changing rapidly. Automationis causing Australian workers to rely on their brains andpersonalities more than physical labour. Workers have beenable to spend less time on routine and manual tasks andmore time on complex activities that require a high degreeof creative thinking, decision-making, problem-solving,interpretation of information, and personal interaction.EXHIBIT 2Automation is changing the way we work, reducing the amount oftime a worker will spend on routine tasks by up to 2 hours a weekChange in types of tasks performed by Australian workersAverage share of time spent on work activityInterpersonalCreative &decision-making31%Predictablephysical39% 1 hour 20minutes2 additional hours aweek spent on nonautomatable predictablephysical35%2015-2030 change inaverage work week26%27% 20 minutes7% 20 minutes-20 minutes4%8%6%7%14%11%6%9%-50 minutes-50 minutes18%16%13%2000201520302 fewer hours a weekspent on automatabletasks.SOURCE: O*NET, AlphaBeta analysis11

In 2000, automatable activities—a baker cleaning his trays, awarehouse worker driving a forklift, a doctor sifting throughpiles of scanned images to detect a tumour—used to take up14 hours (40 per cent) of a typical 35-hour week. Since then,the share of automatable tasks has declined to 11.9 hours (34per cent) per week in 2015.On the flipside, Australian workers have begun to fill their dayswith a growing number of tasks that require interpersonalskills. For example, they are spending more time talkingto patients, negotiating with clients or conferencing withcolleagues. The relevance of these social interactions at workhas risen steadily from consuming 10.9 hours (31 per cent) ofa typical 35-hour week in 2000 to 12.2 hours (35 per cent) perweek in 2015.Exhibit 2 also shows a forecast for what new work Australianswill carry out over the next 15 years. This forecast is basedpurely on the historical trend (note that in a later section,we discuss the implication of this trend accelerating). In thisscenario, it is estimated that the average Australian will useanother 1 hour and 20 minutes of work time for job-relatedactivities involving interpersonal skills by 2030, leading theirtotal share to rise to 13.7 hours (39 per cent) per week. Tasksrequiring creative and complex cognitive thinking will alsobecome more important. In all, Australians will spend onaverage 2 hours per week more on interpersonal, creative andsynthesis tasks; and less time on routine and manual tasks.121.2 AUTOMATION WILL CHANGE THE JOBS WEDO, BUT IT WILL MOSTLY CHANGE THE WAY WEDO OUR JOBSMost of the media commentary on automation focuses on theimpact at a jobs level—on jobs destroyed or created. This isonly a part of the picture. Exhibit 2 shows that machines areexpected to take over an additional 2 hours of routine andmanual work in an average Australian work week by 2030. Butmost of this change won’t come from people changing jobsas manual and routine work disappears. In fact, 71 per centor 1 hour and 25 minutes, of the total expected reductionin work time will come from people doing the same job,but completing fewer manual and routine tasks on the job(Exhibit 3).Only 29 per cent of the automation driven workplace changewill involve workers changing jobs. Whilst these workers are atrisk of unemployment, it is important to understand that thisdoes not imply all workers at risk will lose their jobs. Further,automation is likely to create new jobs for displaced workers.For example, technological change often drives workplaceinnovation: the rise of facebook, twitter, instagram and othersocial networks led to the creation of 'social media managers'.

AUTOMATION IS CHANGING THE WAY AUSTRALIANS WORKEXHIBIT 3Over two-thirds of the shift away from automatable tasks will bedriven by people changing the way they work, not changing jobsImpact of automation on Australian workExpected fall in average weekly work time spent on automatable tasks from 2015-2030Reduction due tomoving jobs35mins(29%)1hr 25minsLess than one-third of the 2-hourfall in automatable work perperson will be due to workersmoving between jobs.(71%)Reduction due to changingtasks within jobsMore than two-thirds of the 2-hour fall inautomatable work per person will be dueto workers remaining in their jobs, butchanging tasksSOURCE: O*NET, ABS, AlphaBeta analysisA detailed analysis of how Australian workers have beenspending their time in recent years, as seen in Exhibit 4,reveals a substantial shift away from monotonous tasks.Between 2000 and 2015, the average Australian full-timesalesperson has spent 9 hours per week less on scanningbarcodes and other automatable tasks and instead used thattime to assist customers. Similarly, new online educationprograms and interactive learning software are freeing upteachers to spend more time interacting with their students.Since 2000, an average Australian full-time teacher has beenable to delegate 8 hours of dull weekly routine work—such asrecording test scores—to computers. Occupational data showthat teachers have used the newly gained spare time for tasksrequiring creativity, interpersonal skills and strategic problemsolving abilities, such as helping special-needs students.13

The roles of employees in the manufacturing sector, by farthe biggest user of automation technology according to theInternational Federation of Robotics, are rapidly changing.2 Asindustrial robots and other process-automation technologiesare increasingly shouldering the physical part of factory work,labourers doing routine manual work, such as packers orassembly-line workers, have spent eight hours more per fulltime work week on training and other non-automatable tasksbetween 2000 and 2015.Even managers, which are commonly thought of as beingimmune to the impact of automation, have gained one hourof work time per week since 2000 to spend on non-routineactivities thanks to technology. New management automationsoftware helps them collect huge amounts of complex dataand speed up office workflows, allowing them to focus moreon creative and interpersonal tasks, such as strategic planningand keeping customers and staff happy.EXHIBIT 4Automation will free up time for workers to focus on higher-value tasksNon-exhaustive examples:Task composition of workFull-time hours per weekAutomatable200028Time saved on automatable tasksReduction in weekly hours spent on automatable tasksNon-Automatable201537Salesassistant9 hourchange12 Less time scanning items More time assisting customers36 14Factoryworker8 hourchange34263536Manager1542735Teacher213 Less time on an assembly line More time training other workers1 hourchange Less time collecting data8 hourchange Less time recording test scores More time on strategic planning More time assisting special-needs students5Notes: Assumes a full-time worker works 40 hours per week, figures rounded to nearest hour1 Unweighted average of ANSZSCO 1 digit code used to estimate manager timeshares (excluding farmers and CEOs)2 Example based on high-school teacherSOURCE: ABS, O*NET, AlphaBeta analysis2 International Federation of Robotics (2016), World Robotics Report 2016.14

2AUTOMATION IS A 2.2 TRILLIONOPPORTUNITY FOR AUSTRALIA—IF WE GET IT RIGHTAustralian firms adopt automation technologies at less than half the rate of Swiss andAmerican firms. This is a missed opportunity. Accelerating the pace of automation couldboost our productivity and economic growth, provided workers remain in employment.The growing use of machines presents a substantialopportunity for the Australian economy. The previous sectionspelled out the nature of that opportunity in the simplestterms: at the current rate of automation, the averageAustralian worker will need 2 hours less each week to do theirjob by 2030 because machines will liberate them from a rangeof automatable tasks. Automation is quintessentially a positiveproductivity shock.This section quantifies the opportunity for Australia tocapitalise on this positive productivity shock and turn thegrowing trend to automation into a national economic successstory (Exhibit 5).First, there is an immense potential gain from having stronglabour-market and education policies in place to ensure thatwork hours displaced by machines are reinvested in otherwork or new employment for the minority of displacedworkers. To put this in numerical terms: if every Australianwas able to spend the extra 2 hours of weekly work time thatmachines are expected to shoulder over the next 15 years onhigher-value activities (rather than simply reduce their worktime by 2 hours per week), it could boost Australia’s economyby up to 1.2 trillion in value over that timeframe.3EXHIBIT 5Automation could deliver a 2.2 trillion dividend to Australia if workers aretransitioned successfully and the uptake of automation is acceleratedIncremental gains from automationNet present value of GDP increment, trillion 1.0 2.2 1.2Gains from transitioning workersScenario:Difference in value betweenautomation displacing workers vsworkers transitioned to new activitiesGains from accelerating automationTotalDifference in value between maintaininghistorical rate of automation, andcatching up to US rate.Sum of transition and acceleration3. Measured in Net Present Value (NPV) terms.15

EXHIBIT 6The rate of automation today is no higher than previous peaks over the last50 years, but the industries impacted have changedJob losses due to productivity improvement by sector% of employment lost each year, US itiesServices0.8Historical job losses have beenconcentrated in highly physicalindustries such as agricultureand manufacturing0.70.6Service industries have beenless impacted throughouthistory, but this is beginningto 85199019952000200520102015Note: 2011 onwards based on the linear trend for each industry since 1990SOURCE: Groningen Growth and development Centre. World-KLEMS databaseSecond, there is significant scope to increase the gains fromautomation if Australian firms deepened their investmentsin productivity-enhancing technologies. If historical trendscontinue, automation will improve Australia’s labourproductivity by 8 per cent over the next 15 years. Thismeans automation would drive around one third of thetotal expected increase in labour productivity in Australia by2030.4 But Australian companies lag behind global peers inembracing automation. If Australian firms were to acceleratetheir automation investments to match leading countriessuch as the US, they could add around 1 trillion to Australia’seconomic output over the next 15 years.52.1 AUSTRALIA WOULD GAIN 1.2 TRILLIONFROM TRANSITIONING WORKERS AFFECTED BYAUTOMATIONFor Australia to make automation an economic success,we must ensure that the labour freed up by machines isredeployed, not left idle. For the most part, workers will beable to easily adjust their work routine and remain in theircurrent jobs. However in some instances automation can leadto higher unemployment or reduced work hours. If overallemployment is reduced, rather than output increased, thenthe potential economic gains of automation could evaporate.4. Labour productivity measured as real GDP per hour worked was 84 in 2015 and is expected to rise to 103 by 2030, 7 of the change can be attributed toautomation based on historical trends with the remaining change due to all other factors (see Appendix C).5. Measured in NPV terms.16

AUTOMATION IS A 2.2 TRILLION OPPORTUNITY FOR AUSTRALIA—IF WE GET IT RIGHTHistory suggests that there is no reason for automation tospark widespread and persistent unemployment. Past wavesof technological disruption have ultimately led to increasedprosperity, productivity and employment. Over centuries,machines have progressively replaced labour in agriculture,manufacturing, administration and professional serviceswithout causing mass unemployment.Exhibit 6 shows that automation is not a new phenomenon. Inthe 1950s, automation caused a large number of agricultureworkers to lose their jobs. In the 1990s, automation primarilyaffected manufacturing workers. As modern machines areincreasingly capable of undertaking routine cognitive labour,the impact of automation is widening. Advances in artificialintelligence—with machine learning techniques like deepneural networks allowing us to realise outcomes includingimage and speech recognition—mean computers are now ableto drive cars, trade stocks, detect fraud, and recognise speechto answer basic questions.Exhibit 6 shows that the services sector, traditionally shieldedfrom automation-related job losses, is fast becoming a primetarget for technology-driven productivity reforms.6 Over thepast decade, between 1 and 1.5 per cent of services jobshave disappeared due to technological change and otherproductivity improvements.While the data illustrates productivity-related job losses inthe US, a similar trend can be observed in Australia and otherdeveloped nations. In tourism, for example, the share ofAustralian holidaymakers who used official agents to receivetravel advice in 2013 had fallen to 37 per cent—15 per centless than in the year 2000. The culprit? The internet, whichis emerging as the top source of information for travellers.7Increasingly, automation is transforming the way we choose toreceive services.Such a disruption, although painful for indi

typically the most dangerous, least enjoyable and the least likely to be associated with high pay. As automation shifts these dangerous, tedious and less valuable tasks from people . Automation is causing Australian workers to rely more on their brains and personalities than on physical labour. By 2030, machines will likely take over 2 hours .