Transcription

Learning, Arts,and the BrainThe Dana Consortium Reporton Arts and Cognition

About DanaThe Dana Foundation is a private philanthropic organization with particularinterests in brain science, immunology, and education.In addition to making grants for research in neuroscience and immunology,Dana produces books and periodicals from the Dana Press; coordinates theinternational Brain Awareness week campaign; and supports the Dana Alliancefor Brain Initiatives, a nonprofit organization of more than 250 neuroscientists,including ten Nobel laureates, committed to advancing public awareness of theprogress of brain researchIn 2000 the Foundation extended its longtime aid to education to fundinnovative professional development programs leading to increased and improvedteaching of the performing arts.Dana’s focus is on training for in-school art specialists and professional artistswho teach in public schools. The arts education direct grants are supportedby providing information such as “best practices,” to arts educators, artists inresidence, teachers and students through symposia, periodicals, and books.The Dana Web site is at www.dana.orgThe Dana Foundation Board of DirectorsWilliam Safire, ChairmanEdward F. Rover, PresidentEdward BleierWallace L. CookCharles A. Dana IIISteven E. Hyman, M.D.Ann McLaughlin KorologosLasalle D. Leffall, M.D.Hildegarde E. MahoneyL. Guy Palmer, IIHerbert J. Siegel

Learning, Arts, and the BrainThe Dana Consortium Report on Arts and CognitionOrganized byMichael Gazzaniga, Ph.D.Edited by Carolyn Asbury, ScM.P.H., Ph.D.,and Barbara Rich, Ed.D.New York/Washington, D.C.

Copyright 2008 by Dana Press, all rights reservedPublished by Dana PressNew York/Washington, D.C.The Dana Foundation745 Fifth Avenue, Suite 900New York, NY 10151900 15th Street NWWashington, D.C. 20005DANA is a federally registered trademark.ISBN: 978-1-932594-36-2

ContentsSummaryArts and Cognition: Findings Hint at RelationshipsvMichael S. Gazzaniga, Ph.D.University of California at Santa Barbara1How Arts Training Influences Cognition2Musical Skill and Cognition3Effects of Music Instruction on Developing Cognitive Systemsat the Foundations of Mathematics and Science1Michael Posner, Ph.D., Mary K. Rothbart, Ph.D.,Brad E. Sheese, Ph.D., and Jessica Kieras, Ph.D.University of Oregon11John Jonides, Ph.D.University of Michigan17Elizabeth Spelke, Ph.D.Harvard University4Training in the Arts, Reading, and Brain Imaging5Dance and the Brain51Brian Wandell, Ph.D., Robert F. Dougherty, Ph.D.,Michal Ben-Shachar, Ph.D., Gayle K. Deutsch Ph.D.,and Jessica TsangStanford University61Scott Grafton, M.D. and Emily Cross, M.S.University of California at Santa Barbaraiii

ivTable of Contents6Developing and Implementing Neuroimaging Tools toDetermine if Training in the Arts Impacts the Brain71Mark D’Esposito, M.D.University of California, Berkeley7Arts Education, the Brain, and Language8Arts Education, the Brain, and Language9Effects of Music Training on Brain and CognitiveDevelopment in Under-Privileged 3- to 5-Year-OldChildren: Preliminary Results81Kevin Niall Dunbar, Ph.D.University of Toronto at Scarborough93Laura-Ann Petitto, Ed.D.University of Toronto105Helen Neville, Ph.D. and (in alphabetical order):Annika Andersson, M.S., Olivia Bagdade, B.A., Ted Bell, Ph.D.,Jeff Currin, B.A., Jessica Fanning, Ph.D., Scott Klein, B.A.,Brittni Lauinger, B.A., Eric Pakulak, M.S.,David Paulsen, M.S., Laura Sabourin, Ph.D.,Courtney Stevens, Ph.D., Stephanie Sundborg, M.S.,and Yoshiko Yamada, Ph.D.University of OregonAbout the Contributors and Editors117Acknowledgements127Index129

Arts and CognitionFindings Hint at RelationshipsMichael S. Gazzaniga, Ph.D.University of California at Santa BarbaraIn 2004, the Dana Arts and Cognition Consortium brought together cognitiveneuroscientists from seven universities across the United States to grapple with thequestion of why arts training has been associated with higher academic performance. Isit simply that smart people are drawn to “do” art—to study and perform music, dance,drama—or does early arts training cause changes in the brain that enhance other importantaspects of cognition?The consortium can now report findings that allow for a deeper understanding of howto define and evaluate the possible causal relationships between arts training and the abilityof the brain to learn in other cognitive domains.The research includes new data about the effects of arts training that should stimulatefuture investigation. The preliminary conclusions we have reached may soon lead totrustworthy assumptions about the impact of arts study on the brain; this should be helpfulto parents, students, educators, neuroscientists, and policymakers in making personal,institutional, and policy decisions.Specifics of each participating scientist’s research program are detailed in the appendedreports that can be downloaded from www.dana.org. Here is a summary of what thegroup has learned:1. An interest in a performing art leads to a high state of motivation that producesthe sustained attention necessary to improve performance and the training ofattention that leads to improvement in other domains of cognition.2. Genetic studies have begun to yield candidate genes that may help explainindividual differences in interest in the arts.3. Specific links exist between high levels of music training and the ability tomanipulate information in both working and long-term memory; these linksextend beyond the domain of music training.v

viArts and Cognition: Findings Hint at Relationships4. In children, there appear to be specificlinks between the practice of music andskills in geometrical representation,though not in other forms ofnumerical representation.5. Correlations exist between music trainingand both reading acquisition andsequence learning. One of the centralpredictors of early literacy, phonologicalawareness, is correlated with both musictraining and the development of a specificbrain pathway.6. Training in acting appears to lead tomemory improvement through thelearning of general skills for manipulatingsemantic information.7. Adult self-reported interest in aestheticsis related to a temperamental factor ofopenness, which in turn is influenced bydopamine-related genes.8. Learning to dance by effectiveobservation is closely related tolearning by physical practice, bothin the level of achievement and alsothe neural substrates that support theorganization of complex actions. Effectiveobservational learning may transfer toother cognitive skills.The foregoing advances our knowledge aboutthe relationship between arts and cognition. Theseadvances constitute a first round of a neuroscientificattack on the question of whether arts trainingchanges the brain to enhance general cognitivecapacities. The question is of such wide interest that,as with some organic diseases, insupportable answersgain fast traction and then ultimately boomerang.This is the particular difficulty of correlations;the weakness and even spuriousness of somecorrelational studies led to the creation of theconsortium. Correlation accompanies, parallels,complements or reciprocates, and is interesting toobserve, but only an understanding of mechanismsdrives action and change.Although scientists must constantly warn ofthe need to distinguish between correlation andcausation, it is important to realize that neuroscienceoften begins with correlations—usually, the discoverythat a certain kind of brain activity works in concertwith a certain kind of behavior. But in deciding whatresearch will be most productive, it matters whetherthese correlations are loose or tight. Many of thestudies cited here tighten up correlations that havebeen noted before, thereby laying the groundworkfor unearthing true causal explanations throughunderstanding biological and brain mechanisms thatmay underlie those relationships.Moreover, just as correlations may be tightor loose, causation may also be strong or weak.Theoretically, we could claim a broad causation,akin to “smoking causes cancer,” with randomizedprospective trials showing that children takingarts training can improve certain cognitive scores.Yet, even such a clear-cut result would be weakcausation, because we would not have found evenone brain mechanism of learning that could suggestprogress in understanding such mechanisms toguide optimal arts exposure. Nor would we havefound by what mechanisms the brain generalizesthat learning, nor anything about developmentalperiods where the brain is particularly sensitive togrowth from specific types of experience.A vast area of valuable research lies betweentight correlation and hard evidence based causalexplanations. Theory-driven questions usingcognitive neuroscience methods can go nts that demonstrate how changes in thebrain, as a result of arts training, enrich a person’slife, and how this experience is transferred todomains that enhance academic learning. Suchmid-ground studies would significantly advance ourknowledge even though they are not at the level ofcellular or molecular explanations.

Arts and Cognition: Findings Hint at RelationshipsThe consortium work on dance is a goodexample. Our research indicates that dancetraining can enable students to become highlysuccessful observers. We found that learning todance by watching alone can be highly successfuland that the success is sustained at the neural levelby a strong overlap between brain areas that areused for observing actions and also for makingactual movements. These shared neural substratesare critical for organizing complex actions intosequential structure. In the future we can test if thisskill in effective observation will transfer to otheracademic domains.Nailing down causal mechanisms in thecomplex circuitry of the brain is a tall order. Thearts and cognition studies by the Dana consortiumduring the past three years lay a foundation forunderstanding the mechanisms needed for action;we believe they offer the validity essential for thefuture studies that will build on them.A life-affirming dimension is opening up inneuroscience; to discover how the performance andappreciation of the arts enlarge cognitive capacitieswill be a long step forward in learning how betterto learn and more enjoyably and productively tolive. We offer several suggestions for extensions ofthe research reported herein:1. Previous work has established thatdifferent neural networks are involved invarious forms of the arts such as music,visual arts, drama and dance. Futurestudies should examine the degreeto which these networks are separateand overlap.2. We also require evidence of how highmotivation to pursue an art form will leadto more rapid changes in that networkand must find out to what degree suchchanges may influence other formsof cognition.3. The links between music and visualarts training and specific aspects ofmathematics such as geometry need to bemore profoundly explored with advancedimaging methods.4. The link between intrinsic motivationfor a specific art (e.g. music and visualarts) and sustained attention to tasksinvolving that art needs to be followed upwith increased behavioral evidence andimaging methods that can demonstratethat changes in specific pathways aregreater for higher levels of motivation.5. The search for individual indicators ofinterest in and influence by training in thearts should continue to be examined by acombination of appropriate questionnaireresearch, use of candidate genes alreadyidentified and whole genome scans.6. Further research also should posethese questions:a. To what degree is the link betweenmusic training, reading andsequence learning causative? If it iscausative, does it involve shapingof connectivity between areas ofthe brain network involved?b. Is the link between music anddrama training and memorymethods a causative one? If so,can we use brain imaging todetermine the mechanism?c. What is the role of carefulobservation and imitation inthe performing arts? Can weprepare our motor system forcomplex dance movements bysimply observing or imaginingdesired movements? Does thediscipline and cognitive skillto achieve this goal transfer?The consortium’s accomplishments to datehave included bringing together some of thevii

viiiArts and Cognition: Findings Hint at Relationshipsleading cognitive neuroscientists in the world tosort out correlative observations on the arts andcognition, and to begin the analysis of whetherthese relationships are causal. The consortium’snew findings and conceptual advances have clarifiedwhat now needs to be done. The specific suggestionsnoted above grow out of the project’s efforts—andsurely others are possible as well. These suggestionsrepresent a further deepening of a newly accessiblefield of investigation. Fresh results as well as newideas are presented herein on how to continue toresearch this topic.In my judgment, this project has identifiedcandidate genes involved in the predisposition to thearts and has also shown that cognitive improvementscan be made to specific mental capacities such asgeometric reasoning; that specific pathways in thebrain can be identified and potentially changedduring training; that sometimes it is not structuralbrain changes but rather changes in cognitivestrategy that help solve a problem; and that earlytargeted music training may lead to better cognitionthrough an as yet unknown neural mechanism. Thatis all rather remarkable and challenging.

How Arts TrainingInfluences CognitionMichael Posner, Ph.D., Mary K. Rothbart, Ph.D.,Brad E. Sheese, Ph.D., and Jessica Kieras, Ph.D.University of OregonSummaryIn our research, we studied how training in the arts can influence other cognitive processesthrough the underlying mechanism of attention. We also identified the neural network(system of connections between brain areas) from among the several involved in attentionthat is most likely to be influenced by arts training. Finally, we explored how individualdifferences in genes and temperament relate to the amount of improvement achieved,through attention training.We developed a theory about how arts training might work in which we hypothesizedthat: 1) there are specific brain networks for different art forms; 2) there is a general factorof interest or openness to the arts; 3) children with high interest in the arts, and withtraining in those arts, develop high motivation; 4) motivation sustains attention; and 5)high sustained motivation, while engaging in conflict-related tasks, improves cognition.The first two elements were tested through a questionnaire administered to adults. Wefound a statistically significant association between having an interest in a specific art formand producing that type of art. The questionnaire analyses also revealed that a generalaesthetic interest, or openness to the arts, was correlated with an appreciation of all of theart forms except dance. In our study, dance was confused between the art form and thesocial activity.We tested whether motivation sustains attention by randomly assigning children intoa control group, which performed a speeded task, or to an experimental group, in whichthe children performed tasks under motivating conditions of either reward or knowledgeof their results. We found that high levels of motivation led to strong improvements intask performance, particularly when motivation was sustained for longer periods of time.The findings support the idea that interest in the arts allows for sustained attention,1

2Learning, Arts and the Brainproviding an increased opportunity for the trainingto be effective.We also studied training of an executiveattentional network that is related to the selfregulation of cognition and emotion. Weassessed whether engaging in tasks designed toteach children how to resolve conflict improvescognition. We randomly assigned children to acontrol or intervention group. The interventionconsisted of five days of training on computerizedexercises of conflict resolution, under highlymotivating conditions.Children receiving attention training inconflict resolution under motivating conditions,compared to controls, showed significantly greaterimprovement on intelligence test scores. Thissuggests that the effects of attention traininggeneralized to a measure of cognitive processingthat extended far beyond the training exercises.Brain imaging using EEG (electroencephalophy,which records the brain’s electrical activity) alsoshowed that during executive attention tasks,trained children had patterns of activity similar tothose found in adults, while untrained children(control group) did not.Our genetics studies suggest that specific formsof several genes involved in the transmission of theneurotransmitter dopamine from one brain cellto another may be related to differences amongchildren and among adults in how efficientlythey resolve conflict. We are continuing thesegenetic studies.In our work, we used specific training exercisesdesigned to be engaging and motivating to improveattention. However, we believe that any trainingthat truly engages the interest of the child andmotivates the child can serve to help train attention.Our findings indicate that arts training could workthrough the training of attention to improvecognition for those with an interest and ability inthe arts.IntroductionWe have been investigating an executive attentionalnetwork of connections between brain areas thatappears to be an important underlying foundationof cognitive improvements related to arts training.This executive attention network is related to theself-regulation of cognition and emotion (Posnerand Rothbart, 2007a,b; Rothbart and Rueda,2005; Rueda, Posner, and Rothbart, 2004). Thenetwork involves specific brain areas, including the executive attention plays animportant role in the child’severyday control of thoughts,feelings and behavior midline and lateral frontal areas (Fan, McCandlisset al 2005a). We have shown that the efficiencyof executive attention is related to a higher orderfactor in parental reports about their children calledeffortful control (Rothbart and Rueda, 2005).Thus executive attention plays an important role inthe child’s everyday control of thoughts, feelings,and behavior that can be observed and reported bytheir parents. this attentional brain networkis related to self-regulationof cognition and emotion.The ability to study the executive attentionalnetwork is enhanced by progress in neuroimaging(Posner and Rothbart, 2007a) and in sequencingthe human genome (Posner, Rothbart, and Sheese,2007; Venter et al, 2002). These two scientificfields make it possible to consider high levelcognitive skills in terms of experiential and genetic

How Arts Training Influences Cognitionfactors that shape the development of underlyingbrain networks (systems of connections betweenbrain areas).Our previous extensive studies on the processesof attention used by infants and children haveestablished that this attentional brain network isrelated to self-regulation of cognition and emotion.It is involved in attending to high level skills,including making word associations. For instance,during the act of attending to one language whilesuppressing related responses in another language,the executive attentional network is the one mostlikely to be active. individual differencesin the development of theexecutive attentional networkare related to differencesin brain areas that areinvolved in high level skills.In this research, we studied the network’sdevelopment in children ranging from two-andone-half to seven years of age (Rueda et al., 2004).Additionally, we asked parents of the childrenenrolled in our study to fill out a self-reportquestionnaire. We examined children’s abilities toself-regulate cognition and emotion. The childrenwere tested on a number of conflict tasks (Fan,Flombaum et al., 2003), which have been shown toactivate the executive attentional network.Individual differences among children indevelopment of this network were related toparents’ reports of the degree to which theirchildren were able to regulate their own behavior(Rothbart and Rueda, 2005) and to their abilityto delay rewards. Additionally, through imagingstudies, it was found that individual differencesin the development of the executive attentionalnetwork are related to differences in the activationof brain areas that are involved in high-level skills(Posner and Rothbart, 2007b).Through genetic studies, it has been shown thatspecific forms of several dopamine and serotoningenes were related to differences in the efficiencywith which conflict is resolved. Two of these geneshave also been related to activation of the partof the executive attention network located in thebrain’s cingulate gyrus (Fan, Fossella et al., 2005).Based on these findings, we had adapted a setof exercises, developed from animal studies, totrain developmentally healthy four and six yearolds to focus their attention. We randomized thechildren into two groups: an attention traininggroup (experimental group) and a “control”group who interacted with videos not designed toimprove attention.Childrenintheexperimentalgroup,compared to those in the control group, showedgreater improvement in IQ measures, showinggeneralization beyond the direct measures ofattention (Rueda, Rothbart, Saccamanno, andPosner, 2005; 2007).Our HypothesesWe considered it as important to have anexplanation of how the arts influence cognition, asit is to have evidence that arts training influencescognition. We hypothesized, therefore, that thebrain network involved in executive attention andeffortful control can be strengthened by specificlearning. Moreover, we hypothesized that theenthusiasm that many young people have for music,art, and performance could provide a context forpaying close attention. This motivation could,in turn, lead to improvement in the attentionnetwork, which would then generalize to a range ofcognitive skills.Our training study supported this proposedtheory about the mechanisms by which training in3

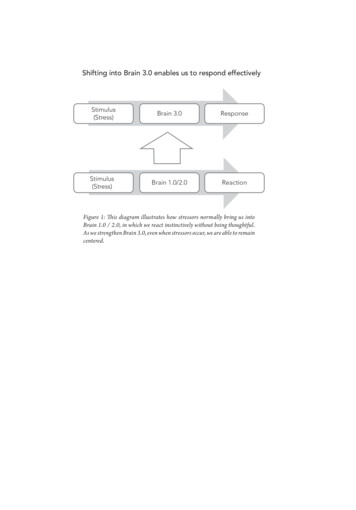

4Learning, Arts and the BrainInterest in aesthetics, or openness to an interestin the arts, has been found in studies of adults tobe related to specific forms of genes that directthe production of the neurotransmitter dopamine.Some of these same genes have also been related tothe efficiency of executive attention, which in turnis modulated by dopamine.Elements of the Arts TheoryFigure 1the arts can have a persistent effect on a wide varietyof cognitive processes.The theory is based on the idea that eachindividual art form involves separate brain networks.In Figure 1, we summarize some of the specificbrain areas involved in different art forms.The theory is that eachindividual art form involvesseparate brain networks.The results from the parents’ questionnairesuggest that there is some variation in a child’sdegree of interest in different art forms. In addition,interest in each of the arts indicated in Figure 1 iscorrelated with a General Arts Interest factor.This General Arts Interest factor was itselfcorrelated with a temperamental characteristiccalled “Orienting Sensitivity” (Rothbart, Ahadi, andEvans, 2000; Evans and Rothbart, 2008). OrientingSensitivity is, in turn, strongly related to the BigFive-personality factor of openness. Therefore, werelated the degree of general arts interest with thepersonality factor of openness.Our theory of how interest and training in thearts leads to improved general cognition generally,involves five elements. They are listed below, andthen discussed.1. There are specific brain networksfor different art forms.2. There is a general factor ofinterest in the arts.3. When this general factor ofinterest in the arts is high,training in an appropriate specificart form produces high interest ormotivation.4. This interest or motivationsustains attention.5. High sustained attention inconflict-related tasks, of the typeused in our attention–trainingstudies improves cognition.Study Design and ResultsTo explore the first three elements of our theory,we constructed a questionnaire based on the Evansand Rothbart’s Adult Temperament Scale (ATQ)(Evans and Rothbart, 2007). We also added anumber of aesthetics questions listed below thatwere developed by Victor, Rothbart, and Baker (inpreparation). The questionnaire was administeredto samples of University of Oregon undergraduatesand to a sample of adult residents of the communityof Bend, Oregon.

How Arts Training Influences CognitionGeneral Aesthetic ActivityPerception ItemsProduction ItemsI like to paint or draw.I show a lot of imagination.I like to look at art.I am creative.I enjoy listening to music.I am artistic.I like watching plays.I like making sculptures orceramics.I would enjoy playing amusical instrument.I enjoy photography orfilmmaking.I like to write.I like dancing.Table 1: Structure of the Aesthetics QuestionnaireElement 1: Appreciation of Art Relatesto Pleasure in Producing that ArtElement 2: Appreciation of an Art FormRelates to General Aesthetic InterestWe tested the hypothesis that an appreciationof a specific type of art was related to pleasure inproducing that type of art. We correlated responsesto questionnaire items that assessed interest inperceiving and producing specific art forms.Interest in looking at art was correlated withinterest in painting/drawing r .48. The correlation,termed “r” reflects the relation between observingarts and producing the art. This correlation wassignificant statistically, meaning that it was unlikelyto be present by chance alone. Similarly, interestin making ceramics or sculptures was statisticallycorrelated with pleasure in producing that type ofart (r .42, p .01). Interest in listening to musicwas correlated with interest in playing a musicalinstrument (r .31, p .01). Interest in watchingplays was correlated with interest in photographyor filmmaking (r .33, p .01) and interest inwriting (r .28, p .01).We tested the hypothesis that appreciation ofspecific types of art is related to general aestheticinterest. We computed a score for “general aestheticinterest” by calculating the average (“mean”) ofnon-specific artistic items (“I am creative,” “I amartistic,” “I show a lot of imagination”). We lookedfor correlations between this average score and eachitem that assessed interest in a specific art form.All of the specific art form items weresignificantly (p .05) correlated with the score ongeneral aesthetic interest, except “I like dancing.”The median correlation was r .35 for all of theitems except dancing.These results also showed that the generalaesthetics factor (Table 1, Row 1) was highlycorrelated with the temperament factor of orientingsensitivity (openness).5

6Learning, Arts and the BrainElement 3: High Interest isLinked to High MotivationThis element links training in appropriate arts withmotivation. The link between arts training andmotivation, though plausible, remains speculative,and needs to be tested through experimentalresearch. We postulate that children who have ahigh level of orienting sensitivity (openness) andat least normal interest in a particular art will havehigh motivation to receive training in that art.Our research has providedevidence that motivationsustains attention.Element 4: Motivation Sustains AttentionOur research has provided evidence that motivationsustains attention. We found, in children agedfour-and-one-half and seven years old, that highlevels of motivation, as induced by reward andfeedback, led to strong improvements in sustainedattention (Kieras, 2006). When feedback andreward were used to heighten motivation, childrenshowed improved levels of alerting during a task.We found that children performing the task undermotivating conditions sustained their attentionover longer periods of time compared to childrenwho performed the task in the absence of suchmotivating conditions.We propose, based on these findings, that artstraining for those with a high level of interest wouldallow for sustained attention, thereby increasing theopportunity for training to be effective.Element 5: High Sustained Attentionon Conflict Tasks Improves CognitionWe have published evidence that one form ofattention training does, in fact, improve theunderlying network that is involved in executiveattention for effortful control of cognition andemotion (Rueda, et al, 2005). To examine the roleof experience on the executive attentional network,we developed and tested a five-day trainingintervention that uses computerized exercises.The exercises were designed to be interesting andmotivating to young children in just the way thatwe assume arts training to be for children with theappropriate interests.We tested the effect of this training interventionduring the period of major development of executiveattention, in children between the ages of four andseven (Rueda, Posner, Rothbart, and Davis-Stober,2004). We hypothesized that children trained inattention related to effortful control of cognitionand emotion would show improvement in conflictresolution by changes in the underlying executiveattentional network; and we hypothesized that thiseffect would be generalized to other aspects ofcognition.To test this hypothesis, we used EEGs(electroencephalograms), electrodes that are placedon the scalp and record electrical activity of thebrain. Our EEG data showed clear evidence thattraining improved the efficiency of the executiveattentional network in resolving conflict.The technical explanation is that the “N2”component of the scalp-recorded ERP (eventrelated potential, which is an electrical response toa specific stimulus) has been shown to arise in thebrain’s anterior “cingulate” region, and is related tothe resolution of conflict (Rueda, et al, 2004; vanVeen and Carter, 2002). We found N2 differencesbetween congruent (matched) and incongruenttrials of the Attentional Network Te

memory improvement through the learning of general skills for manipulating semantic information. 7. Adult self-reported interest in aesthetics is related to a temperamental factor of openness, which in turn is influenced by dopamine-related genes. 8. Learning to dance by effective observatio