Transcription

ISSUE BRIEFApril 2015Understanding theEffects of Maltreatmenton Brain DevelopmentIn recent years, there has been a surgeof research into early brain development.Neuroimaging technologies, such as magneticresonance imaging (MRI), provide increasedinsight about how the brain develops and howearly experiences affect that development.WHAT’S INSIDEHow the brain developsEffects of maltreatmenton brain developmentImplications forpractice and policySummaryAdditional resourcesOne area that has been receiving increasingresearch attention involves the effects ofabuse and neglect on the developing brain,especially during infancy and early childhood.Much of this research is providing biologicalexplanations for what practitioners havelong been describing in psychological,emotional, and behavioral terms. Thereis now scientific evidence of altered brainfunctioning as a result of early abuse andneglect. This emerging body of knowledgehas many implications for the preventionand treatment of child abuse and neglect.Children’s Bureau/ACYF/ACF/HHS800.394.3366 Email: info@childwelfare.gov https://www.childwelfare.govReferences

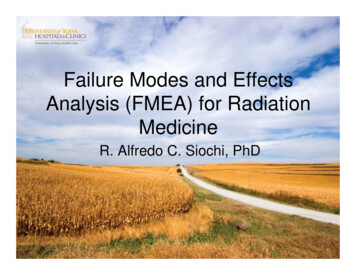

https://www.childwelfare.govUnderstanding the Effects of Maltreatment on Brain DevelopmentThis issue brief provides basic information ontypical brain development and the potential effectsof abuse and neglect on that development. Theinformation is designed to help professionalsunderstand the emotional, mental, and behavioralimpact of early abuse and neglect in children whocome to the attention of the child welfare system.grow rapidly in the first 3 years of life (ZERO TOTHREE, 2012). (See Exhibit 1 for more information.)Exhibit 1 – Functions of Brain RegionsCortexHow the Brain DevelopsWhat we have learned about the process of braindevelopment helps us understand more about theroles both genetics and the environment play in ourdevelopment. It appears that genetics predispose us todevelop in certain ways, but our experiences, includingour interactions with other people, have a significantimpact on how our predispositions are expressed.In fact, research now shows that many capacitiesthought to be fixed at birth are actually dependent ona sequence of experiences combined with heredity.Both factors are essential for optimum developmentof the human brain (Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000).Early Brain DevelopmentThe raw material of the brain is the nerve cell, calledthe neuron. During fetal development, neurons arecreated and migrate to form the various parts of thebrain. As neurons migrate, they also differentiate, orspecialize, to govern specific functions in the bodyin response to chemical signals (Perry, 2002). Thisprocess of development occurs sequentially fromthe “bottom up,” that is, from areas of the braincontrolling the most primitive functions of the body(e.g., heart rate, breathing) to the most sophisticatedfunctions (e.g., complex thought) (Perry, 2000a).The first areas of the brain to fully develop are thebrainstem and midbrain; they govern the bodily functionsnecessary for life, called the autonomic functions.At birth, these lower portions of the nervous systemare very well developed, whereas the higher regions(the limbic system and cerebral cortex) are still ratherprimitive. Higher function brain regions involved inregulating emotions, language, and abstract thoughtLimbicMidbrainBrainstemBruce D. Perry, M.D., Ph.D.www.ChildTrauma.orgHigherAbstract ThoughtConcrete ThoughtAffiliationAttachmentSexual BehaviorEmotional ReactivityMotor RegulationArousalAppetite/SatietySleepBlood PressureHeart RateBody TemperatureLowerThe Growing Child’s BrainBrain development, or learning, is actually the processof creating, strengthening, and discarding connectionsamong the neurons; these connections are calledsynapses. Synapses organize the brain by formingpathways that connect the parts of the brain governingeverything we do—from breathing and sleeping tothinking and feeling. This is the essence of postnatalbrain development, because at birth, very few synapseshave been formed. The synapses present at birthare primarily those that govern our bodily functionssuch as heart rate, breathing, eating, and sleeping.The development of synapses occurs at an astoundingrate during a child’s early years in response to that child’sexperiences. At its peak, the cerebral cortex of a healthytoddler may create 2 million synapses per second (ZEROTO THREE, 2012). By the time children are 2 years old,their brains have approximately 100 trillion synapses,many more than they will ever need. Based on thechild’s experiences, some synapses are strengthenedand remain intact, but many are gradually discarded.This process of synapse elimination—or pruning—isa normal part of development (Shonkoff & Phillips,2000). By the time children reach adolescence, abouthalf of their synapses have been discarded, leaving thenumber they will have for most of the rest of their lives.This material may be freely reproduced and distributed. However, when doing so, please credit Child Welfare InformationGateway. This publication is available online at in-development.2

Understanding the Effects of Maltreatment on Brain DevelopmentAnother important process that takes place in thedeveloping brain is myelination. Myelin is the white fattytissue that forms a sheath to insulate mature brain cells,thus ensuring clear transmission of neurotransmittersacross synapses. Young children process informationslowly because their brain cells lack the myelinnecessary for fast, clear nerve impulse transmission(ZERO TO THREE, 2012). Like other neuronal growthprocesses, myelination begins in the primary motorand sensory areas (the brain stem and cortex) andgradually progresses to the higher-order regions thatcontrol thought, memories, and feelings. Also, like otherneuronal growth processes, a child’s experiences affectthe rate and growth of myelination, which continuesinto young adulthood (Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000).By 3 years of age, a baby’s brain has reached almost90 percent of its adult size. The growth in eachregion of the brain largely depends on receivingstimulation, which spurs activity in that region. Thisstimulation provides the foundation for learning.Adolescent Brain DevelopmentStudies using MRI techniques show that the braincontinues to grow and develop into young adulthood (atleast to the midtwenties). White matter, or brain tissue,volume has been shown to increase in adults as old as 32(Lebel & Beaulieu, 2011). Right before puberty, adolescentbrains experience a growth spurt that occurs mainly inthe frontal lobe, which is the area that governs planning,impulse control, and reasoning. During the teenageyears, the brain goes through a process of pruningsynapses—somewhat like the infant and toddler brain—and also sees an increase in white matter and changes toneurotransmitter systems (Konrad, Firk, & Uhlhaas, 2013).As the teenager grows into young adulthood, the braindevelops more myelin to insulate the nerve fibers andspeed neural processing, and this myelination occurs lastin the frontal lobe. MRI comparisons between the brainsof teenagers and the brains of young adults have shownthat most of the brain areas were the same—that is, theteenage brain had reached maturity in the areas thatgovern such abilities as speech and sensory capabilities.https://www.childwelfare.govThe major difference was the immaturity of the teenagebrain in the frontal lobe and in the myelination of thatarea (National Institute of Mental Health, 2001).Normal puberty and adolescence lead to thematuration of a physical body, but the brain lagsbehind in development, especially in the areas thatallow teenagers to reason and think logically. Mostteenagers act impulsively at times, using a lower areaof their brains—their “gut reaction”—because theirfrontal lobes are not yet mature. Impulsive behavior,poor decisions, and increased risk-taking are all partof the normal teenage experience. Another changethat happens during adolescence is the growth andtransformation of the limbic system, which is responsiblefor our emotions. Teenagers may rely on their moreprimitive limbic system in interpreting emotions andreacting since they lack the more mature cortex thatcan override the limbic response (Chamberlain, 2009).Plasticity—The Influence of EnvironmentResearchers use the term plasticity to describe the brain’sability to change in response to repeated stimulation.The extent of a brain’s plasticity is dependent on thestage of development and the particular brain systemor region affected (Perry, 2006). For instance, the lowerparts of the brain, which control basic functions suchas breathing and heart rate, are less flexible, or plastic,than the higher functioning cortex, which controlsthoughts and feelings. While cortex plasticity decreasesas a child gets older, some degree of plasticity remains.In fact, this brain plasticity is what allows us to keeplearning into adulthood and throughout our lives.The developing brain’s ongoing adaptations are theresult of both genetics and experience. Our brainsprepare us to expect certain experiences by formingthe pathways needed to respond to those experiences.For example, our brains are “wired” to respond to thesound of speech; when babies hear people speaking,the neural systems in their brains responsible for speechand language receive the necessary stimulation toorganize and function (Perry, 2006). The more babies areThis material may be freely reproduced and distributed. However, when doing so, please credit Child Welfare InformationGateway. This publication is available online at in-development.3

https://www.childwelfare.govUnderstanding the Effects of Maltreatment on Brain Developmentexposed to people speaking, the stronger their relatedsynapses become. If the appropriate exposure doesnot happen, the pathways developed in anticipationmay be discarded. This is sometimes referred to as theconcept of “use it or lose it.” It is through these processesof creating, strengthening, and discarding synapsesthat our brains adapt to our unique environment.they were 24 months old (Smyke, Zeanah, Fox, Nelson,& Guthrie, 2010). This indicates that there is a sensitiveperiod for attachment, but it is likely that there is ageneral sensitive period rather than a true cut-off point forrecovery (Zeanah, Gunnar, McCall, Kreppner, & Fox, 2011).The ability to adapt to our environment is a part of normaldevelopment. Children growing up in cold climates,on rural farms, or in large sibling groups learn how tofunction in those environments. Regardless of the generalenvironment, though, all children need stimulationand nurturance for healthy development. If these arelacking (e.g., if a child’s caretakers are indifferent, hostile,depressed, or cognitively impaired), the child’s braindevelopment may be impaired. Because the brain adaptsto its environment, it will adapt to a negative environmentjust as readily as it will adapt to a positive one.While sensitive periods exist for development andlearning, we also know that the plasticity of the brainoften allows children to recover from missing certainexperiences. Both children and adults may be ableto make up for missed experiences later in life, butit is likely to be more difficult. This is especially trueif a young child was deprived of certain stimulation,which resulted in the pruning of synapses (neuronalconnections) relevant to that stimulation and the loss ofneuronal pathways. As children progress through eachdevelopmental stage, they will learn and master eachstep more easily if their brains have built an efficientnetwork of pathways to support optimal functioning.Sensitive PeriodsMemoriesResearchers believe that there are sensitive periodsfor development of certain capabilities. These refer towindows of time in the developmental process whencertain parts of the brain may be most susceptible toparticular experiences. Animal studies have shed lighton sensitive periods, showing, for example, that animalsthat are artificially blinded during the sensitive period fordeveloping vision may never develop the capability tosee, even if the blinding mechanism is later removed.The organizing framework for children’s developmentis based on the creation of memories. When repeatedexperiences strengthen a neuronal pathway, the pathwaybecomes encoded, and it eventually becomes a memory.Children learn to put one foot in front of the other towalk. They learn words to express themselves. And theylearn that a smile usually brings a smile in return. At somepoint, they no longer have to think much about theseprocesses—their brains manage these experienceswith little effort because the memories that have beencreated allow for a smooth, efficient flow of information.It is more difficult to study human sensitive periods, butwe know that, if certain synapses and neuronal pathwaysare not repeatedly activated, they may be discarded,and their capabilities may diminish. For example, infantshave a genetic predisposition to form strong attachmentsto their primary caregivers, but they may not be able toachieve strong attachments, or trusting, durable bondsif they are in a severely neglectful situation with littleone-on-one caregiver contact. Children from Romanianinstitutions who had been severely neglected had a muchbetter attachment response if they were placed in fostercare—and thus received more stable parenting—beforeThe creation of memories is part of our adaptation to ourenvironment. Our brains attempt to understand the worldaround us and fashion our interactions with that world in away that promotes our survival and, hopefully, our growth,but if the early environment is abusive or neglectful, ourbrains may create memories of these experiences thatadversely color our view of the world throughout our life.Babies are born with the capacity for implicit memory,which means that they can perceive their environmentThis material may be freely reproduced and distributed. However, when doing so, please credit Child Welfare InformationGateway. This publication is available online at in-development.4

Understanding the Effects of Maltreatment on Brain Developmentand recall it in certain unconscious ways (Applegate& Shapiro, 2005). For instance, they recognize theirmother’s voice from an unconscious memory. Theseearly implicit memories may have a significant impacton a child’s subsequent attachment relationships.In contrast, explicit memory, which develops aroundage 2, refers to conscious memories and is tied tolanguage development. Explicit memory allows childrento talk about themselves in the past and future or indifferent places or circumstances through the processof conscious recollection (Applegate & Shapiro, 2005).Sometimes, children who have been abused or sufferedother trauma may not retain or be able to access explicitmemories of their experiences; however, they may retainimplicit memories of the physical or emotional sensations,and these implicit memories may produce flashbacks,nightmares, or other uncontrollable reactions (Applegate& Shapiro, 2005). This may be the case with very youngchildren or infants who suffer abuse or neglect.Responding to StressWe all experience different types of stress throughoutour lives. The type of stress and the timing of that stressdetermine whether and how there is an impact on thebrain. The National Scientific Council on the DevelopingChild (2014) outlines three classifications of stress: Positive stress is moderate, brief, and generally anormal part of life (e.g., entering a new child caresetting). Learning to adjust to this type of stress is anessential component of healthy development. Tolerable stress includes events that have thepotential to alter the developing brain negatively, butwhich occur infrequently and give the brain time torecover (e.g., the death of a loved one). Toxic stress includes strong, frequent, and prolongedactivation of the body’s stress response system (e.g.,chronic neglect).Healthy responses to typical life stressors (i.e., positiveand tolerable stress events) are very complex and mayhttps://www.childwelfare.govchange depending on individual and environmentalcharacteristics, such as genetics, the presence of asensitive and responsive caregiver, and past experiences.A healthy stress response involves a variety of hormoneand neurochemical systems throughout the body,including the sympathetic-adrenomedullary (SAM) system,which produces adrenaline, and the hypothalamicpituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) system, which producescortisol (National Council on the Developing Child, 2014).Increases in adrenaline help the body engage energystores and alter blood flow. Increases in cortisol also helpthe body engage energy stores and also can enhancecertain types of memory and activate immune responses.In a healthy stress response, the hormonal levels willreturn to normal after the stressful experience has passed.Effects of Maltreatment onBrain DevelopmentJust as positive experiences can assist with healthybrain development, children’s experiences with childmaltreatment or other forms of toxic stress, such asdomestic violence or disasters, can negatively affect braindevelopment. This includes changes to the structureand chemical activity of the brain (e.g., decreased sizeor connectivity in some parts of the brain) and in theemotional and behavioral functioning of the child (e.g.,over-sensitivity to stressful situations). For example,healthy brain development includes situations in whichbabies’ babbles, gestures, or cries bring reliable,appropriate reactions from their caregivers. Thesecaregiver-child interactions—sometimes referred toas “serve and return”—strengthen babies’ neuronalpathways regarding social interactions and how to gettheir needs met, both physically and emotionally. Ifchildren live in a chaotic or threatening world, one inwhich their caregivers respond with abuse or chronicallyprovide no response, their brains may become hyperalertfor danger or not fully develop. These neuronal pathwaysthat are developed and strengthened under negativeconditions prepare children to cope in that negativeenvironment, and their ability to respond to nurturing andkindness may be impaired (Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000).This material may be freely reproduced and distributed. However, when doing so, please credit Child Welfare InformationGateway. This publication is available online at in-development.5

Understanding the Effects of Maltreatment on Brain DevelopmentThe specific effects of maltreatment may dependon such factors as the age of the child at the timeof the maltreatment, whether the maltreatment wasa one-time incident or chronic, the identity of theabuser (e.g., parent or other adult), whether the childhad a dependable nurturing individual in his or herlife, the type and severity of the maltreatment, theintervention, how long the maltreatment lasted, andother individual and environmental characteristics.Effects of Maltreatment on BrainStructure and ActivityToxic stress, including child maltreatment, can havea variety of negative effects on children’s brains: Hippocampus: Adults who were maltreated mayhave reduced volume in the hippocampus, which iscentral to learning and memory (McCrory, De Brito, &Viding, 2010; Wilson, Hansen, & Li, 2011). Toxic stressalso can reduce the hippocampus’s capacity to bringcortisol levels back to normal after a stressful event hasoccurred (Shonkoff, 2012). Corpus callosum: Maltreated children andadolescents tend to have decreased volume in thecorpus callosum, which is the largest white matterstructure in the brain and is responsible for interhemispheric communication and other processes (e.g.,arousal, emotion, higher cognitive abilities) (McCrory,De Brito, & Viding, 2010; Wilson, Hansen, & Li, 2011). Cerebellum: Maltreated children and adolescentstend to have decreased volume in the cerebellum,which helps coordinate motor behavior and executivefunctioning (McCrory, De Brito, & Viding, 2010). Prefrontal cortex: Some studies on adolescentsand adults who were severely neglected as childrenindicate they have a smaller prefrontal cortex, which iscritical to behavior, cognition, and emotion regulation(National Scientific Council on the Developing Child,2012), but other studies show no differences (McCrory,De Brito, & Viding, 2010). Physically abused childrenalso may have reduced volume in the orbitofrontalcortex, a part of the prefrontal cortex that is central toemotion and social regulation (Hanson et al., 2010).https://www.childwelfare.gov Amygdala: Although most studies have found thatamygdala volume is not affected by maltreatment,abuse and neglect can cause overactivity in that areaof the brain, which helps determine whether a stimulusis threatening and trigger emotional responses(National Scientific Council on the Developing Child,2010b; Shonkoff, 2012). Cortisol levels: Many maltreated children, both ininstitutional and family settings, and especially thosewho experienced severe neglect, tend to have lowerthan normal morning cortisol levels coupled withflatter release levels throughout the day (Bruce, Fisher,Pears, & Levine, 2009; National Scientific Council onthe Developing Child, 2012). (Typically, children havea sharp increase in cortisol in the morning followedby a steady decrease throughout the day.) On theother hand, children in foster care who experiencedsevere emotional maltreatment had higher thannormal morning cortisol levels. These results maybe due to the body reacting differently to differentstressors. Abnormal cortisol levels can have manynegative effects. Lower cortisol levels can lead todecreased energy resources, which could affectlearning and socialization; externalizing disorders;and increased vulnerability to autoimmune disorders(Bruce, Fisher, Pears, & Levine, 2009). Higher cortisollevels could harm cognitive processes, subdue immuneand inflammatory reactions, or heighten the risk foraffective disorders. Other: Children who experienced severe neglectearly in life while in institutional settings often havedecreased electrical activity in their brains, decreasedbrain metabolism, and poorer connections betweenareas of the brain that are key to integrating complexinformation (National Scientific Council on theDeveloping Child, 2012). These children also maycontinue to have abnormal patterns of adrenalineactivity years after being adopted from institutionalsettings. Additionally, malnutrition, a form of neglect,can impair both brain development (e.g., slowing thegrowth of neurons, axons, and synapses) and function(e.g., neurotransmitter syntheses, the maintenance ofbrain tissue) (Prado & Dewey, 2012).This material may be freely reproduced and distributed. However, when doing so, please credit Child Welfare InformationGateway. This publication is available online at in-development.6

https://www.childwelfare.govUnderstanding the Effects of Maltreatment on Brain DevelopmentExhibit 2 provides an illustration of these brain areas.EpigeneticsExhibit 2—Brain DiagramCredit: Tapert, S. F., Caldwell, L., & Burke, C. (2004/2005).Alcohol and the adolescent brain: Human studies.Alcohol Research & Health, 28(4), 205–212.We also know that some cases of physical abuse cancause immediate direct structural damage to a child’sbrain. For example, according to the National Centeron Shaken Baby Syndrome (n.d.), shaking a child candestroy brain tissue and tear blood vessels. In the shortterm, this can lead to seizures, loss of consciousness,or even death. In the long-term, shaking can damagethe fragile brain so that a child develops a range ofsensory impairments, as well as cognitive, learning,and behavioral disabilities. Other types of head injuriescaused by physical abuse can have similar effects.A burgeoning field of research related to braindevelopment is epigenetics. Epigenetics refersto alterations to the genes that do not includestructural changes to the DNA nucleotidesequence (Orr & Kaufman, 2014). An epigeneticmodification occurs when chemical “signatures”attach themselves to genes, which, in turn, helpsdetermine how the genes are expressed (i.e.,whether they are turned on or off). These changescan affect the expression of genes in brain cells,may be permanent or temporary, and can beinherited by the person’s offspring (NationalScientific Council on the Developing Child, 2010a).The chemical experiences are initiated by lifeexperiences, both positive and negative, as well asnutrition and exposure to toxins or drugs (NationalScientific Council on the Developing Child, 2010a).Although the field of epigenetics is still in its infancy,studies have indicated that child maltreatmentcan cause epigenetic modifications in victims. Inone study of individuals with posttraumatic stressdisorder (PTSD), those who had been maltreatedas children exhibited more epigenetic changesin genes associated with central nervous systemdevelopment and immune system regulation thannonmaltreated individuals with PTSD (Mehta etal., 2013). Furthermore, the findings indicatedthat the maltreated individuals had up to 12 timesmore epigenetic changes than nonmaltreatedindividuals, which may mean that maltreatedindividuals may experience PTSD uniquely andmay require different types of treatment thanother groups with PTSD. Another study founddecreased hippocampal glucocorticoid receptorexpression, which affects HPA activity, in suicidevictims with histories of child abuse compared tononabused suicide victims (McGowan et al., 2009).This material may be freely reproduced and distributed. However, when doing so, please credit Child Welfare InformationGateway. This publication is available online at in-development.7

Understanding the Effects of Maltreatment on Brain Developmenthttps://www.childwelfare.govEffects of Maltreatment on Behavioral,Social, and Emotional Functioningon alert and are unable to achieve the relative calmnecessary for learning (Child Trauma Academy, n.d.).The changes in brain structure and chemicalactivity caused by child maltreatment can have awide variety of effects on children’s behavioral,social, and emotional functioning.Increased Internalizing Symptoms. Child maltreatmentcan lead to structural and chemical changes in the areasof the brain involved in emotion and stress regulation(National Scientific Council on the Developing Child,2010b). For example, maltreatment can affect connectivitybetween the amygdala and hippocampus, which canthen initiate the development of anxiety and depressionby late adolescence (Herringa et al., 2013). Additionally,early emotional abuse or severe deprivation maypermanently alter the brain’s ability to use serotonin,a neurotransmitter that helps produce feelings ofwell-being and emotional stability (Healy, 2004).Persistent Fear Response. Chronic stress or repeatedtrauma can result in a number of biological reactions,including a persistent fear state (National ScientificCouncil on the Developing Child, 2010b). Chronicactivation of the neuronal pathways involved in the fearresponse can create permanent memories that shape thehild’s perception of and response to the environment.While this adaptation may be necessary for survivalin a hostile world, it can become a way of life that isdifficult to change, even if the environment improves.Children with a persistent fear response may lose theirability to differentiate between danger and safety, andthey may identify a threat in a nonthreatening situation(National Scientific Council on the Developing Child,2010b). For example, a child who has been maltreatedmay associate the fear caused by a specific person orplace with similar people or places that pose no threat.This generalized fear response may be the foundationof future anxiety disorders, such as PTSD (NationalScientific Council on the Developing Child, 2010b).Hyperarousal. When children are exposed to chronic,traumatic stress, their brains sensitize the pathways forthe fear response and create memories that automaticallytrigger that response without conscious thought. Thisis called hyperarousal. These children may be highlysensitive to nonverbal cues, such as eye contact ora touch on the arm, and they may be more likely tomisinterpret them (National Scientific Council on theDeveloping Child, 2010b). Consumed with a need tomonitor nonverbal cues for threats, their brains areless able to interpret and respond to verbal cues, evenwhen they are in an environment typically considerednonthreatening, like a classroom. While these childrenare often labeled as learning disabled, the reality is thattheir brains have developed so that they are constantlyDiminished Executive Functioning. Executivefunctioning generally includes three components:working memory (being able to keep and use informationover a short period of time), inhibitory control (filteringthoughts and impulses), and cognitive or mentalflexibility (adjusting to changed demands, priorities,or perspectives) (National Scientific Council on theDeveloping Child, 2011). The structural and neurochemicaldamage caused by maltreatment can create deficits inall areas of executive functioning, even at an early age(Hostinar, Stellern, Schaefer, Carlson, & Gunnar, 2012;National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2011).Executive functioning skills help people achieve academicand career success, bolster social interactions, and assistin everyday activities. The brain alterations caused bya toxic stress response can result in lower academicachievement, intellectual impairment, decreased IQ, andweakened ability to maintain attention (Wilson, 2011).Delayed Developmental Milestones. Although neglectoften is thought of as a fail

years, the brain goes through a process of pruning synapses—somewhat like the infant and toddler brain— and also sees an increase in white matter and changes to neurotransmitter systems (Konrad, Firk, & Uhlhaas, 2013). As the teenager grows into young adulthood, the brain

![[digital] Visual Effects and Compositing](/img/1/9780321984388.jpg)