Transcription

The Origin of the New TestamentbyAdolf Harnack

About The Origin of the New Testament by Adolf HarnackTitle:URL:Author(s):Publisher:Rights:Date Created:General Comments:CCEL Subjects:The Origin of the New Testamenthttp://www.ccel.org/ccel/harnack/origin nt.htmlHarnack, Adolf (1851-1930)Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal LibraryPublic Domain2005-04-20(tr. The Rev. J. R. Wilkinson)All; Bible

The Origin of the New TestamentAdolf HarnackTable of ContentsAbout This Book. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . p. iiTitle Page. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . p. 1Prefatory Material. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . p. 2I. The Needs and Motive Forces that Led to the Creation of the NewTestament. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . p. 12§ 1. How did the Church arrive at a second authoritative Canon in additionto the Old Testament?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . p. 13§ 2. Why is it that the New Testament also contains other books besidethe Gospels, and appears as a compilation with two divisions (“Evangelium”and “Apostolus”)?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . p. 28§ 3. Why does the New Testament contain Four Gospels and not Oneo n l y ? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . p. 38§ 4. Why has only one Apocalypse been able to keep its place in the NewTestament? Why not several—or none at all?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . p. 44§ 5. Was the New Testament created consciously? and how did theChurches arrive at one common New Testament?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . p. 49II. The Consequences of the Creation of the New Testament. . . . . . . . . p. 57§ 1. The New Testament immediately emancipated itself from the conditionsof its origin, and claimed to be regarded as simply a gift of the Holy Spirit.It held an independent position side by side with the Rule of Faith; it atonce began to influence the development of doctrine, and it became inprinciple the final court of appeal for the Christian life. . . . . . . . . . . . . p. 57§ 2. The New Testament has added to the Revelation in history a secondwritten proclamation of this Revelation, and has given it a position ofsuperior authority. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . p. 59§ 3. The New Testament definitely protected the Old Testament as a bookof the Church, but thrust it into a subordinate position and thus introduceda wholesome complication into the conception of the Canon ofScripture. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . p. 61§ 4. The New Testament has preserved for us the most valuable portionof primitive Christian literature; yet at the same time it delivered the rest ofthe earliest works to oblivion, and has limited the transmission of laterworks. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . p. 63iii

The Origin of the New TestamentAdolf Harnack§ 5. Though the New Testament brought to an end the production ofauthoritative Christian writings, yet it cleared the way for theological andalso for ordinary Christian literary activity. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . p. 65§ 6. The New Testament obscured the true origin and the historicalsignificance of the works which it contained, but on the other hand, byimpelling men to study them, it brought into existence certain conditionsfavourable to the critical treatment and correct interpretation of theseworks. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . p. 66§ 7. The New Testament checked the imaginative creation of events in thescheme of Salvation, whether freely or according to existing models; butit called forth or at least encouraged the intellectual creation of facts in thesphere of Theology, and of a Theological Mythology. . . . . . . . . . . . . p. 68§ 8. The New Testament helped to demark a special period of ChristianRevelation, and so in a certain sense to give Christians of later times aninferior status; yet it has kept alive the knowledge of the ideals and claimsof Primitive Christianity. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . p. 69§ 9. The New Testament promoted and completed the fatal identificationof the Word of the Lord and the Teaching of the Apostles; but, because itraised Pauline Christianity to a place of highest honour, it has introducedinto the history of the Church a ferment rich in blessing. . . . . . . . . . . p. 70§ 10. In the New Testament the Catholic Church forged for herself a newweapon with which to ward off all heresy as unchristian; but she has alsofound in it a court of control before which she has appeared everincreasingly in default. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . p. 72§ 11. The New Testament has hindered the natural impulse to give to thecontent of Religion a simple, clear, and logical expression, but, on the otherhand, it has preserved Christian doctrine from becoming a mere philosophyof Religion. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . p. 73Conclusion. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . p. 74Appendices. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . p. 76I. The Marcionite Prologues to the Pauline Epistles. . . . . . . . . . . . . . p. 76Appendix II. Forerunners and Rivals of the New Testament. . . . . . . . . p. 77Appendix III. The Beginnings of the Conception of an “InstrumentumNovissimum”; the Hope for the “Evangelium Æternum”; the Public Lection,and the quasi-Canonical Recognition, of the Stories of the Martyrs in theChurch. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . p. 85Appendix IV. The Use of the New Testament in the Carthaginian (andRoman) Church at the Time of Tertullian. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . p. 90Appendix V. “Instrumentum” (“Instrumenta”) as a Name for the Bible. . . . p. 97iv

The Origin of the New TestamentAdolf HarnackAppendix VI. A Short Statement and Criticism of theInvestigations into the Origin of the New Testament. .Indexes. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Index of Scripture References. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Greek Words and Phrases. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Latin Words and Phrases. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Index of Pages of the Print Edition. . . . . . . . . . . . .vResults of Zahn’s. . . . . . . . . . . . p. 101. . . . . . . . . . . . p. 107. . . . . . . . . . . . p. 107. . . . . . . . . . . . p. 108. . . . . . . . . . . . p. 110. . . . . . . . . . . . p. 118

The Origin of the New TestamentAdolf Harnackvi

The Origin of the New TestamentAdolf HarnackNEW TESTAMENT STUDIESVITHE ORIGIN OF THENEW TESTAMENTAND THEMOST IMPORTANT CONSEQUENCESOF THE NEW CREATIONBYADOLF VON HARNACKTRANSLATED BYTHE REV. J. R. WILKINSON, M.A.FORMERLY SCHOLAR OF WORCESTER COLLEGE, OXFORDAND RECTOR OF WINFORDPublished by Williams and Norgate, 1925iv

The Origin of the New TestamentPREFACEvviAdolf HarnackTHE purpose of the following pages will be fulfilled if they serve to forward and complete thework accomplished by the histories of the Canon of the New Testament that already exist. Thehistory of the New Testament is here only given up to the beginning of the third century; for at thattime the New Canon was firmly established both in idea and form, and it acquired all theconsequences of an unalterable entity. The changes which it still under-went, however importantthey were from the point of view of the extent and unification of the Canon, have had noconsequences worth mentioning in connection with the history of the Church and of dogma. It istherefore appropriate, in the interests of clear thought, to treat the history of the Canon of the NewTestament in two divisions; in the first division to describe the Origin of the New Testament, in thesecond its enlargement. Moreover, it is necessary—though this is a point that hitherto has beenseldom taken into account—that the consequences that at once resulted from the new creationshould receive due consideration as well as its causes and motives. For the origin of the NewTestament is not a problem in the history of literature like the origin of the separate books of theCanon, but a problem of the history of cultus and dogma in the Church.A. v. H.BERLIN, 22nd May 1914.CONTENTSINTRODUCTIONxvI. The Needs and Motive Forces that led to the Creation of the 1New TestamentThe five chief problems—§ 1. How did the Church arrive 4at a second authoritativeCanon in addition to theOld Testament?A. What motives led to the 6creation of the NewTestament?(1) Supreme reverence for thewords and teaching ofChrist (“The HolyScriptures and theLord”), p. 7. (2)Supreme reverence forthe history of Christ2

The Origin of the New TestamentAdolf Harnack(“The Holy Scripturesand the Gospel”)—thesynthesis of prophecyand fulfilment, p. 9. (3)The new Covenant andthe desire for afundamental document,p. 12. (4) Supremereverence for what wasorthodox and ancient(the motive of Catholicand Apostolic), p. 16.B. Whence came the authority 20necessary for such acreation?(1)viiiC.(1)Teachers from thebeginning that wereauthoritativeandinspired by the Spirit(“Apostles, Prophets,and Teachers”), p. 20.(2) The right of theassembled community toaccept or reject books, P.21. (3) The inwardauthorityofApostolic-Catholicwritings that asserteditself automatically, p.23.How did the New 25Testament, assumed tobe necessary in idea,comeintoactualexistence?The existence ofappropriate works, p. 26.(2) Public lection (alsoprivate), p. 26. (3) Theimportanceoftheexample of Marcion andtheGnostics(the3

The Origin of the New TestamentAdolf Harnackelement of compulsionin the creation of theNew Testament), p. 29.(4) The importance oftheMontanistcontroversy, especiallyfor the idea of theclosing of the newCanon, p. 34. The result;relation to the OldTestament;the“ecclesiasticalscriptures,” p. 40.§ 2. Why is it that the New 42Testament also containsother books beside theGospels, and appears asa compilation with twodivisions (“Evangelium”and “Apostolus”)?The New Testament had 42already taken up intoitselftheearliesttradition of the ChurchA. The Apostles became, in a 44certain sense, equivalentto Christ. Estimation ofSt Paul; importance ofthe Acts of the ApostlesixB. The attestation of the 53Revelation became asimportant as its content;even the Gospels comeunder the idea of theApostolic. The newdominant note of thecollection not “theLord,”but“theApostles”C. The importance of the 57Canon of Marcion andof the Gnostics also for4

The Origin of the New TestamentAdolf Harnackthe division into twoparts, especially for theprestige of the PaulineEpistles; their inwardand outward CatholicityThe Catholic Epistles and the 63Acts;thecentralimportance of the latterfor the structure of theNew Testament; theNew Testament in itscompletion a work ofreflection§ 3.Why does the New 68Testament contain fourGospels and not onlyone?The age and the significance 68of the canonical titles ofthe four GospelsThe time and place of the 71compilation(AsiaMinor)Tension between the Gospels 72and the compromise inthe acceptance of fourThenumber four not 74originally intended to befinal; against JülicherThe same motive that led to 80the“Apostolus”prevented the unificationof the four Gospels§ 4.Why has only one 83Apocalypse been able tokeep its place in the NewTestament? Why notseveral—or none at all?The Muratorian Fragment as 83starting-point5

The Origin of the New TestamentAdolf HarnackxThree Apocalypses originally 85in New TestamentThe expulsion of Prophecy 87and the sovereignty ofthe Apostolic in the NewTestamentHow was it that the break 90with Prophecy was notnecessarily felt as abreach with the past?The expulsion of the Petrine 91Apocalypse and ofHermasThe dangerous situation of 92theJohannineApocalypse§ 5. Was the New Testament 94created consciously? andhow did the Churchesarrive at one commonNew Testament?The New Testament must 95have been foundedbetween A.D. 160 and180, and in idea finallycompleted between A.D.180 and 200Structure, choice of books, 96and the titles of thecollection show that inthe last resort it is aconscious creationThe immediate forerunner of 100the New Testament is tobe sought in theChurches lying on theline between WesternAsia Minor and RomeThe fixing of the Canon as a 103collectionofApostolic-Catholic6

The Origin of the New TestamentAdolf Harnackworks took place inRomeThetestimony of the 106Muratorian Canon to thisfactSummary of results. The 109witness of Clement ofAlexandriatotheimmediate forerunner ofthe New TestamentThe reception of the Now 111Testament, and itscompletioninacollectionoftwenty-seven books atAlexandriaThe victory of this New 112TestamentII. The Consequences of the Creation of the New Testament115xi§ 1.The New Testament 116i m m e d i a t e l yemancipated itself fromthe conditions of itsorigin and claimed to beregarded simply as a giftof the Holy Spirit. It heldan independent positionside by side with theRule of Faith, it at oncebegan to influence thedevelopment of doctrine,and it became inprinciple the final courtof appeal for theChristian life§ 2. The New Testament has 121added to the Revelationin History a secondwritten proclamation ofthis Revelation, and has7

The Origin of the New TestamentAdolf Harnackgiven it a position ofsuperior authority§ 3.The New Testament 125definitely protected theOld Testament as a bookof the Church, but thrustit into a subordinateposition,andthusintroduced a wholesomecomplication into theconception of the Canonof Scripture§ 4. The New Testament has 131preserved for us the mostvaluable portion ofprimitiveChristianliterature, yet at the sametime it delivered the restof the earliest works tooblivion and has limitedthe transmission of laterworks§ 5. Though the New Testament 138brought to an end theproductionofauthoritative Christianwritings, yet it clearedthe way for theologicaland also for ordinaryChristian literary activity§ 6.xiiThe New Testament 140obscured the true originandthehistoricalsignificance of the workswhich it contained, buton the other hand, byimpelling men to studythem, it brought intoexistencecertainconditions favourable tothe critical treatment and8

The Origin of the New TestamentAdolf Harnackcorrect interpretation ofthese works§ 7.The New Testament 144checked the imaginativecreation of events in thescheme of Salvationwhetherfreelyoraccording to existingmodels, but it calledforth, or at leastencouragedtheintellectual creation offacts in the sphere oftheology and of atheological mythology§ 8. The New Testament helped 147to demark a specialperiod of ChristianRevelation, and so in acertain sense to giveChristians of later timesan inferior status; yet itkept alive the ideals andclaims of primitiveChristianity§ 9.The New Testament 150promoted and completedthe fatal identification ofthe Word of the Lordand the Teaching of theApostles; but because ItraisedPaulineChristianity to a place ofhigh honour, it hasintroduced into thehistory of the Church aferment rich in blessing§ 10. In the New Testament the 154Catholic Church forgedfor herself a new weaponwith which to ward offallheresyas9

The Origin of the New TestamentAdolf Harnackun-Christian, but she hasalso found in it a courtof control before whichshe has appeared everincreasingly in defaultxiii§ 11. The New Testament has 158hindered the naturalimpulse to give to thecontent of Religionsimple, clear, and logicalexpression, but on theother hand it haspreservedChristiandoctrine from becominga mere philosophy ofReligionConclusion162APPENDICESI.The Marcionite Prologues to the 165Pauline EpistlesII.Forerunners and Rivals of the 169New TestamentIII.TheBeginningsofthe 184Conception of an “InstrumentumNovissimum,” the Hope for the“Evangelium Æternum”; thePublic Lection, and thequasi-Canonical Recognition ofthe Stories of the Martyrs in theChurchIV.The Use of the New Testament 196in the Carthaginian (and Roman)Church at the Time of TertullianV.“Instrumentum” (“Instrumenta”) 209as a Name for the BibleVI.A Short Statement and Criticism 218of the Results of Zahn’sInvestigations into the Origin ofthe New Testamentxv10

The Origin of the New TestamentAdolf HarnackINTRODUCTIONxviTHE collection of writings Apostolic and Catholic (the New Testament), the Apostolic Rule ofFaith, the Apostolic character assigned to the Bishops (dependent upon succession) mark the chiefresults of the inner development of Church history during the first two centuries. This conclusion,as modern text-books of the history of Church and dogma show, is to-day almost universallyaccepted. And yet, with all our excellent treatises on the history of the origin of the New Testament,and in spite of the far-reaching agreement of our scholars in just this province of research, it is stillnot superfluous to show how clearly and comprehensively the history of the Primitive Church hasmanifested itself in the leading principle, in the creation and compilation of the New Testament,and how vast and decisive, and, on the other hand, how various and even contradictory were theconsequences of its appearance.1 Moreover, the question whether and to what extent the NewTestament was consciously created has not yet been cleared up. Lastly, though it is firmly establishedthat this collection of inspired writings is a remainder-product—for once upon a time everythingthat a Christian wrote for edification counted as inspired—yet there is still need of more rigorousinvestigation of the circumstances which necessarily led to restriction and choice.14In my Lehrbuch der Dogmengeschichte (1 , S. 372-399) I have given a sketch of the history of the origin of the New Testamentfrom the standpoint of the history of Dogma. The object of the following pages is to give a more comprehensive and clear-cutdiscussion of the chief points in the story of the development, and of the motive forces at work, in connection with the generalhistory of the Church, and to state more forcibly the consequences of the creation of the New Testament.11

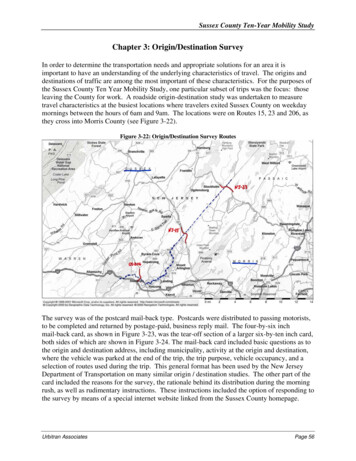

The Origin of the New TestamentAdolf HarnackTHE ORIGIN OF THE NEW TESTAMENTI1THE NEEDS AND MOTIVE FORCES THAT LED TO THE CREATION OF THE NEW TESTAMENTIF the trained observer surveys merely the Title and the Table of Contents of the New Testament,whether in its present form or in the older and shorter form of the close of the second century, andif he adopts the viewpoint of the Apostolic Age, he is faced by at least five great historical problems.The GospelThe Books of the New Testament(or the New Testament).{according to Matthewaccording to Mark.according to Luke.according to John.The Apostolus{The Acts of the Apostles.Thirteen Epistles of Paul.The Epistle of Jude.The lst and 2nd Epistles ofJohn.2The Apostolus{(The 1st Epistle of Peter).The Revelation of John.2(The Revelation of Peter).(The Shephard of Hermas).323These two epistles have the testimony of the Murat. Fragment and of the Corpus Cypr. (In Tert., De Pudic., “in primore” is tobe read in place of “in priore epistola [Joannis)”).The three bracketed works have a special history. In regard to 1 Peter it is not quite certain whether it belongs to the earliestform of the New Testament. The two Apocalypses may indeed be assigned to the most ancient form, but they were objected toat once, and this in the community of Rome, which, as we shall show, was probably the very birthplace of the New Testament.The opposition to the Revelation of Peter was at first the weaker of the two, but it very soon and completely attained it object,while in the case of the Shepherd of Hermas it was strong from the beginning but did not find complete success until later. Inthe earliest (Roman) list of Canonical Scriptures which we possess, mention is also made of a “Wisdom” of Solomon which weare told was composed by Christian admirers of Solomon. Probably “Jesus Sirach” is meant, which was also called “Ecclesiasticus.”We have here a singular phenomenon which we cannot quite comprehend. From the standpoint of the close of the second centuryno special importance need be assigned to the order of the Gospels nor to the position of the Catholic Epistles (Philastr., 88:“Septem epistulæ Actibus Apostolorum conjunctæ sunt”) which could also be placed before the Pauline Epistles. Only theprecedence of the Gospels before all the rest of the writings and the placing of the Acts of the Apostles at the head of the seconddivision in idea and soon in actual practice (Murat. Fragment, see also Irenæus and Tertullian) are firmly established. But itwould be a mistake to imagine that at the end of the second century absolutely no interest was taken in the question of the number12

The Origin of the New TestamentAdolf HarnackThe five problems are these:—31. What is the reason and how did it come about that a second authoritative collection of booksarose among Christians? Why were they not satisfied with the Old Testament, or with a Christianedition of the Old Testament, or—if they must needs have a new collection —why did they notreject the old? Why did they take upon themselves the burden and complication of two collections?Finally, when did the idea of a fixed second collection first appear?2. Why does the New Testament contain other works in addition to the Gospels, and thus appearas a whole with two divisions (Gospel and Apostle)?3. Why does the New Testament contain four gospels and not one only?4. Why could only one “Revelation” keep its place in the New Testament? Why not several ornone at all?5. Was the New Testament created consciously? How did the Churches arrive at one commonNew Testament, seeing that the individual communities, or provincial Churches, were independent,and that the Church was one only in idea?From the standpoint of the Apostolic Epoch these five questions appear as just so many enormousparadoxes so long as one does not go deeply beneath the surface of events as they developed. Ipurpose to attempt a brief discussion of these questions; and it would be perhaps much to the pointif future works on the history of the Canon of the New Testament started in the same way.§ 1. How did the Church arrive at a second authoritative Canon in addition to the Old Testament?4From the standpoint of the Apostolic Epoch it would be perfectly intelligible if the Church, inregard to written authorities, had decided to be satisfied with the possession of the Old Testament.I need not trouble to prove this. We should, however, have been to a certain extent prepared if, astime went on, the Church had added some other writings to this book to which it held fast. Indeed,in the first century, even among the Jews, the Old Testament was not yet quite rigidly closed, itsthird division was still in a somewhat fluid condition, and, above all, in the Dispersion, among theGreek-speaking Jews, side by side with the Scriptures of the Palestinian collection, there were incirculation numerous sacred writings in Greek of which a considerable number became graduallyand quite naturally attached to the authoritative collection. It would therefore have been in no sensesurprising, nor would it have been regarded as extraordinary, if from the Christian side some newedifying works had been added to this collection. This actually happened here and there withApocalypses; indeed, attempts were even made to smuggle new chapters and verses into some ofand order of canonical writings. The contrary is proved by the petition of the brother Onesimus to Melito, Bishop of Sardis, thathe would give him information concerning the number and order of the books of the Old Testament. Melito responded to thisrequest, and by a method of counting of his own set the number at twenty-one (Euseb., H.E., iv. 26, 13).13

The Origin of the New Testament56Adolf Harnackthe ancient books of the Canon.4 In this fashion Christians might have proceeded in yet bolder style,without doing anything unusual, and so might have been able to satisfy requirements which werenot met, or not completely met, by the Old Testament. Lastly, judging from the standpoint of theApostolic Age, we should not have been surprised if in the near future the Old Testament had beenrejected or set aside by the Gentile Churches. When the word had gone forth that one should knownothing else than Christ Crucified and Risen, when it was taught that the Law was abolished andthat all had become new, the step was very near to recognise the Gospel of Christ, and nothing else.“I believe nothing that I do not find in the Gospel” (Ignat., Phil., 8)—what object then was servedby the Old Testament? That the Apostle who taught all this nevertheless himself accepted the OldTestament offered no special difficulty. Gentile Christians knew very well that the Apostle, whoto Jews became a Jew, for his own person and out of regard to the Jews, had clung to many thingsthat were not meant to be accepted by others or need no longer be accepted. For all these possibilities(the Old Testament alone; an enriched Old Testament; no Old Testament) we should thus havebeen prepared; but we should have been absolutely unprepared for that which actually happened—asecond authoritative collection. How did this come about? It is true indeed that the fact that an OldTestament existed had the most important part in the suggestion and creation of a New Testament;and yet for decades of years the Old Testament was the greatest hindrance to such a creation, moreespecially because the Old Testament in a very complete and masterly way was subjected to Christianinterpretation,5 and so Christians already possessed in it a foundation document for that new thingwhich they had experienced. Still, far down beneath the movements of the time, a more surepreparation was being made for that which was to come, namely the New Testament, than for allthe other possibilities. These had their strength in forces which lay on the surface; but under thesurface a new spirit was working from the beginning, and was striving to come to light.Here three questions present themselves: (A) What motives led to the creation of the NewTestament? (B) Whence came the authority that was necessary for such a creation? (C) Supposingthe necessity of a New Testament, how did it actually come into being?(A) Here a series of motives increasing in importance were at work; but it was the last of thesethat demanded a new written authority side by side with the Old Testament (and this withoutabandonment of the same).7(1) The earliest motive force, one that had been at work from the beginning of the ApostolicAge, was the supreme reverence in which the words and teaching of Christ Jesus were held. I havepurposely used the expression “supreme reverence,” for in the ideas of those days inspiration andauthority had their degrees. Not only were the spirits of the prophets subject to the prophets, butthere were recognised degrees of higher and highest in their utterances. Now there can be no doubtthat for the circle of disciples the Word of Jesus represented the highest degree. He Himself hadoften introduced His message with the words “I am come” (i.e. to do something which had not yet45See my Altchristl. Lit.-Gesch., 1, S. 849 ff.; ii. 1, S. 560–589; Texte u. Unters., Bd. 39, Hft. 1, S. 69 ff. That round about the yearA.D. 200 Tertullian wished to add Enoch to the Old Testament is well known, and the reasons he gives are very instructive. SeeSitzungsber., 1914, S. 310 f.St Paul himself offered a rich collection of such Christian interpretations, although he, as a rule, allowed to the Law its literalsense.14

The Origin of the New Testament89Adolf Harnackbeen done), or, “But I say unto you” (in opposition to something that had been hitherto said). Thisclaim received its complete recognition among the disciples in the unswerving conviction that thewords and directions of Jesus formed the supreme rule of life. Thus side by side with the writingsof the Old Testament appeared the Word of “the Lord,” and not only so, but in the formula γραφαὶκαὶ ὁ κύριος6 the two terms were not only of equal authority, but the second unwritten term receiveda stronger accent than the first that had literary form. We may therefore say that in this formula wehave the nucleus of the New Testament. But even in the Apostolic Age and among the Palestiniancommunities it had become interchangeable with the formula αἱ γραφαὶ καὶ τὸ εὐαγγέλιον7 for inthe “Good News” was comprised what the Messiah had said, taught, and revealed.8 These twoalmost identical formulæ, though they do not as yet distinguish the followers of Jesus from idealJudaism, nevertheless mark a breach with Judaism as it actually existed.9(2) The second motive, manifested with peculiar force in St Paul, but by no means exclusivelyin him, is the interest in the Death and Resurrection of the Messiah Jesus, an interest whichnecessarily led to the assigning of supreme importance to, and to the crystallisation of the traditionof, the critical moments of His history. Under the influence of this motive “the Gospel” came tomean the good news of the Divine plan of Salvation, proclaimed by the prophets, and now6789(The Scriptures and the Lord.) I cannot be persuaded that “the Lord” as a title of Jesus was first conceived on Gentile-Christiansoil. The idea of “Messiah” simply includes that of “Lord.” The formula “The Scriptures and the Lord” has manifold attestationdirect as well as indirect in the Apostolic and post-Apostolic epoch.(The Scriptures and the Gospel.)It is a waste of time to discuss which of the two formulæ, αἱ γραφαὶ καὶ ὁ κύριος or αἱ γραφαὶ καὶ τὸ εὐαγγέλιον, is the earlie

Origin of the New Testament, in the second its . enlargement. Moreover, it is necessary—though this is a point that hitherto has been. vi. seldom taken into account—that the consequences that at once resulted from the new creation should receive due consideration as