Transcription

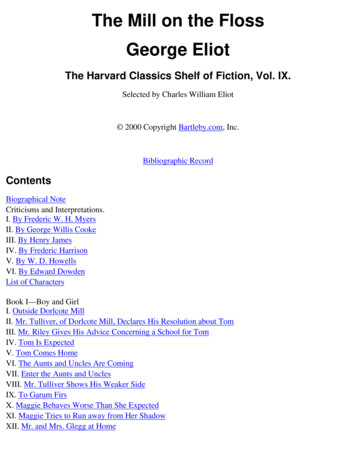

The Mill on the FlossGeorge EliotThe Harvard Classics Shelf of Fiction, Vol. IX.Selected by Charles William Eliot 2000 Copyright Bartleby.com, Inc.Bibliographic RecordContentsBiographical NoteCriticisms and Interpretations.I. By Frederic W. H. MyersII. By George Willis CookeIII. By Henry JamesIV. By Frederic HarrisonV. By W. D. HowellsVI. By Edward DowdenList of CharactersBook I—Boy and GirlI. Outside Dorlcote MillII. Mr. Tulliver, of Dorlcote Mill, Declares His Resolution about TomIII. Mr. Riley Gives His Advice Concerning a School for TomIV. Tom Is ExpectedV. Tom Comes HomeVI. The Aunts and Uncles Are ComingVII. Enter the Aunts and UnclesVIII. Mr. Tulliver Shows His Weaker SideIX. To Garum FirsX. Maggie Behaves Worse Than She ExpectedXI. Maggie Tries to Run away from Her ShadowXII. Mr. and Mrs. Glegg at Home

XIII. Mr. Tulliver Further Entangles the Skein of LifeBook II—School-TimeI. Tom’s “First Half”II. The Christmas HolidaysIII. The New SchoolfellowIV. “The Young Idea”V. Maggie’s Second VisitVI. A Love-SceneVII. The Golden Gates Are PassedBook III—The DownfallI. What Had Happened at HomeII. Mrs. Tulliver’s Teraphim, or Household GodsIII. The Family CouncilIV. A Vanishing GleamV. Tom Applies His Knife to the OysterVI. Tending to Refute the Popular Prejudice against the Present of a Pocket-KnifeVII. How a Hen Takes to StratagemVIII. Daylight on the WreckIX. An Item Added to the Family RegisterBook IV—The Valley of HumiliationI. A Variation of Protestantism Unknown to BossuetII. The Torn Nest Is Pierced by the ThornsIII. A Voice from the PastBook V—Wheat and TaresI. In the Red DeepsII. Aunt Glegg Learns the Breadth of Bob’s ThumbIII. The Wavering BalanceIV. Another Love-SceneV. The Cloven TreeVI. The Hard-Won TriumphVII. A Day of ReckoningBook VI—The Great TemptationI. A Duet in ParadiseII. First ImpressionsIII. Confidential MomentsIV. Brother and SisterV. Showing That Tom Had Opened the Oyster

VI. Illustrating the Laws of AttractionVII. Philip Re-entersVIII. Wakem in a New LightIX. Charity in Full-DressX. The Spell Seems BrokenXI. In the LaneXII. A Family PartyXIII. Borne Along by the TideXIV. WakingBook VII—The Final RescueI. The Return to the MillII. St. Ogg’s Passes JudgmentIII. Showing That Old Acquaintances Are Capable of Surprising UsIV. Maggie and LucyV. The Last ConflictConclusionBiographical NoteMARY ANN (or Marian) EVANS was born at Arbury farm in the parish of Chilvers Coton,Warwickshire, England, on November 22, 1819. Her father was agent for the Newdigate estates inWarwickshire and Derbyshire, and her mother was his second wife. Mary Ann, the youngest of fivechildren, went to school in the neighbouring towns of Attleborough, Nuneaton, and Coventry, and earlyshowed exceptional intellectual as well as musical ability. Though she left school at sixteen, shecontinued her studies, at times under visiting masters, until she became one of the most accomplishedwomen of her time. A picture of her youth, substantially true though intentionally altered in details, is tobe found in the early years of the heroine of “The Mill on the Floss.” In some respects, therefore, thisbook is to George Eliot what “David Copperfield” is to Dickens and “Pendennis” to Thackeray.From the time of her mother’s death in 1835 until her father’s in 1849 she kept house, and provedherself an excellent manager. In 1841 she and her father moved to Coventry where she came in contactwith society of an intellectual type new in her experience. One result of this and of the ever-wideningrange of her reading was the loss of the intense if somewhat narrow evangelical faith she had hithertoheld; but she retained, and later exhibited in her novels, a sympathetic understanding of religioussentiments which she no longer shared. While still at Coventry she translated from the German Strauss’s“Life of Jesus,” published in 1846.On her father’s death she paid her first visit to the Continent, settling for some time at Geneva, andreturned to make her home for a period with her friends, the Brays, at Coventry. An appointment asassistant editor of the “Westminster Review” took her to London in 1851, and while still occupying thisposition she translated Feuerbach’s “Essence of Christianity” (1854). Her work on the review was of ahigh quality, and the associations it brought led to her acquaintance with the leaders of progressive

thought in England, such as Carlyle, Herbert Spencer, and Harriet Martineau. Among these was abrilliant and versatile writer George Henry Lewes, whose range of knowledge and conversational powersmade him a notable figure in intellectual circles in London. He had been in business and had studiedmedicine; had lived much in France and Germany and was abreast of continental thought; had been uponthe stage and had lectured on philosophy; had produced a play, two novels, and articles without number.He is best known now for his “Biographical History of Philosophy” and his “Life of Goethe.” Lewes wasmarried, but his wife had given him what he considered grounds for considering his marriage void,though a legal divorce was not possible. Miss Evans shared Milton’s opinions on marriage, and at thecost of temporary social isolation she formed an unconventional relation with Lewes and regarded herselfhenceforth as his wife. The union, as far as the mutual relation of the parties was concerned, provedextremely happy, and Lewes’s influence proved highly favorable to the discovery and development ofthe hitherto unsuspected talent of the novelist. It was at his suggestion that she, after a second visit to theContinent, began “Amos Barton,” which with “Janet’s Repentance” and “Mr. Gilfil’s Love Story”appeared in “Black-wood’s Magazine,” the three being published in book form in 1858 as “Scenes fromClerical Life,” by “George Eliot.” The pen name, by which to-day she is universally known, was formedfrom her husband’s first name, and “Eliot,” chosen as “a good, mouth-filling, easily pronounced word.”These stories, which in some respects she never surpassed, attracted only a moderate amount of attention,but competent judges, like Dickens, were enthusiastic. More general popularity was won by “AdamBede” (1859), and her success, far beyond her expectations, gave her confidence and encouragement.“The Mill on the Floss,” followed in 1860 and “Silas Marner” in 1861, completing what is regarded asher first literary period, and establishing her securely in the first rank of the novelists of the time.The next period began with “Romola,” an elaborate picture of Florentine life in the Renaissance, theresult of two visits to Italy and a vast amount of historical study. Opinion has always been divided as tothe merits of this work, which, with all its richness of historical detail and its brilliancy as a picture of thetime, fails to make its characters (with one exception) as convincing as the simpler English people of theearlier books. “Felix Holt, the Radical,” which deals with a political situation in England, was lesssuccessful; and for a time she turned to drama and verse-writing in “The Spanish Gypsy” and “TheLegend of Jubal.”Her next book, however, “Middlemarch” (1872), showed a return of her greatest powers, and in itssuperb treatment of a whole section of English provincial life placed her with Tolstoi and Balzac.“Daniel Deronda,” which followed, has high distinction, but fails to show the same complete mastery,and has never been among her most popular books.The death of Lewes in 1878 proved an overwhelming shock, and George Eliot wrote no more. In 1880she married Mr. J. W. Cross, a friend of some ten years’ standing, who had been a great support to her inher prostration; but though she seemed to regain strength for a time, she died on December 3 of the sameyear.George Eliot’s whole life and character were permeated by moral passion. Cut off from the usual outletsfor religious emotion by the rationalism to which she adhered from the early years at Coventry, shepoured out her whole soul at the shrine of duty, and her novels reveal an absorbing interest in theproblems of conduct. The danger that they might become mere disguised tracts was averted by herclear-sightedness as to the method of art. She knew that her business as a writer of fiction was to paintpictures of life, not construct diagrams to demonstrate moral precepts. Occasionally, as in “DanielDeronda,” she comes dangerously near allowing the human interest to be overshadowed by the

“purpose,” but in her more successful books, especially those dealing with the English provincial lifeamidst which she had grown up, she achieves her moral aim by the legitimate method of enlarging thereader’s sympathies through enlisting them on behalf of a large number of real creationsAmong these pictures of the Midlands as she had known them in her childhood, “The Mill on theFloss,” though less well-proportioned than “Adam Bede” or “Silas Marner,” stands out by virtue of theintensity with which the main characters and situations are conceived and portrayed. Maggie Tulliver,partly, no doubt, because of the autobiographical element, is as living and appealing a heroine as is to befound in English fiction, and nothing can surpass the truth and poignancy of the treatment of her relationsto Tom. It is worth noting that Isaac Evans was estranged from his sister by her marriage with Lewes,and was reconciled only a few months before she died. Far though George Eliot is from depending forher success upon literal copying of actual persons or events, it yet seems to be true of her, as of so manyof her rivals, that she did her most vital work in the handling of themes and emotions that had beenilluminated by her own experience.W. A. N.Criticisms and Interpretations.I. By Frederic W. H. MyersEVERYTHING in her aspect and presence was in keeping with the bent of her soul. The deeply linedface, the too marked and massive features, were united with an air of delicate refinement, which in oneway was the more impressive because it seemed to proceed so entirely from within. Nay, the inwardbeauty would sometimes quite transform the external harshness; there would be moments when the thinhands that entwined themselves in their eagerness, the earnest figure that bowed forward to speak andhear, the deep gaze moving from one face to another with a grave appeal—all these seemed thetransparent symbols that showed the presence of a wise, benignant soul. But it was the voice which bestrevealed her, a voice whose subdued intensity and tremulous richness seemed to environ her utteredwords with the mystery of a world of feeling that must remain untold. “Speech,” says her Don Silva toFedalma, in The Spanish Gypsy,“Speech is but broken light upon the depthOf the unspoken; even your loved wordsFloat in the larger meaning of your voiceAs something dimmer.”And then again, when in moments of more intimate converse some current of emotion would setstrongly through her soul, when she would raise her head in unconscious absorption and look out into theunseen, her expression was not one to be soon forgotten. It had not, indeed, the serene felicity of souls towhose childlike confidence all heaven and earth are fair. Rather it was the look (if I may use a Platonicphrase) of a strenuous Demiurge, of a soul on which high tasks are laid, and which finds in theiraccomplishment its only imagination of joy.“It was her thought she saw; the presence fairOf unachieved achievement, the high task,The mighty unborn spirit that doth askWith irresistible cry for blood and breathTill feeding its great life we sink in death.”

I do not wish to exaggerate. The subject of these pages would not tolerate any words which seemed topresent her as an ideal type. For, as her aspect had greatness, but not beauty, so too her spirit had moraldignity but not saintly holiness. A loftier potency may sometimes have been given to some highlyfavored women in whom the graces of heaven and earth have met; mowing through all life’s seasonswith a majesty which can feel no decay; affording by her very presence and benediction an earnest of thesupernal world. And so, too, on that thought-worn brow there was visible the authority of sorrow, butscarcely its consecration. A deeper pathos may sometimes have breathed from the unconscious heroismof some childlike soul.It is perhaps by thus dwelling on the last touches which this high nature was dimly felt to lack—somearoma of hope, some felicity of virtue—that we can best recognize the greatness of her actualachievement, of her practical working-out of the fundamental dogma of the so-called Religion ofHumanity—the expansion, namely, of the sense of human fellowship into an impulse strong enough tocompel us to live for others, even though it be beneath the oncoming shadow of an endless night. For sheheld that there was so little chance of man’s immortality that it was a grievous error to flatter him withsuch a belief; a grievous error at least to distract him by promises of future recompense from the urgentand obvious motives of well-doing—our love and pity for our fellow men. She repelled “that impietytoward the present and the visible, which flies for its motives, its sanctities, and its religion to the remote,the vague, and the unknown,” as contrasted with “that genuine love which cherishes things in proportionto their nearness, and feels its reverence grow in proportion to the intimacy of its knowledge.” Thesewords are from the essay on “Worldliness and Other-Worldliness,” which has been alluded to, and whichcontains a forcible condemnation of the view—advanced by the poet Young in its utmostcrudity—according to which the reason for virtue is simply the prospect of being rewarded for ithereafter. So far as moral action is dependent on that belief, so far, she urges, “the emotion whichprompts it is not truly moral—is still in the stage of egoism, and has not yet attained the higherdevelopment of sympathy.” And she adds to this a moving argument, which in after life was often on herlips and in her heart. “It is conceivable,” she says, “that in some minds the deep pathos lying in thethought of human mortality—that we are here for a little while and then vanish away, that this earthly lifeis all that is given to our loved ones and to our many suffering fellow men—lies nearer the fountains ofmoral emotion than the conception of extended existence.”It was, indeed, above all things, this sadness with which she contemplated the lot of dying men whichgave to her convictions an air of reality far more impressive than the rhetorical satisfaction which issometimes expressed at the prospect of individual annihilation. George Eliot recognized the terribleprobability that, for creatures with no future to look to, advance in spirituality may oftenest be butadvance in pain; she saw the somber reason of that grim plan which suggests that the world’s lifelongstruggle might best be ended—not, indeed, by individual desertions, but by the moving off of the wholegreat army from the field of its unequal war—by the simultaneous suicide of all the race of man. Butsince this could not be; since that race was a united army only in metaphor—was, in truth, a never-endinghost“Whose rear lay wrapt in night, while breaking dawnRoused the broad front, and called the battle on,”she held that it befits us neither to praise the sum of things nor to rebel in vain, but to take care only thatour brothers’ lot may be less grievous to them in that we have lived. Even so, to borrow a simile from M.Renan, the emperor who summed up his view of life in the words Nil expedit, gave none the less to his

legions as his last night’s watchword, Laboremus.This stoic lesson she would enforce in tones which covered a wide range of feeling, from the graveexhortation which disdained to appeal to aught save an answering sense of right, to the tender wordswhich offered the blessedness of self-forgetting fellowship as the guerdon won by the mourner’s pain.I remember how, at Cambridge, I walked with her once in the Fellows’ Garden of Trinity, on anevening of rainy May; and she, stirred somewhat beyond her wont, and taking as her text the three wordswhich have been used so often as the inspiring trumpet-calls of men—the words God, Immortality,Duty—pronounced, with terrible earnestness, how inconceivable was the first, how unbelievable thesecond, and yet how peremptory and absolute the third. Never perhaps, have sterner accents affirmed thesovereignty of impersonal and unrecompensing Law. I listened, and night fell; her grave, majesticcountenance turned toward me like a sibyl’s in the gloom; it was as though she withdrew from my grasp,one by one, the two scrolls of promise, and left me the third scroll only, awful with inevitable fates. Andwhen we stood at length and parted amid that columnar circuit of the forest trees, beneath the lasttwilight of starless skies, I seemed to be gazing, like Titus at Jerusalem, on vacant seats and emptyhalls—on a sanctuary with no Presence to hallow it, and heaven left lonely of a God.—From “GeorgeEliot,” in the “Century Magazine” (November, 1881).Criticisms and Interpretations.II. By George Willis CookeIN literature, the new method as developed in recent years consists in an application of psychology to allthe problems of man’s nature. George Eliot’s intimate association with the leaders of the scientificmovement in England, naturally turned her mind into sympathy with their work, and made her desirousof doing in literature what they were doing in science. In the special department of physiologicalpsychology, no one did more than George Henry Lewes, and her whole heart went out in genuineappreciation of his work. He studied the mind as a function of the brain, as being developed with thebody, as the result of inherited conditions, as intimately dependent on its environment. Here was a newconception of man, which regarded him as the last product of nature, considered as an organic whole.This conception George Eliot everywhere applied in her studies of life and character. She studied man asthe product of his environment, not as a being who exists above circumstances and material conditions.“In the eyes of the psychologist,” says Mr. James Sully, “the works of George Eliot must always possessa high value by reason of their large scientific insight into character and life.” This value consists, as heindicates, in the fact that she interprets the inner personality as it is understood by the scientific student ofhuman nature. She describes those obscure moral tendencies, nascent forces, and undertones of feelingand thought, which enter so much into life. She lays much stress on the subconscious mental life, thedomain of vague emotion and rapidly fugitive thought.The aim of the psychologic method is to interpret man from within, in his motives and impulses. Itendeavors to show why he acts, and it unfolds the subtler elements of his character. This method GeorgeEliot uses in connection with her evolutionary philosophy, and uses it for the purpose of showing thatman is a product of hereditary conditions, that he has been shaped into his life of the emotions andsentiments by the influence of tradition. The psychologic method may be applied, however, withoutconnection with the positive or evolutionary philosophy. The mind may be regarded as a distinct forceand power, exercised within social and material limits, and capable of being studied in all its inner

motives and impulses. Yet in her mental inquiries George Eliot did not regard man as an eternal soul inthe process of development by divine methods, but as the inheritor of the past, moulded by everysurrounding circumstance, and as the creature of the present. Instead of regarding man as sub specieeternitatis, she regarded him as an animal who has through feeling and social development come to knowthat he cannot exist beyond the present. This limitation of his nature affected her workthroughout.—From “George Eliot, a Critical Study” (1883).Criticisms and Interpretations.III. By Henry JamesSHE accepted the great obligations which to her mind belonged to a person who had the ear of thepublic, and her whole effort thenceforth was highly to respond to them—to respond to them by teaching,by vivid moral illustration, and even by direct exhortation. It is striking that from the first her conceptionof the novelist’s task is never in the least as the game of art. The most interesting passage in Mr. Cross’svolume is, to my sense, a simple sentence in a short entry in her journal in the year 1859, just after shehad finished the first volume of “The Mill on the Floss” (the original title of which, by the way, had been“Sister Maggie”): “We have just finished reading aloud Père Goriot, a hateful book.” That Balzac’smasterpiece should have elicited from her only this remark, at a time, too, when her mind might havebeen opened to it by her own activity of composition, is significant of so many things that the few wordsare, in the whole Life, those I should have been most sorry to lose. Of course they are not all GeorgeEliot would have had to say about Balzac, if some other occasion than a simple jotting in a diary hadpresented itself. Still, what even a jotting may not have said after a first perusal of “Le Père Goriot” iseloquent; it illuminates the author’s general attitude with regard to the novel, which, for her, was notprimarily a picture of life, capable of deriving a high value from its form, but a moralized fable, the lastword of a philosophy endeavoring to teach by example.This is a very noble and defensible view, and one must speak respectfully of any theory of work whichwould produce such fruit as “Romola” and “Middlemarch.” But it testifies to that side of George Eliot’snature which was weakest—the absence of free æsthetic life (I venture this remark in the face of apassage quoted from one of her letters in Mr. Cross’s third volume); it gives the hand, as it were, toseveral other instances that may be found in the same pages. “My function is that of the æsthetic, not thedoctrinal teacher; the rousing of the nobler emotions, which make mankind desire the social right, not theprescribing of special measures, concerning which the artistic mind, however strongly moved by socialsympathy, is often not the best judge.” That is the passage referred to in my parenthetic allusion, and it isa good general description of the manner in which George Eliot may be said to have acted on hergeneration; but the “artistic mind,” the possession of which it implies, existed in her with limitationsremarkable in a writer whose imagination was so rich. We feel in her, always, that she proceeds from theabstract to the concrete; that her figures and situations are evolved, as the phrase is, from her moralconsciousness, and are only indirectly the products of observations. They are deeply studied andelaborately justified, but they are not seen in the irresponsible plastic way. The world was, first andforemost, for George Eliot, the moral, the intellectual world; the personal spectacle came after; andlovingly, humanly, as she regarded it, we constantly feel that she cares for the things she finds in it onlyso far as they are types. The philosophic door is always open, on her stage, and we are aware that thesomewhat cooling draught of ethical purpose draws across it. This constitutes half the beauty of herwork; the constant reference to ideas may be an excellent source of one kind of reality—for, after all, thesecret of seeing a thing well is not necessarily that you see nothing else. Her preoccupation with the

universe helped to make her characters strike you as also belonging to it; it raised the roof, widened thearea, of her æsthetic structure. Nothing is finer, in her genius, than the combination of her love of generaltruth and love of the special case; without this, indeed, we should not have heard of her as a novelist, forthe passion of the special case is surely the basis of the story-teller’s art. All the same, that little sign ofall that Balzac failed to suggest to her showed at what perils the special case got itself considered.—From“George Eliot’s Life,” in the “Atlantic Monthly” (May, 1885).Criticisms and Interpretations.IV. By Frederic HarrisonAFTER all that has been written about George Eliot’s place as an artist, it may be doubted if attentionhas been properly directed to her one unique quality. Whatever be her rank amongst the creators ofromance (and perhaps the tendency now is to place it too high rather than too low), there can be no doubtthat she stands entirely apart and above all writers of fiction, at any rate in England, by her philosophicpower and general mental calibre. No other English novelist has ever stood in the foremost rank of thethinkers of his time. Or to put it the other way, no English thinker of the higher quality has ever usedromance as an instrument of thought. Our greatest novelists could not be named beside her off the fieldof novel-writing. Though some of them have been men of wide reading, and even of special learning,they had none of them pretensions to the best philosophy and science of their age. Fielding andGoldsmith, Scott and Thackeray, with all their inexhaustible fertility of mind, were never in the higherphilosophy compeers of Hume, Adam Smith, Burke, and Bentham. But George Eliot, before she wrote atale at all, in mental equipment stood side by side with Mill, Spencer, Lewes, and Carlyle. If sheproduced nothing in philosophy, moral or mental, quite equal to theirs, she was of their kith and kin, ofthe same intellectual quality. Her conception of Sociology was quite as profound as that of Mill, and insome ways keener in insight; if Lewes knew more of psychology or biology, she could teach him muchin history and in morals. There are in “Silas Marner,” “Adam Bede,” and the “Spanish Gypsy,” volcanicbursts of prophetic teaching which Teufelsdröckh never surpassed. That is to say, George Eliot, who ather death left no living novelist to be mentioned beside her, was all her life in intellectual fellowship withthe first philosophic minds of her day. Turn it the other way. None of our English thinkers of the first,second, or even third rank, have resorted to romance as a vehicle of thought. The only possibleexceptions that occur to me are Swift, Dr. Johnson, and Miss Martineau; but “Gulliver,” “Rasselas,” and“Deerbrook” are romances only by courtesy for their authors. Abroad there have been examples of menof foremost intellectual force who have written novels. Of these one only—Goethe—has written a truenovel in a vein worthy of himself. And it is to “Wilhelm Meister” that we may most aptly go foranalogues to the George Eliot cycle of novels. Of course, as poet, as a secular force of European rank,Goethe himself stands apart. But in his “Wilhelm Meister” we have those meditations upon life, humannature, and society, that supreme culture, and a certain Shakespearean way of looking down upon theworld as from a vantage-ground afar, which again and again recur in George Eliot and give her theunique impression of tragic mystery amongst modern novelists.Then again Voltaire, Rousseau, and Diderot wrote prose fictions which may by a stretch of language becalled novels. But the wit of “Candide,” the pathos of “The Religieuse,” the passion of “Héloïse” do notmake up a tale fit to be placed beside “Silas Marner,” as a complete gem of art in the true field ofromance. Voltaire, Rousseau, Diderot, Goethe, Victor Hugo, Carlyle may take rank above George Eliotin the sum of the intellectual impulse they gave to their time. But none of them, unless it be the author ofthe “Misérables,” can be said to be her equal in the painting of real life and actual manners.

And here we may find at once the strength and the weakness of George Eliot. With a mental equipmentof the first order, her principal instrument was art. And so she played a double part—as the mostphilosophic artist, or the most artistic philosopher in recent literature. It has been well said that there areflashes of hers which recall Pascal, Dante, Tacitus. There are certainly some which are worthy of Burke,Condorcet, or Vauvenargues. There are single passages which Bacon might have conceived, and otherswhich Montaigne might have written. And again there are thoughts which Coleridge and De Maistrehave never surpassed. One need not compare her in the sum with any of these famous thinkers. It is plainthat in philosophy she has not produced work that can weight with theirs. But it is the sustainedcommerce with men like these, the continually recurring sense that we are in contact with a mind of theirorder, of the same intellectual family, which rouses in us so intense a delight in her novels that we are aptto indulge in hyperbolic language.But the question comes in, and it must be answered, “Could she play the double part perfectly?” Did herphilosophy, culture, moral earnestness, overweight her art? or was her art the complete and easyinstrument for interpreting all that her brain and her soul contained? Few are now convinced that her artwas always equal to so great a demand. For that reason it may be doubted whether it will ultimately takethe very first rank. A few of the greatest sons of men have combined all that their age had attained withsupreme creative ease. Milton, Shakespeare, Dante, and Virgil seem to use their vast intellectual poweras if poetry were their mother tongue, their natural organ of thought. Alone of the moderns, Goethewields his panoply of learning with perfect ease, bounding in his full suit of mail on to his charger likesome paladin, and careering in it over the field as if it were a robe of tissue. But it is given only to the oneor two of the greatest to interpret the profoundest thought, to embody the ripest knowledge, in theinimitable mystery of art.And thus it comes about we so often feel the art of George Eliot to be short o

held; but she retained, and later exhibited in her novels, a sympathetic understanding of religious sentiments which she no longer shared. While still at Coventry she translated from the German Strauss’s “Life of Jesus,” published in 1846. On her father’s death she paid her first visi