Transcription

THE ACCOUNTING REVIEWVol. LXI, No. 4October 1986A Framework for Triple-EntryBookkeepingYujiIjirABSTRACT: Building upon the author's earlier work [1982], which demonstrated thatdouble-entry bookkeeping is not an absolute system defying extensions but is logicallyextendible to triple-entry bookkeeping, this paper develops a framework for a triple-entrybookkeeping system and illustrates it by means of a simple example which includes aworksheet, journal entries, and three basic financial statements-wealthstatement,momentum statement, and force statement. While the earlier work extended the existing twodimensions of bookkeeping (wealth and income) into a third dimension under the samemeasurement unit, namely dollars, this present paper introduces "momentum accounting"under a related but different measurement unit, namely dollars per time period, such as amonth, in such a way that, when mathematically integrated over time, momentumaccounting articulates with wealth accounting in every dimension. Dealing with earnings ratesper time period associated with assets and liabilities, momentum accounting accounts forearnings rates and their changes. Finally, "force accounting" is introduced as the third layerof the accounting system to explain factors that are judged to be responsible for changes inthe earnings rate. Its measurement (dollars per month per month, for example) is induced bythe measurement in momentum accounting, which in turn is induced by the measurement inwealth accounting. In this way, the extension of double-entry bookkeeping is carried outunder a disciplined framework of measurements, which hopefully will direct management'sattention and sensitivity to factors at a level deeper than the level of wealth and income thathas been traditionally dealt with by double-entry bookkeeping.ANearlier monograph showed thatdouble-entry bookkeeping is notan absolute system, defying anyextensions, but is logically extendible totriple-entry bookkeeping by including aset of accounts called "force" in its thirdaxis [Ijiri, 1982]. This paper discusses aframework under which details of tripleentry bookkeeping are now being developed and presents a simple example thatillustrates the interrelationship amongdimensions in triple-entry bookkeeping.Such an effort is of interest from a theoretical standpoint, enabling us to understand the double-entry bookkeeping system from a higher level of perspective. Inaddition, the new system appears tohave practical feasibility, offering a basisThis article was prepared in part based on the author'sseminar presentations made in Australia, New Zealand,and Japan in May-June 1985 as the 1985 AAADistinguished International Visiting Lecturer. Theauthor is indebted, for their helpful comments andcriticisms, to the participants in these seminars held atUniversity of Auckland, University of Melbourne,Monash University, University of New South Wales,Osaka Gakuin University, University of Queensland,University of Sydney, University of Tasmania, TohokuUniversity, and Victoria University of Wellington.Special thanks are due to Louis Goldberg of Universityof Melbourne, whose detailed comments on the author'sYuji Ijiri is Robert M. Trueblood Professor of Accounting and Economics atthe Graduate School of Industrial Administration, Carnegie-Mellon University.Manuscript received July 1985.Revision received December 1985.Accepted April 1986.745This content downloaded from 195.78.109.162 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 12:59:38 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Accounting Review, October 1986746under which some of the fundamentalconcepts in managementaccounting,especially those in variance analysis, canbe extended and integratedwith thoseof financialaccounting.WEALTHAND INCOMEThe key to an extensionof any systemlies in understandingthe logic behindtheexistingsystem.In particular,it is important to understand what single-entrybookkeepingwas and what was addedtoit when the system was extended todouble-entry. The conclusion on thisissue, as elaboratedin Ijiri [1982],is thefollowing: Single-entry bookkeepingdealt with only stock accounts, such asassets and liabilities,while double-entrybookkeepingextendedit to also includeflow accounts, such as revenuesand expenses, under an interlocking, articulated framework.12The role of flow accounts in doubleentry bookkeeping is to explain or to''accountfor"changes in the netbalance in stock accounts based on theunderlyingcauses that are consideredtobe responsiblefor the change. A doubleentry equation,(1)AStockn Flow,expresses the requirementthat changes(denoted by A) in the net balance ofstock accountsthat occurredin period nbe fully accounted for by a set of flowaccountsin the sameperiod. A changeinthe stock is an observed phenomenon;the flow explains why the change hashappened.3Once we understandthat the salientfeatureof double-entrybookkeepingliesin the integrationof flow accountswithstock accounts, its logical extension totriple-entrybookkeepingbecomes clear,namely, it means an integration of anew set of accounts designedto explainchangesin flow accounts.earlier monograph [19821 on triple-entry bookkeepingwere most valuable, and to Jeffrey Rickman of CarnegieMellon University, whose comments on an earlier draftof this paper from the standpoint of mechanics were veryhelpful. The author is also indebted to the editor and twoanonymous reviewers whose editorial comments andsuggestions resulted in a marked improvement of themanuscript.I The integration of income accounts in the bookkeeping framework made double-entry bookkeeping distinctly different from single-entry bookkeeping. SeeLittleton [1933, pp. 22-4], who emphasizes profit andloss and other nominal accounts as the indispensablecomponent in double-entry bookkeeping. See alsoPacioli's [14941use of revenue and expense accounts andthe Profit and Loss (pro e danno) account as a summaryin the overall bookkeeping framework. The practice ofdouble-entry bookkeeping, however, seems to haveexisted in Italy for more than a century before Pacioli'sSumma was published: See, for example, Peragallo[1938] and deRoover [1956]. There are different views onthe distinguishing feature of double-entry bookkeeping.See, for example, Yamey [1956, pp. 7-9] and Goldberg11965, pp. 215-219]. For a more detailed discussion onthe nature of double-entry bookkeeping in contrast tosingle-entry bookkeeping, see Ijiri [19821and referencestherein.2 It is true that in double-entry bookkeeping, assets arerecorded as debits, while liabilities (negative assets) arerecorded as credits. Also, an asset increase is recorded asa debit, while its negation, an asset decrease, is recordedas a credit. The converse is true with a liability change.Such an expression of negativity by transposition, however, is not essential in double-entry bookkeeping, sincenothing whatsoever is lost if all stock accounts (assetsand liabilities as well as their changes) are recorded asdebits and all flow accounts (revenues and expenses aswell as their adjustments) are recorded as credits. It isinteresting to note that at the time of Pacioli's [14941publication, mathematicians did not recognize negativenumbers as a full-fledged mathematical entity, which didnot come about until nearly 1600 (see Kline [1972, p.252]). As a result, Pacioli seems to have taken pains toavoid the use of negative numbers, using transposition tomean negativity (see Peters and Emery [1980]). Actually,in this age of personal computers, there is no reason toavoid the use of negative numbers, especially if by doingso a more homogeneous classification of accounts isachieved. However, without transposition it is possibleto have journal entries, such as a purchase of inventories,in which all accounts are on the debit side and noaccounts show up in the remaining columns. This is not aviolation of the double-entry or triple-entry equationsince all sides of the entry still add to the same number,zero.3 Using the terms in Hempel and Oppenheim [19481,A Stock. is the "explanundum" which is explained byFlow. or the "explanans." For example, an enterpriseowning only cash had a decrease in cash from 30,000 to 20,000. Why did it happen? Flow accounts, collectivelyThis content downloaded from 195.78.109.162 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 12:59:38 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

747IjiriTo comprehend what this extensionmeans in the accounting environment, itis useful to translate stock and flow accounts into accounting terms, "wealth"and "income." Wealth is assets less liabilities. Income is revenues less expenses.There are other flow accounts such ascontributions by owners or distributionsto owners, as well as such flow accountsas purchases, collections, or payments,which do not normally give rise to achange in wealth. But since income-producing activities are the primary sourceof wealth change of interest, flow accounts other than income will be setaside for simplicity of illustration.MOMENTUM,FORCE,AND IMPULSETo extend the wealth-income dichotomy to a trichotomy, it is necessary tointroduce the concept of "the rate atwhich wealth is changing," or equivalently "the rate at which income is beingearned." The concept will be denoted bymomentum. While both wealth and income are measured in monetary unitssuch as dollars, momentum is measuredin monetary units per period, such asdollars per year or per month. Unlike income, for which measurement requiresspecifying two points in time, momentum shows a state (of income beingearned) at any single point in time.Income is then a realization of momentum as time passes.4 Under a stablemomentum, income is defined as momentum times "duration" of momentum.5The concept of momentum is actuallyused in business, although normally thedifference between momentum andincome is not explicitly made. For example, when an executive says "this investment (or that division or that asset) isearning 60 million a year," what theexecutive refers to is momentum, notincome.6Because momentum may be definedand measured at any single point in time,it is conceivable to prepare a "balancesheet" in which all revenues and expenses are treated as stock accounts andmeasured in momentum. Such measurements may be based on a detailedanalysis of asset and liability items interms of their ability to contribute tothe earning process. In this analysis,momentum for monetary assets and liabilities is easy to determine using thepertinent interest rate. For nonmonetaryitems, an analogy with the historical costprinciple may be taken, and we mayadopt what may be called the "historicalmomentum principle." Under this principle, the momentum of an itemacquired is set equal to the momentumof an item given up in exchange, until thechange in momentum is confirmed byrealization, such as actual sale or lease orelse a contract to sell or lease at a fixedprice or rate.adding to - 10,000, explain the reason. The next stepwill be to treat the loss of 10,000 as an explanundum andtry to find its explanans.4 If wealth at time Tis denoted by WT, income betweentime T' and T is WT- Wt., while momentum is d W/dtevaluated at t T.5 An investment of 10,000 yielding interest at the rateof one percent per month has a momentum of 100/mo.If the momentum is stable at this rate, its realization overa year (a one-year duration) will result in an income of 1,200. In mechanics, momentum is defined as mass (m)times velocity (v). Analogously, in the accountinginterpretation, momentum may be defined as investmenttimes yield, e.g. 100/mo 10,000 x I W6o/mo.6 A car driven at 60 miles an hour at a given point intime may or may not go 60 miles in the next hour since thespeed need not remain constant.I The historical momentum principle implies appreciation or depreciation in book value at a constant rate,hence it conflicts with the historical cost principle whichresults in a constant book value. A translation of suchmethods as FIFO, LIFO, the lower-of-cost-or-marketmethod, and various depreciation methods also generates a different result when applied to momentumcompared with their application to wealth. Comparisonsand reconciliations of the differences between accounting principles and standards as they are applied to wealthand as they are applied to momentum offer an interest-This content downloaded from 195.78.109.162 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 12:59:38 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Accounting Review, October 1986748Consider the fact that momentumitself changes over time. Just as the rateof change in wealth is measured inmomentum, the rate of change in momentum must now be measured inanother concept.8 Because there is nosuch concept currently established in accounting, we may seek a concept inmechanics that fits in the definition.That is the concept of force. Force ismeasured as a rate of change in momentum. Hence, in the accounting interpretation, it is expressed in monetary unitsper period squared, such as dollars permonth per month.9Although both momentum and forceare undoubtedly terms that are notfamiliar to accountants and managers,such an introduction of new terms isunavoidable in an extension of a systemlike double-entry bookkeeping. Fortunately, both terms have common-senseinterpretations that fit very well with thetechnical meaning we are seeking."?Since momentum shows a state at agiven point in time, equation (1) may beapplied to momentum, treating it asstock. Namely, we want to account forchanges in the net balance of momentumby means of a set of accounts designed toexpress the reasons for the change inmomentum. Here again, since there is noconvenient term that currently exists inaccounting to describe a set of such accounts, a comparable term in mechanicsmay be considered.There are two requirements that thenew concept must satisfy. Just as wealthand income are both in the same measurement unit, for example, dollars,momentum and this new concept mustbe in the same measurement unit, forexample, dollars per month. Second,just as income is a realization of momentum and is measured by momentumtimes duration when the momentum isstable, the new concept is a realization offorce and is measured by force timesduration when the force is stable. A concept in mechanics that satisfies bothrequirements is called impulse.IFORA FRAMEWORKTRIPLE-ENTRY BOOKKEEPINGTable 1 shows the relationship amongwealth, momentum, income, force, iming subject of study, enhancing our understanding ofwhat these accounting principles and standards meanin a broader context.a"Why did our momentum go down from 5 million amonth to 4 million a month?" an executive may ask;"What are the contributing factors?" Often casualexplanations are given in monthly management reportsto the board of directors. We need to formalize the reasoning behind the attribution to various factors in theform of accounts.9 In mechanics, force is defined as mass (m) timesacceleration (a). In the accounting interpretation, forcemay be defined as investment times acceleration (rate ofchange in yield), e.g., 10/mo2 10,000x0.1 %/mo2,namely the yield, stated as a fraction per month, increases by 0.1 Wo/mo for each one-month duration of,say, an inflationary force. If wealth is W, momentum isM, and force is F, then M dW/dt, and F dM/dt d2W/dt2. Here, the measurement of wealth is theprimary measurement and the measurement of momentum and that of force are derived measurements. It hasbeen observed, however, that the "best" measurementfor one of the three need not be the "best" measurementfor the remaining two. See Ijiri and Noel [1984] for adetailed discussion on the choice of measurement foreach of the three dimensions, comparing the historicalcost and the current cost measurements.'? Concepts and relationships among them in anoriginal field must of course fit in nicely in the appliedfield; but it is also nice if the concepts and relationshipsare not inconsistent with their common-sense interpretations.11In mechanics, impulse is measured as force timesduration. It can also be shown that it is equivalent tomass times velocity, just as momentum is. Although inmechanics impulse is used in particular for situationswhere duration is short, in our accounting application wemay apply it more generally, irrespective of the length ofduration. For a detailed treatment of the concepts andmeasurements of momentum, force, and impulse inNewtonian mechanics, see, for example, French [19711.The analogy with Newtonian mechanics should, however, be pursued only to obtain some valuable insightsinto how the triple-entry bookkeeping framework shouldbe developed. A wholesale translation without regard toits applicability to accounting is dangerous, since afterall, physics and accounting are two different fields ofendeavor.This content downloaded from 195.78.109.162 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 12:59:38 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

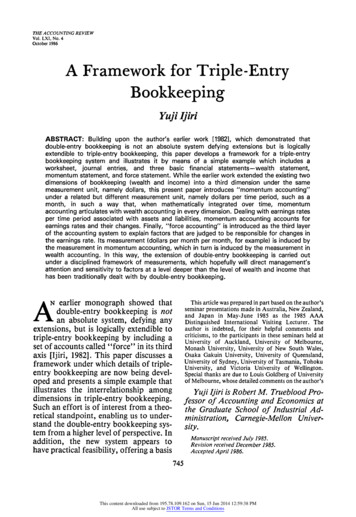

Ijiri749TABLEIA eAccountingSingle-EntryBookkeepingin EntryMomentumBookeepingin tementActionin DollarsForceStatement-P-ADerivativeRelationship--- VAn IntegralRelationship-- A DifferenceRelationshippulse, and one more concept yet to beexplained,namelyaction. On the bottomrow of Table 1 we have the familiartwodimensionsin wealthaccounting,that is,wealth and income, setting aside thethird dimensionof action for now. Thetwo dimensionsare tied togetherby thedifference relationship, AWealth Income, both of which are stated in monetary units such as dollars.We now move to the second row ofTable 1, which expresses the doubleentry equation (1) applied to momentum, namely AMomentum Impulse.That is, changes in momentum at anytwo points in time are fully accountedfor by impulse, whose accounts expressthe underlyingforces that are judged tobe responsible for the momentumchange. Both momentum and impulseare stated in monetaryunits per period.This particular layer of accounting,called momentum accounting, is analogous to the conventional double-entryframework for wealth and income, except that the primary object of accounting is momentum instead of wealth.The top row of Table 1 shows the dimension for force accounting. Its onlydimension is force, which is stated inmonetary units per period squared.While conceptually it is possible to define a concept that deals with a rate ofchange in force, a higher dimension isnot considered at this time. (Such aconcept will become necessary if thebookkeeping system needs to be furtherextended to quadruple-entry bookkeeping.) Hence, force accounting has to bebased on a single-entry bookkeeping system.Two types of relationships exist acrossThis content downloaded from 195.78.109.162 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 12:59:38 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

750The Accounting Review, October 1986different layers of accounting. One is thederivative relationship that exists between wealth and momentum as well asbetween momentum and force. One dealswith the rate of change in the other, andmathematically one is the time derivativeof the other. This relationship is shownin Table 1 by diagonal arrows. The otheris an integral realtionship connectingconcepts vertically in Table 1, such asmomentum-income and force-impulse(as well as impulse-action, which will beexplained later). For a constant momentum or force, income is momentumtimes duration and impulse is force timesduration, as mentioned earlier. Moregenerally, income is measured as anintegration of momentum, and impulseis measured as an integration of force,both over a given period of time.The diagonal, derivative relationshipand the vertical, integral relationshipthat tie wealth, momentum, and incomeare the converse of each other if the integration constant is set equal to the beginning balance of wealth. Hence, theequality holds between the wealth dimension and the income dimension whenthe beginn

746 The Accounting Review, October 1986 under which some of the fundamental concepts in management accounting, es- pecially those in variance analysis, can be extended and integrated with those of financial accounting. WEALTH AND INCOME The key to an extension of any system lies in understandi