Transcription

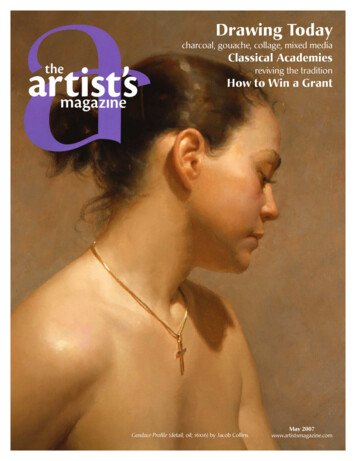

Drawing Todaycharcoal, gouache, collage, mixed mediaClassical Academiesreviving the traditionHow to Win a GrantCandace Profile (detail; oil; 16x16) by Jacob CollinsMay 2007www.artistsmagazine.com

Process ofIlluminationIn his classical approach to creatingand instructing, Jacob Collinsbelieves in taking things slow.www.artistsmagazine.com · May 2007 Interview by Lisa Wurster30While perhaps best known for his paintings of thefigure, mainly of the female in repose, Jacob Collinsis equally adept at still life and landscape. In fact, onequality all of his paintings share is a signature breathof light. This delicate illumination, accompanied byequally powerful darkness, caresses either skin, objector sky. Collins’s style is frequently compared to that ofthe 19th-century painters, and although his paintingsare certainly classical in approach, they have a decidedlycontemporary look. Friend and former student JulietteAristides says of his work, “Jacob’s paintings have asublime tonal quality and his paint handling has thefluidity of an old master’s.”An instructor at the Grand Central Academy ofArt, a school he founded with several former students,Collins also runs the Water Street Atelier out of theground floor of a Manhattan carriage house. It’s a homehe shares with his wife, Ann Brashares—the bestsellingauthor of The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, andtheir three children. While hesitant to divulge paintingtechniques in the pages of a magazine (“A little learningis a dangerous thing ”), in this interview Collins opensup about some of his artistic influences and shares withreaders a drawing demonstration. Lisa Wurster is associate editor for The Artist’s Magazine.

Study for Lise(at right; graphite,16x231/2) andLise (below; oil,36x46)

When did you decide to begin a life in art?I had a clear feeling from early on that I wanted todo this. Also, my grandmother was an artist and myparents were very encouraging; they saw how excitedand driven I was and would buy me art books. As ayoung man, I tried to draw accurately and expressively,though not in a particularly artistic way. To a certainextent, I was looking to the dynamic muscular figuresin, say, Marvel comics. That natural segue from copyingcomics to looking at Michelangelo or Rubens happensfor an awful lot of young artists, especially young boys.It’s coming from a similar place—the desire to makethese expressive, dynamic figures. So I found myselfstepping from a childhood idiom to a slightly moregrown-up one.You mentioned Marvel comics as a childhoodinfluence. Did you have a preferred comicbook character?I really liked Spiderman—the way he could shoot hisweb out of his wrists, and he was agile and powerful. Iguess that would be an early iteration of my passion forboth the lyrical and the monumental.www.artistsmagazine.com · May 2007With your wife an author and you an artist, it mustbe a very creative household. Have your threechildren expressed any interest in art?Yeah, Ann is upstairs and I’m downstairs (laughs). Thechildren are still a little young: Sam is 12, Nate is 8 andSusannah is 5. They’re very creative and imaginativekids, but we’re certainly not putting any pressureon them.32For a long time, you copied the old masters in severalmuseums. Do you recommend this to other artists?Yes, very much. When I was a teenager, I would go tothe Met and copy from Rembrandt, Gustave Courbetand others, which I did for a number of years. Most ofthe time when I copied, I did so in oil, watercolor orpencil, and although I wasn’t employed as an officialcopyist, I learned a great deal.I also copied from art books. It’s harder to copy apainting than a drawing out of a book, because with apainting, the texture and degrees of transparency areThe Water Street Atelier, GrandCentral Academy and the HudsonRiver School for LandscapeCollins started the Water Street Atelier on Water Streetin Brooklyn in 1994 as a small and private atelier. Theatelier is now located on the ground floor of Collins’sManhattan home and serves a group of 15 studentswho work with the artist in a loosely structured programover the course of several years. Generally, the studentsbegin with drawing, progress to painting plaster castsof sculptures, and grisaille (a painting or drawing donein shades of gray), then finally, students begin paintingthe figure.“The atelier is wonderful, but New York has somany artists who really care and love this approach toart, and it seemed that group was underserved,” Collinssays. So he founded the Grand Central Academy ofArt to offer highly focused training in drawing, paintingand sculpture. The academy runs on a three-yearprogram, the first year of which is almost exclusivelydrawing studies. Currently, the school accepts 15students a year into the program, and this year theprogram will be accepting its second group of first-yearstudents. The school also offers intensive night classesand summer workshops.Collins is currently working on his newest venture,the Hudson River School for Landscape, situated inthe Catskills. Rather than a standard art class, this schoolmay become a permanent fixture, much like an artist ‘scolony. “Some colonies are located in beautiful places,with artists who aren’t interested in making beautifulpaintings out of the landscape,” he says. “This schoolwould, I hope, bring together the reawakening love ofthe old American painters, the vigorous but unfocusedscene of contemporary landscape painting, and theurgent need for renewed reverence for the land.” Classesbegin this summer.

Candace Profile (oil, 16x16)“I begin some drawings loosely, whileothers I start very carefully, drawing slow,crisp lines. When painting, I might startout with a transferred drawing or witha lot of messy paint and hope for thebest,” says Collins. “This demonstrationfor Marc (on page 35; graphite, 24x18),covers a few of the ideas that I think ofwhen drawing the figure. I don’t wantto give the impression that these stagesrepresent a set of drawing rules. Thereare many ways to draw beautifully.It’s important to let the drawing be aninvestigation and sometimes, in orderto investigate, you need to go off thepath.”I begin drawing the simplest visualI refine the central shape whileshapes. I’m looking for overall axesdividing it into subshapes, trying toand directions. My main interest issee every tilt and shape as truly as Igetting the particular spirit of thecan. (10 minutes)middle of the pose, in this case thepelvis, torso and thigh. (1 minute)Continued on page 34.www.artistsmagazine.com · May 2007Drawing offthe path33

www.artistsmagazine.com · May 200734As the middle becomes truer, I build the outer partsI continue to make my shapes and tilts true. Measuringonto it. So far, I’ve mostly measured ratios by eye,more now as I shift intervals and ratios, I divide thebut now I start to loosely check a few measurements:shadow and light shapes. I refine the middle first andhalves, quarters, plumbs, horizontals. (25 minutes)then work my way out. (1 hour)I patiently adjust the shapes and tilts. Up to this point,In this first pass of modeling, I develop my values byI’ve had anatomy and construction ideas on the backconceptualizing the surfaces and the direction of theburner. Now I begin to engage the dimensional realitylight. (about 12 hours)of the figure. (about 6 hours)

from realizing their potential. The photograph providesa perfectly flat, nonexperience to copy. If the artist’sdevelopment is built up on a series of nonexperiences,his work will not be as rich as it could be. Workingfrom photographs can prevent an artist from reallyconnecting to this powerful humanist tradition.You work in still life, landscape and figure. Whichsubject or genre brings you the greatest satisfaction?Each genre satisfies different needs. I just spent the lastthree years painting figures with the idea that they’rethe hardest, certainly the most taxing genre,and you have to be the most on your game.If you have significant drawing problems,the figure will fall apart and it will readwrong emotionally.Now I’m turning my attention back topainting landscapes and still lifes. My nextshow is going to be comprised of still lifes.They aren’t aspiring to be monumentalworks in any way, but ideally they’renuanced and sensitive little paintings. I lovepainting them because there’s a feeling ofmusical, flowing experience. The drawingdoesn’t matter as much—what you’re reallyafter is a feeling of clarity and beauty.Switching to landscape painting, whichis my next big project, is so exciting becauseI get to be out of the studio. I spend somuch time in my studio, which can be verydark, so it can begin to feel as if I’m a moleunderground. To be outside and spendingtime in the sun and wind—and paintingthings that are changing and moving—that’sdifficult, but also invigorating.What about when painting landscapes—do youwork outside for those?I utilize plein air painting as one of the important imagegathering ways to develop a picture, so I do all of myYour figures seem so lifelike, as if theflesh has weight. Is it important that youpaint the figure from life?I paint the figure only from life—and frommy imagination or previous experiences.The best way to say it is that I don’t workfrom photographs. The over reliance onphotography holds so many artists backAs I push the modeling, I make the form fuller and clearer in the lightsand subtler and flatter in the shadows: active lights, passive shadows.At this stage, I make every effort to think spatially. Sometimes I try toimagine that my drawing is a little three-dimensional sculpture, andthat my pencil is a sculptor’s tool: I’m reaching my pencil through thepaper and into an imaginary space to carve the figure. (2 weeks)www.artistsmagazine.com · May 2007such important factors. When you’re copying from abook, you have a limited idea of what the painting reallylooks like, but you can learn the tonal range and colorrelationships. The colors are usually going to be a littleoff, but at least you can learn the organization of valuesin the composition.35

www.artistsmagazine.com · May 2007studies (pencil and chalk drawings) outside, but I’mnot a plein air painter per se. Generally, when I paintlandscapes I’ll do drawings of leaves, cliffs or branches,and all of that gets integrated along with the plein aircolor studies and compositional paintings. These worksget folded into preparatory medium-size paintings,which then go into making a larger finished work.36Green Onions (at top; oil, 14x20) andWoman (Irma) (above; oil, 13x16)Your work has been compared to Caravaggio’s,with its strong contrasts of light and dark. Can youaddress your use of lighting and palette?I love earth colors. If I can, I try to use only umbers,siennas, ochres, Naples yellow and flake white. WhenI’m composing, I try to remember that the first impactthe picture will have—what draws you to it—is thebig, simple value pattern. I think Caravaggio is anextraordinarily important artist in a significant way.His influence changed how painters thought about

Born in New York in 1964, Jacob Collins studiedart in Europe, at the Art Students League and theNew York Academy of Art. He received a bachelorof arts degree from Columbia College in 1986.He is founder of the Water Street Atelier andcofounder of the Grand Central Academy of Art.Besides appearing in more than 15 group andsolo exhibitions, Collins’s work resides in severalnotable collections, including the Forbes Collectionand at Harvard University’s Fogg Museum. He’srepresented by Hirschl and Adler Modern in NewYork City. Visit www.jacobcollinspaintings.com tolearn more.paintings, with the dominant power of the single lightsource and with powerful areas of light and dark. Hedidn’t invent those ideas, but he expressed them sopowerfully. Over the course of my life, I’ve been veryexcited and still am about the Hudson River landscapepainters. I love their reverence for the land, their tonalorganization, draftsmanship, commitment to beautyand their use of the possibilities of oil paint: thick andthin, opaque and transparent, smooth and rough. Ialso love the way they studied nature so intently. That’swhy I decided to start the Hudson River School forLandscape (for more information, see the sidebar onpage 32).Are you trying to convey a specific idea to theviewer with your portraits? What about withthe landscapes?I’ve always loved beautifully drawn and rendered faces.When I paint a portrait, I try to make an excellentlyconstructed head, clearly drawn and delicately realized.Are there any ideas that you repeatedly stress tostudents?I think it’s an important element to have consistencyin your materials and consistency in your environmentand studio. I tell students who are learning to paint thefigure that the goal is to do a figure as well as you can.Then for the next figure, use the same tools, medium,paints and process. Each time you do a figure, you canadjust each of the component elements and improveeach element a little bit, until the whole process overallimproves. That’s very important, even in my own work.It’s a relatively gradual process, a smooth evolution.What’s your favorite part of the artistic process?Each stage is infinitely vexing, but also thrilling. Thestart is intimidating. If you screw it up, your wholeproject will be miserable. But it’s also the freest andmost significant moment. Finishing is torture. Thetendency to judge yourself must be resisted, but that’simpossible. There’s always some newly seen flaw. Butthe little glimpses of beauty between the anxiety makeit worth it.You work in the classical tradition, yet your paintingshave a modern feel. Is there a technique for keepinga painting from looking dated?I’ve found that one way to make paintings look datedis to try to make them look contemporary. Eventually,contemporary will be dated. If I work really hard tomake my paintings look 2006, in 10 years they’ll look10 years old. But if I try to make them look honestand

figure, mainly of the female in repose, Jacob Collins is equally adept at still life and landscape. In fact, one quality all of his paintings share is a signature breath of light. This delicate illumination, accompanied by equally powerful darkness, caresses either skin, object or sky. Collins’s style is frequently compared to that of the 19th-century painters, and although his paintings are .