Transcription

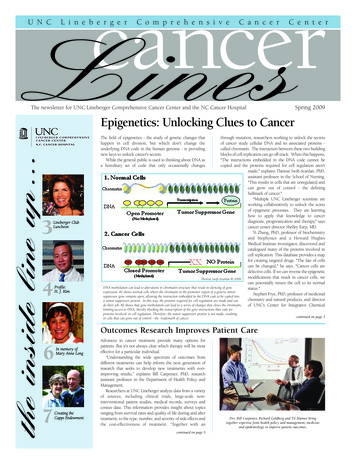

34014 UNC.qxp:CLines9 044/22/097:15 AMPage 2cancerLinesU N CL i n e b e r g e rC o m p r e h e n s i v eC a n c e rC e n t e rThe newsletter for UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center and the NC Cancer HospitalSpring 2009the inside line up .Epigenetics: Unlocking Clues to CancerThe field of epigenetics - the study of genetic changes thathappen in cell division, but which don't change theunderlying DNA code in the human genome - is providingnew keys to unlock cancer's secrets.While the general public is used to thinking about DNA asa hereditary set of code that only occasionally changes3Lineberger ClubLuncheon4Profile:H. J. Kimthrough mutation, researchers working to unlock the secretsof cancer study cellular DNA and its associated proteins called chromatin. The interaction between these two buildingblocks of cell replication can go off-track. When this happens,"The instructions embedded in the DNA code cannot becopied and the proteins required for cell regulation aren'tmade," explains Theresa Swift-Scanlan, PhD,assistant professor in the School of Nursing."This results in cells that are unregulated andcan grow out of control - the defininghallmark of cancer.""Multiple UNC Lineberger scientists areworking collaboratively to unlock the scretsof epigenetic processes. They are learninghow to apply that knowledge to cancerdiagnosis, prognostication and therapy," sayscancer center director Shelley Earp, MD.Yi Zhang, PhD, professor of biochemistryand biophysics and a Howard HughesMedical Institute investigator, discovered andcatalogued many of the proteins involved incell replication. This database provides a mapfor creating targeted drugs. "The fate of cellscan be changed," he says. "Cancer cells aredefective cells. If we can reverse the epigeneticmodifications that result in cancer cells, weTheresa Swift-Scanlan 2008can potentially return the cell to its normalDNA methylation can lead to alterations in chromatin structure that result in silencing of genestatus."expression. #1 shows normal cells where the chromatin in the promoter region of a generic tumorStephen Frye, PhD, professor of medicinalsuppressor gene remains open, allowing the instruction embedded in the DNA code to be copied intochemistry and natural products, and directora tumor suppressor protein. In this way, the proteins required for cell regulation are made and cando their job. #2 shows that gene methylation can lead to a series of changes that closes the chromatin,of UNC's Center for Integrative Chemicallimiting access to DNA, thereby blocking the transcription of the gene instructions that code forproteins involved in cell regulation. Therefore, the tumor suppressor protein is not made, resultingin cells that can grow out of control - the trademark of cancer.continued on page 3Outcomes Research Improves Patient Care6In memory ofMary Anne Long7Creating theCapps EndowmentAdvances in cancer treatment provide many options forpatients. But it's not always clear which therapy will be mosteffective for a particular individual.“Understanding the wide spectrum of outcomes fromdifferent treatments can help inform the next generation ofresearch that seeks to develop new treatments with everimproving results,” explains Bill Carpenter, PhD, researchassistant professor in the Department of Health Policy andManagement.Researchers at UNC Lineberger analyze data from a varietyof sources, including clinical trials, large-scale noninterventional patient studies, medical records, surveys andcensus data. This information provides insight about topicsranging from survival rates and quality of life during and aftertreatment, to the type, number, and severity of side effects andthe cost-effectiveness of treatment. “Together with ancontinued on page 5Drs. Bill Carpenter, Richard Goldberg and Til Stürmer bringtogether expertise from health policy and management, medicineand epidemiology to improve patient outcomes.

34014 UNC.qxp:CLines9 044/22/097:15 AMPage 3director’sMessageDuring these tougheconomic times,every dollar wespend must moveus a step closerto fulfilling ourmission: to reducecancer occurrenceand death inNorth Carolinaand the nation.Thismissionreceived a ringingendorsementDr. Shelton Earpin 2008 fromLineberger's over 5,000 private donors and fromthe General Assembly's funding of NorthCarolina Cancer Hospital and the UniversityCancer Research Fund. These endorsementswill help us save lives and reduce suffering fromcancer in North Carolina and beyond.In practice, this mission covers a panorama ofactivities ranging from discovery to innovationto delivery. Our work fits together in complexways, and we often find that an investment inone area yields unexpected benefits in others.We've been calling these outcomes the multipliereffect.We see the multiplier effect in the way thatthe UCRF's investment has helped position theuniversity and UNC Lineberger ComprehensiveCancer Center to take advantage ofopportunities like the National Institutes ofHealth's Clinical Translational Sciences Awardprogram. The infrastructure in place as a resultof the UCRF helped UNC secure an additional 35 million in grant funding over five years.It helps us take advantage of promisingopportunities and innovative ideas by providingstartup funds through Lineberger donorsupported pilot projects and the UCRFInnovation Awards, generating publications andnew external grant funding based on the dataproduced during thestartup phase.Wearealsouniquely positioned tobenefit from federalrecoveryinitiativessuch as the AmericanRecovery and Reinvestment Act, signed into law in February.The economic stimulus package provides anunprecedented increase of 8 billion in basic researchfunding for the NIH. The president's 2010 budget currently under discussion in Washington - proposesdoubling the National Cancer Institute's funding overthe next ten years.We see a multiplier effect every time we makea strategic hire of a top-notch physician orresearcher, people whose life's work is to savelives and prevent, halt and reverse the effects ofcancer. In addition to giving us the capacity tosee more patients, the more than 16 new highlytrained physicians we've hired since the UCRFwas established bring expertise to UNC thatbenefits several of our multidisciplinary, patientfocused treatment programs. Donor-supportedearly phase clinical research projects harnesstheir expertise, allowing us to offer new anddifferent treatments, get involved in moreleading-edge clinical trials and create a broaderrange of coordinated support programs forpatients going through treatment.New researchers are multipliers, as they jointhe top-notch faculty already here as a newcollaborator on high-impact projects thatsuccessfully compete for external funding. Ourability to attract faculty who already successfullycompete for funding from agencies like the NIHbrings more research dollars into the NorthCarolina economy. The community of interestwe have around the problem of cancer benefitsmultiple schools and colleges at UNC,supporting them in fulfilling their research,educational and service objectives and making abetter future for our state.The most important multiplier, however, isone that's hard to quantify. It is the lives savedand the quality of life gained by cancer patientswho stand to benefit from new discoveries andinnovative treatments developed here. It's theyears of productive health gained by people whoLineberger Club Celebrates Survivors,Donors and Tar Heel VictoryMore than 300 people attended the 2009 Lineberger Club event in February,enjoying a lunch at the Carolina Club and a UNC men's basketball team victoryover the University of Virginia. The event honors the more than 450 LinebergerClub members who annually donate 1000 or more to UNC Lineberger's cancertreatment, research and prevention programs. Guests at the lunch includedLieutenant Governor Walter Dalton and his wife, Lucille, Speaker of the House JoeHackney and his wife, Betsy, and Senate Majority Leader Tony Rand and his wife,Karen. This year's program featured patient Christina Gianoplus, from Wilmington,NC, who shared her inspiring story of her treatment for colon cancer by Dr. RichardGoldberg, UNC Lineberger associate director. Pictured (left to right) are Shelley Earp, MD, UNC Lineberger director,Richard Goldberg, MD, UNC Lineberger associate director,and the Gianoplus family: Nicholas, Christina, Alex and Greg.2cancerLines Spring 2009Cancer Lines is a tri-annual publication of theUNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Centerand the N. C. Cancer Hospital.Dr. H. Shelton Earp, III, DirectorDr. Richard M. Goldberg, Associate DirectorDr. Joseph S. Pagano, Director EmeritusDebbie Dibbert, Director of External AffairsEllen de Graffenreid, Director ofCommunications & MarketingDianne G. Shaw, Deputy Director of CommunicationsAlyson Newman, Design & Layout Please remove me from your mailing listName Please add me to your e-news listEmail address Please add me to the Cancer Center’s mailing list:NameAddressCity, State, ZipUNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer CenterCB# 7295Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7295(919) 966-5905www.unclineberger.orgPrinted on Recycled Paperbenefit from what we learn about the causes ofcancer, the behavior of risk factors and thecomplex interaction between genes and theenvironment. It is fathers who get to walk theirdaughters down the aisle at their weddings,great-grandmothers who live to see the nextgeneration, young mothers who see theirchildren graduate from high school and collegeand brothers and sisters who don't have to saygoodbye too soon.At the end of the day, these are the multipliersat the heart of our mission.

34014 UNC.qxp:CLines9 044/22/097:15 AMPage 8microarray. "Methylation of cancer-related genes hasdoctors can have a difficult time discerningbeen found to be related to clinical features of breastmelanoma from benign moles based on appearancecontinued from page 1tumors, response to endocrine therapy, andand pathology.outcomes."Kathleen Conway Dorsey, PhD, research assistantBiology and Drug Discovery, also studies chromatin,Swift-Scanlanprofessor of epidemwhich he says "is implicated in all processes of cellreceived an NIH awardiology, and Nancydifferentiation and is highly relevant to theand a Susan G. KomenThomas, associatemisregulation of such processes in cancer."grant to study DNAprofessor of dermatology,"I'm focused on discovery of chemical toolsmethylation in breastreceived an NCI granttailored to targets that regulate chromatin state,tumor subtypes. "SometoidentifyDNAsome of which will have the potential to treatgenemethylationmethylation patterns cancer." Before joining UNC, Frye co-inventedchangesmaybea cancer mechanismGSK's Avodart, a drug that shrinks enlarged prostateimportant in earlythat inactivates theglands and is being studied as a preventative fordetection and prognosis'brakes' on cell grownprostate cancer.because they occur earlyand causes tumors.Other UNC Lineberger scientists are focusing onin tumor developmentThese patterns canwhat 'goes wrong' in cells to cause cancer. Ianand may vary withdistinguish melanomasDavis, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics, ishistory of estrogenfrom benign moles withinvestigating how the molecular switches thatexposure," she said.highsensitivity,control the 'on' and 'off' states of genes go awry in"Improved prognosis isspecificityandcancer, particularly childhood cancers. "We arepossibleifgenereproducibility.working toward a broad and deep understanding ofmethylation changes"Comprehensivethe rules that govern gene regulation in cancer," hecan reliably identifyanalysis of promotersays. "By understanding how cancer cells aretumorsubtypesmethylation, whichdependent on gene expression and epigeneticand predict clinicaloccurs widely inchanges, we hope to inform the development ofYi Zhang, professor of biochemistry, and Brian Strahl, associateoutcomes such ashuman melanomas,targeted therapies to block them."professor of biochemistry, use telephone cords to illustrate howcancer recurrence andoffers a promising toolBrian Strahl, associate professor of biochemistrystrands of DNA are packaged in our cells. Photo by Steve Exum.response to treatment."that will be a first stepand biophysics, has an NIH grant to studyAnother breast cancer project focuses ontoward the development of standard diagnosticepigenetic modifications in yeast, which has manytechnologies and concepts developed in modeltests, thereby decreasing under- and overof the epigenetic markers found in humans. "It's notsystems and applying them to the treatment oftreatment," Dorsey says.a true cancer cell, but we're learning the nuts andpatients. One example is FAIRE, which stands forThe long-term goal of three breast cancerbolts of how the epigenetic system works," heFormaldehyde-Assisted Isolation of Regulatoryresearch projects is to decrease mortality by betterexplains. "If we can manipulate enzymes thatElements. FAIRE is a simple, low-cost way to isolatematching treatment decisions with each woman'smodify or control the epigenetic landscape, we haveand identify unpackaged regions of DNA across theclinical history and tumor type.a chance to regulate thewhole genome. This information is valuable,Dorsey's project focuses onpotential for cancer orbecause when DNA is unpackaged, or "open", itmethylation in breast cancer.prevent its spread."Multiple UNC Linebergerindicates that the underlying information is beingThe Carolina Breast CancerSeveral UNC Linebergerscientists are workingused by the cell. "Using FAIRE, we propose toStudy (CBCS) found thatstudies involve specificcollaboratively to unlock theidentify the entire set of DNA-encoded regulatoryAfrican Americans are morecancer types and havesecrets of epigenetic processes.elements active in 100 human breast tumorslikely to develop tumors thatimportant implications forexcised from women treated at UNC Hospitals,"generally indicate a poorerhow patients will be treatedThey are learning how tosays Jason Lieb, PhD, associate professor of biology.prognosis compared within the future. For example,apply that knowledge toUsing tumor samples representative of all knownthose of white women. Dorseyearly diagnosis of melanomacancer diagnosis,molecular subtypes from UNC's Tissuereceived a Susan G. Komenis crucial because survivalProcurement Program, Lieb has already identifiedgrant to study the basis forrates are extremely differentprognostication and therapy.open-chromatin signatures that have implicationsthesedifferencesusingthebetween localized and- Shelley Earp, M.D.for treatment.new Illumina methylationmetastatic disease. ButEpigenetics Dr. Hyman Muss to Lead New Geriatric Oncology Programother non-cancer illnesses. TheHyman B. Muss, MD, has joined theprogram will develop clinical trialsUNC Lineberger Comprehensiveintegrating prevention, treatment,Cancer Center as a professor ofquality of life, and translationalmedicine and will develop and lead aresearch focused on older patients withnew program in geriatric oncology.cancer. Additionally, the program willMuss comes to UNC from thedevelop educational programs forUniversity of Vermont Cancer Centerstudents, house staff, fellows, andwhere he served as associate director offaculty concerning aging and cancerclinical research and division directorto insure the development of researchof hematology/oncology. He wasand clinical programs dedicated topreviously at Wake Forest Universityadvancing cancer care for olderComprehensive Cancer Center inDr. Hy Musspatients.”Winston-Salem, NC, where he was aShelley Earp, MD, director of UNC Linebergerprofessor of medicine and associate director forComprehensive Cancer Center, said, “Simplyclinical research.put, Hy Muss is a national treasure. His clinicalMuss said, “Our objective for the Geriatricresearch accomplishments are outstanding, butOncology Program will be to ensure the highestare frankly secondary to his skills as a doctor,quality of oncologic care for older patients whileteacher, and colleague. We are thrilled that thefactoring in the patient's functional status andUniversity Cancer Research Fund has allowed usto bring Hy back to North Carolina to start thenew, much needed Geriatric Oncology effort.”Muss earned his undergraduate cum laudedegree in chemistry from Lafayette College inEaston, PA and his medical degree from the StateUniversity of New York Downstate MedicalCenter in Brooklyn, NY. He completed hisinternship, residency and a research fellowshipat Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston, MA.He was honored for his military service inVietnam with a Bronze Star.He serves on the Board of Directors for theAmerican Society of Clinical OncologyFoundation and for the Cancer and LeukemiaGroup B (CALGB) Cooperative Group, and onthe editorial boards of several publicationsincluding Oncology, The Breast Journal, andCURE. cancerLinesSpring 20093

34014 UNC.qxp:CLines9 044/23/099:27 AMPage 5facultyProfileThe son of a physician and a nurse, H.J. Kim admiredhis South Korean father's profession. So aftergraduating from Dartmouth College in 1988, heenrolled in the University of Virginia's MedicalSchool. A month later, his father was diagnosed withnon-Hodgkin's lymphoma, requiring surgery. “Afterthat, oncology was a logical interest of mine,” he says.Kim wanted a combined career in surgery andresearch, and finding a home to practice both was notthat easy. “I struggled at several other big-nameinstitutions to find suitable research mentors butcould have easily picked several here at UNC,” hesays. Kim trained at several medical centers,completing his residency at the University ofChicago, a research fellowship at the University ofTexas Medical Branch in Galveston, and a fellowshipin surgical oncology at Memorial Sloan-Ketteringbefore coming to UNC.Kim also is collaborating withAl Baldwin, William R. Kenan,Jr. Distinguished Professor ofbiology and associate director atLineberger, to understand whysarcomas and gastrointestinal cancers are resistant tochemotherapy.“The outcome of research is less certain than theimmediate, tangible results of surgery. I amfortunate to have very established mentors who arewell-recognized for their work,” Kim says. “It's thoseWork/Life Balance“What I do love about UNC is that the people hereunderstand family is important. The surgicaloncology division works really hard and we aresurprisingly all married and have well-adjustedfamilies, which is quite rare,” he boasts.Kim maintains his busy schedule while helpinghis wife Dana, a nurse practitioner, raise their youngchildren Kristina, 9, Jessica, 7, and Charlie, 5. They'rea close bunch who love the outdoors, the beach - orbeing homebodies.“If it was up to me,” Kim laughs, “I'd like nothingbetter than to vegetate in front of the TV with a SlimJim and a Mountain Dew.”Research and SurgeryIn addition to his surgical schedule, Kim in involvedin several research projects. He and Carol Otey,associate professor of cell and molecular physiologyat the School of Medicine, are investigating whatcauses breast and pancreatic cancers to metastasize.research Dr. H.J. Kim pursued a career in surgical oncology afterhis father was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphomaBriefsLong-term use of nutrientsupplements may increase cancer riskA new study shows that certain people especially smokers - who took dietarysupplements containing beta carotene, retinol,vitamin A, lycopene and lutein are at higher riskof developing lung cancer than the generalpopulation. Specifically, the study found that useof retinol and lutein supplements for four yearsor longer was associated with increases in lungcancer risk of 53 percent and 102 percent,respectively. "The amount of time the persontook supplements seemed to have a greater effectthan the dose," said Jessie Satia, PhD, MPH,associate professor of epidemiology andnutrition at the UNC Gillings School of GlobalPublic Health and UNC Lineberger member.Even a modest dose, if taken for a long time, canincrease the risks of lung cancer, especiallyamong smokers."New genomic test may guidebreast cancer treatment choicesOne in eight women in the United States willreceive a diagnosis of breast cancer in her lifetime.But by specifically measuring the activity level of asmall subset of the 20,000 plus genes that may be4cancerLinesSpring 2009relationships that provide confirmation of why Iremain at a university center: the opportunity tochange cancer care in the long run.”On top of all that, Kim leads colleagues in theDivision of Surgical Oncology to create aprogram that will train future surgeons in thesurgical management of malignant diseases.Programs like this are essential to keepingdoctors in surgical oncology, especially with ashortage expected in coming years because of anaging population demanding more procedures.turned on or off in each tumor,a new genomic test can givepatients a more accuratepicture of how their diseasemight progress. "Based on thegenomics of a tumor, we canmake good predictions about how a patient mightdo, but we can also define predictive markers thattell us which drugs to give patients," said study coauthor Charles Perou, PhD, associate professor ofgenetics and pathology and a UNC Linebergermember. "We've demonstrated that this test canpredict the likelihood a patient will relapse and candefine the biologic subtype of their tumor - pieces ofinformation that together could be used to maketreatment decisions."New approaches may preventtransplant rejectionTo prevent the rejection of newly transplantedorgans and cells, patients must take medicinesthat weaken their entire immune systems,increasing susceptibility to life-threateninginfections. But researchers at UNC Linebergerhave discovered a subset of cells called TH17that seems to trigger the immune system toattack transplanted cells in the first place. "Ourhope is that uncovering the mechanisms thatcause graft-versus-host disease will allow fortreatments that specifically target its causes anddo not have the harmful side effects of traditionalimmunosuppressive therapy," said study leadauthor Jonathan Serody, MD, a UNC Linebergermember and the Elizabeth Thomas Professor ofMedicine, Microbiology and Immunology.Research on the TH17 branch has alreadysparked the interest of some pharmaceuticalcompanies such as Wyeth, and Serody predictsthat there will be a number of drugs coming outin the next five years to treat immune-based skindiseases.Circadian clock changes cansuppress cancer growthDisruption of the circadian clock - the internaltime-keeping mechanism that keeps the bodyrunning on a 24-hour cycle - can slow theprogression of cancer. UNC researchers foundthat genetically altering one of four essential"clock" genes actually suppressed cancer growthin a mouse model commonly used to investigatecancer. "Our study indicates that interfering withthe function of these clock genes in cancer tissuemay be an effective way to kill cancer cells andcould be a way to improve upon traditionalchemotherapy," said senior study author AzizSancar, MD, PhD, a UNC Lineberger memberand Sarah Graham Kenan Professor ofBiochemistry and Biophysics in the School ofMedicine. "These results suggest that altering thefunction of this clock gene, at least in the 50percent of human cancers associated with p53mutations, may slow the progression of cancer.In combination with other approaches to cancertreatment, this method may one day be used toincrease the success rate of remission."

34014 UNC.qxp:CLines9 044/22/097:15 AMPage 6Program SPEEDs Research to PatientsThe University of North Carolina's mission is toserve the entire state. A new program aims toincrease the University's reach by “bringing moreof what we know works to prevent and treatcancer to more people, in more places, in lessdisseminating what we know works, buildingcapacity within systems to adapt and implementthese approaches, and providing support tohealth care providers and systems is critical tospeeding up this process.”Through the program, researchassociates are currently at work in theAsheville, Greenville and Wilmington areason: Implementing smoking cessationapproaches for pregnant women andparentsSocial marketing to increase thenumbers of young women receiving theHPV vaccineHelping to evaluate basicprevention programs to help reduceCathy Melvin points out NC SPEED sites to Senator Joe Sam Queenobesity, increase physical activity, improveduring a legislative tour of the NC Cancer Hospital.nutrition and quit smoking - all factors intime,” explains Cathy Melvin, PhD, director ofthe development of cancerthe dissemination core facility at UNCTesting the feasibility of reaching AfricanLineberger and research associate professor ofAmerican men in barbershops with messagesmaternal and child health in the UNC Gillingsand tools to increase their physical activitySchool of Global Public Health. “We want toImproving systems for colorectal andmake sure that people in every region, andbreast cancer screening and follow-up amongeventually every county, can be actively engageduninsured and minority populationsin efforts to apply proven strategies formore quickly implementing evidence-basedNC SPEED research associates help linkinterventions and achieving excellence in healthindividuals and organizations in North Carolinaand healthcare research and practice.”communities and healthcare systems with UNCThe result is NC SPEED (Statewide Push forand Lineberger researchers so that both groupsExcellence, Engagement and Delivery), acan learn from each other.network of research associates coordinated and“These linkages help us to work togetherdirected by UNC Lineberger faculty.more quickly and efficiently to implementStudies show that it takes an average of 17proven interventions and improve systems,”years to implement clinical research results inMelvin explains. “When we work together, wedaily practice.can accomplish more than we can alone, and we“Given the pace of discovery in many areas ofcan do it faster. We hope that NC SPEED cancancer prevention and control, 17 years is justhelp make North Carolina the state thattoo long to wait for patients to benefit from theseexperiences the greatest improvements in cancernew discoveries,” Melvin says. “Activelyoutcomes over the next decade.” Lap-A-Thon supports lung cancer researchA Lap-A-Thon, sponsored by East Chapel Hill High School's Cross Country Team, held January 30 at theschool's track, attracted 200 walkers, jogger and runners, and raised 5,000 for lung cancer research atUNC Lineberger. The event was led by Sam Marks, cross country team co-captain, Coach Steve Marquis, andElsbeth Grant, co-captain. "We organized this event to show support for our teammate and friend, DavidCalderon-Guthe, who recently lost his mother, Rebecca Calderon, to lung cancer and to give others a chance tosupport those still battling their disease," explained Sam Marks. Photo caption: L-R: Elsbeth Grant, KlaraCalderon-Guthe, David Calderon-Guthe, Alison Smith, Claire Gildard, Elliot Schwartz, and Sam Marks.Outcomes Researchcontinued from page 1understanding of patient preferences, thisknowledge can also help inform treatment decisionsthat are best and meet the needs and preferences ofeach individual patient.”Carpenter and Richard Goldberg, MD, associatedirector of UNC Lineberger and physician-in-chiefof the NC Cancer Hospital, are investigatingcolorectal cancer treatment outcomes, in whichtreatment may involve surgery and different types ofchemotherapy. Information from several treatmentoutcomes studies for colorectal and other cancershas documented various side effects, and cansometimes help patients choose the treatment thatavoids the side effects that matter most to them.“These same outcomes studies have informed thedevelopment of new technologies and treatmenttechniques. For example intensity-modulatedradiation therapy and nerve-sparing prostatectomyare prostate cancer treatment options that are moreprecise and typically have fewer side-effects than theprior generation of treatments,” Carpenter explains.Til Stürmer, MD, associate professor ofepidemiology at the UNC Gillings School of GlobalPublic Health and director of the UNC-GSK Centerof Excellence in Pharmacoepidemiology and PublicHealth, studies drug benefits and drawbacks acrossthe population. He is currently focusing ondeveloping new methods to increase validity of nonexperimental treatment comparisons and the role ofcertain pain medications on the occurrence ofcolorectal cancer. “Any knowledge about the causesof cancer will increase our potential to reduce theincidence of cancer through changes in lifestyle andscreening,” he says.And, Carpenter adds, “It allows us to developinformation to help inform treatment decisions forpatients and to help inform the next generation ofresearch.” Jim Bear Named HowardHughes Medical InstituteEarly Career ScientistJames Bear, PhD, associate professor of cell anddevelopmental biology in the UNC School ofMedicine, has been selected as one of only 50researchers in the United States to receive aHoward Hughes Medical Institute Early CareerScientist Award.The institute's Early Career Scientist awardsidentify the nation's best biomedical scientistsat a critical early stage of their faculty careers,and provide them with flexible funding todevelop scientific programs of exceptionalmerit. Bear, a member of UNC Lineberger, willreceive a six-year grant to fund his research intoproteins associated with cell motility andmelanoma.Bear came to UNC in 2003 following apostdoctoral fellowship at MIT. He earned hisundergraduate degree in Biology fromDavidson College in Davidson, NC, and hisdoctoral degree in Cell & DevelopmentalBiology from Emory University. cancerLines Spring 20095

34014 UNC.qxp:CLines9 044/22/097:15 AMPage 7Video Games Help Patients Sit Stillfor Treatment, Move for TherapyIn the new NC Cancer Hospital, the aim is toprovide enhanced amenities to promote patientcare and recovery. To do that, we are setting upa spec

Karen. This year's program featured patient Christina Gianoplus, from Wilmington, NC, who shared her inspiring story of her treatment for colon cancer by Dr. Richard Goldberg, UNC Lineberger associate director. Pictured (left to right) are Shelley Earp, MD, UNC Lineberger director, Richard Goldberg, MD, UNC Lineberger associate director,