Transcription

Roadway Safety Professional Capacity Building (RSPCB)Road Safety Peer Exchange for Tribal GovernmentsAn RSPCB Peer ExchangeIntroduction and BackgroundThis report provides a summary of the proceedings of the Road Safety Peer Exchange for TribalGovernments held in Albuquerque, New Mexico on December 9th and 10th, 2014. The peer exchangebrought together safety practitioners from across the United States to facilitate the exchange ofinformation on road safety and to explore opportunities for collaboration between tribes, the FederalHighway Administration (FHWA), Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), State Departments of Transportation(DOT), Tribal Technical Assistance Program (TTAP) Centers and other government entities on tribalroad safety and safety plans by tribes (see Appendix A for a complete list of attendees).The peer exchange covered the following key topics: Strategies, challenges, and opportunities for reducing fatal and several injury crashes ontribal roads;Developing and implementing safety plans by tribes;Improving safety data and applying the systemic approach to safety;Conducting road safety evaluations and road safety audits;Addressing behavioral safety issues; andExploring new safety partnerships for tribes.Peer Exchange ProceedingsThe format of the Peer Exchange consisted of a series of presentations, roundtable discussions, andbreakout groups (see Appendix B for the complete agenda). At the end of the workshop, participantsfrom each organization were charged with developing a list of key takeaways and action plans fortheir respective tribes or agencies to address the key topics noted above. Key actions included: Assessing the safety needs of tribal governments through stakeholder engagement;Exploring new partnerships between tribes and counties, resource agencies, TTAP Centers,and other government entities;Using safety plans to compete for safety grant funding;Emphasizing the importance of safety plans;Providing tribes with technical assistance to support strong safety plans;Helping tribes overcome staff limitations;Expanding tribal participation in statewide plans;Organizing regional peer exchanges focused on road safety for tribal governments;Developing a glossary of key concepts in road safety for tribal governments; andCreating a clearinghouse for tribal governments of safety resource documents and bestpractice examples.A brief description of the peer exchange proceedings is provided below.ABOUT THE PEEREXCHANGEFHWA’s RSPCB TechnicalAssistance Program supportsand sponsors peer exchangesand workshops hosted byagencies.DateDecember 9 – 10, 2014HostFHWA Office of SafetyParticipantsRepresentatives from:15 tribal entities6 TTAP/LTAP Centers2 State transportation agenciesBureau of Indian AffairsFHWA Federal Lands HighwayDivisionFHWA New Mexico DivisionOfficeFHWA Office of SafetyFHWA Resource CenterFHWA Technology PartnershipProgramsU.S. DOT Volpe CenterFHWA’s Office of Safetysponsors P2P events.Learn more.

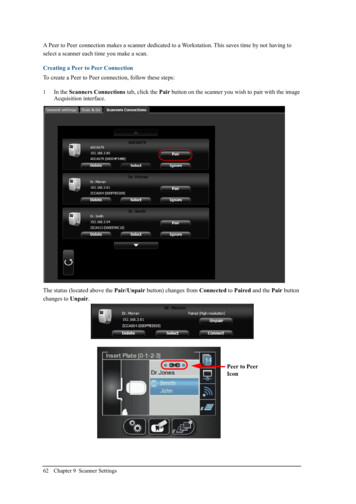

Roadway Safety Professional Capacity Building (RSPCB)Introductory PresentationsWelcoming RemarksNew Mexico DOT (NMDOT) Tribal Liaison Ron Shutiva opened the peer exchange with a brief prayer and remarks. FHWA New MexicoDivision Administrator John Don Martinez and NMDOT District Engineer Larry Maynard then welcomed participants to the peerexchange. The presenters addressed the importance of collaboration and the value of formal agreements between tribes and State,Federal, and local transportation agencies. They also emphasized New Mexico’s strong history of successful partnerships to promotetribal road safety. They introduced the exchange as a valuable opportunity to share nationwide perspectives on tribal road safety and todevelop ideas for effective tribal investment strategies.The FHWA Office of Safety Local and Rural Road Safety (LRRS) Program Manager providedan overview of the workshop event and asked participants to introduce themselves and sharetheir expectations. Expectations included: To develop a list of innovative ideas for improving roadway safety for tribal members;To meet and network with practitioners from the field of roadway safety;To learn about successful examples of tribal safety plans;To brainstorm creative ways for tribal governments to fund road safety improvementsand overcome resource limitations, including inexpensive solutions to roadway safetyissues;To share innovative strategies for gathering and analyzing crash, traffic, and roadwaydata;To focus on safety issues of special concern, including roadway departures, bicycleand pedestrian safety, and distracted/impaired driving;To discuss the role of stakeholders from each of the “4 Es” of safety: Engineering,Enforcement, Education, and Emergency Medical Services (EMS);To develop a list of training and education needs for TTAP and LTAP Centercustomers; andTo discuss Federal programs with the potential to benefit tribal safety.Tribal Transportation Program OverviewThe FHWA Tribal Transportation Program (TTP) Tribal Coordinator gave an overview of theTTP to inform the conversation of the event.Figure 1: FHWA’s LRRSManager provided anoverview of the event(Photo courtesy of EasternTTAP at Michigan Tech)In accordance with the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21), FHWA allocated over 400 million to tribesannually through the TTP. Approximately two percent of this fund, or roughly 8.5 million, is dedicated to the Tribal TransportationProgram Safety Fund (TTPSF). The TTPSF allocates funding according to four categories that correspond to the “4 Es” of safety. Allmodes of transportation are eligible for funding through the TTPSF.In 2013, FHWA received 126 TTPSF applications totaling 27.2 million. FHWA funded 94 of these applications for a total of 8.6million. Approximately half of this funding supported safety planning efforts. FHWA determines which applications to fund according tothe following selection criteria: use of safety data, connection to a safety plan, use of a comprehensive approach to safety, availabilityof matching funds (not required), road ownership (for engineering funds only), and connection to an engineering safety study (forengineering funds only). FHWA will announce the 2014 TTPSF funding decisions by early 2015. The call for 2015 TTPSF applicationsis also expected in early 2015.National Tribal Transportation Facility Inventory (NTTFI) and the Road Inventory Field Data Systems (RIFDS)A representative of the BIA Division of Transportation presented an overview of the National Tribal Transportation Facility Inventory(NTTFI) and the Road Inventory Field Data Systems (RIFDS).Road Safety Peer Exchange for Tribal Governments, December 2014Page 2

Roadway Safety Professional Capacity Building (RSPCB)The NTTFI is an inventory of roads and other transportation facilities that serve tribal communities. The inventory includesapproximately 157,000 miles of roads and several thousand bridges, as well as docks, ferry terminals, transit buildings, maintenancebuildings, trails, and other facilities. Facilities included in the inventory are eligible for funding through the TTP. The TTP, which evolvedfrom the former Indian Reservation Roads program, provides funding for all facility types, not just roads and bridges.The BIA manages the NTTFI through the RIFDS. The agency is currently making changes to the RIFDS to improve program oversightand management, and to make the inventory more easily compatible with geographic information systems (GIS) software.Ownership of the NTTFI is complex. Within the inventory, the BIA owns 31,200 miles of roadways, tribes own 26,400 miles, StateDOTs own 22,900 miles, city governments own 2,900 miles, county governments own 65,900 miles, and other Federal agencies own5,200 miles. Although the criteria for inclusion in the inventory are broad, NTTFI facilities must allow public access and should beincluded in the relevant safety plan and long-range transportation plan.TTAP Center Safety PerformanceA representative from the FHWA Office of Technical Services’ Technology Partnership Program (TPP) provided an overview of thenational Local and Tribal Technical Assistance Program (LTAP/TTAP), which includes seven regional TTAP Centers across the UnitedStates. The mission of the TTAP program is to improve the quality of surface transportation through interactive relationships with tribes.TTAP Centers focus their efforts on four focus areas: infrastructure management, workforce development, organizational development,and safety.The TTAP Centers provide technical assistance on a range of topics including road safety audits (RSAs), tribal safety plans, crash dataanalysis, safety tools, safety plans, and safety summits. The seven TTAP Centers offered a total of 87 training sessions in 2013. Inaddition to training, the TTAP Centers work to build a culture of safety in Indian country through communication activities such asnewsletter articles, blogs, and best practices documents. The TTAP Centers also coordinate activities among tribes and help connectthem to Federal, State, and local safety experts. One goal of this exchange was for the participating TTAP Centers to receive feedbackfrom tribal entities to help them enhance the technical assistance that they provide to their customers.Systemic Approach to SafetyA representative from the FHWA Resource Center provided an overview of the systemic approach to safety. Although the systemicapproach to safety offers advantages to any and all transportation agencies, it is particularly effective for rural and tribal roads. While57 percent of fatal crashes in the U.S. occur on rural roads, they do not generally occur at the same location repeatedly. The lowdensity and randomness of crashes on tribal and rural roadways is a challenge to effective safety planning. However, the systemicapproach to safety can help overcome this challenge.The systemic approach to safety emphasizes the importance of crash type and infrastructure. Often, the analysis of crash type, such ashead-on crashes or roadway departure crashes, reveals patterns that can be used to make effective safety improvements. In light ofthis fact, the systemic approach to safety prioritizes safety improvements based on high-risk roadway features that are correlated withparticular crash types. While effective, systemic safety planning should complement site-specific analysis, which identifies opportunitiesfor safety improvements at high-crash locations, or “hot spots.”The key benefit of systemic safety planning is that it increases the potential to reduce severe crashes utilizing low cost safetycountermeasures. This is because systemic safety planning can help tribal entities prioritize limited safety funding and implementproducts with the highest benefit-cost ratio. Another advantage of the systemic approach is that it can help compensate for limited data,because it acknowledges that crash locations alone are not always sufficient to prioritize projects effectively. The systemic approachalso demonstrates that proactive safety improvements are being made, which can help manage risk for tort liability.There are several resources to support the implementation of the systemic approach to safety. FHWA’s Systemic Safety ProjectSelection Tool, for example, helps agencies apply this approach. The National Cooperative Highway Research Program Report 500Series and the Highway Safety Manual offer excellent insight into this approach. Case studies on the use of systemic approach, suchas the TR News article that highlights the Wind River Indian Reservation’s work with the Wyoming LTAP Center, provide additionalexamples of the systemic approach in action. The Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) and FHWA’s CrashRoad Safety Peer Exchange for Tribal Governments, December 2014Page 3

Roadway Safety Professional Capacity Building (RSPCB)Modification Factors (CMF) Clearinghouse also provide suggestions for effective safety countermeasures that can be appliedsystemically.Road Safety AuditsA representative from the FHWA Resource Center presented an introduction to road safety audits (RSAs). An RSA is a formal safetyperformance examination of an existing or future road or intersection by an independent, multi-disciplinary RSA team. RSAs follow an8-step process. To begin, the design team or project owner identifies projects and selects the independent RSA team. Together theproject owner and RSA team hold a start-up meeting to set expectations for the RSA. Then, the RSA team performs field reviews,conducts analysis of key safety elements, and considers solutions that may help resolve safety issues. Next, the RSA team prepares asummary report and presents findings to the project owner. After the RSA team presents the report, the project owner then prepares aformal response. The project owner typically accepts or agrees to consider the suggestions from the RSA team and then incorporatesthe findings into safety actions.Three common concerns with RSAs are time, cost, and liability. However, the RSA process is not necessarily lengthy, and tribes maybe able to minimize the costs of RSA by working with partners. Furthermore, RSAs can actually reduce a tribe’s liability bydemonstrating that the tribe has proactively identified safety needs and made a plan to improve safety. Even if a tribe does not havethe available funding to incorporate the recommendations from an RSA, developing a prioritized list of safety projects can be a usefuldefense in tort liability cases. Additional information on RSAs is available on the FHWA Road Safety Audit Webpage.Developing Safety Plans by TribesThe FHWA TTP Tribal Coordinator presented an introduction to Strategic Highway Safety Plans (SHSP) and safety plans by tribes.Since SHSPs became a requirement for State DOTs there has been a significant reduction in crashes nationwide. Although SHSPs arenot the only cause of this trend, safety plans can make major contributions to the reduction of fatalities and serious injuries onroadways. The two purposes of safety plans are to direct safety programs and to help agencies obtain funding for strategic safetyimprovements.A safety plan is a document that communicates the story of transportation safety needs in a community and how a tribe will addressthese safety needs. Tribes can use TTPSF funding to support safety planning efforts, among other activities. In order to use TTPSFfunding, tribal safety plans must meet several minimum requirements: they must be data-driven, they must involve coordination withstakeholders, they must be coordinated with the State SHSP, they must prioritize a list of strategies, and they must address multidisciplinary safety issues.FHWA’s Strategic Transportation Safety Plan Toolkit for Tribal Governments offers several resources for tribes as they complete safetyplans. The toolkit includes: a safety plan template; a list of State DOT contacts and potential data sources; a draft request for proposals(RFP) for consultant services to help complete a plan; a recorded webinar on tribal safety planning; and many other resources. Thetoolkit also presents the six-step strategic process for tribal safety planning: establish leadership; analyze safety data; determineemphasis areas; identify strategies; prioritize and incorporate strategies; and evaluate and update the plan. The safety plan templateavailable on the toolkit website provides additional information on each step of this process, as well as tips for collecting data,conducting community surveys, selecting safety emphasis areas, identifying safety strategies, and implementing safety plans. In early2015, FHWA will release a new Tribal Transportation Planning Module that will offer additional information on the process ofdeveloping safety plans for tribes.Road Safety Peer Exchange for Tribal Governments, December 2014Page 4

Roadway Safety Professional Capacity Building (RSPCB)Noteworthy Practices from Tribal PresentationsRepresentatives from several of the participating tribal entities offered brief overviews of their safety efforts, emphasizing challengesand best practices associated with road safety evaluations, safety plans by tribes, and behavioral safety. Examples of noteworthypractices highlighted by participants included: The Cheyenne & Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma are two separate tribes in Oklahoma with a combined population of 12,000residents. In recent years, the number of tribal members with valid drivers’ licenses has decreased, as revealed by the smallpool of eligible applicants for employment for roads and transit programs. In response to this issue, the tribes conductedresearch with the goal of determining why, how, and when tribal members lost their licenses. The tribes determined that highschool-age drivers often lost their licenses due to impaired driving charges or other legal issues, and that some young driversnever obtained driver’s licenses due to financial limitations. In recognition of this problem, the tribes set about identifying asolution that would expand the availability of licenses and help unlicensed drivers regain their ability to drive legally. To kick offthis effort, the tribes organized the new “Safe Driver Program” in partnership with adult education programs, employmentopportunity and training services programs, tribal youth programs, and other partners. The Safe Driver Program set a goal ofincreasing the number of legal drivers through strategies such as providing transportation to the Department of Motor Vehiclesand hiring a driver’s education instructor. Overall, the tribes aim to create a program that will help drivers safely regain theirindependence and expand access to employment opportunities for tribal members. The Karuk Tribe, located in Northern California, received a 2013 TTPSF planning grant for 12,500. With this funding, andwith the assistance of FHWA, the Karuk Tribe drafted an RFP to identify a consultant to help develop the Karuk TribeTransportation Safety Study. The mission of the Karuk Tribal Transportation Safety Study was to provide safer conditions formotorists, bicyclists, and pedestrians traveling in the vicinity of Tribal lands. The safety study sought to address key safetyissues on the reservation, including speeding, landslides, flooding, and unsafe conditions for motorists, bicyclists, andpedestrians. As part of the safety study, the Tribe conducted a survey of tribal members’ safety concerns, which includedpotholes, road conditions, reckless driving, bicycle and pedestrian facilities, speeding, and warning signs. To resolve thesafety issues identified through the surveys and through data analysis, the Karuk Tribe selected emphasis areas andprioritized specific safety projects. Finally, the Tribe developed a detailed matrix for each emphasis area and priority project.The matrix identifies strategies, outputs, responsible parties, completion dates, performance measures, and amonitoring/evaluation plan for each emphasis area. Using information from the safety study, the Karuk Tribe was able to applyfor additional funding from the TTPSF to help implement the safety projects identified in the plan. The La Jolla Band of Luiseño Indians in Southern California is a small tribe that has developed a number of transportationplans, including: a Reservation Community Master Plan, a Tribal Transportation Safety Plan, and an Active TransportationPlan. As part of these various plans, the La Jolla Tribe has conducted several roadway assessments, including an activetransportation assessment and a Healthy Communities assessment. For the active transportation assessment, the Tribepartnered with the San Diego Association of Governments (SANDAG) to distribute community surveys and interview firstresponders regarding active transportation and pedestrian concerns. To support these planning efforts, the La Jolla Tribeconducted an RSA in conjunction with a number of partner agencies. The Tribe incorporated the findings of the RSA into theLa Jolla Strategic Transportation Safety Plan 2014. The safety plan allowed the Tribe to compete successfully for funding froma variety of sources, including: the State of California State Transportation Agency (CalSTA) Active Transportation Program,through which the Tribe was awarded 4.1 million for the installation of bike corrals, new signage, bus stops, and walkingpaths. As a result of these planning and assessment efforts, the Tribe has learned that strong, quantitative assessments canhelp tribes vie for competitive grant funding, and that communicating with tribal law enforcement and community members isan effective way to gather information to prepare assessments. The Muscogee (Creek) Nation, like many tribal entities in Oklahoma, has unique safety needs and a distinctive tribal safetyplan. Prior to completing the plan, the Muscogee Creek Nation’s primary safety concerns were school zone safety forpedestrians and natural disaster response routes. Cross Timbers Consulting assisted with safety planning efforts for theMuscogee Nation, as well as five other tribal entities in Oklahoma: the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, the Otoe-Missouria Tribe,Road Safety Peer Exchange for Tribal Governments, December 2014Page 5

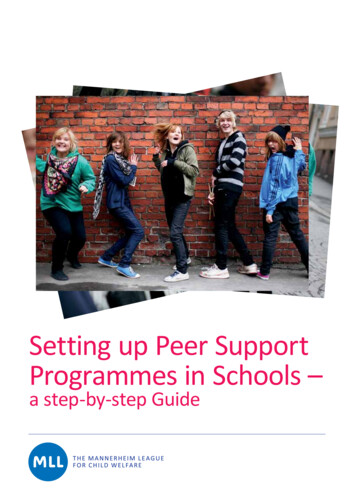

Roadway Safety Professional Capacity Building (RSPCB)the Osage Nation, the Eastern Shawnee Tribeof Oklahoma, and the Miami Tribe ofOklahoma. Each of these six safety plans(available on the Southern Plains TTAPwebsite) reflects the unique values andresources of each individual tribe, even asthey work toward a common goal ofeliminating deaths on tribal roads. The Navajo Nation Division ofTransportation’s Department of HighwaySafety is preparing a safety plan with a strongemphasis on communications and outreach.The safety plan will draw upon data andinformation from the Navajo TTIP, the IndianHealth Service (IHS), the Web-based InjuryStatistics Query and Reporting SystemFigure 1: Meeting participants heard a series of presentations(WISQARS), State TIPs, previous RSAs, andfrom tribal entities and identified a number of best practices.FARS. Through analysis of these data, the(Photo courtesy of Eastern TTAP at Michigan Tech)Division of Transportation was able to identifycorridors with high levels of animal-vehiclecollisions and develop strategies for preventing animals from entering the roadway. The Navajo Nation is also undertaking aGIS safety data integration pilot project in which the Arizona Department of Transportation and the Navajo Nation are workingtogether to integrate GIS layers and crash data for use in future RSAs on the Navajo Nation. After the GIS safety data pilot iscomplete, the Navajo Division of Transportation is planning to apply the systemic approach to safety throughout the NavajoNation Roadway System. The Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma Department of Transportation and Safety (PNDOTS) strives to maintain the safety andintegrity of roadways and bridges, while continuing to plan and progress the growth of the Pawnee Nation. One of the Tribe’smost significant safety issues in recent years was the need to provide safe pedestrian access from a large housing authority tothe tribal complex. In order to improve conditions for pedestrians, the Tribe constructed a pedestrian bridge and began theconstruction of a safer pedestrian walkway into the tribal complex. In addition to these pedestrian safety concerns, thePNDOTS recently conducted an RSA with the help of the Southern Plains TTAP Center. In 2013, the Pawnee Nation alsoapplied for and received a TTPSF grant to develop the Pawnee Nation Transportation Safety Management Plan. With supportfrom the Southern Plains TTAP Center, the PNDOTS held a community safety workshop in February 2014 that identified threekey safety issues for the Tribe. Specifically, the workshop identified sight distance issues within a school zone, the need fornew emergency response communications equipment, and the need for a safer railroad crossing.Road Safety Peer Exchange for Tribal Governments, December 2014Page 6

Roadway Safety Professional Capacity Building (RSPCB)Noteworthy Practices from Roundtable Discussions and Breakout GroupsThe presentations from the tribal entities were followed by a series of facilitated roundtable discussions on topics such as safety data,bicycle and pedestrian safety, project selection and implementation, and funding safety projects. A brief summary of noteworthypractices and resources identified during these discussions is provided below.Safety Data The Guide for Effective Tribal Crash Reporting: This recently-released resource from the Transportation Research Board(TRB) can help tribes conduct self-assessments for improving data. The goal of this resource is to present the state of thepractice for tribal crash reporting, suggest next steps for improvements, and offer information on available resources from theFederal government. Partnering with EMS: The Karuk Tribe offered a best practice example of partnering with EMS providers to fill in gaps indata. Specifically, the Karuk Tribe worked with local medical and fire departments to collect data on crashes and crashresponse. These EMS services shared incident reports that revealed information on crashes, which the Karuk Tribe was ableto use to map and categorize by crash type. This data facilitated the development of the Tribe’s safety plan. Working with Tribal Police: The Navajo Nation provided an example of partnership with tribal law enforcement agencies.Specifically, the Navajo Division of Transportation worked with the police to extract data from crash reports that revealed crashcharacteristics such as cause, severity, driving direction, age, and roadway ownership. The Navajo Division of Transportationwas able to pull this information into a spreadsheet and integrate the data into GIS to create a map of crash locations. TheNavajo Nation is also working to integrate geospatial crash data from EMS providers, State DOTs, and local governments inorder to implement the systemic approach to safety on tribal roads. Partnering with State DOTs: The Inter Tribal Council of Arizona is working with the Arizona Department of Transportation toobtain information that tribal law enforcement agencies can use to supplement existing data. The Inter Tribal Council is alsohelping small- and medium-sized tribes to develop crash data monitoring systems. Collecting Information through Community Meetings: The Alaska TTAP Center explained that safety plans in Alaska oftenrely on information collected through community meetings. While there may be data available on State-owned roads in tribalareas, tribes sometimes use stakeholder meetings to gather supplemental information on tribally-owned roads. Thesestakeholders include local and regional transportation officials, medical officials, public safety staff, and the general public.One way to collect information from these stakeholders is to provide them with a map of tribal roads and ask them to placestickers on locations where there have been crashes or close calls. Traffic Records Coordinating Committees: The Inter Tribal Council of Arizona is active in Arizona’s Traffic RecordsCoordinating Committee (TRCC). Through its involvement in the TRCC, the Inter Tribal Council is aware that funding isavailable from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) for data improvement activities. Although manytribal and local governments may not have the servers and other technology necessary to make crash data improvements,software may be available through a State’s TRCC that can support these improvements. Data on Fatal Crashes: All State DOTs are required to submit data on fatal crashes to NHTSA’s Fatal Accident ReportingSystem (FARS). However, this database may not include data for all fatalities on tribal lands, particularly in cases where BIAor tribal law enforcement agencies do not report fatalities to the State DOTs. One way for tribes to use FARS data is throughthe website “SafetyRoadMaps.org,” which allows users to sort through five years of FARS data. The Centers for DiseaseControl and Prevention (CDC) also provides another useful tool – WISQARS – that allows users to analyze death certificatedata according to characteristics such as cause, age, and ethnicity.Road Safety Peer Exchange for Tribal Governments, December 2014Page 7

Roadway Safety Professional Capacity Building (RSPCB) BIA Indian Highway Safety Program (IHSP): As a focal point for highway safety issues in Indian country, the IHSP providesservices to all Federally-recognized tribes. The IHSP provides leadership by developing, promoting, and coordinatingprograms that influence tribal and public awareness of all highway safety issues. Tribes can submit applications for IHSPfunding to support safety efforts. Tribes are encouraged to use crash data, citation data, and other data sources to helpidentify the problems they would like to address. This program also offers grant funding to support data collectionimprovement efforts. California Statewide Integrated Traffic Records System: Several tribes noted the possibility of using the CaliforniaStatewide Integrated Traffic Records System (SWITRS) to access crash data and other valuable information. However, sometribes expressed concern that tribal law enforcement agencies are unable to input crash data into SWITRS, and that thesystem may not be accessible to all tribes.Bicycle and Pedestrian Safety Wild Animals: Some tribes in rural areas face unique pedestrian safety issues related to wild dogs, reptiles, and otheranimals. To prevent animal attacks on pedestrians, tribes such as the La Jolla Tribe undertake trail grooming activities. Whileoff-road trails are not traditionally considered the responsibility of transportation officials, many tribes now consider trails to bepart of their multimodal transportation networks. Effective Safety Countermeasures: Several tribes offered information o

A brief description of the peer exchange proceedings is provided below. ABOUT THE PEER EXCHANGE FHWA's RSPCB Technical Assistance Program supports and sponsors peer exchanges and workshops hosted by agencies. Date . December 9 - 10, 2014 . Host . FHWA Office of Safety . Participants . Representatives from: 15 tribal entities . 6 TTAP/LTAP .