Transcription

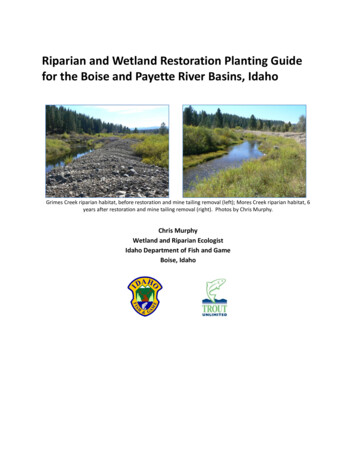

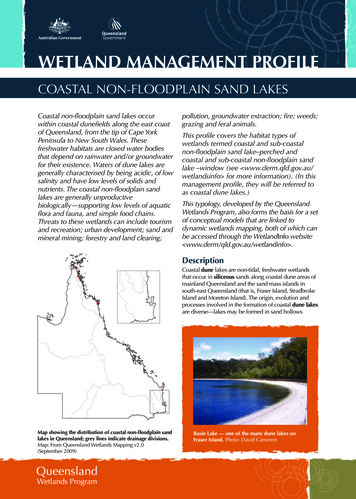

WETLAND MANAGEMENT PROFILECOASTAL NON-FLOODPLAIN SAND LAKESCoastal non-floodplain sand lakes occurwithin coastal dunefields along the east coastof Queensland, from the tip of Cape YorkPeninsula to New South Wales. Thesefreshwater habitats are closed water bodiesthat depend on rainwater and/or groundwaterfor their existence. Waters of dune lakes aregenerally characterised by being acidic, of lowsalinity and have low levels of solids andnutrients. The coastal non-floodplain sandlakes are generally unproductivebiologically—supporting low levels of aquaticflora and fauna, and simple food chains.Threats to these wetlands can include tourismand recreation; urban development; sand andmineral mining; forestry and land clearing;pollution, groundwater extraction; fire; weeds;grazing and feral animals.This profile covers the habitat types ofwetlands termed coastal and sub-coastalnon-floodplain sand lake–perched andcoastal and sub-coastal non-floodplain sandlake –window (see www.derm.qld.gov.au/wetlandsinfo for more information). (In thismanagement profile, they will be referred toas coastal dune lakes.)This typology, developed by the QueenslandWetlands Program, also forms the basis for a setof conceptual models that are linked todynamic wetlands mapping, both of which canbe accessed through the WetlandInfo website www.derm/qld.gov.au/wetlandinfo .DescriptionCoastal dune lakes are non-tidal, freshwater wetlandsthat occur in siliceous sands along coastal dune areas ofmainland Queensland and the sand mass islands insouth-east Queensland (that is, Fraser Island, StradbrokeIsland and Moreton Island). The origin, evolution andprocesses involved in the formation of coastal dune lakesare diverse—lakes may be formed in sand hollowsMap showing the distribution of coastal non-floodplain sandlakes in Queensland; grey lines indicate drainage divisions.Map: From Queensland Wetlands Mapping v2.0(September 2009)Basin Lake — one of the many dune lakes onFraser Island. Photo: David Cameron

created by wind (known as deflation hollows); whendunes advance and form a barrier across hollows andvalleys; or between parallel dunes (that is, in duneswales). These lakes depend on local catchment run-off(rainwater) and/or groundwater and are not consideredto be part of a floodplain. They are generally permanentin nature but may be semi-permanent or temporarydepending on their location and climatic conditions.The water level of coastal dune lakes may change quitemarkedly between seasons.COASTAL dune lakes depend onrainwater and/or groundwater andare generally permanent in nature butmay be semi-permanent or temporarydepending on their location andclimatic conditions. Perched lakes — occur well above sea level and areperched above the water table by an impermeableorganic layer. Lowland lakes on leached dunes — occur in duneswales, near the sea and close to sea level and aretypically associated with swamps. Water table window lakes — occur between dunesand intercept the regional groundwater table. Theyeffectively form a window to the aquifer below. Dune contact lakes—these occur between a sanddune and bedrock. Freshwater lakes with marine contact—these aredistinguished from lowland lakes and dune contactlakes by a current or past connection with the sea. Ponds in frontal dunes—these occur in wind createdhollows in frontal dunes and are often small,shallow and seasonal.Although there is a great deal of variability betweenlake types, the water of dune lakes is generallycharacterised by being acidic (that is a pH of less than6), of low salinity, humic, and having extremely lowlevels of dissolved solids, suspended solids andnutrients. These lakes can be crystal clear, clear andtea-coloured, or even opaque because of the presenceof dissolved organic matter. Water that is tea-colouredor brown is also known as ‘black water’ and this ismore typically found in perched lakes, whereas ‘whiteBasin Lake — one of the many dune lakes onSix main variations of dune lakes have been describedfor the eastern coast of Australia, classified withrespect to their origins, water chemistry andgeomorphology (Timms, 1982; 1986). However, notall dune lakes fit neatly into this classification system.WHAT IS A PERCHED LAKE?Perched lakes are hydrologically complexsystems that can fill rapidly in response to localrainfall and associated infiltration through thesand mass. They are formed in depressionsbounded by a layer of sand that has becomecemented together with decomposed organicmaterial (such as leaves, bark and dead plants).This layer is known as ‘coffee rock’. It is semipermeable to water and prevents rainwater frompercolating through to the regional aquifer, thusthese lakes create their own local groundwatersystems where free water can accumulate in thesoil profile. The topography, stratigraphy(layering), permeability and other properties ofthe local semi-permeable layer can be complexand heterogeneous, making these systems highlydiverse, complex and difficult to predict. They aregenerally more acidic (they have a lower pH)than window lakes because they tend to containmore organic matter. The water level, pH andSunset over Brown Lake on Stradbroke Island—aperched lake. Photo: Nicholas Saunderssize of perched lakes can vary from year to yearor even dry out completely during times ofdrought. Many perched dune lakes are teacoloured because of their high organic content.2

water’ that is clear and colourless arises from regionalgroundwater aquifers—this is more commonlyassociated with window lakes. Factors that contributeto the physical variation between lakes include lakeage and size, how it was formed, proximity to the sea,surrounding vegetation, and the extent to which leaflitter accumulates and decays within it.COASTAL dune lakes generally occurin high rainfall areas, and are orientedwith their long axis aligned in a southeast to north-west direction—in linewith prevailing winds.Coastal dune lakes are usually well oxygenated,naturally oligotrophic (because of low nutrient levelsin the surrounding infertile sands) and unproductivebiologically in that they usually support low levels ofaquatic flora (including algae) and fauna, and supportrelatively simple aquatic food chains. The term‘dystrophic’ is often used to describe tea-colouredperched lakes, and to describe bodies of water thatcontain stained, acid water with low biologicalproductivity. Oligotrophic lakes are unusual both inAustralia and the world in general, even though theywere naturally common in the past. Over time, manylakes have become eutrophic due to the natural lakeageing process and also as a result of human activity.DistributionThe coastal sand dune areas of eastern Queensland,from the tip of Cape York to the New South Walesborder, contain hundreds of freshwater lakes. Most ofthese occur in high rainfall areas and are orientedwith their long axis aligned in a south-east to northwest direction, in line with prevailing winds.Perhaps the most well known coastal dune lakes arethose that occur on Fraser Island in south-eastQueenland. Fraser Island contains over 40 percheddune lakes (for example lakes Birrabeen, Allom,McKenzie, Bowarrady and Benaroon)—half of theworld’s perched dune lakes occur here. LakeBoomanjin on Fraser Island is recognised as theworld’s largest perched lake. In the south-eastQueensland bioregion (bioregion 12) coastal dunelakes are also found on Moreton Island (for exampleBlue Lagoon and Lake Jabiru), Stradbroke Island (suchas Blue Lake, Brown Lake and Tortoise Lagoon), andwithin the Cooloola sand mass (for example Poona,Freshwater and Deepwater Lakes).This profile focuses on the coastal dune wetlands thatare considered to be lacustrine or ‘lake-like’ in form.However, coastal dune lakes do not occur in isolation.They may be fringed by dense stands of sedges(particularly Lepironia articulata), wet heathvegetation, or occur alongside dunal swamps that aredominated by species such as Melaleucaquinquenervia. Further information on thesesurrounding wetland types and how they should bemanaged can be found in the wetland managementprofiles (see www.derm.qld.gov.au/wetlandinfo ).Further north, coastal dune lakes and swamp wetlandsare found in the Dismal Swamp section of theShoalwater Bay dunefield area/Shoalwater BayMilitary Training Area (near Byfield) of the CentralQueensland Coast bioregion (bioregion 8). This area isrecognised for its diverse landscape and vegetationtypes and relatively undisturbed wilderness areas.The tropical dunefields on Cape York Peninsulabioregion (bioregion 3) also contain numerous dunelakes and wetland habitats. These are similar bothbiologically and chemically to the dune lakes ofsouth-east Queensland. However, unlike south-eastQueensland dune lakes, which are situated on deepsand dunes, those in the Cape York Peninsula bioregionare associated with ancient dunes that are thinlycovered with sand and have basement rocks (lateriteand Mesozoic sandstones) close to the surface.Coastal dune lakes can be tea-coloured due to thepresence of dissolved organic matter. Photo: DERM3

Cape York Peninsula dune lakes occur in four mainareas (located from north to south): between Somerset and Ussher Point, around OrfordBay (for example the perched lakes, Lake Wicheuraand Lake Bronto) adjacent to Shelburne Bay, around Olive River around Cape Grenville in the Cape Flattery — Cape Bedford dunefields,north of Cooktown.The Queensland Government has direct responsibilityfor the protection, conservation and management ofwetlands in Queensland, a responsibility shared withlocal government and the Australian Government (forsome wetlands of international significance). Theseresponsibilities are found in laws passed by theQueensland parliament, laws of the Commonwealth,international obligations and in agreements betweenstate, local and the federal governments. Moreinformation on relevant legislation is available fromthe WetlandInfo website www.derm.qld.gov.au/wetlandinfo .The WetlandInfo website provides in-depth data,detailed mapping and distribution information for thiswetland habitat type.National conservation statusThe coastal dune lakes of Queensland are widelyrecognised and valued at the state, national andinternational level. Many of the coastal dune lakes arefound in three of the five Queensland sites recognisedas Wetlands of International Importance under theRamsar Convention (Ramsar wetlands)—Shoalwaterand Corio Bays Area, Great Sandy Strait and MoretonBay. In addition Fraser Island, which is on the WorldHeritage List, maintained by the World HeritageConvention, is recognised as being the largest sandmass island in the world and contains over 40perched lakes and numerous other lakes. TheShoalwater Bay Military Training Area (Byfield) is aCommonwealth heritage place under theCommonwealth Heritage List.Sach Waterhole is an example of a coastal dunelake on Cape York Peninsula. Photo: John NeldnerRamsar wetlands, World Heritage properties,Commonwealth heritage places, threatened species,and migratory species are listed as matters of nationalQueensland status and legislationWetlands have many values – not just for conservationpurposes – and the range of values can vary for eachwetland habitat type and location. The QueenslandGovernment maintains several processes forestablishing the significance of wetlands. Theseprocesses inform legislation and regulations to protectwetlands, for example, the status assigned to wetlandsunder the regional ecosystem (RE) framework.A comprehensive suite of wetlands assessment methodsfor various purposes exists, some of which have beenapplied in Queensland. More information on wetlandsignificance assessment methods and their applicationis available from the WetlandInfo website www.derm.qld.gov.au/wetlandinfo . Queensland hasalso nominated wetlands to A Directory of ImportantWetlands of Australia (DIWA), see the appendix.Lake Birrabeen is a coastal dune lake on FraserIsland—a World Heritage Area, renowned for itsmany dune lakes. Photo: DERM4

environmental significance (NES) under theCommonwealth Environment Protection andBiodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) and assuch, are afforded protection under the Act. The EPBCAct recognises all species listed under the JapanAustralia and China-Australia Migratory BirdAgreements (JAMBA/CA MBA respectively) and/or theBonn Convention (see Species of conservationsignificance and Appendix 2). Any action that will, oris likely to, have a significant impact on a NES matterwill be subject to an environmental assessment andapproval regime under the Act.within these areas include burials, ceremonial eartharrangements, pathways, scarred trees, hearths, shellmiddens, quarries, stone scatters, fish traps, food andfibre resources and historic contact sites. Some coastaldune lake areas have particular significance as storyplaces, landscape features and as sites for culturalactivities.The most commonly recorded sites associated withcoastal dune lakes are shell middens and stoneartefact scatters associated with open campoccupation sites. Archaeological evidence of culturalactivity, such as shell middens and stone artifactscatters, are often concentrated along ecotonesaround the margins of coastal dune lakes, and inassociation with neighbouring regional ecosystems.The clustering of sites along ecotones reflects theconcentration of traditional occupation and usewithin areas of greatest biodiversity.There are at least eight fauna species associated withcoastal dune lakes in Queensland that are listed asthreatened under the Queensland NatureConservation Act 1992 (NC Act) and/or the EPBC Act,and/or on the IUCN Red List (see Appendix 2).Recovery plans, which set out research andmanagement actions, to support the recovery of someof the threatened species listed in Appendix 1 may beavailable or being prepared.Some coastal dune lakes also have historic culturalheritage significance of both Indigenous and nonIndigenous origin, although most have not beensurveyed or assessed for historic heritage values.DERM has records of six historic sites associated withcoastal dune lakes, all located within the Cooloolaand Fraser Island areas. The historic heritage values ofcoastal dune lakes demonstrate evidence of their pastoccupation and use associated with the pastoral,timber and forestry industries. Sites include timbercamps, a homestead, loading jetty, sawmill andsettlement and an historic landscape area. For furtherinformation refer to the Coastal fringe wetlands—cultural heritage profile www.derm.qld.gov.au .Management plans or similar documents are in placefor each of the Ramsar wetlands, although in someinstances they may not apply to the entire Ramsar site.SOME coastal dune lake areas are ofparticular significance to Indigenouspeople as story places, landscapefeatures and as sites for culturalactivities.Cultural heritageAll wetland ecosystems are of material and culturalimportance to Indigenous people and many will haveprofound cultural significance and values. More than100 Indigenous cultural heritage sites have beenrecorded within coastal dune lakes in Queensland—concentrated on Stradbroke, Moreton and FraserIslands and coastal dune areas at Cooloola insoutheast Queensland and Cape Flattery, in NorthQueensland. However, most coastal dune lakes havenot yet been systematically surveyed or assessed forcultural heritage significance.Archaeological evidence of occupation (such asshell middens) may be found in dunal areas—often concentrated along the margins of lakes.Photo: DERMThere is a high likelihood of cultural heritage sitesoccurring within and adjacent to coastal dune lakes.Evidence of traditional occupation and use recorded5

Ecology and ecological valuesCoastal dune lakes within Queensland are diverse insize, form, depth and degree of permanency (that is,seasonally drying to permanent). Given that theyoccur from the tip of Cape York Peninsula to NewSouth Wales, and beyond, a diverse range of flora andfauna species are supported by these habitats. In theirnatural state coastal dune lakes can support bothspecialised animal species that survive in the lownutrient, acidic water characteristic of dune lakes,and/or animals that are widespread and tolerant of awide range of conditions. Differences in speciescomposition between lakes are due to theirgeographical isolation from each other and may occuropportunistically (for example the chance arrival of aparticular fish species).Coastal dune lakes and their surrounding wetlands area unique and aesthetically valued component of theQueensland landscape and provide ecosystemservices that include: regulating services — including sediment andnutrient retention cultural services — such as Indigenous culturalvalues and sites, tourism and recreation supporting services — such as being important ashabitat for fauna at a particular stage of their lifecycle (for example, breeding) provisioning services — dune lakes and theirsurrounding dunes are a source of groundwater andresources (for example sand and minerals).In general, coastal dune lakes are considered to beunproductive biologically in that they are naturallyoligotrophic, have low concentrations of essentialplant nutrients, are high in dissolved oxygen andsupport relatively low amounts of aquatic plants(including algae) and animals. Oligotrophic lakes areoften surrounded and if shallow, invaded by densestrands of sedges and rushes such as Lepironiaarticulata, Eleocharis spp., Baumea spp., Schoenusspp., Juncus spp. and Gahnia spp. The deeper areasof lakes are generally vegetation free. ThroughoutQueensland L. articulata is commonly associated withDUNE lakes can support specialisedanimal species that survive in lownutrient, acidic water and/or speciesthat are widespread and tolerant of awide range of conditions.COASTAL DUNES AND SAND MASSES CONTAIN LARGE QUANTITIES OF WATERCoastal dunes and sand masses are an importantsource of groundwater and most coastal dunelakes (particularly window lakes) are dependenton groundwater for their formation. The source ofthis groundwater is the dunes and sand massesthemselves, which hold vast quantities offreshwater (from rain) in groundwater aquifers.For example, Fraser Island which has sand dunesup to 220 m above sea level contains a massivegroundwater aquifer that stores an estimated 10to 20 million megalitres (ML) of water, of whichalmost 6 million ML is above sea level. Watercan remain in a sand mass for many years,sometimes as long as 70 to 100 years. Where theground surface dips below the watertable, theexposed groundwater forms a window lake.Aquifers play an important role in preventingsaltwater from the ocean seeping intoSand dunes hold vast quantities of water ingroundwater aquifers. This groundwater playsan important role in maintaining the ecologicalintegrity of dunes. Photo: DERMgroundwater and the land itself. It does thisbecause gravity from the groundwater moundexerts an outward pressure on seawater andfreshwater naturally floats on top of saltwater.6

coastal dune lakes. However, species such as Baumeateretifolia, Eleocharis sphacelata, Leptocarpus tenax,which are common in south-east Queensland, aremore commonly replaced with the speciesB. rubiginosa, E. brassi and Dapsilanthus ramosus inCape York coastal dune lake areas (Timms, 1986).of aquatic invertebrates and both food and shelter forhigher order organisms such as fish, frogs and turtles.Damage to this vegetation is likely to be detrimentalto the feeding and breeding activities of thethreatened fish species, the honey blue eyePseudomugil mellis (Arthington, 1994). This speciesextends only as far north as the Shoalwater Bayregion. Food sources for coastal dune lake-dwellingorganisms may be either allochthonous (that isexternally derived) or autochthonous (internallyderived). Three simple food webs have been describedfor coastal dune lakes (Arthington, 1994). Theseinclude a:Coastal dune lakes can occur alongside a diverserange of wetland habitats and vegetation typesincluding beaches, mangroves, salt flats, swamps,sedgelands, heathland and rainforest depending ontheir exact location. Where lake levels fluctuate,vegetation surrounding the lake is highly watertolerant and may include species such as sundews(genus Drosera) and bladderworts (genus Utricularia).1) grazing food chain — this involves phytoplanktonbeing grazed by zooplankton, and zooplanktonbeing grazed by fish and/or turtlesLittoral vegetation, which is vegetation that occursaround the lake’s edge, provides habitat for a variety2) detritus food chain—whereby dissolved humicacids (from leaves and other organic matter)provide nutrients for bacteria, which in turn feedzooplankton and fish3) terrestrial organic food chain—in this caseallochthonous food sources in the form of pollenor insects provide food for fish directly.Studies have shown that human activities on FraserIsland can influence the relative importance ofallochthonous and autochthonous carbon sources fordune lake consumer organisms (that is, invertebratesand fish) (Hadwen & Bunn 2004, 2005).Some coastal dune lakes do not contain fish, andwhere this is the case, food chains may be even simplerwith aquatic insects (of the Orders Hemiptera,Odonata, Coleoptera, Chironomidae) being the top ofthe food chain. Coastal dune lakes support largepopulations of invertebrates, most notably the copepodCalamoceia tasmanica, which is a species ofzooplankton characteristically associated with theseecosystems.ALTHOUGH the lakes are not overlyproductive in terms of vegetationbiomass they are an important seasonalrefuge for birds as they move from dryinland areas or during times of drought.Coastal dune lakes are often surrounded andinvaded by grass-like vegetation. Photos: DERM7

The coastal dune lakes and surrounding swamps andsedgeland provide important habitat for a variety ofspecies including rare and threatened ones (see Speciesassociated with coastal dune lakes). Although the lakesare not overly productive in terms of vegetationbiomass, they provide an important seasonal refuge forbirds, including migratory species, as they move fromdry inland areas or during times of drought.Coastal dunes lakes are highly susceptible to pollutionand nutrient enrichment. Nutrient enrichment mayresult from urban runoff, sewage, agriculturalactivities, clearing and/or burning and in response torecreational use (see Managing coastal dune lakes).The northern sedgefrog Litoria bicolor is found incoastal dune lake areas of northern Queensland.Photo: DERMDESCRIBING THE NUTRIENTSTATUS OF LAKESLakes are often classified according to theirnutrient or trophic status. Oligotrophic lakes,like healthy coastal dune lakes, arecharacterised by having low levels of nutrients(such as phosphorus and nitrogen) and plantgrowth and high oxygen concentrations, whileeutrophic lakes have high levels of nutrients andplant growth and low oxygen concentrations.Between these extremes are mesotrophic lakes.Factors that contribute to the nutrient status ofa lake include:The water of coastal dune lakes is often clear andlow in nutrients and algae. Photo: DERM climate—this includes temperature, amountof sunlight, rainfall and hydrology of the lake lake morphometry—this is based on thedepth, volume and surface area of the lake,and the lake surface area to catchmentsize ratio nutrient supply—dependent on soil type,geology of the landscape, vegetation, andland use and management.Eutrophic lakes are also susceptible to algalblooms—a condition where the number of algalcells has increased to such an extent that waterquality is reduced. Algal blooms can discolourwater, form scums on the lake surface and produceunpleasant odours. While they are not always toxic,algal blooms can also harm aquatic life (such asfish and frogs) and be a human health issue.The process by which a lake moves from anoligotrophic to eutrophic condition is knownas eutrophication. Lakes that occur incatchments that have rich organic soils oragricultural areas enriched with fertilisers arelikely to be more eutrophic than those thatoccur on infertile soils or sand dunes.Since harmful algal blooms can have detrimentaleconomic, environmental and social impacts theQueensland Government has developed amultiagency response plan to aid State and localgovernments and water storage operators managethem (find more information on the DERM website www.derm.qld.gov.au ).8

FishSpecies associated with coastaldune lakes– Oxleyan pygmy perch Nannoperca oxleyana (S)Preservation of coastal dune lakes is vital to protectspecies that are dependent on these wetlands for nesting,breeding and/or feeding habitat, particularly speciesthreatened with extinction. A number of speciesassociated with Queensland’s coastal dune lakes arelisted as threatened under State (NC Act) andCommonwealth (EPBC Act) legislation and/or recognisedunder international conventions or agreements such asthe IUCN Red List. Some of the species associated withcoastal dune lakes are listed below.– honey blue eye Pseudomugil mellis (S,)– ornate rainbowfish Rhadinocentrus ornatus (S)– poreless gudgeon Oxyeleotris nullipora (N)– onegill eel Ophisternon bengalense (N)– northern purplespotted gudgeon Mogurndamogurnda (N)Amphibians– wallum froglet Crinia tinnula (S)Note: Fauna and flora species more commonly orexclusively occurring in northern or southernQueensland are denoted by an (N), or (S) respectively,after the species name.– Cooloola sedgefrog Litoria cooloolensis (S)– wallum rocketfrog Litoria freycineti (S)– wallum sedgefrog Litoria olongburensis (S)WetlandInfo provides full species lists of wetlandsanimals and plants.– northern sedgefrog Litoria bicolor (N)– white lipped treefrog Litoria infrafrenata (N)Fauna– shrill whistlefrog Austrochaperina gracilipes (N)Birds– tawny rocketfrog Litoria nigrofrenata. (N)– ground parrot Pezoporus wallicusTHE HONEY BLUE EYEThe vulnerable (NC Act) honey blue eyePseudomugil mellis fish is endemic toQueensland, occurring in slow flowing, slightlyacidic, tannin-stained coastal dune lakes as wellas streams, swamps and heath areas of southeast Queensland, extending north as far asShoalwater Bay. It is often found within or nearemergent or submerged sedge and rushvegetation (for example, Lepironia articulata,Gahnia seiberiana, Juncus spp., Eleocharis spp.).At 3 cm long, it is one of the smallest threatenedspecies in Queensland. In addition to itscharacteristic blue eyes, the honey blue eye is adistinctive amber to orange colour.Honey blue eye Pseudomugil mellis.Photo: Gunther SchmidaHabitat protection is vital for ensuring survival ofthe honey blue eye. It is also important tomaintain genetic diversity of the species byprotecting individual populations and ensuringthat breeding can occur between adjoiningpopulations. Small breeding populations arebeing maintained in captivity.Threats to the honey blue eye include residentialand industrial development, forestry, mining,aquarium use and agriculture. The introducedmosquito fish Gambusia holbrooki also threatensthe species where the two co-exist, because itslarvae compete with it for food and habitat.9

InsectsReptiles– Fraser Island short-neck turtle Emydura macquariinigra (S)– Order Hemiptera– Order Odonata– estuarine crocodile Crocodylus porosus (N)– Order ColeopteraMicrocrustaceans– Order Chironomidae.– Calamoecia tasmanica– Calamoecia ultima (N)ACID FROGSA group of four amphibians called ‘acid frogs’inhabit the temporary or permanent still waters oflakes, creeks and swamps of south-eastQueensland and New South Wales. Thesespecies undergo tadpole development in softwaters of high acidity (low pH) and low nutrientcontent—conditions commonly found in coastaldune lakes and their surrounds.The four acid frog species are the wallum frogletCrinia tinnula, Cooloola sedgefrog Litoriacooloolensis, wallum rocketfrog Litoria freycinetiand wallum sedgefrog Litoria olongburensis.Recent records indicate all of these speciescontinue to occur throughout their pre-Europeanrange. However populations have suffered habitatloss and disturbance because of land clearing.The wallum rocketfrog Litoria freycineti—one of fourfrog species commonly referred to as ‘acid frogs’.Photo: DERMOther potential threats have been identified (forexample the use of chemicals to control mosquitoesand weeds, grazing and predation by feral pigs) butso far their effects have been poorly studied.Acid frogs have specialised breeding requirementsand are particularly susceptible to changes inwater chemistry. Exotic pine plantations with theirassociated road construction, and changes toburning practices have led to alterations inhydrology and water chemistry and these havebeen detrimental to the frogs’ breeding success.The clearing of native vegetation to establishexotic pine plantations has now ceased but habitatloss, a result of increased urban development,continues to threaten acid frog habitat. Damage tomicrohabitats (reed beds and sedges) by toofrequent fire, human trampling and recreationactivities have also been identified as detrimental.A number of actions to protect the habitat of theacid frogs have been identified. These include:establishing minimum protective buffers aroundknown breeding sites (for example, 100 m; refer toManaging alterations to hydrology/drainage) thatexclude a range of routine uses including timberharvesting and chemical use; maintaining naturaldrainage patterns, water tables and water qualitywhen conducting activities adjacent to or upslopeof known breeding sites; and monitoring andmanaging grazing, feral pigs and pine wildings.Handling frogs should be avoided, to reduce therisk of disease transfer.10

ESTUARINE (SALTWATER) CROCODILEThe estuarine crocodile Crocodylus porosus ismost commonly found in the tidal reaches ofrivers and marine habitats from Rockhamptonand north to the Queensland–Northern Territoryborder. However, they are also found infreshwater sections of lakes, lagoons, swampsand

COASTAL dune lakes depend on rainwater and/or groundwater and are generally permanent in nature but may be semi-permanent or temporary depending on their location and climatic conditions. Basin Lake — one of the many dune lakes on Six main variations of dune lakes have been described for the eastern coast of Australia, classifi ed with