Transcription

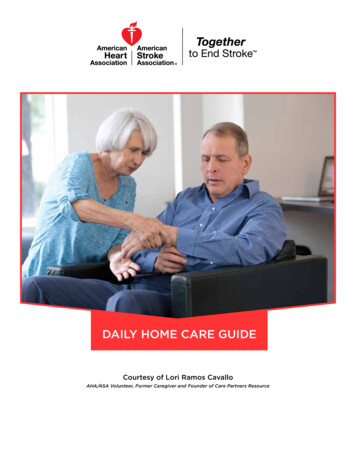

After a loved one dies—How children grieve and how parentsand other adults can support them.

After a loved one dies—How children grieve and howparents and other adults can support them.Written by David J. Schonfeld, MD, and Marcia Quackenbush, MS, MFT, CHESDr. Schonfeld is director of the National Center for School Crisis and Bereavement,which was established by a generous grant from the September 11th Children’s Fundand National Philanthropic Trust. www.schoolcrisiscenter.orgCopyright 2014 New York Life Foundation. Permission is granted for educationalDQG QRQSURƬW XVH RI WKHVH PDWHULDOV ZLWK DFNQRZOHGJPHQW OO RWKHU ULJKWV UHVHUYHG 3XEOLVKHG E\ WKH 1HZ RUN /LIH )RXQGDWLRQ 0DGLVRQ YHQXH 1HZ RUN NY 10010. email: NYLFoundation@newyorklife.com.This publication was supported by a generous grant from the New York LifeFoundation.The information contained in this booklet is not intended as a substitute for yourhealth professional’s opinion or care. You and your children have unique needsthat may not be addressed in this booklet. If you have concerns, be sure to seekprofessional advice.

3URWHFWLQJ IDPLOLHV DQG SURYLGLQJ WKHP ƬQDQFLDO VHFXULW\ LV DW WKH KHDUW RI 1HZ RUN /LIHoV EXVLQHVV %XW ZH DOVR UHFRJQL]H WKH WUHPHQGRXV HPRWLRQDO WROO VXƪHUHG E\ family members—especially children—when they lose a parent, sibling, or otherORYHG RQH QG KHOSLQJ \RXQJ SHRSOH JULHYH KHDO DQG JURZ LV SDUW RI 1HZ RUN /LIHoV long-term philanthropic commitment to assisting children in need.This booklet provides valuable guidance to parents and other caregivers who arehelping children cope with their grief and fear following a death in the family. Prepared with the assistance of some of the nation’s most respected authorities onWKLV LPSRUWDQW WRSLF , WKLQN \RX ZLOO ƬQG WKHLU ZRUGV DQG VXJJHVWLRQV VHQVLEOH DQG reassuring.I wish you the comfort that is found in helping young hearts heal.7KHRGRUH 0DWKDVChairman, President and CEONew York Life

After a loved one dies—How children grieve andhow parents and otheradults can support them.What’s covered in this guide.Helping children, helping the family . 4Why a parent’s role is important . 5Helping children understand death. 5Explaining death to children . 8How children respond to death . 9 WWHQGLQJ IXQHUDOV DQG PHPRULDOV . 13Helping children cope over time . 15Getting help . 18Supporting families who are grieving. 19Taking care of yourself . 20Looking to the future . 21Resources for support . 21

Helping children, helping the family.When childrenget supportfrom parentsand otheradults aroundthem, it helpsthe entirefamily cope.7KH GHDWK RI D ORYHG RQH LV GLƯFXOW IRU everyone. Children feel the loss strongly.Parents are coping with their own grief. Ifa parent dies, the surviving parent facesthe new responsibility of caring for thechildren alone. Grandparents, aunts, unFOHV DQG IDPLO\ IULHQGV DUH DƪHFWHG WRR When children get support from parentsand other adults around them, it helpsthe entire family cope. There is less confusion, and more understanding of oneanother. The family sees that it can stayclose even though the feelings of griefmight be very strong.Because children and teens understandGHDWK GLƪHUHQWO\ IURP DGXOWV WKHLU UHDFWLRQV PD\ EH GLƪHUHQW 6RPH RI WKH things they say or do may seem puzzling.How to use this guide.This guide reviews how children grieveand how parents and other caring adultscan help them understand death better.,W RƪHUV VXJJHVWLRQV IRU KHOSLQJ FKLOGUHQ cope. These suggestions are not meantto rush children through their grief orturn them into adults before their time.Rather, they will give them an understanding they can use now, as children, togrieve in a healthy and meaningful way.This guide covers a lot of information.Some of it will apply to your situation,and some of it may not. You can read justthe sections that seem most importantWR \RX ULJKW QRZ V WKLQJV FKDQJH RU new situations come up, you may wantto read the other sections.Note: In this guide, “children” refersto children of all ages, including teens,H[FHSW ZKHQ WDONLQJ DERXW D VSHFLƬF DJH Other caring adults.This guide is geared toward parents and family, but others who work withFKLOGUHQ PD\ DOVR ƬQG LW XVHIXO 7HDFKHUV FRDFKHV FKLOGFDUH SURYLGHUV DQG RWKHU FDULQJ DGXOWV FDQ RƪHU EHWWHU VXSSRUW WR D FKLOG ZKR KDV ORVW D loved one when they understand more about how children grieve.

Why a parent’s role is important.Your children are experiencing powHUIXO DQG GLƯFXOW IHHOLQJV They wantguidance about what these feelingsmean and how to cope. More thananyone else in their lives, they look toyou for that guidance.Your children are concerned for you, too.They wonder how you are coping. Theymay also worry about your health andsurvival. Your support and reassuranceare most important for them, and canhave more impact than anyone else’s.When a parent is grieving.Talking with your children about aGHDWK LV HVSHFLDOO\ GLƯFXOW ZKHQ \RXoUH dealing with your own grief. Childrenoften ask the same questions adults askthemselves at such times: How couldsomething this unfair happen? How can Igo on if I will never get to see this personagain? Who wants to live in a worldwhere this can occur? What’s goingto become of our family now that thisperson is gone?(VSHFLDOO\ LQ WKHVH GLƯFXOW PRPHQWV your love and support are very important to your children. They learn howto deal with their grief by watchingwhat you do to cope. However, ifthe task of explaining death feelsoverwhelming to you right now, youmay want to have someone else assistyou with the discussion. Think aboutgiving that person this guide to read.More thananyone else intheir lives, theylook to you forguidance.You can still have these conversationswith your children when you are ready.They will need to discuss this more thanonce, and it will matter to them becauseit comes from you.Helping children understand death.Children see and hear many of thesame things adults do. However, theirunderstanding of what these thingsPHDQ PD\ EH TXLWH GLƪHUHQW This isWUXH ZLWK GHDWK GXOWV FDQ KHOS FKLOGUHQ understand death accurately. Thisinvolves more than simply giving themthe facts. It means helping them graspsome important new concepts.Support of this type allows children tounderstand and adjust to the loss fullyas they continue to move forward intheir lives.Four basic conceptsabout death.Everyone, including children, mustunderstand four basic concepts aboutdeath to grieve fully and come to termswith what has happened. Teens, andeven adults, may have a full and rationalunderstanding of death, yet still struggleto accept these basic concepts whenfaced with the death of a loved one. Itis even harder for young children whodo not yet understand the concepts tocope with a loss.There is wide variation in how wellchildren of the same age understanddeath based on what they haveexperienced and the things they havealready learned about it.Don’t assume what your childrenknow based on their age. Instead,ask them to talk about their ideas,WKRXJKWV DQG IHHOLQJV V WKH\ H[SODLQ what they already understand aboutdeath, you’ll be able to see what theystill need to learn. Even toddlers canbegin to understand some of thesebasic concepts.5

Four basic concepts about death.1. Death is irreversible.In cartoons, television shows, and movies, children seecharacters “die” and then come back to life. In real life, thisis not going to happen.Children who don’t fully understand this concept may viewdeath as a kind of temporary separation. They often thinkof people who have died as being far away, perhaps on a trip.Sometimes adults reinforce this belief by talking about theperson who died as having “gone on a long journey.” Childrenmay feel angry when their loved one doesn’t call or return forimportant occasions.If children don’t think of the death as permanent, they havelittle reason to begin to mourn. Mourning is a painful processthat requires people to adjust their ties to the person who hasGLHG Q HVVHQWLDO ƬUVW VWHS LQ WKLV SURFHVV LV XQGHUVWDQGLQJ and, at some level, accepting that the loss is permanent.2. All life functions endcompletely at the timeof death.Very young children view all things as living—their sister, atoy, the mean rock that just “tripped” them. In day-to-dayconversations, adults may add to this confusion by talkingabout the child’s doll being hungry or saying they got homelate because the car “died.”Imaginative play with children is natural and appropriate. But,ZKLOH DGXOWV XQGHUVWDQG WKDW WKHUHoV D GLƪHUHQFH EHWZHHQ pretending a doll is hungry and believing the doll is hungry, thisGLƪHUHQFH PD\ QRW EH FOHDU WR D YHU\ \RXQJ FKLOG Young children are sometimes encouraged to talk to a familymember who has died. They may be told their loved one is“watching over them” from heaven. Sometimes children areasked to draw a picture or write a note to the person who diedWKDW FDQ EH SODFHG LQ WKH FRƯQ These comments can be confusing and even frightening tosome children. If the person who has died could read a note,GRHV LW PHDQ KH RU VKH ZLOO EH DZDUH RI EHLQJ LQ WKH FRƯQ" :LOO the person realize he or she has been buried?Children may know that people can’t move after they’ve died,EXW EHOLHYH WKLV LV EHFDXVH WKH FRƯQ LV WRR VPDOO 7KH\ PD\ know people can’t see after death, but believe this is because itis dark underground. These children may become preoccupiedZLWK WKH SK\VLFDO VXƪHULQJ RI WKH GHFHDVHG When children can correctly identify what living functions are,they can also understand that these functions end completelyat the time of death. For example, only living things can think,be afraid, be hungry, or feel pain. Only living things have abeating heart or need air to breathe.6

3. Everything that is4. There are physicalChildren may believe that they and others close to them willnever die. Parents often reassure children that they will alwaysbe there to take care of them. They tell them not to worryabout dying themselves. This wish to shield children fromGHDWK LV XQGHUVWDQGDEOH %XW ZKHQ D GHDWK GLUHFWO\ DƪHFWV children, this reality can no longer be hidden from them. WhenD SDUHQW RU RWKHU VLJQLƬFDQW SHUVRQ KDV GLHG FKLOGUHQ ZLOO usually fear that others close to them—perhaps everyonethey care about—will also die.Children must understand why their loved one has died. If theydon’t, they’re more likely to come up with explanations thatcause guilt or shame.alive eventually dies.reasons someone dies.The goal is to help children feel they understand what hasKDSSHQHG 2ƪHU D EULHI H[SODQDWLRQ XVLQJ VLPSOH DQG GLUHFW language. Take your cues from your children, and allow them toask for further explanations. Graphic details aren’t necessaryand should be avoided, especially if the death was violent.Children, just like adults, struggle to make sense of a death. Ifthey do not understand that death is an inevitable part of life,WKH\ ZLOO PDNH PLVWDNHV DV WKH\ ƬJXUH RXW ZK\ WKLV SDUWLFXODU death occurred. They may assume it happened because ofsomething bad they did or something they failed to do. Theymay think it happened because of bad thoughts they had. Thisleads to guilt. They may assume the person who died did orthought bad things, or didn’t do something he or she shouldhave done. This leads to shame.7KHVH UHDFWLRQV PDNH LW GLƯFXOW IRU FKLOGUHQ WR DGMXVW WR WKH loss. Many children don’t want to talk about the death becauseit will expose these terrible feelings of guilt and shame.When you talk to your children about this concept, let themknow you are well, and that you are doing everything you canto stay healthy. Explain that you hope and expect to live a veryORQJ WLPH XQWLO \RXU FKLOGUHQ DUH DGXOWV 7KLV LV GLƪHUHQW IURP telling children that you or they will never die.7

Explaining death to children.Talkingwith yourchildrenprovides achance forthem to showyou theirfeelings.6RPHWLPHV FKLOGUHQ GRQoW UHDFW WR news of a death the way their parentsand other adults expect them to. Thereare many ways explanations aboutdeath can confuse children.Explanations and terms may not beclear. GXOWV RIWHQ FKRRVH ZRUGV WKH\ feel are gentler or less frightening forchildren. They might avoid using thewords “dead” or “died,” which seemharsh at such an emotional time. But,with these less direct terms, childrenmay not understand what the adultis saying. For example, if an adult tellschildren that their loved one is now in astate of “eternal sleep,” the children maybecome afraid to go to sleep.What to do.Speak gently, but frankly and directlyto children. Use the words “dead” and“died.”Children may only understand part ofthe explanation. Even when adults giveclear, direct explanations, children maynot fully understand. For example, somechildren who have been told that thebody was placed in a casket worry aboutwhere the head has been placed.What to do.Check back with your children to seewhat they understand. You might say,“Let me see if I’ve explained this well.Please tell me what you understand hashappened.”

Religious concepts may be confusing.It is appropriate to share the family’sreligious beliefs with children when adeath has occurred, but remember thatreligious beliefs may be abstract andGLƯFXOW IRU FKLOGUHQ WR XQGHUVWDQG What to do.Present the facts about what happensto the physical body, as well as thereligious beliefs held by the family. ForH[DPSOH FKLOGUHQ PLJKW ƬUVW EH WROG that the person has died. His or her bodyno longer thinks, feels, or sees. Theperson’s entire body has been placed ina casket and buried. In some faiths, theadult might then explain that there is aspecial part of the person that cannotbe seen or touched, which some peoplecall the spirit or soul, and that this partcontinues on in a place we cannot see orvisit, which is called heaven.How children respond to death.&KLOGUHQoV UHDFWLRQV WR D GHDWK PD\ communicate their thoughts, feelings,and fears. Sometimes these reactionsare confusing to adults. But, whenadults understand what children arecommunicating, everything makesmore sense.Here are some common reactionschildren may have.Children may become upset by thesediscussions. Keep in mind that it isn’tthe conversation causing distress, butthe very painful loss felt from the deathof a loved one. Talking with your childrenprovides a chance for them to show youtheir feelings. When you understand theirfeelings, it’s easier to help them cope withthe experience.What to do.Pause the conversation if that seemsbest. Provide support and comfort. Planto continue the talk another time soon.Children may be reluctant to talk abouta recent death. Often this happensbecause they see that the adults aroundthem are uncomfortable talking aboutthe death. Children may withhold theirown comments or questions to avoidupsetting family members. They maybelieve it’s wrong to talk about suchthings. Older children and teens mayturn to peers to discuss the death. Theymay tell adults close to them that theydon’t want or need to talk about it.What to do.Avoid forcing the issue or getting intopower struggles about it.Continue to invite your children to talkon several occasions over time.Acknowledge that these conversationsFDQ EH GLƯFXOW Let your children know\RX ƬQG WDONLQJ KHOSIXO /HW \RXU FKLOGUHQ NQRZ LWoV 2. WR VKRZ their feelings. Otherwise, they might tryto hide their feelings and deal with themwithout your support. Let them knowit’s OK to cry. Crying may help them feelbetter.Help older children and teens identifyother adults in their lives with whomthey can talk. Look for people who areQRW DV GLUHFWO\ DƪHFWHG E\ WKH GHDWK such as a teacher, chaplain, schoolcounselor, mental health professional,or a pediatrician or other health careprovider.Show them your own feelings.Demonstrate how you are coping. Letyour children see you crying, talkingwith friends, seeking spiritual comfort,or remembering good things about theperson who has died.Maintain an emotional and physicalpresence with your children. Hug them.7DON DERXW \RXU IHHOLQJV VN DERXW theirs. Even older children and teensneed your support and assistance asthey cope with the loss.9

Children mayuse play orcreative activities suchas drawingor writing toexpress theirgrief.Children may express their feelingsin ways other than talking. Childrenmay use play or creative activities suchas drawing or writing to express theirgrief. Often, they come to a betterunderstanding of grief through play andcreativity. These expressions can giveyou some important clues about whatchildren are thinking, but be careful notto jump to conclusions. For example,very happy drawings after a traumaticdeath might give adults the idea that aFKLOG LV QRW DƪHFWHG E\ WKH GHDWK ZKHQ in fact, this is more likely a sign that thechild is not yet ready to deal with thegrieving process.What to do.2ƪHU \RXU FKLOGUHQ RSSRUWXQLWLHV WR play, write, draw, paint, dance, make upsongs, or do other creative activities.Ask them to tell you about theirartwork. For example, you might say,“Tell me what’s happening in this pictureyou drew.” If there are people in thedrawing, ask who they are, what they’refeeling, whether anyone is missing fromthe picture, and so on.,I \RXoUH ZRUULHG WKDW \RXU FKLOGUHQoV play or creative work shows they arehaving trouble coping with the death,seek outside help. (See the section“Getting help” on page 18.)10Children often feel guilty after a deathhas occurred. Young children have alimited understanding of why thingshappen as they do. They often use aprocess called magical thinking. Thismeans they believe their own thoughts,wishes, and actions can make thingsKDSSHQ LQ WKH JUHDWHU ZRUOG GXOWV PD\ reinforce this misconception when theysuggest that children make a wish forsomething they want to happen.Magical thinking is useful at times. Beingable to wish for things to be better intheir lives and in the world can helpyoung children feel stronger and morein control. But there’s also a downside,because when something bad happens,such as the death of a loved one, childrenmay believe it happened because ofsomething they said, did, thought,or wished.Older children and teens also usuallywonder if there is something they couldhave done, or should have done, toprevent the death. For example, theparent wouldn’t have had a heart attackif the child hadn’t misbehaved andcaused stress in the family. The car crashwouldn’t have happened if the childdidn’t need to be picked up after school.The cancer wouldn’t have progressedif the child had just made sure the lovedone had seen a doctor.

When guilt is more likely.Children are most likely to feel guilty when there have been challengesin the relationship with the person who died, or in the circumstancesof the death. Here are some examples: The child was angry with the person just before the person died. The death occurred after a long illness, and, at times, the child mayKDYH ZLVKHG WKH SHUVRQ ZRXOG GLH WR HQG HYHU\RQHoV VXƪHULQJ Some action of the child seems related to the death. For example, ateen got into a heated argument with his mother shortly before shedied in a car crash.

Children andteens usuallywonder if thereis somethingthey could havedone, or shouldhave done, toprevent thedeath.Children may feel guilty for survivingthe death of a sibling. They may alsofeel guilty if they are having fun or notfeeling very sad after a family memberhas died.Set limits on inappropriate behaviors.It’s not OK for children to hit or hurtothers, or for teens to put themselves orothers at risk in dangerous situations.When talking with children about thedeath of someone close, it’s appropriateto assume that some sense of guilt maybe present. This will usually be the caseeven if there is no logical reason for thechildren to feel responsible.Children may appear to think onlyabout themselves when confrontedwith a death. W WKH EHVW RI WLPHV children are usually most concerned withWKH WKLQJV WKDW DƪHFW WKHP SHUVRQDOO\ W WLPHV RI VWUHVV VXFK DV DIWHU WKH death of someone they care about, theymay appear even more self-centered.What to do.Explain that when painful or “bad”things happen, people often wonder if itwas because they did something bad.Reassure your children that they arenot responsible for the death, even ifthey haven’t asked about this directly.Children often express anger aboutthe death. They may focus on someonethey feel is responsible. They may feelangry at God. They may feel angry at theperson who died for leaving them. Familymembers sometimes become the focusof this anger, because they are near andare “safe” targets.Encourage yourchildren to talkwith someonethey trust.2OGHU FKLOGUHQ DQG WHHQV PD\ HQJDJH in risky behaviors. They may driveUHFNOHVVO\ JHW LQWR ƬJKWV GULQN DOFRKRO smoke cigarettes, or use drugs. Theymay become involved in sexual activityor delinquency. They may start to haveSUREOHPV DW VFKRRO RU FRQƮLFWV ZLWK friends.What to do.Allow children to express their anger. YRLG EHLQJ FULWLFDO DERXW WKHVH IHHOLQJV Recognize that anger is a normal andnatural response.Help children identify appropriateways to express their anger. Encouragethem to talk about it with someone theytrust. Suggest that they do somethingphysical, such as running, sports,dancing, or yard work, or express theanger through creative activities, suchas writing or art.12 W D WLPH RI WUDJHG\ ZH RIWHQ H[SHFW children to rise to the occasion and actmore “grown-up.” It’s true that childrenZKR KDYH FRSHG ZLWK GLƯFXOW HYHQWV often emerge with greater maturity. But,in the moment itself, most children, andeven adults, may act less maturely.Under stress, children may behave asthey did at a younger age. For example,children who have recently masteredtoilet training may start to have accidents.Children who have been acting withgreater independence may become clingyRU KDYH GLƯFXOW\ ZLWK VHSDUDWLRQ Children and teens can also act lessmature socially. They may becomedemanding, refuse to share, or pickƬJKWV ZLWK IDPLO\ PHPEHUV 7KH\ PD\ respond to the death in ways that seemFROG RU VHOƬVK p'RHV WKLV PHDQ , FDQoW have my birthday party this weekend?”p P , VWLOO JRLQJ WR EH DEOH WR JR WR WKH college I want?”Expect your children to think more aboutthemselves when they are grieving, atOHDVW DW ƬUVW 2QFH WKH\ IHHO WKHLU QHHGV are being met, they will be able to thinkmore about the needs of others.What to do.Continue to show caring and concernfor your children.Remember that your children are stillgrieving, even when they behave inthese ways.Set appropriate limits on behaviors, butresist the temptation to accuse childrenRI EHLQJ VHOƬVK RU XQFDULQJ

Attending funerals and memorials.When a close friend or relativedies, FKLOGUHQ VKRXOG EH RƪHUHG WKH opportunity to attend the funeral ormemorial service whenever possible.Family members sometimes worry that afuneral will be frightening for the children,or that they will not understand whatis happening.Let your children decide whether ornot to attend. You can let them knowthat you’d like them to be there, butdon’t ask them to participate in anyULWXDO RU DFWLYLW\ WKH\ ƬQG IULJKWHQLQJ RU unpleasant. Let them know that theycan leave at any point or just take a breakfor a few minutes.But when children are not allowed toattend services, they often createfantasies far more frightening than whatactually occurs. They are likely to wonder,“What can they possibly be doing with mymother that is so awful I’m not allowedto see?” They may also feel hurt if theyare not included in this important familyevent. They lose an opportunity to feelthe comfort of spiritual and communitysupport provided through services.Find an adult to be with each child.Especially for young children andSUHWHHQV ƬQG DQ DGXOW ZKR FDQ VWD\ ZLWK each child throughout the service. Thisperson can answer questions, providecomfort, and give the child attention.Ideally, this will be someone the childknows and likes, such as a babysitter orQHLJKERU ZKR LVQoW DV GLUHFWO\ DƪHFWHG by the death. This allows the adult tofocus on the child’s needs, includingleaving the service if the child wishes.You can take steps before, during, andafter the service to help your childrenEHQHƬW What to do.Explain what will happen. In simpleterms, let your children know what toexpect. Where will the service takeplace? Who will be there? Will therebe music?Describe what people will do at theservice. Will guests be crying? Willpeople share stories? Will people bevery serious, or will there be laughter?7DON DERXW WKH VSHFLƬF IHDWXUHV RI WKH service. Will there be a casket? Will it bean open casket? Will there be a funeralprocession or a graveside service?Answer questions. Encourage yourchildren to ask any questions before theservice. Check in with them more thanonce on this.Children shouldbe offered theopportunityto attend thefuneral ormemorialservice.Allow options. Younger children mightwant to play quietly in the back of thesanctuary, which can still give them asense of having participated in the ritualin a direct way. Older children or teensmay want to invite a close friend to sitwith them in the family section.2ƪHU D UROH LQ WKH VHUYLFH It may behelpful for children to have a simple task,such as handing out memorial cards orKHOSLQJ WR FKRRVH ƮRZHUV RU D IDYRULWH song for the service. It’s important tosuggest something that will comfort andnot overwhelm the children.Check in afterward. Be sure to speak to\RXU FKLOGUHQ DIWHU WKH VHUYLFH DQG RƪHU them your comfort and love. Over thenext few days, ask what they thought ofthe service. Do they have any feelingsthey want to share or questions to ask? UH WKHPHV IURP WKH VHUYLFH VKRZLQJ XS in their play or drawings?13

Helping children cope over time.Grief is not a quick process. Peoplewho’ve lost a family member generallyfeel that loss throughout their lives. Tocontinue giving your children support,it’s important to understand how theymay cope with their grief over time.1R FKLOG LV WRR \RXQJ WR EH DƪHFWHG by the death of someone close. Eveninfants respond to a death. They missthe familiar presence of a parent whohas died. They sense powerful emotionsaround them, and notice changes infeeding and caregiving routines.Young children can grieve deeply, eventhough they may not appear to be doingso. They don’t usually sustain strongemotions the way adults do. They mayYLVLW WKHLU FRQFHUQV EULHƮ\ DQG WKHQ WXUQ to play or schoolwork. This helps themavoid being overwhelmed, but doesn’tnecessarily mean their concerns havebeen addressed.Older children and teens may try tofocus their attention on schoolwork,sports, or hobbies. They may assumemore responsibilities at home by helpingtheir parents or other children in thefamily. Encourage your children tocontinue their friendships with peers andthe activities they enjoyed prior to thedeath. Even after the death of a familymember, it’s important for children tokeep being children.Here are some ways adult familymembers and friends can supportchildren over time.Help children preserve—and create—memories. Children sometimes worrythat they will forget the person who died,especially if they were quite young at thetime of the death. The entire family cankeep the person’s memory alive throughstories, pictures, and continued mentionof the person in everyday conversation.No child istoo young tobe affected bythe death ofsomeone close.Even infantsrespond toa death.Parents can model ways to talk aboutthe person who has died and makehis or her memory a part of holidaysand other special occasions. Findingways to recognize and remember whatwas valuable in the relationship withthe person who has died is part of thehealing process.Children often like to have physicalreminders of the person who has died.Some children want to carry a picture orobject that reminds them of their familymember or keep it in a special place inthe home. They may keep clothing ora pillow in their room that still has theperson’s scent on it.Parents have these feelings, too.Parents have many of these same feelings—guilt, anger, confusion,feeling needy or less comfortable doing things on their own. They oftenwant to keep their children nearby at these times, so they can be suretheir children are safe. They may look to their children to help themmake decisions or provide them with support.These are natural and appropriate feelings. But it’s also important forparents to step back when their children want or need to be more independent. This may happen soon after the death, or several weeks later.Parents also should be careful about giving children responsibilities thatZRXOG EH PRUH DSSURSULDWH IRU DGXOWV RU DERXW DVNLQJ FKLOGUHQ WR ƬOO WKH roles of the adult who has died.15

Childrensometimesworry thatthey willforget thepersonwho has died.Anticipate grief triggers. Memoriesand feelings of grief can be triggered byanniversaries or other important events.7KH ƬUVW KROLGD\ DIWHU WKH GHDWK WKH ƬUVW ELUWKGD\ WKH ƬUVW GD\ RI VFKRRO D IDWKHU daughter dance—any of these mightbring up sudden and powerful feelings ofsadness.Everyday events can have an impactas well—a favorite song may come onthe radio, a favorite dish might be onthe menu at a restaurant, a child mightcome across an old card from the familymember who has died. These griefWULJJHUV RIWHQ FDWFK SHRSOH Rƪ JXDUG They can be troubling to children whoare trying hard not to think about theperson who has died.Help your children understand thatthese experiences are natural. They willhappen less frequently over time, butmay continue to be powerful.7DON WR \RXU FKLOGUHQoV WHDFKHUV IWH

Sometimes adults reinforce this belief by talking about the person who died as having "gone on a long journey." Children may feel angry when their loved one doesn't call or return for important occasions. If children don't think of the death as permanent, they have little reason to begin to mourn. Mourning is a painful process