Transcription

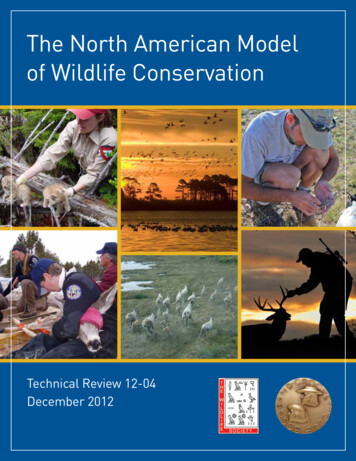

The North American Modelof Wildlife ConservationTechnical Review 12-04December 20121

The North American Modelof Wildlife ConservationThe Wildlife Society and The Boone and Crockett ClubTechnical Review 12-04 - December 2012CitationOrgan, J.F., V. Geist, S.P. Mahoney, S. Williams, P.R. Krausman, G.R. Batcheller, T.A. Decker, R. Carmichael,P. Nanjappa, R. Regan, R.A. Medellin, R. Cantu, R.E. McCabe, S. Craven, G.M. Vecellio, and D.J. Decker. 2012.The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation. The Wildlife Society Technical Review 12-04. The WildlifeSociety, Bethesda, Maryland, USA.Series Edited byTheodore A. BookhoutCopy Edit and DesignTerra Rentz (AWB ), Managing Editor, The Wildlife SocietyLisa Moore, Associate Editor, The Wildlife SocietyMaja Smith, Graphic Designer, MajaDesign, Inc.Cover ImagesFront cover, clockwise from upper left: 1) Canada lynx (Lynx canadensis) kittens removed from den formarking and data collection as part of a long-term research study. Credit: John F. Organ; 2) A mixed flock ofducks and geese fly from a wetland area. Credit: Steve Hillebrand/USFWS; 3) A researcher attaches a radiotransmitter to a short-horned lizard (Phrynosoma hernandesi) in Colorado’s Pawnee National Grassland.Credit: Laura Martin; 4) Rifle hunter Ron Jolly admires a mature white-tailed buck harvested by his wife onthe family’s farm in Alabama. Credit: Tes Randle Jolly; 5) Caribou running along a northern peninsula ofNewfoundland are part of a herd compositional survey. Credit: John F. Organ; 6) Wildlife veterinarian LisaWolfe assesses a captive mule deer during studies of density dependence in Colorado. Credit: Ken Logan/Colorado Division of Wildlife.TWS would like to thank The Boone and Crockett Program at the University of Montana for providing financialsupport for publication. This report is copyrighted by TWS, but individuals are granted permission to makesingle copies for noncommercial purposes. To view or download a PDF of this report, or to order hard copies,go to: wildlife.org/publications/technical-reviews.ISBN: 978-0-9830402-3-1The North American Model of Wildlife Conservationi

iiThe North American Model of Wildlife Conservation

Technical Review Committee on The NorthAmerican Model of Wildlife ConservationJohn F. Organ (Chair, CWB )*, **Gordon R. Batcheller (CWB )Ruben Cantu (CWB )U.S. Fish and Wildlife ServiceNew York State Div. of Fish, Wildlife &Texas Parks and Wildlife Department300 Westgate Center DriveMarine Resources151 Las Lomas Ct.Hadley, MA 01035 USA625 BroadwaySan Angelo, TX 76901 USAAlbany, NY 12233 USAValerius Geist*Richard E. McCabe*Faculty of EnvironmentalThomas A. Decker (CWB )Wildlife Management InstituteDesign (Emeritus)Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department1424 NW Carlson Road2500 University Dr. NW103 South Main StreetTopeka, Kansas 66615 USAUniversity of CalgaryWaterbury, VT 05671 USACalgary, Alberta, T2N 1N4 CAScott CravenRobert CarmichaelDepartment of Wildlife EcologyShane P. Mahoney*Delta Waterfowl FoundationRoom 226 Russell LaboratoriesSustainable Development andSite 1, Box 87University of WisconsinStrategic Science BranchKeewatin, Ontario POX 1C0 CA1630 Linden DriveDepartment of EnvironmentMadison WI 53706 USAand ConservationPriya NanjappaP.O. Box 8700Association of Fish andGary M. VecellioSt. John’s, NL A1B 4J6 CAWildlife AgenciesIdaho Fish and Game444 North Capitol Street, NW,4279 Commerce CircleSteven Williams*Suite 725Idaho Falls, ID 83401 USAWildlife Management InstituteWashington, DC 20001 USADaniel J. Decker (CWB )1440 Upper Bermudian RoadRonald Regan (CWB )*Human Dimensions Research UnitAssociation of Fish and206 Bruckner HallPaul R. Krausman (CWB )*Wildlife AgenciesDepartment of Natural ResourcesBoone and Crockett Professor of444 North Capitol Street, NW, Suite 725Cornell UniversityWildlife ConservationWashington, DC 20001 USAIthaca, NY 14853 USACollege of Forestry and ConservationRodrigo A. Medellin32 Campus DriveInstituto de Ecología, UNAM*Professional members of the Booneand Crockett ClubUniversity of MontanaAp. Postal 70-275Missoula, Montana 59812 USA04510 Ciudad Universitaria, D. F.Gardners, PA 17324 USAWildlife Biology ProgramMEXICO** The findings and conclusions in thisarticle are those of the author and donot necessarily represent the views ofthe U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.The North American Model of Wildlife Conservationiii

ivThe North American Model of Wildlife Conservation

Table of ContentsForeword viAcknowledgements viiExecutive SummaryviiiIntroduction1Historical Overview 3Canada and the United States6Implementation in Canada and the United StatesCanada 6United States 8Review of Model Components 11111. Wildlife Resources Are a Public Trust2. Markets for Game Are Eliminated 143. Allocation of Wildlife Is by Law 16184. Wildlife Can Be Killed Only for a Legitimate Purpose195. Wildlife Is Considered an International Resource6. Science Is the Proper Tool to Discharge Wildlife Policy207. Democracy of Hunting Is Standard 23Sustaining and Building Upon the Model 24Funding 25Wildlife Markets 25Firearms Rights and Privileges 25Habitat Considerations 26Taxa Inclusivity 28Governance 28The Future of the Model 29Summary and Recommendations 30Literature Cited 31Appendix: Status of Wildlife Management in Mexico35The North American Model of Wildlife Conservationv

ForewordPresidents of The Wildlife Society (TWS)occasionally appoint ad hoc committees tostudy and report on selected conservation issues.The reports ordinarily appear as technical reviewsor position statements. Technical reviews presenttechnical information and the views of the appointedcommittee members, but not necessarily the views oftheir employers.This technical review focuses on the set ofprinciples known as the North American Modelof Wildlife Conservation and was developed inpartnership with the Boone and Crockett Club. Thereview is copyrighted by TWS, but individuals aregranted permission to make single copies for noncommercial purposes. All technical reviews andposition statements are available in digital format atwww.wildlife.org/. Hard copies may be requested orpurchased from:The Wildlife Society5410 Grosvenor Lane, Suite 200Bethesda, MD 20814Phone: (301) 897-9770Fax: (301) 530-2471TWS@wildlife.orgwww.wildlife.orgWeighing a fawn during studies of density dependence in Colorado.Courtesy of the Colorado Division of Wildlife.viThe North American Model of Wildlife Conservation

AcknowledgmentsCommissioners representing Canada, Mexico, and the United States at the 1909 North American Conservation Congress. PresidentTheodore Roosevelt sits at center. Credit: Forest History Society.We acknowledge the support of TWSPresidents in office during preparation ofthis report, including President Paul R. Krausmanand Past Presidents Tom Ryder, Bruce Leopold,Tom Franklin, and Dan Svedarsky. We are grateful toTheodore Bookhout for his thorough editing. Membersof The Wildlife Society Council John McDonald, RickBaydack, Darren Miller, and Ashley Gramza (StudentLiaison) provided comments and support. The WildlifeSociety editors Laura Bies, Terra Rentz, and ChristineCarmichael provided encouragement, invaluablesuggestions, and edits. This review was approved fordevelopment in March 2007 by then-President JohnF. Organ and approved for publication in October 2012by then-President Paul R. Krausman. We would liketo recognize the financial support provided by both theBoone and Crockett Club and The Boone and CrockettProgram at the University of Montana for publication,printing, and distribution.The North American Model of Wildlife Conservationvii

Executive SummaryBison (Bison bison ) in Yellowstone National Park. Credit: Jim Peaco, NPS.The North American Model of Wildlife Conservationwhether we are prepared to address challenges thatis a set of principles that, collectively applied,lay ahead. Simply adding to, deleting, or modifying thehas led to the form, function, and successes of wildlifeexisting principles will not in itself advance conservation.conservation and management in the United States andUnderstanding the evidentiary basis for the principlesCanada. This technical review documents the history andis essential to preventing their erosion, and necessarydevelopment of these principles, and evaluates currentfor the conceptual thinking required to anticipate futureand potential future challenges to their application.challenges. A brief summary of some of the challengesDescribing the Model as North American is done inand concerns follows:a conceptual, not a geographical, context. Wildlifeconservation and management in Mexico developed1. Wildlife resources are a public trust. Challengesat a different time and under different circumstancesinclude (1) inappropriate claims of ownership of wildlife;than in the U.S. and Canada. The latter two were hand(2) unregulated commercial sale of live wildlife; (3)in hand. The history, development, and status of wildlifeprohibitions or unreasonable restrictions on access toconservation and management in Mexico are outlinedand use of wildlife; and (4) a value system endorsing anseparately as part of this review.animal-rights doctrine and consequently antithetical to thepremise of public ownership of wildlife.It is not the intent or purpose of this review to revise,viiimodify, or otherwise alter what has heretofore been2. Markets for game are eliminated. Commercial tradeput forward as the Model. Indeed, the Model itself isexists for reptiles, amphibians, and fish. In addition, somenot a monolith carved in stone; it is a means for us togame species are actively traded. A robust market forunderstand, evaluate, and celebrate how conservationaccess to wildlife occurring across the country exists in thehas been achieved in the U.S. and Canada, and to assessform of leases, reserved permits, and shooting preserves.The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation

3. Allocation of wildlife is by law. Application andenforcement of laws to all taxa are inconsistent. Althoughstate authority over the allocation of the take of residentgame species is well defined, county, local, or housingdevelopment ordinances may effectively supersede stateauthority. Decisions on land use, even on public lands,indirectly impact allocation of wildlife due to land usechanges associated with land development.4. Wildlife can be killed only for a legitimate purpose.Take of certain species of mammals, birds, reptiles, andamphibians does not correspond to traditionally acceptednotions of legitimate use.5. Wildlife is considered an international resource.Many positive agreements and cooperative efforts havebeen established among the U.S., Canada, Mexico, andother nations for conserving wildlife. Many more speciesneed consideration. Restrictive permitting procedures,although designed to protect wildlife resources, inhibittrans-border collaborations. Construction of a wall toprevent illegal immigration from Mexico to the U.S. willhave negative effects on trans-border wildlife movementsand interactions.6. Science is the proper tool to discharge wildlifepolicy. Wildlife management appears to be increasinglypoliticized. The rapid turnover rate of state agencydirectors, the makeup of boards and commissions,the organizational structure of some agencies, andexamples of politics meddling in science have challengedthe science foundation.Trapping raccoons (Procyon lotor) in Missouri, biologist Dave Hamilton(now deceased) helped assess traps for the BMP program. Courtesy ofThomas Decker.7. Democracy of hunting is standard. Reduction in, andaccess to, huntable lands compromise the principle ofegalitarianism in hunting opportunity. Restrictive firearmslegislation can act as a barrier hindering participation.To help address these challenges, this review presentsseveral recommendations. These are offered asactions deemed necessary to ensure relevancy of theModel in the future.The North American Model of Wildlife Conservationix

IntroductionInternational trade in wildlife products came under greater scrutiny with the ratification of CITES by the U.S. in 1975. Credit: John andKaren Hollingsworth, USFWS.Wildlife conservation varies worldwide inits form, function, and underlyingprinciples. In recent years, efforts have been directedto describe the key attributes that collectively makewildlife conservation in North America unique.Although efforts to articulate wildlife conservation inNorth America have come of late, awareness amongpractitioners in the U.S and Canada that their wildlifeconservation programs differed from others aroundthe world has existed for decades. Describing theseattributes or principles can serve many purposes:foster celebration of the profession’s maturation1The North American Model of Wildlife Conservationand accomplishments; serve as an educational tool;and identify gaps, shortcomings, or areas in needof expansion to address contemporary or futurechallenges. The intent of this technical review is tocontribute to all of these purposes.A model is a description of a system that accountsfor its key properties (Soukhanov 1988). The conceptthat wildlife conservation in North America could bedescribed as a model was first articulated by Geist(Geist 1995, Geist et al. 2001), who coined the term“North American Model of Wildlife Conservation”

(Model). Geist’s direct knowledge of and familiaritywith wildlife conservation programs of other nationsprovided a perspective on Canada and the U.S. Theconcept was further developed by Mahoney (2004).Today, the Model has become the basis for policiesdeveloped by the Association of Fish and WildlifeAgencies (Prukop and Regan 2005) and The WildlifeSociety (The Wildlife Society 2007). It was the keyunderpinning for U.S. Executive Order 13443 that ledto the White House Conference on North AmericanWildlife Policy (Mahoney et al. 2008, SportingConservation Council 2008a) and fostered theRecreational Hunting and Wildlife Conservation Plan(Sporting Conservation Council 2008b).Seven components or principles describe the keyproperties of the Model (Geist et al. 2001, Organ etal. 2010):1. Wildlife resources are a public trust.2. Markets for game are eliminated.3. Allocation of wildlife is by law.development, current status, threats and challenges,and differences and commonalities in applicationwithin Canada and the U.S. This information is thenused to further define the Model.Wildlife conservation in Canada and the U.S.developed under unique temporal and socialcircumstances, and the resulting Model reflectsthat. Had it formed in another time and underother circumstances it would likely be different.Use of the term “North American” to describethe Model is conceptual rather than geographic.Mexico’s wildlife conservation movement began itsdevelopment and evolution at a different time andunder different circumstances. It is unrealistic toexpect that movement to mirror those of the U.S.and Canada. A description of the evolution andcurrent status of wildlife conservation in Mexico isprovided in Appendix I. Further work is warrantedto compare how different temporal and socialcircumstances have led to different conservationapproaches, identify what can be learned from thosecomparisons, and what is needed to advance wildlifeconservation within Canada, Mexico, and the U.S.4. Wildlife can be killed only for a legitimate purpose.5. Wildlife is considered an international resource.6. Science is the proper tool to dischargewildlife policy.7. Democracy of hunting is standard.These seven components formed the foundation forwildlife conservation in Canada and the U.S., butquestions have arisen as to the validity of certaincomponents in contemporary times and whetherscrutiny of conservation programs would deemmany of these operationally intact. Additionally,the question as to whether the Model is inclusiveof all wildlife conservation interests or exclusivelynarrow in its application has been posed (Beuchlerand Servheen 2008). To address these questions wedescribe and analyze each component in terms of itsPeregrine falcons were protected in the United Statesunder the 1973 Endangered Species Act. Recovery effortssucceeded in their restoration and removal from the federalEndangered Species List. Credit: Craig Koppie, USFWS.The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation2

Historical OverviewThe exploration of North America by theFrench and English was fundamentallymotivated by the wealth of the continent’s renewablenatural resources and an unfettered opportunityby individuals to exploit them (Cowan 1995). Today,wildlife conservation in Canada and the U.S. reflectsthis historic citizen access to the land and its naturalresources. Indeed, the sense that these resourcesbelong to the citizenry drives the democraticengagement in the conservation process and is theraison d’etre of North America’s unique approach(Krausman, P., Gold, silver, and souls, unpublishedpresentation at The Wildlife Society AnnualConference, 22 September 2009, Monterey, CA, USA).Resource exploitation fueled the expansion ofpeople across the continent and led to eventualdisappearance of the frontier (Turner 1935). Aselsewhere, the Industrial Revolution broughtchanges to North American society that alteredthe land and its wildlife. In 1820, 5 percent ofAmericans lived in cities; by 1860 20 percent wereurban dwellers, a 4-fold increase that marks thegreatest demographic shift ever to have occurred inAmerica (Riess 1995). Markets for wildlife arose tofeed these urban masses and festoon a new classof wealthy elites. Market hunters plied their tradefirst along coastal waters and interior forests. Then,with the advent of railways and refrigeration, theyexploited bison (Bison bison), elk (Cervus elaphus),and other big game of western North America fortransport back to cities in eastern North America.The market hunter left many once-abundant speciesteetering on the brink of extinction. Ironically, thesheer scale of this unmitigated exploitation was tohave some influence on engendering a remarkablenew phenomenon: protectionism and conservation(Mahoney 2007).3The North American Model of Wildlife ConservationThe increasing urban population, meanwhile, foundthemselves with something their countrymenon the farms did not have: leisure time. Huntingfor the rigors and challenges of the chase underconditions of fair play became a favored pastimeof many, particularly among those of means. Thisdeveloped in situ, but there can be no doubt thatEuropean aristocratic perspectives toward huntingexerted some influence on these emerging trends(Herbert 1849). Threlfall (1995) noted that Europeancommoners never ceased desiring to participatein the hunt, despite the best and brutal efforts ofnobility to discourage them. In the U.S., conflictssoon arose between market hunters who profitedon dead wildlife and this new breed of hunterswho placed value on live wildlife and their sportingpursuit of it. These sport hunters organized anddeveloped the first refuges for wildlife (Carroll’sIsland Club 1832, Gunpowder River in Maryland;Trefethen 1975) and laws to protect game (e.g., NewYork Sportsmen’s Club 1844; Trefethen 1975).Representative of these sport hunters was the highlyinfluential George Bird Grinnell, a Yale-educatednaturalist who accompanied George ArmstrongCuster on his Black Hills expedition and whoacquired the sporting journal Forest and Stream in1879. Over the next 3 decades, Grinnell would turnForest and Stream into a call for wildlife conservation(Reiger 1975). In 1885, he reviewed a book writtenby a fellow New Yorker about his hunting exploitsin the Dakotas (Grinnell 1885). Grinnell’s reviewwas laudatory, but he criticized the author for someinaccuracies. The author, Theodore Roosevelt, wentto meet Grinnell and the two realized that muchhad changed during the 10 years that divided theirrespective times in the West, and that big gameanimals had declined drastically. Their discussioninspired them to form the Boone and Crockett Club

in 1887, an organization whose purpose wouldinclude to “take charge of all matters pertaining tothe enactment and carrying out of game and fishlaws” (Reiger 1975:234).Roosevelt and Grinnell were also nation builderswho felt America was a strong nation because, likeCanada, its people had carved the country out of awilderness frontier with self-reliance and pioneerskills. This harkened back to ideals regarding theimpact of the frontier on shaping what it is to bean American; ideals articulated in the late 19thcentury by Turner (1935). Turner described theromantic notion of primitivism, for which the bestantidote to the ills of an overly refined and civilizedmodern world was a return to a simpler, moreprimitive life (Cronon 1995). With no frontier anda growing urban populace, Roosevelt and Grinnellfeared America would lose this edge. They believedAmericans could cultivate pioneer skills and asense of fair play through sport hunting, and therebymaintain the character of the nation (Cutright1985, Miller 1992, Brands 1997). The Boone andCrockett Club had many influential members, andthis was used to great effect in support of theseideals. Two of North America’s most important andenduring conservation legacies were written byclub members: the Lacey Act (Congressman JohnLacey from Iowa, 1900) and the Migratory Bird TreatyConvention (Canadian Charles Gordon Hewitt, 1916).And, of course, President Theodore Roosevelt didmore to conserve wildlife than any single individualin U.S. history through the institutionalizationand popularization of conservation and by greatlyexpanding federal protected lands (Brinkley 2009).Canada did not embrace the policies and practices ofwildlife ownership and management as accepted inGreat Britain, foremost among these being the tie ofwildlife and hunting to landownership, and the saleof wildlife as a commodity in the marketplace. Evenmore remarkable is the fact that some of Canada’snegotiators and movers who were instrumental increating this new system of wildlife conservationwere Englishmen, immigrants to Canada.It appears that at the turn of the century, when bothnations had become cognizant of wildlife’s plight andgrappled for solutions, like-minded elites arose onboth sides of the border who knew and befriendedeach other, learned from each other’s successes andEarly settlers killed wolves and other predators with abandon, blaming them for declines in game populations. Courtesy ofThomas J. Ryder.The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation4

Some 40,000 bison pelts in Dodge City, Kansas await shipment to the East Coast in 1878—evidence of the rampant exploitation of thespecies. The end of market hunting and continuing conservation efforts have given bison a new foothold across parts of their historicrange, including Yellowstone National Park. Courtesy of National Archives.failures, and acted on them with insight and resolve.The Canadian effort revolved around the Commissionon Conservation, which was constituted underThe Conservation Act of 1909. The Commissionwas chaired until 1918 by Sir Clifford Sifton andconsisted of 18 members and 12 ex-officio members(Geist 2000).By the early 20th century, considerable wildlifeconservation infrastructure was in place, but bythe 1920s it was clear that the system’s emphasison restrictive game laws was insufficient in itselfto stem wildlife’s decline. Aldo Leopold, A. WillisRobertson, and other conservationists publishedan American Game Policy in 1930 (Leopold 1930)that proposed a program of restoration to augmentconservation’s legal framework. They called fora wildlife management profession with trainedbiologists, stable, equitable funding to enable theirwork and university programs to train them. Within5The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation10 years much of what the policy called for hadbeen realized, with the first game managementcurricula established at the University of Michiganand the University of Wisconsin and the creation ofCooperative Wildlife Research Units, the formationof The Wildlife Society, and the passage of thePittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration andDuck Stamp Acts. These accomplishments wereall initially founded in the U.S. but many wereendorsed and mirrored by various Canadianpolicies and programs.Subsequent decades brought expanded legislation(e.g., U.S. Endangered Species Act, CanadianSpecies at Risk Act) and programs (e.g., MigratoryBird Joint Ventures, Teaming With Wildlife), buttheir principles had been set firmly in place. Theseprinciples arose amidst social and environmentalcircumstances that were unique to the world in theirtemporal juxtaposition.

Implementation in Canadaand the United StatesCanadaGovernance.— Responsibility for wildlife conservationis assigned by the Canadian Constitution and isshared between the provinces or territories and thefederal government. Variations on almost all of thefollowing occur in many parts of Canada, but thegeneral situation is described below.Provincial and territorial authority is detailed in thesub-federal jurisdictions’ acts and laws respectingwildlife. Any authority not specified is considered“residual” and falls to the federal government,which is also responsible for wildlife on designatedfederal lands (i.e., national parks), all migratorywildlife that crosses international boundaries,marine mammals, and, in some instances, wherethe range or migration of a species occurs in2 or more provinces or territories. The federalSpecies at Risk Act (2002) may have applicationwhere provincial or territorial measures to protectendangered and threatened wildlife are consideredinsufficient. The Act authorizes designation ofthreatened species and identification of measuresto recover them. Exceptions and variations tothe foregoing exist across Canada – specially inQuebec (civil code derived from French law) andthe territories of Nunavut, Northwest Territories,and Yukon (territorial jurisdiction is more limitedthan is provincial in some matters) – but the basicmodel is that migratory, marine, and other federaltrust species fall to the federal government, andeverything else is within the purview of the provincesand territories. Federal, provincial, and territorialgovernments have established public wildlifeagencies (e.g., the federal Canadian Wildlife Service)to devise and implement conservation programs.Tacitly or explicitly, the fundamental tenets of theModel are accepted and practiced in Canada.Treaty Indians have jurisdiction over all animals ontheir Indian Reserves, except where endangeredspecies legislation may be applied, and manyaboriginal communities do not accept the legitimacyof any outside authority. In regards to aboriginalcommunities, courts in Canada are still definingmatters of governance. Rights of access to wildlifeby aboriginal people (i.e., they are allowed to takewildlife at any time on land to which they haveright of access) was confirmed in the ConstitutionAct of 1982. These rights may be abrogated bygovernment only after extensive consultation, andonly for purposes of sustaining wildlife populations.A restriction on access to wildlife on aboriginal landsapplies automatically to all Canadians.Systematic consultation among federal, provincial,territorial, and, more recently, aboriginal authoritiesis extensive. Complexities of Canadian law andtradition have made apparent to wildlife managersthat effective conservation programming requiresclose consultation among all jurisdictions. Fordecades, the annual Federal-Provincial WildlifeConference was a fixture in Canada; it now hasevolved into a structured contact among thejurisdictions through regular meetings of provincial,territorial, and federal wildlife-resource directorsemployed by public wildlife agencies. Other groupssuch as the Committee On the Status of EndangeredWildlife In Canada (COSEWIC) also operate on afoundation of inter-jurisdictional consultation andcooperation. In general, the goal of such groupsis to agree on basic policy and program initiatives,The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation6

but leave implementation to the legal authority,where it can be done in keeping with widely varyingcircumstances across Canada.Canada is signatory to several internationaltreaties and conventions, including the MigratoryBird Treaty with the U.S. and Mexico, its derivativeNorth American Waterfowl Management Plan, theConvention on International Trade in EndangeredSpecies of Fauna and Flora (CITES), and theRamsar Convention on Wetlands (RAMSAR) – theinternational treaty for maintaining wetlands ofinternational importance.Management authority over wildlife is public.Although laws differ widely among jurisdictionswith respect to captive animals, the basic principleis that wildlife is a public trust, and no privateownership is allowed. Landowners may be givenspecial access privileges in recognition of theirrole in sustaining populations of certain species,but only in accordance with public law. Privateconservation organizations have a vital role inconservation and work closely with public agencies.There are advisory boards in some provinces andterritories, but public stewardship prevails. Thegovernance model for wildlife conservation decisionmaking is typically at the (elected) ministeriallevel. Boards and commissions do not have thesignificant role in Canada that they do in the U.S.Canada’s political structure is based on the Britishparliamentary system, which affords less directparticipation in public affairs than does the Americancongressional system.Funding.— As mentioned above, Canada is governedunder (its derivative of) the British parliamentarysystem, of which a fundamental aspect is thegeneral revenue system of public finance, meaningno dedicated funds. All tax revenues, regardlessof source, go into a c

that wildlife conservation in North America could be described as a model was first articulated by Geist (Geist 1995, Geist et al. 2001), who coined the term "North American Model of Wildlife Conservation" ildlife conservation varies worldwide in its form, function, and underlying principles. In recent years, efforts have been directed