Transcription

The Importance of Being Monogamousmarriage and nation building in western canada to 1915

sarah carterThe Importanceof Being Monogamousmarriage and nation buildingin western canada to 19151the university of alberta press

Exclusive rights to publish and sell this book in printPublished byform are licensed to The University of Alberta Press. AllThe University of Alberta Pressother rights are reserved by the author. No part of theRing House 2publication may be produced, stored in a retrieval system,Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2E1or transmitted in any forms or by any means, electronic,mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior written consent of the copyright ownerandor a licence from The Canadian Copyright LicensingAU PressAgency (Access Copyright). For an Access CopyrightAthabasca Universitylicence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free:1 University Drive1-800-893-5777. An Open Access electronic version of thisAthabasca, Alberta, Canada T9S 3A3book is available on the Athabasca University Press website at www.aupress.ca.Copyright Sarah Carter 2008Printed and bound in Canada by Houghton BostonThe University of Alberta Press is committed to protectingPrinters, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.our natural environment. As part of our efforts, thisFirst edition, first printing, 2008book is printed on Enviro Paper: it contains 100% post-All rights reservedconsumer recycled fibres and is acid- and chlorine-free.A volume in The West Unbound: Social and CulturalThe University of Alberta Press and AU Press gratefullyStudies series, edited by Alvin Finkel and Sarah Carter.acknowledge the support received for their publishingprograms from The Canada Council for the Arts. Theyalso gratefully acknowledge the financial support of thelibrary and archives canadaGovernment of Canada through the Book Publishingcataloguing in publicationIndustry Development Program (bpidp) and from theAlberta Foundation for the Arts for their publishingactivities.Carter, Sarah, 1954–The importance of being monogamous : marriage andnation building in Western Canada to 1915 / Sarah Carter.(West unbound : social and cultural studies)Includes bibliographical references and index.ISBN 978–0–88864–490–91. Marriage—Canada, Western—History—19th76This book has been published with the help of a grantcentury. 2. Monogamous relationships—Canada,from the Canadian Federation for the Humanities andWestern—History—19th century. 3. Indian women—Social Sciences, through the Aid to Scholarly PublicationsCanada, Western—History—19th century.Program, using the funds provided by the Social Sciences4. Mormons—Canada, Western—History—19th century.and Humanities Research Council of Canada.5. Canada, Western—Social conditions—19th century.Titlepage photo: Métis married couple Sarah (née PetitI. Title.Couteau) and Joseph Descheneau, Camrose, Alberta,HQ560.15.W4C37 2008C2007–907579–7306.84’2209712c. 1905. (gaa na–3474–8)

For my mother:Mary Y. Carter

Now the first argument that comes ready to my hand is that the realhomestead of the concept “good” is sought and located in the wrong place:the judgment “good” did not originate among those to whom goodness wasshown. Much rather has it been the good themselves, that is the aristocratic,the powerful, the high-stationed, the high-minded, who have felt that theythemselves were good, and that their actions were good, that is to say of thefirst order, in contradistinction to all the low, the low-minded, the vulgar andthe plebian. It was out of this pathos of distance that they first arrogatedthe right to create values for their own profit, and to coin the names of suchvalues: what had they to do with utility?—friedrich nietzsche“Good and Evil, Good and Bad,” The Genealogy of Morals

Contentsxi Acknowledgementso n e1 Creating, Challenging, Imposing, and Defending theMarriage “Fortress”t w o19 Customs Not in Commonthe monogamous ideal and diverse marital landscapeof western canadat h r e e63 Making Newcomers to Western Canada Monogamousf o u r103 “A Striking Contrast Where Perpetuity of Union andExclusiveness is Not a Rule, at Least Not a Strict Rule”plains aboriginal marriagef i v e147 The 1886 “Traffic in Indian Girls” Panic and the Foundation ofthe Federal Approach to Aboriginal Marriage and Divorce

s i x193 Creating “Semi-Widows” and “Supernumerary Wives”prohibiting polygamy in prairie canada’s aboriginal communitiess e v e n231 “Undigested, Conflicting and Inharmonious”administering first nations marriage and divorcee i g h t279 ex

AcknowledgementsIn 1993 I first wrote an abstract sketching out some dimensions ofthis study for a conference paper proposal. The paper was not accepted.Undeterred, I’ve continued to work on this topic ever since althoughmany other projects and responsibilities have intervened. I am gratefulto the many people who helped me over many years and I hope I haven’tforgotten anyone. I would like to first acknowledge and thank myresearchers at the Universities of Calgary, Alberta and elsewhere (someof whom will likely have forgotten that they helped me with thisproject): Alana Bourque, Kristin Burnett, Peter Fortna, Patricia Gordon,Laurel Halladay, Michel Hogue, Kenneth J. Hughes (of Ottawa, not tobe confused with an old friend of the same name in Winnipeg), PernilleJakobsen, Nadine Kozak, Siri Louie, Melanie Methot, Ted McCoy, JillSt. Germaine, and Char Smith. While I did not have a Social Sciencesand Humanities Research Council of Canada standard research grantspecifically for this project, some of the research from two others (oneon Alberta women and another on Great Plains gender and land distribution history) spilled over and was lapped up by this project and I amvery grateful for these grants. The study was also enriched by the assistance, comments, suggestions and leads of many friends, colleagues andarchivists including Judith Beattie, Mary Eggermont, Keith Goulet, AliceKehoe, Maureen Lux, Bryan Palmer, Donald B. Smith, David E. Wilkins,H.C. Wolfart. Thanks to my father Roger Colenso Carter, Saskatoon, forhis comments on a final draft. Special thanks to the Calgary Institute forxi

the Humanities of the University of Calgary that provided importantintellectual and physical space during the year I spent there as a fellow.I am grateful to Rev. John Pilling for permission to use the Records ofthe Anglican Diocese of Calgary at the University of Calgary Archivesand Special Collections. Thanks to Sean England and Scott Andersonfor their careful editorial work, and to Lesley Erickson for compilingthe bibliography. Thanks to Erna Dominey and Peter Midgley for theirassistance with the many tasks involved in preparing the final version ofthe manuscript; thanks also to the anonymous readers of the originalsubmission for their comments and to Moira Calder for the index.I have given papers based on this research on many occasions overthe years and have found several to be significant moments in helpingme formulate my ideas and engage with audiences. Thanks to AdelePerry and other organizers of the 2002 conference “Manitoba, Canada,Empire: A Day of History in Honor of John Kendle,” to Joan Sangsterfor asking me to give the 2003 W.L. Morton Lecture at Trent University,to Georgina Taylor for asking me to speak at the Saskatoon Campus ofFirst Nations University in the spring of 2007 and to Joanna Dean forthe invitation to give the 2007 Shannon Lecture in History at CarletonUniversity.Earlier versions of some of this material has appeared in two articles:“Creating ‘Semi-Widows” and ‘Supernumerary Wives’: ProhibitingPolygamy in Prairie Canada’s Aboriginal Communities to 1900,” inContact Zones: Aboriginal and Settler Women in Canada’s Colonial Past,” ed.,Katie Pickles and Myra Rutherdale (Vancouver: University of BritishColumbia Press, 2005), 131–59; and “‘Complicated and Clouded’: TheFederal Administration of First Nations Marriage and Divorce Amongthe First Nations of Western Canada, 1887–1906,” in Unsettled Pasts:Reconceiving the West Through Women’s History, ed. Sarah Carter, LesleyErickson, Patricia Roome and Char Smith (Calgary: University of CalgaryPress, 2005): 151–78. I am grateful for permission to reprint this material.Special thanks as always to my partner, Walter Hildebrandt, for hissupport and comments during the many years of this project and I hopehe hasn’t tired of (hearing about) monogamy. The book is dedicated toxiiAcknowledgements

my mother, Mary Y. Carter, who had a long career as a lawyer, magistrateand judge in Saskatoon and was herself a “pioneer” in family law inWestern Canada.Acknowledgementsxiii

List of AbbreviationsapscmsdiahbcnwcnwmpmsrccAborigines Protection SocietyChurch Missionary Society (of the Anglican Church)Department of Indian AffairsHudson’s Bay CompanyNorth West CompanyNorth West Mounted PoliceMoral and Social Reform Council of Canadaxv

one

Creating, Challenging,Imposing, and Defendingthe Marriage “Fortress”

“Marriage ‘Fortress’ Guards Way of Life”; this was theheadline of a 3 June 2006 editorial by Ted Byfield in the CalgarySunday Sun. The highlighted quotation read, “A viable societydepends on stable families, which depend on stable marriages.”The next day marriage was once again on the front page, this timein Toronto’s Globe and Mail, as Prime Minister Stephen Harper hadannounced that Members of Parliament would vote in the fall ona motion asking if they wanted to reopen debate on the contentious issue of same-sex marriage. That same month President GeorgeW. Bush called for a ban on same-sex marriage in the United States.Conservative authors, politicians, and religious leaders in NorthAmerica are continually informing us that we are living at a time ofprofound social and cultural crisis, when the erosion of the institution of marriage is eating away at society’s very foundations.1 Theyinsist on one definition of marriage, the union of one man and onewoman (hopefully for life) to the exclusion of all others: a definitionrepresented as ancient, universal, and founded on “common sense.”2the importance of being monogamous

Behind such notions is a wistful nostalgia for an imaginary simplertime, when gender roles were firmly in place with the husband as familyhead and provider, and the wife as the dependent partner—obedient,unobtrusive, and submissive. According to Byfield, marriages used to bemore stable because nearly every family depended on one income, sothat the “rival interests of two competing careers did not constantlywork to tear the marriage apart.” He also blamed women for the majorityof divorces as he found they tended to be the ones to kick out their“astonished and utterly devastated husband[s]” simply because they are“disillusioned” or have “disappointed expectations.” Marriage has beena powerful tool for shaping the gender order; those who bemoan theerosion of marriage mainly regret the erosion of the powerful husband/dependent wife model.A main point of this study is that the “traditional” definition of marriage is not as ancient and universal as conservative thinkers typified byTed Byfield would have us believe. In Public Vows: A History of Marriageand the Nation, a 2000 study that focuses on the United States, NancyCott argues that the Christian model of lifelong monogamous marriagewas not a dominant worldview until the late nineteenth century, that ittook work to make monogamous marriage seem like a foregone conclusion, and that people had to choose to make marriage the foundation forthe new nation.2 Even then, Cott argues, this dominant monogamousvision was contested, demonstrating how legislation, court cases, andcommunity pressure curbed and contained alternative forms of marriage.By the late nineteenth century there was much less flexibility in themeaning of marriage, and far fewer alternatives to monogamy. Relationsbetween a wife and husband were more starkly inequitable than everbefore. Gender is at the heart of Cott’s analysis; marriage forged meanings of men and women, and the state shaped the gender order throughthe imposition of a particular model of marriage. Cott writes: “the wholesystem of attribution and meaning that we call gender relies on and to agreat extent derives from the structuring provided by marriage. Turningmen and women into husbands and wives, marriage has designated theway both sexes act in the world.”3 Cott also argues that to be interestedin American identity is to be interested in marriage. Marriage served as aCreating, Challenging, Imposing, and Defending the Marriage “Fortress”3

metaphor for voluntary allegiance and permanent union, the foundation for national morality. This was contrasted with the evils of othermodels of marriage and governance such as polygamy and despotism.My study shows that marriage was also part of the national agenda inCanada—the marriage “fortress” was established to guard our way oflife. To be interested in Canadian identity is to be interested in marriage.In the late nineteenth century there was widespread anxiety about thestate of marriage, family, and home: all perceived to be the cornerstonesof the social order. The very foundation of the nation was thought to beunder threat. The remedy was to shore up the fortress of marriage, permitting no deviations, no divorce, and no remarriage, thereby ensuring“the maintenance within Canada of the purity of the marriage state,”and protecting Canadians from the adoption of the “demoralizing anddegrading” marriage and divorce laws of the United States.4 Indeed, itwas considered vital to defend the “fortress” of Canadian marriage inNorth America against the pernicious, corrupt, and immoral influenceof the United States, where it was understood that the marriage tie wasloose and lax. Canada would not repeat the American mistake. Canadawould protect its marital purity. Politicians, social reformers, and judgeswidely agreed that marriage was a sacred institution that supported thewhole social fabric and was essential to peace, order, and good government in Canada. It would be a “deadly stab upon the constitution of theDominion” to relax laws of marriage and divorce.5Western Canada presented particular challenges to the national agendain the late nineteenth century, as the region was home to a diverse population with multiple definitions of marriage, divorce, and sexuality—theChristian, heterosexual, and monogamous ideal had to be made the soleoption.6 Historian Adele Perry has suggested that the term “Christianconjugality—by which I mean lifelong, domestic, heterosexual unionssanctioned by colonial law and the Christian church” best describesthe model of marriage that missionaries and others sought to imposeon this diversity.7 Before the late nineteenth century, the predominance of this model was not a foregone conclusion, and many marriagesdeparted from the often-quoted “classic” nineteenth-century definitionof marriage presented by the English judge, Sir James O. Wilde (Lord4the importance of being monogamous

Penzance). He wrote, “Marriage, as understood in Christendom may be defined as the voluntary union for life of one man and one woman,to the exclusion of all others.”8 In Western Canada, however, thereexisted diverse forms of marriage among Aboriginal people, includingmonogamy, polygamy, and same-sex marriage, and no marriage neededto be for life as divorce was easily obtained and remarriage was acceptedand expected. There were varied types of marriages to be found inthe interracial “fur-trade” society, and many Métis marriages drew onAboriginal precedent and reflected the same flexibility, but some alsodrew on the informal means of gaining community sanction for divorceand remarriage that persisted in Europe to the mid-nineteenth century.New arrivals to the west had marriage laws and domestic units thatdeparted from the monogamous model. These multiple definitions ofmarriage and family formation posed a threat, endangering convictionsabout the naturalness of the monogamous and nuclear family model.Among these newcomers, the Mormons, who practiced polygamy, werethe clearest example of those who challenged the monogamous ideal, butthere were others with alternative views of marriage and divorce. Somegroups wished to alter relations between men and women, providingmore options and freedom for women than were permitted under themonogamous model. The preponderance of single men among theimmigrants represented yet another threat to the heterosexual monogamous order as the foundation for the nation. Single women, althoughpresent in much smaller numbers, were also a menace to this foundation. Perceived as the most dangerous set of “others,” however, werethe large numbers of Americans who poured north into Canada’s West,providing models of alternative approaches to marriage and divorce.As in other British colonial settings, architects of this new region ofCanada were determined to proclaim that their heritage was the most“civilized” and advanced. Claiming to have superior marriage laws thatsupposedly permitted women freedom and power was (and continuesto be) a common boast of imperial powers. As historian Bettina Bradburyhas shown in her study, “Colonial Comparisons: Rethinking Marriage,Civilization and Nation in Nineteenth-Century White Settler Societies,”colonial politicians distinguished the “civilized heritage” of their marriageCreating, Challenging, Imposing, and Defending the Marriage “Fortress”5

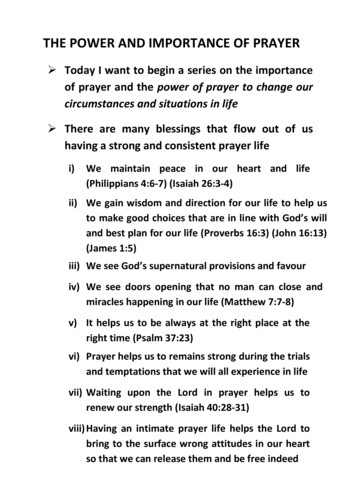

laws from that of “ancient barbarians, ‘heathens,’ and other peoples theycharacterized as uncivilized. They also took pains to dissociate theirown future from what they represented as the dangerous results of marriage regimes in some other Western societies.”9 The United States wasan example to be avoided. The politicians and other makers of WesternCanada confronted and had to fight off alternative marriage laws on allfronts—from the ancient inhabitants, from the Métis who were theoffspring of two hundred years of intermarriage, from newly arrivingEuropean immigrants and from the US. “Proper” marriage would helpmaintain the new settlers’ social and sexual distance from the Aboriginalpopulation, and it would forge the new settler identity.10 Insisting onthe superiority of British, Christian and common-law marriage played acritical role in the forging of a British Canadian identity in WesternCanada, and it also played a critical role in the consolidation of statepower in that region.11A variety of forces combined to contain and undermine alternativelogics and to ensure the ascendancy of the monogamous, intra-racial modelin Western Canada, seen as vital to the stability and prosperity of thenewest region of the Dominion. As Sylvia Van Kirk has shown, hostilityand prejudice toward the marriages of Aboriginal women and nonAboriginal men grew from the mid-nineteenth century.12 These attitudeswere exemplified in colonial discourses that denounced race-mixing, inthe courts, and in missionary circles. Advice books and works of fiction,along with journal and newspaper articles, all further promoted themonogamous model as the key institution to ensure the status and happiness that white women enjoyed. Through sermons, missionary work,lay organizations, and publications, the dominant Christian churchesalso promoted this ideal. Single and divorced women were stigmatizedwhile sympathy was expressed for the lonely, unkempt bachelors of thewest who needed wives to transform their lives and farms.Federal land laws deliberately fostered “family farms,” with the monogamous couple at the core of the vision. Single women were excluded The ideal building block for Western Canada: the monogamous couple. Mary and RobertJamison’s wedding portrait, c. 1879, when the new Mrs. Jamison was sixteen. The Jamisons camefrom Ontario in 1884 and settled in the Pine Creek, Alberta area. (gaa na–3571–13)6the importance of being monogamous

Creating, Challenging, Imposing, and Defending the Marriage “Fortress”7

from qualifying for homestead land as this permitted women an opportunity to be free of marriage. Instead, single white women were importedinto the region in large numbers, as domestics, but also as wives andmothers of the “race.” Federal legislation was introduced to prohibitalternative marriages, such as Mormon polygamy, while North-WestTerritories legislators moved to legalize Doukhobor and uakermarriage in order to draw these groups into the obligations and responsibilities set by the state for married people. The enforcement of bigamylaws, and the near impossibility of divorce in Canada, also ensured theascendancy of the monogamous model. The Canadian monogamousmodel of marriage, idealized as an institution that cherished and elevatedwomen, left many people impoverished and alone, often with childrento support. They were unable to get a divorce from a spouse who desertedthem, or to remarry even after years of desertion or separation. Therewere many unhappily “attached” yet unattached people throughout thewest, and the greater burden fell on deserted wives.In the more heavily populated areas of Canada, this widespread anxietyabout the state of marriage has been attributed to fears of a disintegratingsocial order in the wake of industrialization, rural depopulation, andurbanization. In Western Canada, however, there were different reasonsfor anxiety over marriage. It was a region undergoing colonization, andin most areas Aboriginal people outnumbered Euro-Canadian colonizersat the outset of the time period examined in this study. Before that therehad been a period of over two hundred years when Aboriginal womenhad married European and Canadian men, and their offspring had marriedand mingled, creating a sizeable Métis population. Interracial marriagewas deprecated in the post-1870 order, however, and a continual threadrunning through this study is the persistent calls for legislation that wouldprohibit and police such unions. The monogamous white husband-andwife team was to be the basic economic and social building block of thewest. They were to help produce not only crops, but also the future “race”of Canadians who would populate the west. The health and wealth ofthe new region, and that of the entire nation, was seen as dependent onthe establishment of the Christian, monogamous, and lifelong modelof marriage and family—the “white life for two.”13 Irregular domestic8the importance of being monogamous

arrangements imperilled progress, prosperity, and the health of the“race.” Much work was required to realize the monogamous vision.These are the themes and arguments of chapters two and three ofthis book, which then turns to the complicated history of the imposition of the monogamous model on prairie First Nations with particularfocus on women. The context provided in the first two chapters is vitalto an understanding of this initiative, which was but one componentof a much broader program to impose the monogamous model on thediverse people of Western Canada. The same cluster of laws, attitudes,and expectations deposited on First Nations were similarly applied toeveryone else. Aboriginal people were compelled to conform to thelaws, attitudes, and expectations that governed all married people in therest of Canada. These expectations included the gender roles encodedin the monogamous model of the submissive, dependent wife and thepowerful head-of-household husband. The broader context is importantto understanding, for example, that both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal women who “lost their virtue” before marriage, or who engaged inextramarital relations, were regarded as prostitutes “utterly destitute ofmoral principle.”14 Marriage was virtually indissoluble in Canada, withdivorce nearly impossible for all but a wealthy few, and this rigid attitude was imposed on the First Nations. Similarly the bigamy laws, alsoapplied to the First Nations, meant that deserted wives or husbands,even if they never heard from a spouse again, might never be able toremarry if they knew the spouse to be alive. Under the new legal regime,many Aboriginal women joined the ranks of deserted women with children, who were unable to remarry.Through the Department of Indian Affairs (dia) and other associatedarms of the federal government, the Canadian state was able to invadethe domestic affairs of First Nations societies and impose these laws,attitudes, and expectations to a much greater extent than was possiblewith other communities. There were destructive consequences to thisinvasion, but the power of the state was also limited and contested. Thisstudy points to the persistence of Aboriginal marriage and divorce law,and to the determined insistence of Aboriginal people that they had theright to live under their own laws. This reflects another present-dayCreating, Challenging, Imposing, and Defending the Marriage “Fortress”9

issue frequently in the news as I researched and wrote this book—theneed to recognize Canada’s Aboriginal tradition of law and justice, a“third” legal tradition alongside the British common law and Frenchcivil law traditions according to Liberal Minister of Justice Irwin Cotler.Cotler stated in 2004: “We have to start thinking in terms of pluralisticlegal traditions of this country. Having a bi-jural, civil law and commonlaw [system] already makes us rather unique in the world. Enlargingthat to also have an indigenous legal tradition and maybe being a worldleader in mainstreaming that indigenous legal tradition, will mean thatwe can make a historic contribution—not only domestically, but internationally.”15 Aboriginal marriage law continued to function throughoutthe period of this study and far into the twentieth century. The government, and to some extent the courts, upheld the validity of Aboriginalmarriage law, but did not recognize their divorce law.The marriage laws of Plains Aboriginal people were complex and flexible, permitting a variety of conjugal unions. There is debate amonghistorians and anthropologists as to whether the various kinds of conjugalunions of Indigenous people can be called “marriage.” My position is thatthey can, and that there is no single definition of marriage, as it changesover time and not all cultures share the same definitions. Aboriginalfamily law also permitted divorce and remarriage. The ease with whichdivorce was acquired limited the extent of a husband’s power over awife. The divorce of unhappy people, and their subsequent remarriage,was vital to the well-being of the family and the community. Virtuallyeveryone had a spouse, except those who did not desire to be married.There were no single mothers, and concepts such as “illegitimate” children were unknown. Aboriginal marriage and divorce law was not wellunderstood by non-Aboriginal outsiders, and it was widely presented asan institution that exploited and subordinated women. Polygamy wasparticularly singled out for criticism, as it allegedly left wives wretchedand jealous as they were controlled, abused, and hoarded by a male elite.Because marriage did not appear to be a binding contract in the EuroCanadian sense, wives were not seen as “true” wives, and they werelabelled prostitutes if they had more than one marital or sexual partner.10the importance of being monogamous

Saving Aboriginal women from these marriages was one of the mainjustifications for colonial intervention in their domestic affairs—theytoo could enjoy the lofty and cherished status of white women. Similarjustifications were frequently used for intervention in Afghanistan andIraq as I wrote this book; as in earlier colonial times, the status of womencontinues to be manipulated as a political and rhetorical strategy tojustify imperial expansion. The women themselves were not consulted,nor was any concern shown for the actual fate of either the women ortheir children as a result of the upheaval of this intervention.Despite the colonial critique of Aboriginal marriage, an important1867 legal decision in the case of Connolly v. Woolrich held that Aboriginalmarriage law was valid, at least in Aboriginal territory. Using this case asthe legal precedent, the dia adopted the policy in 1887 that Aboriginalmarriages would be recognized as valid, while Aboriginal divorces wouldnot be so recognized (even though the decision in Connolly v. Woolrichleft open the possibility of validating Aboriginal divorce law). The diawas compelled to articulate a policy at this time in the light of sensational allegations from the west of a “traffic in Indian girls,” which wasbrought to the attention of the Canadian government by the Londonbased Aborigines Protection Society in England. The allegations wereinspired by W.T. Stead’s revelations of girls being trafficked in London, asensational claim that had repercussions throughout the British Empire.Conditions in Western Canada just at that time provided fertile soil inwhich to sow these hysterical allegations.In the mid-1880s, new settlers to the west were calling for social andspatial segregation and for measures that would curb the power of theMétis, seen as a dangerous and subversive force. They had fomented twoarmed resistances, and they were also a drain on the public purse as theyreceived land and money scrip from the government. Fear and anxietywas similarly generated about “Indian depredations,” and there werecalls for “Indian removal” to more remote northern areas, as well as forthe strict enforcement of the pass system to contain people on reserves.Aboriginal women’s alleged promiscuity, their purported luring ofwhite men to depravity, and their presence in the settlements wereCreating, Challenging, Imposing, and Defending the Marriage “Fortress”11

central components of this hysteria. Authorities at the highest levels ofgovernment shared these views, and they were contained in the government position expressed in an 1887 order-in-council that was to be

community pressure curbed and contained alternative forms of marriage. By the late nineteenth century there was much less flexibility in the meaning of marriage, and far fewer alternatives to monogamy. Relations between a wife and husband were more starkly inequitable than ever before. Gender is at the heart of Cott's analysis; marriage .