Transcription

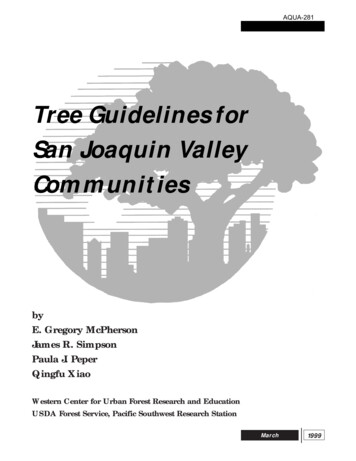

AQUA-281Tree Guidelines forSan Joaquin ValleyCommunitiesbyE. Gregory McPhersonJames R. SimpsonPaula J. PeperQingfu XiaoWestern Center for Urban Forest Research and EducationUSDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research StationMarch1999

AQUA-281AcknowledgementsThis study was made possible by a grant from the Local GovernmentCommission and portions of funding provided by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 9, the International Society ofArboriculture Research Trust, the City of Modesto, and the Elvinia J.Slosson Fund.Todd Prager (UC, Davis), Chuck Gilstrap (City of Modesto), andDave Hallum (City of Fresno) provided technical assistance andvaluable information for this report. Larry Costello (UC CooperativeExtension) and Jim Clark (HortScience Inc.) provided helpful reviewsof this work.Western Center for Urban Forest Research and EducationUSDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Stationc/o Department of Environmental HorticultureUniversity of CaliforniaDavis, CA 95616-8587web: www.pswfs.gov/units/urban.htmlDepartment of Land, Air, and Water ResourcesUniversity of CaliforniaDavis, CA 95616Local Government Commission1414 K St., Suite 250Sacramento, CA 95814-3929 (916) 448-1198 fax (916) 448-8246web: www.lgc.org/energy

AQUA-281Tree Guidelines forSan Joaquin ValleyCommunities March 1999byE. Gregory McPhersonWestern Center for Urban Forest Research and EducationUSDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research StationJames R. SimpsonWestern Center for Urban Forest Research and EducationUSDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research StationPaula J. PeperWestern Center for Urban Forest Research and EducationUSDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research StationQingfu XiaoDepartment of Land, Air, and Water ResourcesUniversity of California, DavisEditing and DesignDave Davis

AQUA-281Table of ContentsExecutive Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101. Identifying Benefits and Costs ofUrban and Community ForestsEnergy Conservation Potential . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide Reductions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12Improving Air Quality . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13Reducing Stormwater Runoff . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13Other Benefits and Property Values . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14Costs of Planting and Maintaining Trees . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15Conflicts with Urban Infrastructure . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16Waste Disposal and Irrigation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 172. Quantifying Benefits And Costs of Tree ProgramsProcedures and Assumptions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19Benefits . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21Costs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25Results: Net Benefits, Average Annual Costs and Benefits . . . . . . . 273. General Guidelines for Siting and Selecting TreesResidential Yard Trees . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34 Maximizing Energy Savings from Shading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34 Locating Windbreaks for Heating Savings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35Trees in Public Places . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36 Locating and Selecting Trees to Maximize Climate Benefits . . . 36General Guidelines for Establishing Healthy Trees . . . . . . . . . . . . 39for Long-Term Benefits4. Program Design and Implementation GuidelinesProgram Design and Delivery . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40Increasing Program Cost Effectiveness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43 Increasing Energy Savings and Other Benefits . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43 Reducing Program Costs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43Sources of Technical Assistance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44Grant Programs in Urban and Community Forestry . . . . . . . . . . . 485. Trees for San Joaquin Valley Communities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 496. References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56Appendix A. Estimated Benefits and Costs for a Large, . . . . . . . . . 60Medium, and Small Tree for 40 Years after PlantingAppendix B. Funding and Program Resources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64for Local GovernmentsTree Guidelines

AQUA-281Executive SummaryExecutive SummarySan Joaquin Valley Communities will be among the fastest growing communities in the state during the next decade. The role of urban forests —trees in parks, yards, public spaces, and along streets — to improve environmental quality, increase the economic, physical and social health of communities, and foster civic pride will take on greater significance as communities strive to preserve and improve their quality of life in the face of thisgrowth. Urban and community forestry has been recognized as a cost effective means to address a variety of important community and national issuesfrom improving air quality to combating global warming.This guidebook analyzes the multitude of benefits thattrees can provide to communities and residents. Bydetermining the community and home owner savingsfrom planting trees and subtracting the cost, this studyfound that trees more than pay for themselves. Over a40 year period, after subtracting costs, every large treeproduces savings of approximately 2,000. Thisamount decreases with the tree's size with mediumtrees saving 1,000 and small trees breaking even.Trees can have far reaching affects on the quality of airand water in our communities, on the amount ofmoney we spend to cool and heat our houses, on thevalue of our property, and on the attractiveness of ourneighborhoods and public spaces. They affect ourmoods and our health, as well as the health of our children.This guidebook addresses the benefits of urban andcommunity forests and how you can reap these benefits for your community, your neighborhood, andyour family including:Who Should Read This GuideLocal Elected OfficialsPublic Works EmployeesCity and County PlannersDevelopers and BuildersArchitects and Landscape ArchitectsEnergy ProfessionalsAir & Water Quality ProfessionalsHealthcare AdvocatesHomeownersNeighborhood Activists and OrganizersArboristsEnvironment AdvocatesCommunity ForestersTree Advocacy OrganizationsConcerned CitizensvvvImproving environmental quality by planting trees.vDeveloping and promoting tree planting and maintenanceprograms in your community.vFinding sources of funding and technical assistancefor planting trees in your community.Planting trees to reduce energy consumption and save money.Choosing tree species that reduce conflicts with power lines, sidewalksand buildings.San Joaquin Valley communities can promote energy efficiency through treeplanting and stewardship programs that strategically locate trees to shadebuildings, cool urban heat islands, and minimize conflicts with power linesand other aspects of the urban infrastructure. Also, these same trees can pro-Tree Guidelines1

AQUA-281Executive Summaryvide additional benefits by reducing atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2),improving air quality, reducing stormwater runoff, increasing property values, enhancing community attractiveness, and promoting human health andwell-being. The simple act of planting trees provides opportunities to connectresidents with nature and with each other. Neighborhood tree plantings andstewardship projects stimulate investment by local citizens, business, and government in the betterment of their communities.Energy ImpactsRapid urbanization of cities during the past 50 years has been associatedwith a steady increase in downtown temperatures of about 1 F perdecade. As temperature increases, energy demand for cooling increases as docarbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel power plants, municipal waterdemand, unhealthy ozone levels, and human discomfort and disease.Urban forests improve climate andconserve building energy use by:vShading, which reduces the amount of radiantenergy absorbed and stored by built surfaces,vEvapotranspiration, which converts liquid waterin leaves to vapor, thereby cooling the air, andvWind speed reduction, which reduces theinfiltration of outside air into interior spaces.Trees and other greenspace may lower air temperatures 5-10 F. Because of the San JoaquinValley’s hot, dry summer weather, potentialcooling savings from trees are among the highest in the nation. Computer simulations for anenergy-efficient home in Fresno indicate thatshade from two 25-foot tall trees on the westside and one on the east side are estimated tosave 75 each year. Evapotranspirational cooling from these three trees is estimated toincrease savings by another 28.Air Quality ImpactsUrban forests can reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) in two ways.Trees directly store CO2 as woody and leafy biomass while they grow.Trees around buildings can also reduce the demand for heating and air conditioning, thereby reducing emissions associated with electric power production.Urban trees provide direct air quality benefits by:vAbsorbing gaseous pollutants (ozone, nitrogen oxides)through leaf surfaces,vvvIntercepting particulate matter (e.g., dust, ash, pollen, smoke),Releasing oxygen through photosynthesis, andTranspiring water and shading surfaces, which lowers local air temperatures, thereby reducing ozone levels.Trees can emit various biogenic volatile organic compounds that can contribute to ozone formation. The ozone forming potential of different treespecies varies considerably and can be found in the tree selection chapter.By shading asphalt surfaces and parked vehicles trees reduce emission ofhydrocarbons that come from leaky fuel tanks and worn hoses as gasoline2Tree Guidelines

AQUA-281Executive Summaryevaporates. These evaporative emissions are a principal component of smogand parked vehicles are a primary source.Water Quality ImpactsUrban stormwater runoff is a major source of pollution entering SanJoaquin Valley rivers and lakes. Trees improve water quality by:vIntercepting and storing rainfall on leaves and branch surfaces, therebyreducing runoff volumes and delaying the onset of peak flows,vIncreasing the capacity of soils to infiltrate rainfall and reduceoverland flow, andvReducing soil erosion by diminishing the impact of raindropson barren surfaces.Urban forests can provide other water benefits. Irrigated tree plantations canbe a safe and productive means of wastewater disposal. Reused wastewatercan recharge aquifers, reduce stormwater treatment loads, and create incomethrough sales of wood products.Social Impacts from TreesvAbate noise, by absorbing high frequency noise which are most distressing to people,vvCreate wildlife habitat, by providing homes for many types of wildlife,Reduce exposure to ultraviolet light, thereby lowering the risk ofharmful health effects from skin cancer and cataracts,Provide pleasure, whether it be feelings of relaxation, or connectionto nature,Provide important settings for recreation,Improve individual health by creating spaces that encourage walking,Create new bonds between people involved in tree planting activities,Provide jobs for both skilled and unskilled labor for planting andmaintaining community trees,Provide educational opportunities for residents who want to learnabout nature through first-hand experience, andIncrease residential property values (studies indicate people arewilling to pay 3-7% more for a house in a well-treed neighborhoodversus in an area with few or no trees).vvvvvvvUrban Forest CostsCosts for planting and maintaining trees vary depending on the nature oftree programs and their participants. Generally, the single largest expenditure is for tree trimming, followed by tree removal/disposal, and tree planting. An initial analysis of data for Sacramento and other cities suggests thathouseholds typically spend about 5-10 annually per tree for pruning,removal, pest/disease control, irrigation, and other tree care costs.Tree Guidelines3

AQUA-281Executive SummaryOther costs associated with urban trees include:vvvPavement damage caused by roots,vIrrigation costs.Flooding caused by leaflitter clogging storm sewers,Green waste disposal and recycling (can be offset byavoiding dumping fees and purchases of mulch), andCost effective strategies to retain benefits from large street trees while reducing costs associated with root-sidewalk conflicts are needed. The tree selection list in Chapter 6 contains information on the rooting characteristics ofrecommended trees.Residential Tree Selection and Location for Solar ControlThe ideal shade tree has a fairly dense, round crown with limbs broadenough to partially shade the roof. Given the same placement, a large treewill provide more building shade than a small tree. Deciduous trees allow sunto shine through leafless branches in winter.General Tree PlantingRecommendations include:vTrees on the west and northwest sidesof homes provide the greatest energybenefit; trees on the east side of homesprovide the next greatest benefit,vPlant only deciduous trees on the southside of homes to allow winter sunlightand heat,vvPlant evergreen trees as windbreaks,vShading your air conditioner can reduceits energy use, but do not plant vegetation so close that it will obstruct airflow around the unit,vKeep trees away from overhead powerlines and do not plant directly aboveunderground water and sewer lines.4Shade trees can make paved drivewaysand patios cooler and more comfortable spaces,When selecting trees, match the tree's water requirements with those of surrounding plants. Also, matchthe tree's maintenance requirements with the amount ofcare different areas in the landscape receive.Conifers are preferred over deciduous trees for windbreaks because they provide better wind protection.The ideal windbreak tree is fast growing, visuallydense, and has stiff branches that do not self-prune.Pines, cypress, and oak are among the best windbreaktrees for San Joaquin Valley communities.The right tree in the right spot saves energy. In midsummer, the sun shines on the northeast and east sidesof buildings in the morning, passes over the roof nearmidday, then shines on the west and northwest sides inthe afternoon. Air conditioners work hardest duringthe afternoon when temperatures are highest andincoming sunshine is greatest. Therefore, a home's westand northwest sides are the most important sides toshade. In San Joaquin Valley communities, the east sideis the second most important side to shade.Trees located to shade south walls can block wintersunshine and increase heating costs, because duringwinter the sun is lower in the sky and shines on thesouth side of homes. The warmth the sun provides isan asset, so do not plant evergreen trees that will block southern exposuresand solar collectors.Tree Guidelines

AQUA-281Executive SummaryTree Location and Selection in Public PlacesLocate trees in common areas, along streets, in parking lots, and commercial areas to maximize shade on paving and parked vehicles. By coolingstreets and parking areas, they reduce emissions from parked cars that areinvolved in smog formation. Large trees can shade more area than smallertrees, but should be used only where space permits. Remember that a treeneeds space for both branches and roots.CO2 reductions from trees in common areas are primarily due to sequestration (storage in biomass). Fast-growing trees sequester more CO2 initiallythan slow-growing trees, but this advantage can be lost if the fast-growingtrees die at younger ages. Large growing trees have the capacity to store moreCO2 than do smaller growing trees. To maximize CO2 sequestration, selecttree species that are well-suited to the site where they will be planted.Contact your local utility company before planting to locate undergroundwater, sewer, gas, and telecommunication lines. Note the location of powerlines, streetlights, and traffic signs, and select tree species that will not conflictwith them. Keep trees at least 30 feet away from street intersections to ensurevisibility. Avoid locating trees where they will block illumination fromstreet lights or views of street signs in parking lots, commercial areas,and along streets. Avoid planting shallow rooting species near sidewalks, curbs, and paving.The ideal public tree is not susceptible to wind damage and branchdrop, does not require frequent pruning, produces little litter, is deeprooted, has few serious pest and disease problems, and tolerates awide range of soil conditions, irrigation regimes, and air pollutants.Because relatively few trees have all these traits, it is important tomatch the tree species to planting site by determining what issues aremost important on a case-by-case basis.Program DesignAsuccessful shade tree program is likely to be community-wide andcollaborative. Fortunately, lessons learned from urban and community programs throughout the country can be applied to avoid pitfalls and promote success.Tree planting is a simple act, but planning, training, selecting species,and mobilizing resources to provide ongoing care require considerableforethought. Successful shade tree programs will address all theseissues before a single tree is planted.What Can Local Governments Do?A Checklistfor DesigningYour Tree ProgramvEstablish the OrganizingGroupvvDraw a Road MapvProvide Timely, Handson Training andAssistancevvNurture Your VolunteersvDevelop a List ofRecommended TreesvvCommit to Stewardshipvocal government has a long history of preserving and expandingthe urban forest. Below are some recommended steps for furtherlocal government involvement. Appendix B provides more background materials, contact information and a list of funding resources.LSend Roots into theCommunityObtain High-QualityNursery StockUse Self-Evaluation toImproveEducate the PublicTree Guidelines5

AQUA-281Executive SummaryvTRequire Shade Trees in New Developmentrees can help to reduce energy costs, improve air and water quality, andprovide urban residents with a connection to nature.Trees reduce cooling needs during hot summers by shading buildings andcooling the air through evapotranspiration. Computer simulations show thatan energy-efficient home in Fresno could save 103 in annual energy costs iftwo 25-foot tall trees were placed on the west side of the home and an additional tree was planted on the east side. Properly placed trees can also act aswind barriers, keeping outside air from entering interior spaces, potentiallyreducing both heating and cooling needs.Tree selection and placement is critical to optimizing the potential benefits oftrees. See Chapter 3, “General Guidelines for Siting and Selecting Trees,” formore information. The City of Redding requires one new tree to be plantedfor every 500 sq. ft. of closed space for residential, one per 1000 sq. ft. forcommercial, and one per 2,000 sq ft. for industrial. Credits are given for thepreservation of existing trees.The City of Escalon is requiring street trees in its new Farinelli Ranch subdivision to shade street pavement, lower ambient temperatures and reducethe cooling needs of neighboring homes. Narrowing streets increased shadecover while lowering development costs. These combined actions are projected to reduce annual energy use for cooling by 18% per home.vRequire Shade Trees in Parking LotsEmissions from parked cars are a significant contributor to smog. By shading asphalt surfaces and parked vehicles, trees reduce the emission ofhydrocarbons that occur when gasoline evaporates from leaky fuel tanks andworn hoses.The City of Davis requires that 50 percent of paved parking lot surfaces beshaded with tree canopies within 15 years of the building permit being issued.The City of Redding requires one tree per four parking spaces.Proper planting procedures, including an adequate planting area and effectiveirrigation techniques, along with ongoing monitoring and maintenance areessential to the survival and vitality of parking lot trees. The City of Davis iscurrently considering using a community tree group, Tree Davis, to assist inannual inspections of parking lot trees.Davis is also pursuing innovative construction methods that would provideparking lot trees with a larger rooting area without compromising the structural integrity of the paved surfaces. Soils underneath parking lots are usually very compact, offering parking lot trees limited root space. This can compromise the ability of parking lot trees to survive and thrive.As part of a parking lot renovation and plaza construction project in downtown Davis, the City plans to install a structural soil mix around the parkinglot and plaza trees as an alternative to standard aggregate base. The structural6Tree Guidelines

AQUA-281Executive Summarysoil mix, developed by Cornell University, provides the compaction neededbelow parking lot paving surfaces while providing an accessible rooting environment for the parking lot trees.vAdopt a Tree Preservation OrdinanceThis ordinance can be used to protect and enhance your community’surban forest. Many cities and counties require a permit to remove a treeor build, excavate or construct within a given distance from a tree. At leastone tree should be planted for every tree that is removed.vHire or Appoint a City Forester/ArboristThe California Energy Commission’s Energy Aware Planning Guide recommends that a single person should be responsible for urban tree programs,including “planting and maintenance of public trees, tree planting requirements for new development, tree protection, street tree inventories and longrange planning.” A number of cities maintain full-time arborists who areemployed through the Public Works or Parks and Recreation Departments.vConduct a Street Tree Inventory andEstablish a Maintenance ProgramAhealthy urban forest requires regular maintenance. A street tree inventory identifies maintenance needs. A management plan prioritizes spendingfor pruning, planting, removal and protection of trees in the community.vAdopt a Landscaping Ordinance to EncourageEnergy Efficiency and Resource ConservationTrees placed in proper locations can provide cooling relief and reduce summer air-conditioning needs. Shrubs, vines and ground covers can also beused to lower solar heat gain and reduce cooling needs. Given the long, dryand hot summers of the San Joaquin Valley, choosing inappropriate speciesfor the local climate can result in a large demand for water and chemicalinsecticides and herbicides.The City of Irvine’s Sustainability in Landscaping Ordinance outlines guidelines for developing and maintaining landscapes that conserve water andenergy, optimize carbon dioxide sequestration, increase the production ofoxygen, and lower air conditioning demands. The ordinance encourages theCity to develop and promote programs and activities that educate residentsabout the benefits of sustainable landscaping. The ordinance also discouragesthe use of inorganic fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides.vUse Tree Planting to Strengthen Communitiesand Increase Resident InvolvementResearch shows that residents who have participated in tree planting eventsare more satisfied with trees and their neighborhood than are residentswhere trees have been planted by the city, a developer, or volunteer groupswithout resident involvement.Tree Guidelines7

AQUA-281Executive SummaryThrough the City of Long Beach’s Neighborhood Improvement TreeProject, city staff worked with neighborhood groups, the ConservationCorps of Long Beach, and local businesses to plant trees in physically distressed neighborhoods during the spring of 1998. Five hundred volunteershelped to plant over 800 trees. City staff report that the event provided localresidents with a sense of empowerment and helped to strengthen community ties.vUtilize Funding Opportunities to PlantTrees and Maintain the Urban ForestCalifornia ReLeaf, the urban forestry division of the Trust for Public Land,maintains an extensive list of funding resources for urban forestry andeducation projects. See Chapter 4 and Appendix B for more information.The Energy Aware Planning Guide proposes including street tree planting inthe capital budget for road building which may help to secure funding.Cities with municipal utilities may want to use their public benefit fundstowards street and shade tree projects. With the assistance of the SacramentoTree Foundation, the Sacramento Municipal Utility District’s (SMUD)Sacramento Shade program has planted over 250,000 trees in the Sacramentoregion. SMUD began its program in 1990 and hopes to plant 10,000 trees in1999. SMUD’s overall goal is to plant 500,000 trees.Since October 1992, City of Anaheim Public Utilities’ TreePower Programhas provided free shade trees to residents, businesses and schools. The City'sNeighborhood Services, Code Enforcement and Community PolicingDepartments help to expand the reach of the program into individual neighborhoods. Through TreePower, the City of Anaheim has planted over 10,000trees.vLocal Government ContactsShade Trees in New DevelopmentCity of ReddingPhil Carr, Associate PlannerPlanning Division760 Parkview AvenueRedding, CA 96049-6071 (530) 225-4020City of EscalonJ.D. Hightower, City PlannerP.O. Box 248Escalon, CA 95320 (209) 838-41108Tree Guidelines

AQUA-281Executive SummaryShade Trees in Parking LotsCity of DavisKen Hiatt, Associate PlannerPlanning and Building Department23 Russell Blvd.Davis, CA 95616 (530) 757-5610e-mail: KHiatt@mail.city.davis.ca.us(see also City of Redding)Landscaping Ordinance to Encourage Resource EfficiencyCity of IrvineSteve Burke, Landscape SuperintendentP.O. Box 19575Irvine, CA 92623-9575 (949) 724-7609Collaboratation with Local Community Groups andTree OrganizationsCity of Long BeachCraig Beck, Community Development AnalystCommunity Development Dept.333 West Ocean Blvd., 3rd FloorLong Beach, CA 90802 (562) 570-6866California ReLeafc/o Trust for Public LandStephanie Alting-Mees, Program Manager116 New Montgomery, 3rd floorSan Francisco, CA 94105e-mail: Stephanie Alting Mees attpl-sf@mail.tpl.orgCity of Anaheim Public UtilitiesTreePowerP.O. Box 3222Anaheim, CA 92803 (714) 491-8733Sacramento Municipal Utility District (SMUD)Energy Services Department (916) 455-2020web: www.smud.orgTree Guidelines9

AQUA-281IntroductionIntroductionSan Joaquin Valley communities will be among the fastest growing in thestate during the next decade. The role of urban forests to enhance theenvironment, increase community attractiveness, and foster civic pridewill take on greater significance as Valley communities strive to preserve andimprove their quality of life. Urban and community forestry has been recognized as a cost effective means to cool urban heat islands, improve airquality, and combat global warming.1. Tree planting and stewardship programs provideopportunities for local residents to work together tobuild better communities.San Joaquin Valley communities can promote energy efficiency through tree planting and stewardshipprograms that strategically locate trees to shadebuildings, cool urban heat islands, and minimizeconflicts with power lines and other infrastructureelements. Also, these same trees can also reduceatmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2), improve airquality, reduce stormwater runoff, increase property values, enhance community attractiveness, andpromote public health. Neighborhood tree plantings and stewardship projects stimulate investmentby local citizens, business, and government toimprove their communities. The simple act ofplanting trees also provides opportunities to connect residents with natureand with each other.This report addresses a number of questions about the energy conservationpotential and other benefits of urban and community forests in the SanJoaquin Valley. What is their potential to improve environmental quality andconserve energy? Where should residential and public trees be placed tomaximize their cost-effectiveness? Which tree species will minimize conflictswith power lines, sidewalks, and buildings? What are important features ofsuccessful shade tree programs? What sources of funding and technicalassistance are available?Answers to these questions should assist policy makers, utility personnel,urban forest managers, non-profit organizations, design and planning professionals, and concerned citizens who are planting and managing trees toimprove their local environments and build better communities.10Tree Guidelines

AQUA-281Chapter 11. Identifying Benefits and Costs ofUrban and Community ForestsBenefitsvEnergy Conservation PotentialBuildings and paving increase the ambient temperatures within a city.Rapid growth of California cities during the past 50 years is associatedwith a steady increase in downtown temperatures of about 0.7 F (0.4 C) perdecade. Because electric demand of cities increases about 1 to 2% per F(3-4% per C) increase in temperature, approximately 3-8% of current electricdemand for cooling is used to compensate for this urban heat island effect(Akbari et al. 1992). Warmer temperature in cities compared to surroundingrural areas has other implications, such as increases in carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel power plants, municipal water demand, unhealthyozone levels, and human discomfort and disease. These problems are accentuated by global climate change, which may double the rate of urban warming. Accelerating urbanization, especially in the San Joaquin Valley, hastensthe need for energy-efficient landscapes.Urban forests modify climate and conserve building ene

vTranspiring water and shading surfaces, which lowers local air temper-atures, thereby reducing ozone levels. Trees can emit various biogenic volatile organic compounds that can con-tribute to ozone formation. The ozone forming potential of different tree species varies con