Transcription

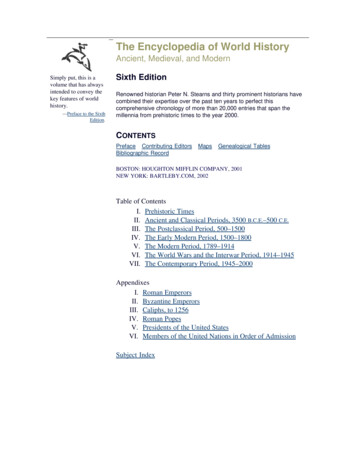

The Encyclopedia of World HistoryAncient, Medieval, and ModernSimply put, this is avolume that has alwaysintended to convey thekey features of worldhistory.—Preface to the SixthEdition.Sixth EditionRenowned historian Peter N. Stearns and thirty prominent historians havecombined their expertise over the past ten years to perfect thiscomprehensive chronology of more than 20,000 entries that span themillennia from prehistoric times to the year 2000.CONTENTSPreface Contributing EditorsBibliographic RecordMapsGenealogical TablesBOSTON: HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY, 2001NEW YORK: BARTLEBY.COM, 2002Table of ContentsI. Prehistoric TimesII. Ancient and Classical Periods, 3500 B.C.E.–500 C.E.III. The Postclassical Period, 500–1500IV. The Early Modern Period, 1500–1800V. The Modern Period, 1789–1914VI. The World Wars and the Interwar Period, 1914–1945VII. The Contemporary Period, 1945–2000AppendixesI. Roman EmperorsII. Byzantine EmperorsIII. Caliphs, to 1256IV. Roman PopesV. Presidents of the United StatesVI. Members of the United Nations in Order of AdmissionSubject Index

NEXTCONTENTS · SUBJECT INDEX · BIBLIOGRAPHIC RECORDThe Encyclopedia of World History. 2001.Table of ContentsPage 1I. Prehistoric TimesA. Introduction1. History and Prehistory2. The Study of Prehistorya. Archaeology as Anthropology and Historyb. Culture and Contextc. Time and Spaced. Finding and Digging up the Paste. Analysis and Interpretationf. Subdividing Prehistoric Timesg. Theoretical Approaches to PrehistoryB. Prehistory and the Great Ice AgeC. Human Origins (4 Million to 1.8 Million Years Ago)D. Homo Erectus and the First Peopling of the World (1.8 Million to 250,000 Years Ago)1. Homo Erectus2. Fire3. Out of AfricaE. Early Homo Sapiens (c. 250,000 to c. 35,000 Years Ago)1. The NeanderthalsF. The Origins of Modern Humans (c. 150,000 to 100,000 Years Ago)G. The Spread of Modern Humans in the Old World (100,000 to 12,000 Years Ago)1. Europe2. Eurasia and Siberia3. South and Southeast Asia

H. The First Settlement of the Americas (c. 15,000 Years Ago)I. After the Ice Age: Holocene Hunter-Gatherers (12,000 Years Ago to Modern Times)1. African Hunter-Gatherers2. Asian Hunter-Gatherers3. Mesolithic Hunter-Gatherers in Europe4. Near Eastern Hunters and Foragers5. Paleo-Indian and Archaic North Americans6. Central and South AmericansJ. The Origins of Food ProductionK. Early Food Production in the Old World (c. 10,000 B.C.E. and Later)1. First Farmers in the Near East2. Early European Farmers3. Egypt and Sub-Saharan Africa4. Asian FarmersL. The Origins of Food Production in the Americas (c. 5000 B.C.E. and Later)M. Later Old World Prehistory (3000 B.C.E. and Afterward)1. State-Organized Societies2. Webs of Relations3. Later African Prehistorya. Egypt and Nubiab. West African Statesc. East and Southern Africa4. Europe after 3500 B.C.E.5. Eurasian Nomads6. Asiaa. South Asiab. Chinac. Japand. Southeast Asia7. Offshore Settlement in the PacificN. Chiefdoms and States in the Americas (c. 1500 B.C.E.–1532 C.E.)1. North American Chiefdoms

2. Mesoamerican Civilizationsa. Olmecb. Teotihuacán3. Andean Civilizationsa. Beginningsb. Chavinc. Moched. Tiwanakue. ChimuO. The End of Prehistory (1500 C.E. to Modern Times)The Encyclopedia of World History, Sixth edition. Peter N. Stearns, general editor. Copyright 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company.Maps by Mary Reilly, copyright 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.CONTENTS · SUBJECT INDEX · BIBLIOGRAPHIC RECORDNEXT

I. Prehistoric TimesNEXTCONTENTS · SUBJECT INDEX · BIBLIOGRAPHIC RECORDThe Encyclopedia of World History. 2001.I. Prehistoric TimesA. Introduction1. History and PrehistoryHuman beings have flourished on Earth for at least 2.5 million years. The study of historyin its broadest sense is a record of humanity and its accomplishments from its earliestorigins to modern times. This record of human achievement has reached us in manyforms, as written documents, as oral traditions passed down from generation togeneration, and in the archaeological record—sites, artifacts, food remains, and othersurviving evidence of ancient human behavior. The earliest written records go back about5,000 years in the Near East, in Mesopotamia, and the Nile Valley. Elsewhere, writtenhistory begins much later: in Greece, about 3,500 years ago; in China, about 2,000 yearsago; and in many other parts of the world, after the 15th century C.E. with the arrival ofWestern explorers and missionaries. Oral histories have an even shorter compass,extending back only a few generations or centuries at the most.1History, which remains primarily though not exclusively the study of written documents,covers only a tiny fraction of the human past. Prehistory, the span of human existencebefore the advent of written records, encompasses the remainder of the past 2.5 millionyears. Prehistorians, students of the prehistoric past, rely mainly on archaeologicalevidence to study the origins of humanity, the peopling of the world by humans, and thebeginnings of agriculture and urban civilization.2Archaeology is the study of the human past based on the material remains of humanbehavior. These remains come down to us in many forms. They survive as archaeologicalsites, ranging from the mighty pyramids of Giza built by ancient Egyptian pharaohs toinsignificant scatters of stone tools and animal bones abandoned by very early humans inEast Africa. Then there are caves and rock shelters adorned with ancient paintings andengravings, and human burials that can provide vital information, not only on biologicalmakeup but also on ancient diet and disease and social rankings.3Modern scientific archaeology has three primary objectives: to study the basic culturehistory of prehistoric times, to reconstruct ancient lifeways, and to study the processes bywhich human cultures and societies changed over long periods of time. Archaeology is4

unique among all scientific disciplines in its ability to chronicle human biological andcultural change over long periods of time. The development of this sophisticatedapproach to the human past ranks as one of the major scientific achievements of thiscentury.Archaeology, by its very nature, is concerned more with the material and theenvironmental. It is basically an anonymous science, dealing with generalities abouthuman cultures derived from artifacts, buildings, and food remains rather than with theindividuals who appear in many of the historians' archives. But by using complextheoretical models and carefully controlled analogies from living societies, it issometimes possible for the archaeologist to gain insights into prehistoric spiritual andreligious life, and into the great complexities of ancient human societies living in worldsremote from our own.5The Encyclopedia of World History, Sixth edition. Peter N. Stearns, general editor. Copyright 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company.Maps by Mary Reilly, copyright 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.CONTENTS · SUBJECT INDEX · BIBLIOGRAPHIC RECORDNEXT

I. Prehistoric Times A. Introduction 2. The Study of PrehistoryPREVIOUSNEXTCONTENTS · SUBJECT INDEX · BIBLIOGRAPHIC RECORDThe Encyclopedia of World History. 2001.2. The Study of Prehistorya. Archaeology as Anthropology and HistoryIn contrast to classicists and historians, prehistoric archaeologists deal with an enormoustime scale of human biological and cultural evolution that extends back at least 2.5million years. Prehistoric archaeology is the primary source of information on 99 percentof human history. Prehistoric archaeologists investigate how early human societies allover the world came into being, how they differed from one another, and, in particular,how they changed through time.1No one could possibly become an expert in all periods of human prehistory. Somespecialists deal with the earliest human beings, working closely with geologists andanthropologists concerned with human biological evolution. Others are experts on stonetoolmaking, the early peopling of the New and Old Worlds, or on many other topics, suchas the origins of agriculture in the Near East. All of this specialist expertise means thatarchaeologists, whatever time period they are working on, draw on scientists from manyother disciplines—botanists, geologists, physicists, zoologists.2Prehistoric archaeologists consider themselves a special type of anthropologist.Anthropologists study humanity in the widest possible sense, and archaeologicalanthropologists study human societies of the past that are no longer in existence. Theirultimate research objectives are the same as those of anthropologists studying livingsocieties. Instead of using informants, however, they use the material remains of longvanished societies to reach the same general goals. Prehistorians also share manyobjectives with historians, but work with artifacts and food remains rather thandocuments. In some parts of the world, such as tropical Africa, for example, prehistoricarchaeology is the primary way of writing history, since oral traditions extend back only afew centuries, and in many places written records appear no earlier than the 19th century3C.E.

The Encyclopedia of World History, Sixth edition. Peter N. Stearns, general editor. Copyright 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company.Maps by Mary Reilly, copyright 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.CONTENTS · SUBJECT INDEX · BIBLIOGRAPHIC RECORDPREVIOUSNEXT

I. Prehistoric Times A. Introduction 2. The Study of Prehistory b. Culture and ContextPREVIOUSNEXTCONTENTS · SUBJECT INDEX · BIBLIOGRAPHIC RECORDThe Encyclopedia of World History. 2001.b. Culture and ContextAnthropology, and archaeology as part of it, is unified by one common thread, theconcept of culture. Everyone lives within a cultural context—middle-class Americans,Romans, and Kwakiutl Indians of northwestern North America. Each culture has its ownrecognizable cultural style, which shapes the behavior of its members, their political andjudicial institutions, and their morals.1Human culture is unique because much of its content is transmitted from generation togeneration by sophisticated communication systems. Formal education, religious beliefs,and daily social intercourse all transmit culture and allow societies to develop complexand continuing adaptations to aid their survival. Culture is a potential guide to humanbehavior created through generations of human experience. Human beings are the onlyanimals that use culture as their primary means of adapting to the environment. Whilebiological evolution has protected animals like the arctic fox from bitterly cold winters,only human beings make thick clothes in cold latitudes and construct light thatchedshelters in the Tropics.2Culture is an adaptive system, an interface between ourselves, the environment, and otherhuman societies. Throughout the long millennia of prehistory, human culture becamemore elaborate, for it is our only means of adaptation and we are always adjusting toenvironmental, technological, and societal change.3The great Victorian anthropologist Sir Edward Tylor described culture as “that complexwhole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any othercapabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.” Prehistoricarchaeologists prefer to define culture as the primary nonbiological means by whichpeople adapt to their environment. They consider it as representing the cumulativeintellectual resources of human societies, passed down by the spoken word and byexample.4Human cultures are made up of many different parts, such as language, technology,religious beliefs, ways of obtaining food, and so on. These elements interact with oneanother to form complex and ever-changing cultural systems, systems that adjust to longand short-term environmental change.5

Archaeologists work with the tangible remains of ancient cultural systems, typically suchdurable artifacts as stone tools or clay pot fragments. Such finds are a patterned reflectionof the culture that created them. Archaeologists spend much time studying the linkagesbetween past cultures and their archaeological remains. They do so within precisecontexts of time and space.6The Encyclopedia of World History, Sixth edition. Peter N. Stearns, general editor. Copyright 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company.Maps by Mary Reilly, copyright 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.CONTENTS · SUBJECT INDEX · BIBLIOGRAPHIC RECORDPREVIOUSNEXT

I. Prehistoric Times A. Introduction 2. The Study of Prehistory c. Time and SpacePREVIOUSNEXTCONTENTS · SUBJECT INDEX · BIBLIOGRAPHIC RECORDThe Encyclopedia of World History. 2001.c. Time and SpaceArchaeologists date the past and study the ever-changing distributions of ancient culturesacross the world by studying the context of archaeological finds, whether sites, foodremains, or artifacts, in time and space. This is the study of culture history, thedescription of human cultures as they extend back thousands of years.11. TimeHuman prehistory has a time scale of more than 2.5 million years and a vast landscape ofarchaeological sites that were occupied for long and short periods of time. Some, like theAztec capital, Tenochtitlán, in the Valley of Mexico, were occupied for a few centuries.Others, like Olduvai Gorge in East Africa, were visited repeatedly over hundreds ofthousands of years. The chronology of prehistory is made up from thousands of carefulexcavations and many types of dating tests. These have created hundreds of localsequences of prehistoric cultures and archaeological sites throughout the world.2Historical records provide a chronology for about 5,000 years of human history in Egyptand Mesopotamia, less time in other regions. For earlier times, archaeologists rely onboth relative and absolute dating methods to develop chronological sequences.3Relative dating is based on a fundamental principle of stratigraphic geology, the Law ofSuperposition, which states that underlying levels are earlier than those that cover them.Thus any object found in a lower level is from an earlier time than any from upper layers.Manufactured artifacts are the fundamental data that archaeologists use to study humanbehavior. These artifacts have changed in radical ways with passing time. One has only tolook at the simple stone choppers and flakes made by the first humans and compare themwith the latest luxury automobile to get the point. By combining the study of changes inartifact forms with observations of their contexts in stratified layers in archaeologicalsites, the prehistorian can develop relative chronologies for artifacts, sites, and cultures inany part of the world.4The story of prehistory has unfolded against a backdrop of massive world climatic change5

during the Great Ice Age (See Prehistory and the Great Ice Age). Sometimes, whenhuman artifacts come to light in geological strata dating to the Ice Age, one can placethem in a much broader geological context. But in such cases, as with relativechronologies from other archaeological sites, determining the actual date of these sitesand artifacts in years is a matter of guesswork, or of applying absolute dating methods.Absolute chronology is the process of dating in calendar years. A whole battery ofchronological methods have been developed to date human prehistory, some of themfrankly experimental, others well established and widely used. The following are the bestknown ones.6a. Historical Records and Objects of Known AgeHistorical documents can sometimes be used to date events, such as the death of anancient Egyptian pharaoh or the Spanish conquest of Mexico in 1519–21 C.E. Clay tabletrecords in Mesopotamia and ancient Egyptian papyri provide dates going back to about3000 B.C.E. The early Near Eastern civilizations traded many of their wares, such aspottery or coins with precise dates, over long distances. These objects can be used to datesites in, say, temperate Europe, far from literate civilization at the time.7The Encyclopedia of World History, Sixth edition. Peter N. Stearns, general editor. Copyright 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company.Maps by Mary Reilly, copyright 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.CONTENTS · SUBJECT INDEX · BIBLIOGRAPHIC RECORDPREVIOUSNEXT

I. Prehistoric Times A. Introduction 2. The Study of Prehistory d. Finding and Digging up the PastPREVIOUSNEXTCONTENTS · SUBJECT INDEX · BIBLIOGRAPHIC RECORDThe Encyclopedia of World History. 2001.d. Finding and Digging up the PastThe finding and excavating of archaeological sites is a meticulous process of uncoveringand recording the finite archives that make up the archaeological record. The sites, largeand small, that make up this record are finite resources. Once destroyed and the contextof their artifact contents disturbed, they are gone forever.1Although the destruction wrought by early archaeologists and treasure hunters wasdevastating, that of modern industrial development, deep plowing, professional looters,and amateur pothunters has been far worse. In some parts of North America, expertsestimate that less than 5 percent of the archaeological record of prehistoric times remainsintact. In recent years, massive efforts have been made to stem the tide of destruction andto preserve important sites using federal and state laws and regulations. While someprogress has been made in such cultural resource management, the recentarchaeological record of human prehistory is a shadow of its former self and in manyparts of the world is doomed to near-total destruction.21. Finding Archaeological SitesMany archaeological sites come to light by accident: during highway or damconstruction, through industrial activity and mining, or as a result of natural phenomenasuch as wind erosion. For example, the famous early human sites at Olduvai Gorge inTanzania, East Africa, were exposed in the walls of the gorge as a result of an ancientearthquake that cut a giant fissure through the surrounding plains. Well-designedarchaeological field surveys provide vital information on ancient settlement patterns andsite distributions.3Increasingly, archaeologists are relying on remote sensing techniques, such as aerialphotography, satellite imagery (digital images of the earth recorded by satellites), or sidescan radar (airplane-based radar used to penetrate ground cover). These allow them toidentify likely areas, even to spot sites without ever going into the field. The latestapproach involves the use of Geographic Information Systems (mapping systems basedon satellite imagery that inventory environmental data). The combination of satellite4

imagery with myriad environmental, climatic, and other data provides a backdrop forinterpreting distributions of archaeological sites. For instance, in Arkansas, archaeologistshave been able to study the locations of river valley farming villages and establish thatthey were founded close to easy routes to the uplands, where deer could be hunted inwinter.The Encyclopedia of World History, Sixth edition. Peter N. Stearns, general editor. Copyright 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company.Maps by Mary Reilly, copyright 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.CONTENTS · SUBJECT INDEX · BIBLIOGRAPHIC RECORDPREVIOUSNEXT

I. Prehistoric Times A. Introduction 2. The Study of Prehistory e. Analysis and InterpretationPREVIOUSNEXTCONTENTS · SUBJECT INDEX · BIBLIOGRAPHIC RECORDThe Encyclopedia of World History. 2001.e. Analysis and InterpretationFor every month of excavation there is at least six months' laboratory analysis—a longprocess of classifying, analyzing, and interpreting the finds from the dig. Such finds comein many forms. Stone tools, clay potsherds, and other artifacts tell us much about thetechnology of our forebears. Broken animal bones, seeds, shells, and other food remains,even desiccated human feces, are a mine of information on ancient subsistence, andsometimes diet. All of these finds are combined to produce a reconstruction of humanbehavior at the site.11. Analysis of ArtifactsHuman artifacts come in many forms. The most durable are stone tools and clay vessels,while those in wood and bone often perish in the soil. Archaeologists have developedelaborate methods for classifying artifacts of all kinds, classifications based on distinctivefeatures like the shapes of clay vessels, painted decoration on the pot, methods of stoneflaking, and so on. Once they have worked out a classification of artifact types, theexperts use various arbitrary units to help order groups of artifacts in space and time.2These units include the assemblage, which is a diverse group of artifacts found in onesite that reflect the shared activities of a community. Next is the component, a physicallybounded portion of a site that contains a distinct assemblage. The social equivalent of anarchaeologist's component is a community. Obviously a site can contain severalcomponents, stratified one above another. The final unit is the culture, a cultural unitrepresented by like components on different sites or at different levels of the same site,although always within a well-defined chronological bracket.3Archaeological “cultures” are concepts designed to assist in the ordering of artifacts intime and space. They are normally named after a key site where characteristic artifacts ofthe culture are found. For instance, the Acheulian culture of early prehistory is namedafter the northern French town of St. Acheul, where the stone hand axes so characteristicof this culture are found.4

The Encyclopedia of World History, Sixth edition. Peter N. Stearns, general editor. Copyright 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company.Maps by Mary Reilly, copyright 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.CONTENTS · SUBJECT INDEX · BIBLIOGRAPHIC RECORDPREVIOUSNEXT

I. Prehistoric Times A. Introduction 2. The Study of Prehistory f. Subdividing Prehistoric TimesPREVIOUSNEXTCONTENTS · SUBJECT INDEX · BIBLIOGRAPHIC RECORDThe Encyclopedia of World History. 2001.f. Subdividing Prehistoric TimesThe 2.5 million years of human prehistory have seen a brilliant diversity of humansocieties, both simple and complex, flourish at different times throughout the world. Eversince the early 19th century, archaeologists have tried with varying degrees of success tosubdivide prehistory into meaningful general subdivisions.1The most durable subdivisions of the prehistoric past were devised by Danisharchaeologist Christian Jurgensen Thomson in 1806. His Three Age System, based onfinds from prehistoric graves, subdivided prehistory into three ages based ontechnological achievement: the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age. Thisscheme has been proven to have some general validity in the Old World and is still usedas a broad label to this day. However, the term Stone Age has little more thantechnological significance, for it means that a society does not have the use of metals ofany kind. Stone Age has no chronological significance, for although societies withoutmetal vanished in the Near East after 4000 B.C., some still flourish in New Guinea to thisday. We only use the Three Age System in the most general way here.2Sometimes, the three ages are subdivided further. The Stone Age, for example, isconventionally divided into three periods: the Palaeolithic, or Old Stone Age (Greek:from palaios, old; and from lithos, stone), which applies to societies who used chippedstone technology; the Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age), which is a transitional period; andthe Neolithic (New Stone Age), when people used polished stone artifacts and werefarmers. However, only the term Palaeolithic remains in common use, as Mesolithic andNeolithic have proved increasingly meaningless, even if they occasionally appear inspecialist and popular literature.3New World archaeologists have never used the Three Age System, largely because in theAmericas, metallurgy of any kind had limited distribution. They tend to use more localterms, defined at intervals in these pages.4In recent years, archaeologists have tried to classify prehistoric societies on the basis ofpolitical and social development. They subdivide all human societies into two broadcategories: prestate and state-organized societies.5Prestate societies are invariably small-scale, based on the community, band, or village.6

Many prestate societies are bands, associations of families that may not exceed 25 to 60people, the dominant form of social organization for most hunter-gatherers from theearliest times up to the origins of farming. Clusters of bands linked by clans, groups ofpeople linked by common ancestral ties, are labeled tribes. Chiefdoms are societiesheaded by individuals with unusual ritual, political, or entrepreneurial skills, and areoften hard to distinguish from tribes. Such societies are still kin-based, but power isconcentrated in the hands of powerful kin leaders responsible for redistributing food andother commodities through society.Chiefdoms tend to have higher population densities and vary greatly in their elaboration.For example, Tahitian chiefs in the Society Islands of the South Pacific presided overelaborate, constantly bickering chiefdoms, frequently waging war against their neighbors.7State-organized societies operate on a large scale, with a centralized political and socialorganization, distinct social and economic classes, and large food surpluses created byintensive farming, often employing irrigation agriculture. Such complex societies wereruled by a tiny elite class, who held monopolies over strategic resources and used forceand religious power to enforce their authority. Such social organization was typical of theworld's preindustrial civilizations, civilizations that functioned with technologies thatdid not rely on fossil fuels like coal.8The Encyclopedia of World History, Sixth edition. Peter N. Stearns, general editor. Copyright 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company.Maps by Mary Reilly, copyright 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.CONTENTS · SUBJECT INDEX · BIBLIOGRAPHIC RECORDPREVIOUSNEXT

I. Prehistoric Times A. Introduction 2. The Study of Prehistory g. Theoretical Approaches toPrehistoryPREVIOUSNEXTCONTENTS · SUBJECT INDEX · BIBLIOGRAPHIC RECORDThe Encyclopedia of World History. 2001.g. Theoretical Approaches to PrehistoryArchaeologists study human prehistory within broad theoretical frameworks. Suchtheoretical approaches are a means for looking beyond the facts and material objects fromarchaeological sites for explanations of cultural developments and changes that tookplace during the remote past.1Two broad theoretical approaches dominate interpretative thinking:21. Culture HistoryCulture-historical approaches are based on systematic descriptions of sites, artifacts, andentire cultural sequences. Culture history is based on studies of archaeological context intime and space. Such studies are the backbone of all archaeological research and provideus with the chronology of human prehistory. They also give us data on the broaddistributions of human cultures through the Old and the New World over more than 2.5million years. No more sophisticated theoretical approaches can exist without thisculture-historical background.3The Encyclopedia of World History, Sixth edition. Peter N. Stearns, general editor. Copyright 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company.Maps by Mary Reilly, copyright 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.CONTENTS · SUBJECT INDEX · BIBLIOGRAPHIC RECORDPREVIOUSNEXT

I. Prehistoric Times B. Prehistory and the Great Ice AgePREVIOUSNEXTCONTENTS · SUBJECT INDEX · BIBLIOGRAPHIC RECORDThe Encyclopedia of World History. 2001.B. Prehistory and the Great Ice AgeThe biological and cultural evolution of humankind unfolded against a complex backdropof constant climatic change. For most of geological time, the world's climate was warmerand more homogeneous than it is today. The first signs of glacial cooling occurred inAntarctica about 35 million years ago. There was a major drop in world temperaturesbetween 14 and 11 million years ago, and another about 3.2 million years ago, whenglaciers first formed in northern latitudes. Then, just as humans first appeared, about 2.5million years ago, the glaciation intensified and the earth entered its present period ofconstantly fluctuating climate.1Humans evolved during the period of relatively minor climatic oscillations. Between 4and 2 million years ago, the world climate was somewhat warmer and more stable than itbecame in later times. The African savanna, where humans originated, supported manymammal species, large and small, including a great variety of the order Primates, towhich we belong.2About 1.6 million years ago, at the beginning of the Pleistocene (commonly called theGreat Ice Age), the world's climatic changes intensified. Global climates constantlyfluctuated between warm and intensely cold. For long stretches of time, the northern partsof both Europe and North America were mantled with great ice sheets, the last retreatingonly some 15,000 years ago. While glaciers covered northern areas, world sea levels fellas much as 300 feet below modern shorelines, joining Alaska to Siberia, Britain to theContinent, and exposing vast continental shelves off ocean coasts. The glacial periodsbrought drier conditions to tropical regions. The Sahara and northern Africa became veryarid, and rain forests shrunk.3Fluctuations of warm and cold temperatures were relatively minor until about 800

whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.” Prehistoric archaeologists prefer to define culture as the primary nonbiological means by which people adapt to their env