Transcription

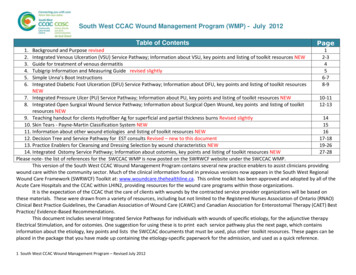

INTERNATIONAL BEST PRACTICEBEST PRACTICEGUIDELINES: WOUNDMANAGEMENT INDIABETIC FOOT ULCERS3 BEST PRACTICE GUIDELINES FOR SKIN AND WOUND CARE IN EPIDERMOLYSIS BULLOSA

FOREWORDSupported by an educationalgrant from B BraunThe views presented in thisdocument are the work of theauthors and do not necessarilyreflect the opinions of B Braun.Published byWounds InternationalA division of SchofieldHealthcare Media LimitedEnterprise House1–2 HatfieldsLondon SE1 9PG, UKwww.woundsinternational.comTo cite this document.International Best PracticeGuidelines: Wound Management in Diabetic Foot Ulcers.Wounds International,2013. Available from: www.woundsinternational.comThis document focuses on wound management best practice for diabeticfoot ulcers (DFUs). It aims to offer specialists and non-specialists everywherea practical, relevant clinical guide to appropriate decision making and effective wound healing in people presenting with a DFU.In recognition of the gap in the literature in the field of wound management, this document concentrates on the importance of wound assessment,debridement and cleansing, recognition and treatment of infection andappropriate dressing selection to achieve optimal healing for patients. However, it acknowledges that healing of the ulcer is only one aspect of management and the role of diabetic control, offloading strategies and an integratedwound care approach to DFU management (which are all covered extensively elsewhere) are also addressed. Prevention of DFUs is not discussed inthis document.The scope of the many local and international guidelines on managing DFUsis limited by the lack of high-quality research. This document aims to gofurther than existing guidance by drawing, in addition, from the wide-rangingexperience of an extensive international panel of expert practitioners. However, it is not intended to represent a consensus, but rather a best practiceguide that can be tailored to the individual needs and limitations of differenthealthcare systems and to suit regional practice.EXPERT WORKING GROUPDevelopment groupPaul Chadwick, Principal Podiatrist, Salford Royal Foundation Trust, UKMichael Edmonds, Professor of Diabetes and Endocrinology, Diabetic Foot Clinic, King's CollegeHospital, London, UKJoanne McCardle, Advanced Clinical and Research Diabetes Podiatrist, NHS Lothian UniversityHospital, Edinburgh, UKDavid Armstrong, Professor of Surgery and Director, Southern Arizona Limb Salvage Alliance (SALSA),University of Arizona College of Medicine, Arizona, USAReview groupJan Apelqvist, Senior Consultant, Department of Endocrinology, Skåne University Hospital, Malmo,SwedenMariam Botros, Director, Diabetic Foot Canada, Canadian Wound Care Association and ClinicalCoordinator, Women's College Wound Healing Clinic, Toronto, CanadaGiacomo Clerici, Chief Diabetic Foot Clinic, IRCC Casa di Cura Multimedica, Milan, ItalyJill Cundell, Lecturer/Practitioner, University of Ulster, Belfast Health and Social Care Trust, NorthernIrelandSolange Ehrler, Functional Rehabilitation Department, IUR Clémenceau (Institut Universitaire deRéadaptation Clémenceau), Strasbourg, FranceMichael Hummel, MD, Diabetes Center Rosenheim & Institute of Diabetes Research, HelmholtzZentrum München, GermanyBenjamin A Lipsky, Emeritus Professor of Medicine, University of Washington, USA; Visiting Professor,Infectious Diseases, University of Geneva, Switzerland; Teaching Associate, University of Oxford andDeputy Director, Graduate Entry Course, University of Oxford Medical School, UKJosé Luis Lázaro Martinez, Full Time Professor, Diabetic Foot Unit, Complutense University, Madrid,SpainRosalyn Thomas, Deputy Head of Podiatry, Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Board,Swansea, WalesSusan Tulley, Senior Podiatrist, Mafraq Hospital, Abu Dhabi, United Arab EmiratesC 3 BEST PRACTICEGUIDELINES:WOUNDMANAGEMENTDIABETIC FOOTBULLOSAULCERSBEST PRACTICEGUIDELINESFOR SKINAND WOUNDCARE ININEPIDERMOLYSIS

INTRODUCTIONIntroductionDFUs are complex, chronic wounds, whichhave a major long-term impact on themorbidity, mortality and quality of patients’lives1,2. Individuals who develop a DFU are atgreater risk of premature death, myocardialinfarction and fatal stroke than those withouta history of DFU3. Unlike other chronicwounds, the development and progression ofa DFU is often complicated by wide-rangingdiabetic changes, such as neuropathy andvascular disease. These, along with thealtered neutrophil function, diminished tissueperfusion and defective protein synthesisthat frequently accompany diabetes, presentpractitioners with specific and unique management challenges1.DFUs are relatively common — in the UK,5–7% of people with diabetes currently haveor have had a DFU4,5. Furthermore, around25% of people with diabetes will develop aDFU during their lifetime6. Globally, around370 million people have diabetes and thisnumber is increasing in every country7. Diabetes UK estimates that by 2030 some 552million people worldwide will have diabetes8.DFUs have a major economic impact. A USstudy in 1999 estimated the average outpatient cost of treating one DFU episode as 28,000 USD over a two–year period9. Average inpatient costs for lower limb complications in 1997 were reported as 16,580 USDfor DFUs, 25,241 USD for toe or toe plusother distal amputations and 31,436 USDfor major amputations10,11.such as the effect on physical, psychologicaland social wellbeing and the fact that manypatients are unable to work long term as aresult of their wounds6.A DFU is a pivotal event in the life of aperson with diabetes and a marker of seriousdisease and comorbidities. Without earlyand optimal intervention, the wound canrapidly deteriorate, leading to amputation ofthe affected limb5,13.It has been estimated that every 20 secondsa lower limb is amputated due to complications of diabetes14.In Europe, the annual amputation rate forpeople with diabetes has been cited as 0.50.8%1,15, and in the US it has been reportedthat around 85% of lower-extremityamputations due to diabetes begin with footulceration16,17.Mortality following amputation increaseswith level of amputation18 and ranges from50–68% at five years, which is comparableor worse than for most malignancies13,19(Figure 1).The statistics need not make for such grimreading. With appropriate and carefulmanagement it is possible to delay or avoidmost serious complications of DFUs1.FIGURE 1: Relative five-year mortality (%) (adapted opathiphomncerlymcaHodgkin'ssttecaBreataProsIn England, foot complications account for20% of the total National Health Servicespend on diabetes care, which equates toaround 650 million per year (or 1 in every 150)5. Of course, these figures do not takeaccount of the indirect costs to patients,ncerThe EURODIALE study examined total directand indirect costs for one year across severalEuropean countries. Average total costsbased on 821 patients were approximately10,000 euros, with hospitalisation representing the highest direct cost. Based on prevalence data for Europe, they estimated thatcosts associated with treatment of DFUsmay be as high as 10 billion euros per year12.BEST PRACTICE GUIDELINES: WOUND MANAGEMENT IN DIABETIC FOOT ULCERS1

INTRODUCTIONIt has been suggested that up to 85% ofamputations can be avoided when an effective care plan is adopted20. Unfortunately,insufficient training, suboptimal assessmentand treatment methods, failure to referpatients appropriately and poor access to specialist footcare teams hinder the prospects ofachieving optimal outcomes21,22.Successful diagnosis and treatment ofpatients with DFUs involves a holisticapproach that includes:Q Optimal diabetes controlQ Effective local wound careQ Infection controlQ Pressure relieving strategiesQ Restoring pulsatile blood flow.Many studies have shown that planned intervention aimed at healing of DFUs is mosteffective in the context of a multidisciplinaryteam with the patient at the centre of thiscare.One of the key tenets underpinning thisdocument is that infection is a major threatto DFUs — much more so than to wounds2 3 of other aetiologies not subject to diabeticchanges. A European-wide study found that58% of patients attending a foot clinic with anew ulcer had a clinically infected wound23.Similarly a single-centre US study found thatabout 56% of DFUs were clinically infected24.This study also showed the risk of hospitalisation and lower-extremity amputation to be56–155 times greater for diabetes patientswith a foot infection than those without24.Recognising the importance of starting treatment early may allow practitioners to preventprogression to severe and limb-threateninginfection and potentially halt the inevitablepathway to amputation25.This document offers a global wound careplan for practitioners (page 20), whichincludes a series of steps for preventingcomplications through active management— namely prompt and appropriate treatmentof infection, referral to a vascular specialist tomanage ischaemia and optimal wound care.This should be combined with appropriatepatient education and an integrated approachto care.BEST PRACTICEGUIDELINES:WOUNDMANAGEMENTDIABETIC FOOTBULLOSAULCERSBEST PRACTICEGUIDELINESFOR SKINAND WOUNDCARE ININEPIDERMOLYSIS

AETIOLOGY OFDFUsAetiology of DFUsThe underlying cause(s) of DFUs will have a significant bearing on the clinicalmanagement and must be determined before a care plan is put into placeIn most patients, peripheral neuropathy andperipheral arterial disease (PAD) (or both)play a central role and DFUs are thereforecommonly classified as (Table 1)26:Q NeuropathicQ IschaemicQ Neuroischaemic (Figures 2–4).Neuroischaemia is the combined effectof diabetic neuropathy and ischaemia,whereby macrovascular disease and, insome instances, microvascular dysfunctionimpair perfusion in a diabetic foot26,27.PERIPHERAL NEUROPATHYPeripheral neuropathy may predispose thefoot to ulceration through its effects on thesensory, motor and autonomic nerves:Q The loss of protective sensation experienced by patients with sensory neuropathyrenders them vulnerable to physical,chemical and thermal traumaQ Motor neuropathy can cause footdeformities (such as hammer toes andclaw foot), which may result in abnormalpressures over bony prominencesQ Autonomic neuropathy is typicallyassociated with dry skin, which can resultin fissures, cracking and callus. Anotherfeature is bounding pulses, which isoften misinterpreted as indicating a goodcirculation28.Loss of protective sensation is a majorcomponent of nearly all DFUs29,30. It is associated with a seven–fold increase in riskof ulceration6.Patients with a loss of sensation will havedecreased awareness of pain and othersymptoms of ulceration and infection31.is increasing and it is reported to be a contributory factor in the development of DFUsin up to 50% of patients14,28,33.It is important to remember that even in theabsence of a poor arterial supply, microangiopathy (small vessel dysfunction)contributes to poor ulcer healing in neuroischaemic DFUs34. Decreased perfusion inthe diabetic foot is a complex scenario andis characterised by various factors relatingto microvascular dysfunction in addition toPAD34.DFUs usually result from two or more riskfactors occurring together. Intrinsic elementssuch as neuropathy, PAD and foot deformity (resulting, for example, from neuropathicstructural changes), accompanied by anexternal trauma such as poorly fitting footwear or an injury to the foot can, over time,lead to a DFU7.FIGURE 3: Ischaemic DFUFIGURE 4: NeuroischaemicDFUTABLE 1: Typical features of DFUs according to SensationSensory lossPainfulDegree of sensorylossCallus/necrosisCallus present andoften thickNecrosis commonMinimal callusProne to necrosisWound bedPink and granulating, surrounded bycallusPale and sloughywith poorgranulationPoor granulationFoot temperatureand pulsesWarm with bounding pulsesCool with absentpulsesCool with absentpulsesOtherDry skin andfissuringDelayed healingHigh risk ofinfectionTypical locationWeight-bearingareas of the foot,such as metatarsalheads, the heel andover the dorsum ofclawed toesTips of toes, nailedges and betweenthe toes and lateralborders of the footMargins of thefoot and toesPrevalence(based on35)35%15%50%PERIPHERAL ARTERIAL DISEASEPeople with diabetes are twice as likely tohave PAD as those without diabetes32. Itis also a key risk factor for lower extremityamputation30. The proportion of patientswith an ischaemic component to their DFUFIGURE 2: Neuropathic DFUBEST PRACTICE GUIDELINES: WOUND MANAGEMENT IN DIABETIC FOOT ULCERS3

ASSESSING DFUsAssessing DFUsPatients with a DFU need to be assessed holistically and intrinsic and extrinsicfactors consideredFor the non-specialist practitioner, the key skillrequired is knowing when and how to refer apatient with a DFU to the multidisciplinary footcare team (MDFT; see page 19). Patients witha DFU should be assessed by the team withinone working day of presentation — or soonerin the presence of severe infection22,36,37. Inmany places, however, MDFTs do not exist andpractitioners instead work as individuals. Inthese situations, the patient’s prognosis oftendepends on a particular practitioner’s knowledge and interest in the diabetic foot.Patients with a DFU need to be assessed holistically to identify intrinsic and extrinsic factors.This should encompass a full patient historyincluding medication, comorbidities and diabetes status38. It should also take into consideration the history of the wound, previous DFUs oramputations and any symptoms suggestive ofneuropathy or PAD28.EXAMINATION OF THE ULCERA physical examination should determine:Q Is the wound predominantly neuropathic,ischaemic or neuroischaemic?Q If ischaemic, is there critical limb ischaemia?Q Are there any musculoskeletal deformities?Q What is the size/depth/locati

People with diabetes are twice as likely to have PAD as those without diabetes32. It is also a key risk factor for lower extremity amputation30. The proportion of patients with an ischaemic component to their DFU is increasing and it is reported to be a con-tributory factor in the development of DFUs in up to 50% of patients14,28,33.