Transcription

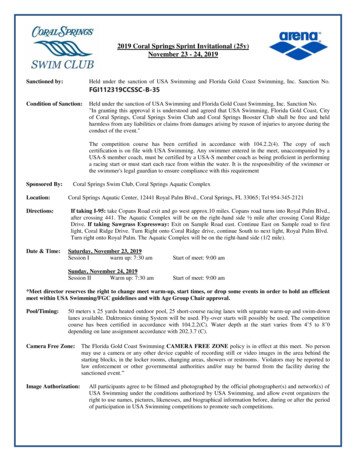

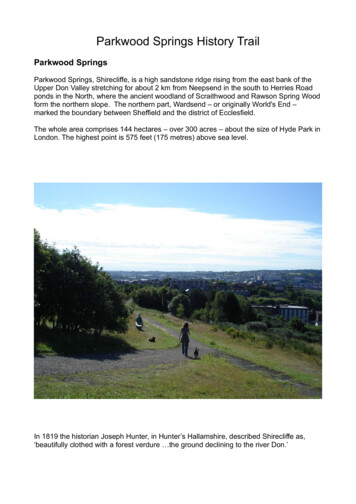

Parkwood Springs History TrailParkwood SpringsParkwood Springs, Shirecliffe, is a high sandstone ridge rising from the east bank of theUpper Don Valley stretching for about 2 km from Neepsend in the south to Herries Roadponds in the North, where the ancient woodland of Scraithwood and Rawson Spring Woodform the northern slope. The northern part, Wardsend – or originally World's End –marked the boundary between Sheffield and the district of Ecclesfield.The whole area comprises 144 hectares – over 300 acres – about the size of Hyde Park inLondon. The highest point is 575 feet (175 metres) above sea level.In 1819 the historian Joseph Hunter, in Hunter’s Hallamshire, described Shirecliffe as,‘beautifully clothed with a forest verdure the ground declining to the river Don.’

For centuries the hillside was wooded, with sandstone outcrops which give the name‘Shirecliffe’, which means bright or gleaming, steep hillside. Certainly the ridge catches theafternoon and evening sun and the sandstone outcrops – mainly Grenoside sandstone must have shone brightly. There are two SSSIs (sites of special scientific interest) whereoutcrops of Carboniferous sandstone are found - formed c. 300 million years ago whenSheffield had a tropical climate!The site of one SSSI – theold Neepsend brickworkswhere some Neolithicremains were lost throughquarrying for ganister toline the furnaces of thesteel works.The views from Parkwood Springs over the city - through the Rivelin and Loxley valleysout to Derwent Edge - are stunning and not to be missed, particularly at sunset when thehillsides and valleys of Sheffield City acquire a magical, misty red glow.The Beaconsevent eachOctober –sunsetfrom theviewpoint.

From Parkwood Springsthere are panoramic viewsover the City of Sheffield.Local Councillor and former LordMayor, Jackie Drayton, surveying cityviews from a sandstone outcrop.Over the centuries Parkwood Springs has undergone a varied history of humanintervention - used for hunting grounds, mining, woodland management, coppicing andtree clearing, quarrying, farming, industrialisation, industrial settlement, railway and powerstation, a cemetery, allotments, military use, landfill, the ski village, industrial andrecreational facilities.The majority of the land is in the ownership of Sheffield City Council, which also assumedresponsibility for Wardsend Cemetery from the Church of England. Viridor Ltd. continue toown the restored landfill site and will continue to be responsible for its maintainance.

The Ski VillageFor more than 20 years the ski slopes provideda valuable asset to the city. Many schoolgroups used the facilities.Fires at the ski village left the area needingurgent work to secure and redevelop the site.Redevelopment plans are finally underway.The Mountain Bike Trail was installed in 2012 attracting mountain bikers from across thecountry as well as offering local people a world-class biking facility free of charge andclose to the city centre.Our Country Park in the City.For about 30 years from the 1970s, Parkwood Springs was left neglected and largelyforgotten - known mainly as a site for landfill and the recycling of refuse. During this time,however, nature began to reclaim and re-vegetate the area. Parkwood Springs began toregenerate as a place of wild heath and woodland offering the natural beauty of a potentialcountry park within a mile of Sheffield City Centre.

In 2002, the City Council launched the initiative: Parkwood Springs – Your Vision.Community consultation and involvement led to setting up the Friends of ParkwoodSprings in 2010 supporting a wide range of activities and developments to bring ParkwoodSprings into responsible public use. Visitors can enjoy the wild, open space and steepescarpments for recreation and sport, observe and study wildlife and help to conserve abeautiful landscape for quiet reflection and renewal - all within a short distance of highdensity housing and the city centre. Parkwood Springs brings a history which reflects rural,industrial and ecological changes over the centuries. It has a unique place in Sheffield'shistorical landscape and will provide a valued city landscape for generations ofSheffielders to enjoy.Beacons 2012Mr. Fox dance with fire.Schools cross country – organised byWatercliffe Meadow.Admiring the view:History walk with the RangersOne of Jason Thomson's sculptures – The Spirit of Parkwood at the Gateway to ParkwoodSprings at Shirecliffe/Cooks Wood Road.

History Walk – a walk of about 1 hour.Our History walk begins at the sculpture and meeting point – 'The Spirit of Parkwood'.This can be found at the main car park entrance to Parkwood Springs at the junction of Shirecliffe Lane,Shirecliffe Road and Cooks Wood Road. There is a bus stop close by named 'Batworth Road', a bus stopbeside the Sheffield United Academy on Shirecliffe Road, or a short walk from Pitsmoor Post Office whichcan be accessed by a number of bus routes. The car park at this entrance is open at weekends.The walk takes you between key points of interest and is a round walk, therefore you can join it at any pointen route. Just find your starting point and follow from one key point to the next.Point 1The Spirit of Parkwood. (Picture on previous page)The sculpture.The sculpture, The Spirit of Parkwood, was created by Jason Thomson, funded by Viridor Credits LandfillCommunities Fund and Sheffield City Council and installed in December 2011. The sculpture is cast in iron,which has rusted to a warm golden- brown colour. The coating of rust protects the iron structure and remainsdurable in all weathers.In discussion with members of the local community the sculpture was created to encapsulate elements of thehistory and nature of Parkwood Springs. Each element is identified on the explanatory plaque installed closeto the sculpture.Key elements seen in the sculpture include:The deer park, the tree branches giving shape to the charcoal burner’s hut, the stained glass window of theancient chapel, tools of the woodland coppice workers, artefacts from domestic life - both high status andworking people’s lives at Parkwood Springs. Look for the tea pot and the small ball.The intricate interweaving of the ironwork affords a glimpse through history to the landscape beyondPoint 2 - Shirecliffe HallOn the site of the car park stood the ‘new’ Shirecliffe Hall built in the early 1800s by H.E.Watson JP.The Watson family had lived at Shirecliffe Hall since 1775. H.E. Watson had the old Shirecliffe Halldemolished and he built ‘a good modern house near the site’. He was a local dignitary ‘who worthily upholdsthe historic character of his mansion.’ Mr. Watson was ‘chairman of the Borough Conservative andConstitutional Association, Justice of the Peace for the West Riding (Sheffield was in the West Riding at thattime), a Town Trustee, a Church Burgess, a director of Chas. Cammell and Co. Ltd (later Cammell Laird) andto put it shortly, one of the most prominent and popular of local gentlemen.’Nearby, across the top of the present Cooks Wood Road was the site of the old Shirecliffe Hall, which wassituated on Shirecliffe Lane. Shirecliffe Lane ran from Pitsmoor to the present Shirecliffe Road and continuedto approximately the site of the Sheffield United Football Academy, where it became Cockshutt Lane, whichran through Roe Wood.Old ‘Shiercliffe Hall’ – ‘Shirtcliffe Hall Farm’Old Shirecliffe Hall was built by the Norman family - de Mounteney - who gave their name to the Monteneyestate, part of Parson Cross. The family lived at Cowley Manor, Chapeltown, a large castellated manorhouse. They worshipped and were buried at St. Mary’s Church in Ecclesfield where a portrait, thought to beof Joan de Mounteney (1321-1395), still survives in a window.Shirecliffe was a sub-manor gifted to the de Mounteneys after the Norman conquest in 1066 by the deLouvetots, to whom they were related.

In 1392, Sir Thomas de Mounteney was granted a licence by King Richard II to make a deer park atShirecliffe. This was an area for keeping deer as a source of food, hunting game and rabbits and grazinganimals. Shirecliffe Hall was a mediaeval hall or hunting lodge within the deer park.According to Hunter’s Hallamshire, ‘Sir John Mounteney had a license from the Crown to inclose 200 acresof land, 300 acres of wood and 20 acres of his demesne land in Shiercliffe, and to make a park of the same.’‘The family continued to reside at Shiercliffe and Cowley till the reign of King Henry VIII, when the eldest lineended in female heiresses. The last de Mounteney to reside at Shiercliffe was John who died in 1536. Hedied in the prime of life, and there was a tradition that he was assaulted and wounded in the church porch ofSheffield, which wound hastened his death.’In 1568 the property was purchased by John Thwaites, ( brother of John de Mounteney’s son-in –law,Thomas Thwaites.) In 1572, he sold it as a ‘very valuable acquisition’ to George, the 6 th Earl of Shrewbury,who returned it to the manor of Sheffield.In 1587 the de Mounteney heirs contested the sale and regained the property and land at a hearing in York,leasing it to tenant occupants, the Brough family.By the end of the 16th Century the land was ‘disparked’ and turned into large coppiced woods.In 1637 there were still deer in the area. Harrison’s survey details the use of timber and wood. The mapshows Shirtcliffe Hall, Cooke Wood, Oaken Banke Wood, The Lords Wood, Shirtcliffe Parke Wood andScraith Banke. The Hall was tenanted by Richard Burrowes or Boroughs (Brough), ‘gentleman’ and it wasdescribed as ‘ a dwelling house and ancient Chappell, one Barne, one Oxhouse, one Orchard.’In 1638, the lease expired and Mr. Rowland Hancock became the tenant. He was a former vicar ofEcclesfield church, but he was banished to Penistone under the Act of Uniformity. In 1672, when ‘the severityof statutes were a little relaxed’, he returned to Shirecliffe and preached there ‘as the circumstances of thetimes would allow.’ He gathered a few of his neighbours forming a ‘small church on the independent model’,but after his death in 1685 the congregation left to join churches ‘at Attercliffe and Sheffield’.‘Rowland Hancock, tenant of Shirecliffe Hall during the reign of Charles II, was vicar of Ecclesfield and from1661 an assistant minister at the parish church in Sheffield. But neither he, the minister or the other twoassistant ministers were prepared to agree with the requirements of the 1662 Act of Uniformity, so theyresigned their preferments.’‘The 1662 Act of Uniformity led to the expulsion of 2000 clergy from their livings, includingHancock. Hunter says that Hancock "continued to reside in the neighbourhood of Sheffield" untilthe 1665 Five Mile Act required clergy to not come within five miles of incorporated towns or theirformer livings. Hancock was "taken" at Allerthorp near Wakefield in 1668 by Mr Copley of Batleyand sent to York Castle, it's not stated how long he was there. In 1672 there was the RoyalDeclaration of Indulgence which repealed the penal provisions of the previous Acts. Hunter saysthat Hancock then "returned to his own house at Shiercliffe-hall".‘Hancock continued to live in Sheffield until a later Act required non-conformist ministers to move at least fivemiles away from where they formerly preached. He was taken in by Sylvanus Rich of Penistone and livedwith him until the Act was relaxed in 1672. When he was able to return to Shirecliffe, though in 1668 he hadbeen imprisioned in York Castle. In 1676 he and Matthew Bloome of Attercliffe, another former assistantminister, set up a non-conformist "Church of Christ" meeting at Shirecliffe Hall. Twenty people signed theaccount of the rules of the church and a further 34 joined immediately afterwards. Unfortunately Hancockand Bloome had a disagreement after a short time and the church split, some following Bloome to Attercliffe,others remaining with Hancock. Rowland Hancock died at Shirecliffe Hall in 1685 and was buried in theparish church graveyard. He was described as "a very pious man, of excellent natural parts, and tolerablelearning, though he had not been bred at the University." Rowland Hancock had no son, but one of hisdaughters continued to live at Shirecliffe Hall and married Joseph Banks, an influential lawyer who became amember of parliament and was great grandfather of the famous Sir Joseph Banks, president of the RoyalSociety.’Mr. Hancock’s daughter Mary married Joseph Banks, a Sheffield lawyer, and they lived at Shirecliffe Hall untilabout 1700, before retiring to Scofton, near Worksop.

In 1675 permission was granted for hunting the deer in the park. At this time there was also evidence ofcharcoal burning in the area.Through the 18th century Old Shirecliffe Hall was let to a succession of tenants until it came into thepossession of the Watson family in 1775, who completely rebuilt it as the ‘new’ Shirecliffe Hall by about 1803.Much of the stone from the old hall appears to have been used locally - there are many walls around thearea built from very old and weathered sandstone – we may guess where it came from.Other buildings on Shirecliffe Lane may have been associated with Shirecliffe Hall including Shirecliffe Grovewhich is detailed on one map as the kitchen gardens.New Shirecliffe Hall – on the site of the car park.We have no pictorial representation of the old Shirecliffe Hall.Records of Old Shirecliffe Hall describe an 'ancient chappell'. Photographs of the new hall show a chapel tothe side and behind the house. There is nothing now to see of the house or chapel. The house is on the siteof the car park and the chapel site is now woodland. A geophysics survey of the area in 2016 by a group ofarchaeology students from Sheffield University revealed no ancient foundations. We assume that the chapelwas moved or rebuilt when the house was built to the side of the original Old Hall.The Lodge to the Hall and the main gateway to the drive can be seen on Shirecliffe Lane. The drive wouldhave crossed the top of Cooks Wood Road to approach the Hall close to the sculpture. Old buildings andwalls on Shirecliffe Lane could have been built from stone from the halls or some may be original.The 'new' Shirecliffe Hall c.1800Some photographs of the hall must have been taken after the general strike in 1926, when the last of OldPark Wood disappeared - local people cut down trees for firewood.

The Hall was inhabited by the Watson family until it was seriously damaged by bombing during World War II.It was said to have been used as a kennels before its demolition in 1963.During the 19th Century an application was made for a new roadway to cross the woodland toShirecliffe Hall because the existing road from Sheffield via Pitsmoor was too steep for horses todraw larger carriages. It is thought the road went north from the hall turning down the hill at HerriesRoad and returned to Sheffield along the side of the river Don.Shirecliffe Hall and ChapelPoint 3 The Dipping Pond – Cooks WoodWalk on the footpath to the left of the car park, turn left down the footpath into the wood and directly downthe hill.A short detour from the upper part of the footpath which forks to the right, takes you to a small spring, wherethe water appears from the hillside and runs below the path eventually to form the stream which feeds thesmall pond at the foot of the hill. A number of springs were recorded throughout the area.Mel Jones, local historian and author of the Parkwood Springs History leaflet, maintains that the nameParkwood Springs derives from ‘Shirtcliffe Park Wood’, which was a spring wood – where coppicing tookplace. However, local people feel that the name derived more directly from the many springs of water whicharose from the sandstone hillside.

On the steep descent look for the edging stones either side of the footpath, thought to have been installed orre-set during the 1960s/70s, when the area was re- landscaped as a youth employment scheme. You mayalso see areas where garden plants have invaded the woodland - possibly as a result of householderstipping garden rubbish or birds dropping seeds.Encroachment into the woodland by some householders extending their gardens has been addressed by theCity Council.Encroachment is a serious issue for wild areas such as Parkwood Springs and unless it is quicklyaddressed, parcels of land may be lost to private or business use. It is important for the City Council and theFriends Group to raise people's awareness to value Parkwood Springs as a public space and thereforerespect its boundaries.The dipping pond is at the foot of the hill behind the houses on Cooks Wood Road. The dipping platform atthe pond was installed c. 2007 as part of the City Council’s management work to make it easier for childrento study the pond life there.During the 17th and 18th centuries the woods were intensively managed. Woods where coppicing took placewere known as Spring Woods. Around the pond are examples of coppiced trees – trees which have been cutat the base to encourage multiple new stems to grow, which could then be harvested as poles or left tomature to increase the yield of timber.Multi-stemmed coppiced treePoles could be used for fences etc. but were also used to build theconical, (wigwam shaped) frame covered with turves for the charcoalburners to live in close to the charcoal pits.Wood was stacked in large pits, covered with soil and burned slowlywith restricted air flow to convert the wood into charcoal. The charcoalwas needed to add carbon to iron in order to forge steel.Iron was smelted from local rock, or in later years, imported to convert tosteel by the Bessemer process developed in Sheffield. Kelham IslandMuseum displays a Bessemer converter used at local steel works.Woodland close to the rivers where the forges and foundries werelocated provided a valuable source of carbon (charcoal) for this process.The name ‘Oaken Banke Wood’ - on old maps between ‘Cooks Wood’ and ‘Park Wood ‘ reflects thepresence of oak trees amongst the indigenous species growing at Parkwood - predominantly the sessile oak,where acorns are borne directly onto the twig and not on a stalk. The bark of the oak trees was stripped tomake a liquor used in the tanning process. There was a tanning mill at Rawson Dam – on Herries Road –first recorded in 1783. The Dam was still in use in the mid- nineteenth century by Rawson, Machen andOxspring, and coppicing continued until the end of the 19 th century.From the mid- nineteenth century the lower part of the woodland was gradually encroached and cleared forindustrial use. The Lords Wood was cleared first, followed by the lower parts of Oaken Bank Wood. However,the boundaries of the Lords Wood appear to have been maintained and the land sold as a block at a laterdate for the housing development at Parkwood Springs village.Point 4. Rutland Road Entrance – The Bird and the Boy.Continue to walk along the surfaced footpath from the dipping pond to the main ridge path, then headdownhill to the Rutland Road Entrance to Parkwood Springs.The path crosses an area of acid grassland and heath – a specific feature of Parkwood Springs. The openarea is heather-clad with occasional gorse bushes and an apple tree, possibly a survivor from the orchardswhich were reported to have been planted over the sunny south facing hillsides.

The Bird and the BoyThe sculpture was created by Jason Thomson and installed c. 2005.Jason talked to localpeople and schoolchildren in preparationfor producing hissculpture, which wasfinally inspired by a storyhe heard from someonehe met walking atParkwood Springs.As a child, the localresident had lived atParkwood Springsvillage and played in thearea. He had found aKestrel’s egg andsucceeded in hatchingthe egg and rearing thekestrel. The bird is the kestrel.The boy on the sculpture has an arm raised in the air holding a glove to represent the industry in the UpperDon Valley at the foot of the hill. If you look closely behind the sculpture, you will see an image of tools usedby Jason in completing his sculpture.The process Jason uses to produce his iron sculptures is to carve the sculpture from a large block ofpolystyrene with a very sharp kitchen knife and a specially made longsword to reach high parts. The carvingis then lowered into a foundry pit and packed with sand in the traditional method of mould -making. Molteniron is poured over the polystyrene, which disintegrates and the space is filled by the molten iron. Noxiousgases are ducted away. When the iron is cool the sculpture is removed from the pit and sharp edgessmoothed. At this point it is shiny grey in colour. Both this sculpture and the ‘Spirit of Parkwood’ sculpturehave been installed securely into reinforced concrete.After installation the iron begins immediately to rust, beginning with a golden tinge which gradually, butrapidly, turns to the deep rust colour – with a highly tactile finish.

Jason Thomson preparing the ‘Spirit of Shirecliffe’ Sculpture.Installing the sculpture

Point 5. The Lower RidgeWalk back up the path and continue along the edge of the ridge on the main path. Stop and look at the loweredges of the hillside when you can see below into the industrial valley.It may be easier to find a better view of the lower slopes of the hillside from the Walkley/ Netherthorpe sideof the valley at another time. The steep slopes here are unstable and not accessible to the public.The area below the Bird and the Boy close to Rutland Road - now an industrial estate - was the site of abrickworks located in a geological feature known as ‘the Neepsend Brickpit’. This is one of Parkwood’sSSSI s – a site of special scientific interest and a nationally important sedimentological site.The geological survey describes: ‘Rock outcrops to the north and east faces of the former quarry show ironstained sandstone, mudstones, shale and seatearth.’ Some Neolithic finds suggest early habitation, but littleevidence remains as a result of the quarrying.In the early part of the 19th century woodland was cleared to make way for quarrying, mining andbrickmaking. There was little coal to be mined, although the whole of Parkwood Springs was excavated forcoal during the 1930s, 40s and 50s. A seam of ganister – fire clay - was mined to line the furnaces for theproduction of steel.Ganister is a hard rock formed from a particularly dense clay. Ganister mining was a treacherous occupation.Whole families were left without men to support them, killed by asphyxiation by ganister dust in the mines.However, the brickworks used the seam of ganister and clay where it came to the surface at Neepsend andwas readily accessed.Ray Swift (Friends of Parkwood Springs) recalls playing on the clay heaps as a child. He said that childrenwould take lumps of clay and mould them into small boxes making holes in the sides. They would take themdown to the steel works where the workers would fire the boxes in the furnaces and fill them with burningoiled cloth (oily wap). The hot boxes would keep children’s hands warm in cold weather.As you walk up the hill you can see views across the river Don to the City centre, Sheffield Manor to the leftand Walkley to the right.To the right in the valley foreground, the existing chimney at Kelham Island steel works can be seen from thepath. The old infirmary building – now behind Tesco – can be picked out.The Neapsend Brick pit

The view of Sheffield City Centre from the ridge walkImagine the scene here in the 18th / 19th centuries, the valley filled with glow and smoke of the fires fromfurnace chimneys, the rhythmic crashing of tilt hammers and the clanking of machinery. All the river valleys,the Don, the Loxley, the Rivelin, were heavily used for small scale steel production. Walks up any of thesevalleys will give a glimpse of the industrial history through the use of the fast flowing water to powermachinery. Most local farmers had workshops with an anvil (a stiddy) where they made small folding penknives or they cut files – a dangerous process for workers who suffered from breathing in metal dust. Theknives were made in huge quantities and exported widely, many to the USA. The average life span of a knifegrinder was 25 years. Apart from breathing in metal dust, grinding stones could fracture causing terribleinjuries.During the early part of the nineteenth century there was a major influx of people migrating from the countryto the cities looking for work. Accommodation was in desperately short supply and people were housed byrogue landlords in overcrowded tenements surrounding small yards. Facilities and sanitation was poor ornon-existent. In Sheffield areas of the city centre were a maze of small yards surrounded by tenements witha communal water pump and one foul smelling privy for everyone to use. Disease was rife.The city of Leeds reported that during the 1840s the highest cause of death for small children was bylaudanum (opiate) poisoning, parents attempting to sedate their children to keep them quiet. Anthrax wascommon amongst workers in woollen mills. Rickets and Tuberculosis were rife caused by lack of fresh airand sunlight.Whilst in areas such as York and Saltaire philanthropic factory owners recognised the problem and builthousing to a high standard for their workforces, little attempt was made in Sheffield to improve livingconditions for the working class. People were largely employed in small scale units, often self-employedwithout a factory owner who could see the benefits of employing a healthier workforce.The rivers regularly flooded the valleys carrying foul water into people’s homes and with it epidemics ofcholera. Little was done until 1832 when the Master Cutler in Sheffield died of cholera in one of theepidemics. It was finally accepted that disease held little respect for social class and mass buildingprogrammes of small terraced houses with sanitation began – mostly privately rented – which continued intothe 20th century. Sheffield’s hillsides were covered with streets of small terraced housing. Some were back toback houses, but the majority had a small garden for growing a few vegetables. No back to back housingremains in Sheffield, but examples can be seen in Leeds.

Old Park Wood‘Around six o'clock on Sunday morning 23rd October 1864 a crowd of about 200 people gathered in aclearing in Old Park Wood. They had come to see Thomas Dawes and William Horner fight for a prize of 1.Dawes and Horner had been friends, with Horner training Dawes as a fighter, but they had fallen out after"some words about a woman". Horner had Joseph Potts as his second and Dawes was seconded by William"Brick Lad" Stenton, an unknown other man acted as umpire and timekeeper. The crowd formed a ring andDawes and Horner fought gamely, but fairly, though the fight "was not a friendly encounter". It was "a fairstand-up fight" and both men were "plucky" although there was some "hugging" and "throwing" in the finalround and Dawes received a blow under his left ear. Time was called after about eighteen minutes. Dawessat on his second's knee but struggled to rise when time was called again, he managed to stand but fellimmediately on his side and did not rise again. Joseph Vardy from Eldon Street worked in the same factoryas Horner and knew both men. He picked up Dawes who lived for about five more minutes while he held himup, but did not speak. When the crowd realised Dawes was dead they, the seconds, and the umpire all ranaway, leaving only four or five remaining. Vardy helped carry Dawes' body to The Bay Horse in Pitsmoor. Thepost mortem found that Dawes was a strong healthy man with muscles largely developed and no fat in thebody, the cause of death was concussion to the nervous system arising from outward violence. TheCoroner's jury returned a verdict of Manslaughter against Horner, Potts, Stenton and the unknown man whoacted as umpire and timekeeper.’Views of Victorian/ Edwardian housing – mostly built between the 1890’s and 1920.The view of the hillside across the Don Valley shows the terraced streets of Walkley clearly - some risingsteeply up the hillside, others following the contour of the hill. Houses are interspersed with churches, shops,schools and public buildings, libraries etc.Some of Walkley’s streets were built by groups of people who collectively bought land to be able to vote aslandowners. In Britain, universal suffrage for all men over the age of 21 was not achieved until 1918 and forall women over that age, not until 1928. Land ownership previously gave men the right to vote.Public sector housing schemes begun in the 1920s provided good quality housing for those returning fromthe first World War. Slum clearance schemes during the 1930s aimed to provide better housing – such as onthe Parson Cross Estate - to clear the yards and tenements in the city centre, making way for businesspremises.

However, Sheffield suffered severe bombing during World War II and a considerable proportion of its housingwas destroyed or damaged beyond repair. Much of the Victorian housing stock was in need of replacementor refurbishment.During the 1960s and 70s, the City Council chose wholesale clearances of the Victorian terraces. Largemultinational companies developed modern, high amenity, mass produced public housing. Sheffield’s plansto develop ‘streets in the skies’ received widespread acclaim from eminent architects across Europe.Schemes aimed to take into account the social fabric of the community as well as the architecture to providea model of 'modern' high density living.In Sheffield, land use was limited because of the heavy metal pollution in the valleys, which would have beenextremely costly to remove. Creating 'streets' in high rise development seemed a way of maintaining theneighbourly reputation of Sheffield communities whilst taking up little land. At its height Sheffield Councilmanaged more than 90,000 public sector homes – many

line the furnaces of the steel works. The views from Parkwood Springs over the city - through the Rivelin and Loxley valleys . Shirecliffe was a sub-manor gifted to the de Mounteneys after the Norman conquest in 1066 by the de Louvetots, to whom they were related. In 1392, Sir Thomas de Mounteney was granted a licence by King Richard II to .