Transcription

.

The Workbench Book

The Workbench BookScott Landis

First published by Lost Art Press LLC in 2020837 Willard St., Covington, KY, 41011, USAWeb: http://lostartpress.comTitle: The Workbench BookAuthor: Scott LandisPublisher: Christopher SchwarzPhotos: Scott Landis, except where noted or on p. 244.Distribution: John HoffmanCopyright 2020 by Scott Landis.Originally published in 1987 by The Taunton PressFirst printing of the Lost Art Press editionISBN: 978-1-7333916-8-9ALL RIGHTS RESERVEDNo part of this book may be reproduced in any form or byany electronic or mechanical means including informationstorage and retrieval systems without permission in writingfrom the publisher; except by a reviewer, who may quotebrief passages in a review.This book was printed and bound in the United States.Signature Book Printing, www.sbpbooks.com

AcknowledgmentsTo Gerald Bannatyne, who uses no workbench at all. Withwis dom and grace, he taught me more than he’ll ever know.owe thanks to a great many peopleand institutions for their unselfishcontributions. My first and greatestdebt is to the craftsmen themselves,many of whom appear in these pages. Your insights were always welcome, and greatly enriched my ownappreciation of the subject.I particularly want to thank JayGaynor, Richard Starr, Tage Fridand Ian Kirby for allowing me to include their written material in sidebars. Thanks also to: Jerry Grant, Rob Taruleand G.L. Gilmore for granting me access to their unpublished manuscripts; Sam Manning for the use of his drawings; Greg McAvoy for demonstrating his Emmert vise inthe photos on p. 139; Paul Kebabian for allowing me to photograph parts of his tool collection; and Charles Hummeland The Winterthur Mu seum for access to the Dominy andGreber collections. Photos have come from a number ofsources and these are credited where they appear throughout the book and on p. 244.I greatly appreciate the efforts of the following individuals, who read and commented on portions of the text: Michael For tune, Ron Hickman, Frank Klausz, Nina Maurer,Tom Nelson, Toshio Odate, Richard Schneider, Peter Shapiro and Simon Watts. Special thanks to John Alexander,who not only read several chapters, but vigorously challenged my assumptions and avidly shared my discoveries.The staffs of several museums, schools and companieswent out of their way to facilitate my research. I particu-Ilarly thank the people at: The Winterthur Museum; MercerMuseum; Han cock Shaker Village; Fruitlands Museums;Mt. Lebanon Shaker Village; Shaker Village at Chatham,New York; Colonial Williamsburg; The J. Paul Getty Museum; Mystic Seaport Muse um; Hordamuseet of Fana, Norway; Skoklosters slott at Baal sta, Sweden; The RockportApprenticeshop; Robert Larson Co.; C.F. Martin Co.; Record Marples Ltd.; The Paramo Tools Group Ltd.; and TheBlack & Decker Mfg. Co. Thanks also to Valerie Oakley at theSouthbury Public Library in Southbury, Con necticut, forher research assistance.Finally, I would like to recognize the vital role playedby three other friends and colleagues: Mark Kara, whorendered all the color and thumbnail drawings; HeatherBrine Lambert, who built many of the benches on paperand whose good eye is responsible for gracefully tuckingan unruly tangle of material between covers; and especiallyRoger Holmes, who helped me find order in the chaos. Hisgood ear and fine humor always encouraged me and helpedkeep my feet on the trail.If ever a book was written with the help of many, this isit. Hundreds of people, in several different countries, welcomed me into their workshops, their homes and theirlives. They freely shared their experience and my excitement–indeed, they fueled my momentum with their ownenthusiasm. I hope I have done them justice. Regardlessof what we all may have learned in the process about theworkbench and our craft, these many friends remain mygreatest reward. You have made the journey well worthtaking.

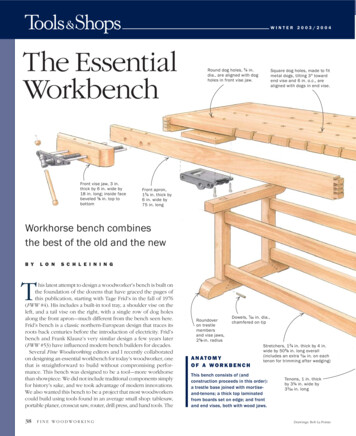

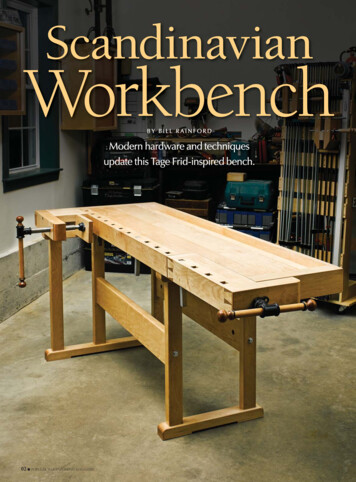

Foreworddon’t believe I saw an honest-to-goodness workbench until Ipicked up a copy of The WorkbenchBook by Scott Landis (TauntonPress, 1987).At my first woodworking job–buildingentrywaydoors–weworked on sawhorses. When I graduated to building folding tables, itwas worse than that–our work wasall done on an assembly line.And when I landed as an editor at Popular Woodworking Magazine in 1996, the shop there was equipped withbenches that were basically kitchen cabinets that had anold door for the benchtop and a quick-release vise.But the magazine did have a library.One night when I was working late, I spied The Workbench Book on the shelf. I was amused. An entire bookabout workbenches? That seemed a stretch. I flippedthrough the book, and the rest is history.I borrowed the book and read it several times over. Icouldn’t afford to buy a new copy on my salary, but I talked one of my fellow editors into selling me his for 5, ashe had sliced the cover off for photography. I wore thatbook out.The Workbench Book is the first and only survey of theentire world of woodworking workbenches, from Romantimes to the present. It covers Japanese benches, countrybrakes and shaving horses, commercial workbenches, andIbenches for specialized trades, such as boatbuilding, lutherie and carving.Though the book is only 248 pages, it is densely packedwith an astonishing amount of information, includingcomplete plans for a Shaker bench, Frank Klausz’s bench,Michael Fortune’s bench and Ian Kirby’s bench. Every pageoverflows with technical drawings, historical images andcontemporary photos of workbenches in use.Despite its technical nature, The Workbench Book is written in an intimate, conversational style, almost like a travelogue–but instead of visiting different countries, Landisvisits different workbenches, along with the people whobuilt and use them every day.As far as I am concerned, The Workbench Book has yet tobe eclipsed as the definitive work about the most important tool in the woodworker’s shop.Though I know almost every chapter of The Workbench Book like an old friend, I have a special place inmy heart for Chapter 2, which is about Roubo’s 18th-century workbench. In this chapter, Landis offers a translation of a critical section of Roubo’s text on workbenches. And he profiles Rob Tarule’s version of the Roubobench, which was built with a massive maple slab forthe top and the curious sliding-dovetail/tenon jointsthat fasten it to the legs.I had so many questions about that bench. What was itlike to build? What was it like to work on? How did that legvise and the crochet work? Could you really build furnitureon this beautiful beast?

A few years later–in 2005–I built my first Roubo workbench, and have since built 50 more during woodworkingclasses and for customers across the country. I’ve used thesame materials, joints and processes shown in Roubo’svolume but also employed modern machinery, construction-grade lumber and new vises. This bench, and its contemporary English cousin, inspired me to write dozens ofarticles and four books on benches.None of that would have happened without the directand nearly divine inspiration from Landis’s The Workbench Book.In 2020, I learned that The Workbench Book had goneout of print, and the rights had reverted to Landis. Thanksto an introduction by Robin Lee at Lee Valley Tools, Landisand I began talking about how to get The Workbench Book(and its companion, The Workshop Book) back in print.There were lots of technical problems–these books wereprinted during an awkward phase of the desktop publishing revolution.But thanks to Landis’s persistence and great patience,we’ve been able to bring this book back into print withtechnical specifications that meet or exceed the originalhardback volume.The book you are holding is produced entirely in theUnited States. It is printed on premium 100-percent recycled paper. Its pages are sewn, glued and affixed with a fibertape to keep it together. And the whole thing is wrappedwith heavy, cloth-covered boards and a sturdy dust jacket.The Workbench Book is a title that deserves to be in printfor as long as woodworkers need workbenches. The newedition is extremely durable and should survive having itscover sliced off–just in case some impoverished, low-levelmagazine editor in the far-flung future needs a jolt of inspiration.Christopher SchwarzCovington, KentuckyOctober 2020

ContentsIntroduction1Chapter 1The Evolution of the Workbench4Chapter 218th Century: The Roubo Bench18Chapter 319th Century: The Shaker BenchAn32Old-Fashioned Workhorse48Chapter 4Chapter 5A Modern Hybrid62Chapter 6A Basic Bench80Chapter 7A Workbench SamplerChapter 8BenchesChapter 9Shop-Built Vises120Chapter 10OtT-the-Shelf Vises136Chapter 11Japanese Beams and Trestles130Chapter 12Country Shaves and Brakes164Chapter 13Boatbuilding180Chapter 14Lutherie190Chapter 15Ca200Chapter 16The Workmate toMarketrving90114210AppendicesBench Plans222Bibliography242Credits244Sources oj Supply243I246ndex

IntroductionuffuThis intimate relationship-between the maker, his toolshy a book about workbenches?This book grew, in part, out of mypersonal attachment to tools. I'm oneand his bench-sses our working life. Experienced crafts men can navigate around their benches (and the inner recess of those fanatics who can spend morees of their shops) blindfolded as easily as some of us can findtime building a canoe than paddlingour way around the inside of a dark refrigerator.it.Regarding most subjects, I relishSuch rapport does not come overnight, and is not easily sev canthe journey at least as much as the ar ered. I've heard several stories that illustrate the bond thatrival. The workbench is no exception.develop between craftsman and bench. According to one story,diffiIt is the foundation tool of the wood an aircraft pattern shop preserves its benches even thoughworking trade, upon which all handwork is performed andthey have been made obsolete by modern machinery. The shopculty completing a singleretains one workbench per man, paying homage to the hand project. Although the bench takes different forms, it is perhapstool tradition, although the workers now only sit upon theirwithout which we would havepartthe only tool that is common to every branch of the craft-frombenches to eat their lunch. Another tale about a deceased Lith country chairmaking to urban cabinetmaking. That it is ubiq uanian cabinetmaker in New York City tells how his cremateduitous isashes are stored in a box on the shelf beneath his bench. Andl y the cause of its neglect. Library shelves arecrammed with books aboutfurniture,and to a lesser extentabout the tools that are used to make it. But none attach moreIt's no coincidence that antique benches are finding theirthan a passing interest to the workbench.Still, the bench had been a source of inspiration to my ownvirtuwork, and I was convinced that other craftsmen felt theevery Christmas his former co-workers fondly toast his mem ory by dumping a shot of vodka into the box.sameway into homes around the country, as sideboards, kitchencounters or simply for display. In a turbulent modern world,way. The workbench is to the dedicated woodworker what anthe workbench is a reminder (real or imagined) of a time wheninstrument is to theoso musician. In the hands of a mas men were measured by, in the words of the merchant Johnter, the bench can be made to produce works of brilliance; itWanamaker, ".the plumb of honor, the level of truth and thecan be 'played' with an almost audible clarity. Like a musicalsquare of integrity, education, coins"Thetrument, however, the bench is no better than the personusing it. At the same time, even the most skilled craftsmanwith the finest tools will be limited by a poorly made or ill conceived workbench.urtesy and mutuality."towhole earth is fun oj manumentsnameless inventors."-Otis T. Mason, The Origins oj InventianIntroduction1

On another level,In either case, I found that craftsmen often were surprisedthis book was inspired by a failed busi ness. Several years ago I was a partner in a bench-buildingby my interest.venture in Toronto, Ontario. We set forth (our naivete match do a job. Comparing their own bench to some imagined para Afterall, they protested, the bench was built toing our enthusiasm) to design and manufacture a workbenchgon of 'benchness,' they assumed theirs was too crude or tootumthat would take into account all that a workbench should be.ordinary to be of interest. They were usually wrong, but some 5.) We builttimes it happened that the workbench I went to see was not(The making of this bench is described in Chapterinto our benches the quality and detail you would expect tothe one that intrigued me. I might sfind in a bench you built for yourself.teresting detail elsewhere in the same shop or perhaps acrossble upon the most in I trucked a demonstration model to trade shows around thetown in the mind of another craftsman. Word of mouth led meNortheast to gain exposure. It drew many compliments but fewfrom bench to bench and shop to shop, from one end of thesales. In one instance, I eavesdropped on a revealing conversa country to the other.admwhat they thought was a respectable distance away from thelkinWhat began as a search for fine benches soon betion that took place between a woodworker and his wife atmore. Craftsmen are used to tacame muchg about their work, theirbooth: "Nice bench," said he. "You can make that," said she.design aesthetic, even their planes and chisels, but not about"Pretty pricey," heitted. "It's only wood," she added. He re their bench. Once encouraged, however, they embraced theurned later for a brochure and to check a few dimensions,subject passionately, as though discussing their own children.tdrummeven crawling underneath to mentally record the vise mechan They were glad to share their knowledge, but they were just asics. (It would have been unseemly to pull out a tape measure.) Ieager to find out what others had to offer. Like the travelingwasn't surprised

As far as I am concerned, The Workbench Book has yet to be eclipsed as the definitive work about the most import-ant tool in the woodworker’s shop. Though I know almost every chapter of - The Work bench Book like an old friend, I have a special place in my heart for Chapter 2, which is about Roubo’s 18th-cen-tury workbench. In this chapter, Landis offers a transla-