Transcription

Shaker Inspiration

Shaker Inspiration:Five Decades of Fine CraftsmanshipBy Christian Becksvoort

First published by Lost Art Press LLC in 201826 Greenbriar Ave., Fort Mitchell, KY, 41017, USAWeb: http://lostartpress.comTitle: Shaker Inspiration: Five Decades of Fine CraftsmanshipAuthor: Christian BecksvoortPublisher: Christopher SchwarzEditor: Megan FitzpatrickBook design and layout: Meghan BatesIllustrator: Jim RicheyDistribution: John HoffmanCopyright 2018 by Christian Becksvoort. All rights reservedISBN: 978-1-7322100-3-5Second printing.ALL RIGHTS RESERVEDNo part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical meansincluding information storage and retrieval systems without permission in writing from thepublisher; except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.This book was printed and bound in the United States.

AcknowledgmentsFor the friends and mentors who’ve helped me along the way: Max, Henry,Smith, Gus, Charlie, Mac, Bernie, Vincent, Alex, Tom, Anissa, David, Nick,Abe, and the Shaker craftsmen from whom I’ve learned so much.Photos unless otherwise noted, by Margaret A. Stevens-Becksvoort.Measured drawings by Jim Richey.

Table of ContentsIntroduction .ixSECTION I: The BasicsChapter 1: Know Your Materials .2Chapter 2: Acquiring Woodworking Skills.12Chapter 3: Solid Wood Furniture Construction .20Chapter 4: On Craftsmanship.42Chapter 5: On Design.50SECTION II: The BusinessChapter 6: Getting Started.62Chapter 7: Setting Up Shop.68Chapter 8: Goals & Business Considerations.76Chapter 9: Marketing.82SECTION III: InspirationChapter 10: My Designs – A Baker’s Dozen.94Chapter 11: Shaker Reproductions.122Chapter 12: Shaker Classics.138Bibliography.157

IntroductionOpinionated? You bet. Nobodygoes through life without forming strong likes, dislikes and opinions.Informative? Positive. Again, working at a craft for five decades or more,one acquires skills, knowledge andtechniques that want to be shared.Interesting and inspirational? I hopeso. Let me state right here and now,however, that this is not intended tobe the definitive last word. Nor is itintended to be a path to woodworking nirvana, nor a silver bullet for yourbusiness – and I’m not trying to foistmy inspirations off on you. I am not amarketing specialist, lawyer, financialadvisor or PR guru. What follows isjust an overview of what has workedfor me – a sharing of my experiences,failures and successes. Feel free to follow your own path. If any of my suggestions motivate or spark your owncreativity, all the better.Rigid? Not. I try to find a balancein my shop, and to suggest other options. I am not an “unplugged” or “silent” woodworker. I can’t make a livingwithout machines. Nor am I a power-ixtool fanatic. I think that items spit outby CNC machines are useful for massproduction, but have nothing to dowith craftsmanship. I use hand toolswhere it shows, and machines where itdoesn’t. You make your own choices.Remember what’s important to you,your family, your friends, your standards, your idea of “craftsmanship.”Remember to volunteer, to give backand to help others. Chris Becksvoort, December 2017

50CHAPTER 5

Chapter 5:On DesignDesign is an even more slipperytopic than craftsmanship. Back tothe dictionary. Design: “A plan, drawingor concept produced to show the lookand function, or workings, of a building, garment, or other object before itis built or made.” That’s way better thanthe craftsmanship definition in Chapter 4. Usually, a design starts with anidea or concept. What I’m really tryingto uncover here is how to develop anidea, or to put it more plainly, how doesone become a designer?Unless you are distantly related toLeonardo da Vinci, this is going torequire a bit of work, education andpractice. What, more practice? You bet;nothing comes easy. As I mentionedin Chapter 2, I learned how to readblueprints early on, and followed themmeticulously. A lifetime of merely following plans will make you a prettydecent woodworker, but not much ofa designer. You’ve got to give somethought to what you are building, andwhy it’s built this way. Engage mentallywith your work. Why is this drawer atthe bottom of the cabinet instead of atthe top? Question, evaluate, compare.FunctionThe biggest takeaway I’ve learnedfrom studying, admiring and restoring Shaker furniture is that it is firstand foremost functional. “All beautyrests on utility” and “That which in itself has the highest use, possesses thegreatest beauty.” These Shaker proverbs perfectly state their design ethic,nearly a century before Louis Sullivandeclared that “Form ever follows function.” These are words that I design by,that have served me well, that I stillkeep in mind each time a client wantsa new piece. From a furniture maker ordesigner’s point of view, that, I think,should be the first and foremost principle of design.If you’re predisposed to add yourown ideas, a curve, a flair, a new texture or color, whatever, that’s fine – aslong as your take doesn’t supersede orreplace the primary function of thedesign: to be useful and functional. Achair has to function as a chair. Is thattoo difficult a concept to grasp? I rollmy eyes when I walk into a gallery orstudent woodworking show and see atable with a slanted top, or a chair with51no seat. “Art furniture” is great, as longas it still meets its primary criterion –to be fully functional as a chair, table,desk or bed. If your idea of whimsy orcreativity overwhelms, interferes withor totally obliterates that primary use,then you’ve crossed a line. Call it sculpture if you’re so inclined, but don’t callit furniture. It gives us a bad name.An advertisement I came up with afew years back, and still use on occasion, reads, “Any artist can make something you’ve never seen before. Very fewcan create something you’ll want to seeor use for the rest of your life.” To quotethe Shakers again, “All beauty that hasno foundation in use, soon grows distasteful and needs continuous replacement with something new.” In otherwords, just because it’s different doesn’tautomatically mean it’s good or worthwhile. I keep reminding myself not tolet my sense of originality overwhelmmy sense of purpose. Function is indeedforemost when designing furniture.Historic PrecedentsOne can certainly do worse than tofollow or imitate historic pieces when

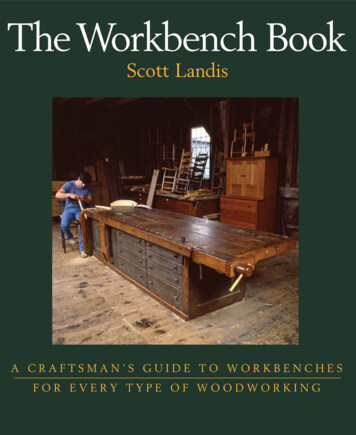

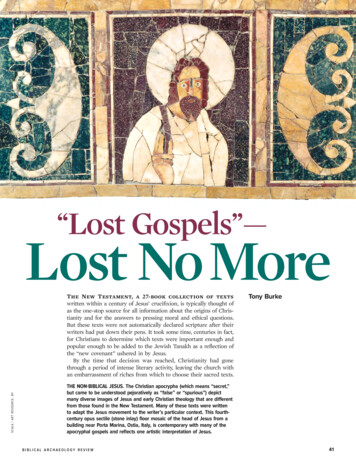

ern, what is functional, and my hopealways is that people will not be drawnto novelty, but will learn to value whatis simple and pure in good design. Andthings should do the job they were designed for. I don’t think that’s askingtoo much.” Sound familiar?The Danes took the Shaker designand functionalism to heart, and beganproducing their version. In the 1960s,they sold it back to us as “DanishModern.”Evolution of My Designs5-1. Queen Anne tea table. This is one of my early efforts, which made me appreciate the Shakerstyle even more.designing furniture. I think that’s howmany of us got our start. With an openmind and a willingness to learn, wecan gain tremendously from copyingexisting work. Subtle techniques, profiles, proportions and a different way ofobserving can all leave impressions onus when copying good or great worksfrom the past. Call it osmosis. Eventually you, too, will be able to discernwhat makes a great design as opposedto something just ordinary. For example, in one of my previous jobs, I wascalled upon to make Queen Anne tables and chairs. It took a while to master the technique of creating a cabrioleleg. It took even longer to distinguishthe subtleties of a really good leg froma ho-hum, or disproportionate leg.Eventually, I got it.To this day, I have deep respect forthe effort, craftsmanship and designthat goes into that style of furniture.However, I could never figure out whya chair or table leg would need an eagleclaw grasping a cue ball. To put it another way, that style never spoke to me.Shaker designs, on the other hand,52CHAPTER 5got my immediate attention. I grewup with Scandinavian furniture inour home. It turns out that in 1927, aShaker armed rocker found its way toDenmark, where it came to the attention of architect and designer KaareKlint. While teaching at the DanishRoyal Academy of Fine Arts, he had adrawing made of the chair and had students reproduce it. It was 10 years laterthat Edward Deming Andrews’ book“Shaker Furniture: The Craftsmanshipof an American Communal Sect” waspublished, and the Danes discoveredthe Shakers. The unembellished functionalism clearly struck a chord withthem.Designers such as Børge Mogensenand Hans Wegner were equally influenced by these designs. A Danish delegation actually visited the HancockShaker community and returned homeimpressed by the clean walls of drawers, peg boards and trestle tables. Mosthistorians consider Shaker furniture tobe the first modern style furniture. AsHans Wegner noted, “There is muchconfusion today about what is mod-I first became aware of Shaker furniture in college. In an art appreciationclass, during an otherwise uneventfulslide show, images of Shaker clocks,chairs, cabinets and built-ins madean appearance. I took note and something clicked. A few years later, whileworking in the Washington, D.C.,area, I chanced upon a Shaker exhibitat the Renwick Gallery of what wasthen called the National Collection ofFine Arts (now the National Museumof American Art). I went back manytimes, transfixed by the unadornedsimplicity. Little did I realize that decades later I would touch, measure andreproduce many of the very pieces I waslooking at. I bought, and still treasure,the catalog from that 1973 exhibit.Design ElementsDesign elements are merely a set ofguidelines, principles or standards thatdesigners incorporate when coming upwith a new idea. Each style of furniture has its own design elements, ordistinctive characteristics, that immediately identify it as “that” style. Forexample, Arts & Crafts has its exposedand protruding tenons, corner bracesand, of course, dark quartersawn oak.5-2. Catalog of the Renwick Shaker Exhibit,1973. This was my first encounter with actualShaker pieces.

On Design 53

5-3. Brainstorm sketches of apotential music stand.Shaker has its mushroom knobs, unadorned drawers, straight lines andlight ladderback chairs. French provincial is dripping with gingerbread, paintand gilding. And Chippendale has thecabriole leg, shell carvings and brokenpediments. In working in any of theseor other styles long enough, the elements become almost second nature,and part of your vocabulary. The moreyou study, practice and build, the moreit all becomes part of your inherentsense of design.Many woodworkers and designersstart by copying other styles, a great wayto learn. Eventually some develop theirown vocabulary, or voice. Sam Maloof,for example, was influenced early byDanish Modern, and soon developedhis own take, his own style. George Nakashima had deep roots in the Japanesedesign tradition, and was also influenced by the Shakers, but developed hisown distinct design principles.54CHAPTER 5Brainstorm DesigningI use what I call “brainstorm designing.” When a client wants a new piece,be it a music stand, bench or room divider, I first make a list of requirementsoutlined by the client. Next, I take timeto sketch out whatever comes into mymind. Pages of doodles. Any variation,no matter how wild, far out or impractical, is fair game. After a half-hour, orthree or four pages of multitudes ofdiverse alternatives, I call it quits. Figure 5-3 shows the last page of a musicstand brainstorm. Then I start examining, eliminating and combining ideas.Some are so far out in left field as to beworthless. They get tossed. Others havea hint of possibility – a curve or otherelement that makes them worth a second look. A few may be really close.Then I sketch out five or six possibleoptions to send to the client. Figure5-4 shows a few refined options for astanding mirror that I sent to custom-ers. They’ll either zero in on one designor want a combination of a few elements that they like from one or twoothers. Then it’s back to my drawingboard to refine the design. This goes onuntil both the customer and I are satisfied and in agreement.On occasion, it may become clearthat the client and I are not on thesame page. In other words, I won’t gobeyond my design elements, and theyare clearly searching for something different. It may turn out that they wanta ball-and-claw foot. I send them toa maker who is well-versed in thatstyle. No need for me to re-invent thewheel. More often than not, however,we come to an agreement on one ofmy designs, and we get started. Manyof my designs have been a direct resultof a singular design for a client, Figure 5-5, my signature 15-drawer chest,was such a design. The client, a collector, wanted “something about the size

5-4. Options for a standing mirror.of a file cabinet, with lots of differentsize drawers.” That design has beenmodified over the years, because I tryto never build the same piece twice.The dimensions, proportions, layout ormethod of construction get tweakedeach time. It makes my daily routinemore interesting, keeps me on my toesand my sense of design fresher.Desi

SECTION III: Inspiration Chapter 10: My Designs – A Baker’s Dozen . 94 Chapter 11: Shaker Reproductions . Evolution of My Designs I first became aware of Shaker furni-ture in college. In an art appreciation class, during an otherwise uneventful slide show, images of Shaker clocks, chairs, cabinets and built-ins made an appearance. I took note and some-thing clicked. A few years later .