Transcription

June/July 2004Volume 17, Number 2The Abell ReportWhat we think about, and what we’d like you to think aboutPublished as a community service by The Abell FoundationBaltimore City Community College: A Long Way To GoTwo Years Yield Few Meaningful Reforms, Underscore Deep-Seated ChallengesFacing Baltimore City Residents’ Largest Provider of Post-Secondary EducationI. IntroductionABELL SALUTES:“BEST”— Increasingeducational opportunitiesfor disadvantagedAfrican American studentsIn the mid-1970s shockwaves fromthe Brown v Board decision were resonating throughout Baltimore’s educationcommunity, presenting the leadershipwith a dilemma: Though the publicschools were becoming more integratedunder the law, the private schools werenot subject to the law and, at that point intime, remained what they had traditionally been—all white. Five Baltimore private school educators viewed the situation as unacceptable; they decided toright what they saw as a wrong, and torecruit disadvantaged Afro-American students and work towards integrating theirenrollments. The problem was—howwould the students be recruited and whowould pay the costs? And so in 1987, outof the mergers of earlier initiatives established to deal with the problem, BEST(Baltimore Educational ScholarshipTrust) was born.The mission of BEST was set outclearly from the start: “to encourage, support and increase the educational opportunities for academically talented, economically disadvantaged African Americanstudents from the Baltimore metropolitanarea.” Now in its 17th year, BEST hascreated a record that makes clear just howfaithfully the Trust has been fulfilling itscontinued on page 8Baltimore City Community College(BCCC) is the only chance formany Baltimore City residents toobtain a post-secondary education, find ajob with a career path, and earn a sufficient income to support a family. BCCC isalso a critical linchpin in Baltimore’s ability to build a competitive workforce. YetBaltimore’s largest provider of post-secondary education (with 7,300 credit students) has generally graduated fewer than270 students each year, a reflection of theinsufficient academic foundation that students bring to the college. BCCC has historically struggled to move studentsthrough its developmental or remedialprogram—review courses in math andEnglish that 94 percent of new enrolleesrequire. Of those students who do make itthrough and advance to college-levelcourses, many fail to realize their goal ofobtaining a certificate or degree. Studentswho apply to the nursing program, forexample, have already completed theirremedial courses, yet preliminary examsand courses show that many are stillunable to perform the basic skills taughtin BCCC’s developmental courses. As aresult, only one-fourth of students whoenroll in nursing each year ever completethe program.At the same time, BCCC represents asizable State investment. Unlike otherMaryland community colleges which relyon the State for just one-third of their public funding and local governments for therest, BCCC receives two-thirds of its public dollars directly from the State. Muchas it did with Baltimore City’s districtcourts, the State assumed funding responsibility when it took over BCCC in 1990.Add to these State dollars local and federal support, and 70 percent of BCCC’sannual budget—a projected 76 millionfor FY 2005—is taxpayer-funded. Yet thisState funding is not linked to any trueState oversight, a situation that has beenparticularly apparent in the last two yearsduring BCCC’s unsuccessful attempts atreform. These failures to strengthenBCCC have, in turn, severely limited thereturns on taxpayers’ substantial investment in the institution.Given both the sizable stakes of a successful BCCC and the college’s inabilityto fulfill its potential, this report concludesthat significant changes are required atBCCC, starting with a reconfiguration ofits Board of Trustees. On May 27, 2004President McKay resigned; in the wake ofhis resignation, the time is right.BackgroundWith a sizable influx of public dollarsearmarked for employment training andpost-secondary education and an overallannual student enrollment topping20,000, BCCC is positioned as a criticalplayer in local workforce development.That it boasts 37 percent of the City’s college-bound public high school graduatesalso makes it the most indispensable postsecondary institution in Baltimore City.1But at BCCC over the years, lowgraduation rates have continued to declinethrough 2003. The former BCCC President reported a significant increase of 514graduates in 2004 (The Baltimore Sun,May 25, 2004), but this number has notcontinued on page 2

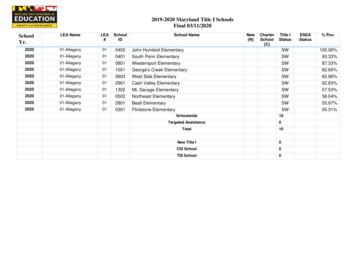

continued from page 1been officially documented. This juxtaposition of substantial promise and meagersuccess propelled The Abell Foundationto publish a 2002 report, Baltimore CityCommunity College at the Crossroads:How Remedial Education and OtherImpediments to Graduation Are Affectingthe Mission of the College. The reportdocumented low rates of student successand identified barriers that prevent students from obtaining certificates ordegrees and transferring to four-year colleges. Based on these findings it recommended that BCCC review its mission;overhaul its developmental studies program, particularly in math; strengthen student supports; and bridge the gap to Baltimore City’s public schools. To helpensure that the college had the tools tolaunch such reforms, The Abell Foundation hired a consultant to provide full-timeresearch support to BCCC from March2002 through December 2003.This report concludes the consultant’s work at BCCC. Using two years’worth of qualitative and quantitative data,it outlines changes that have occurred atthe college since 2001, discusses to whatextent reforms are taking root, and assesses the impact of these on students and thecollege’s operations overall. More importantly, it strives to help shape BCCC as atrue force for higher education andemployment in the City’s future.It appears that since the resignationof BCCC’s president, others have alsoseized that goal. State higher educationofficials have begun looking into issuespertaining to leadership and accountability at the college. On May 30, a BaltimoreSun editorial denounced the lack of oversight at the college and called for a newBoard and greater State accountability.II. BCCC TodayReflecting State and national trends,a majority of BCCC’s credit students arefemale (74 percent), attend college part-Percentage of BCCC Students Who Passed Developmental Courses by Level,Fall 1998 and Fall 2002; Five-Year Trend, Fall 1998 – Fall 200210SemesterCourse Number*Fall 1998Fall 20025-Year TrendMathematics11808182Reading1280818228% 31% 41 %40% 36% 46%32% 31% 41%64% 51% 55%69% 60% 61%66% 56% 58%time (67 percent) and work while inschool (72 percent; 44 percent fulltime).2,3 With respect to other student andenrollment trends across Maryland’s 16community colleges, however, BCCCdiverges from the norm. It has the largestconcentration of African American students—81 percent. Students in career programs at BCCC far outnumber those intransfer programs (62 percent versus 22percent in Fall 2003);4 by comparison,transfer students outnumbered career students statewide in Fall 2002 (45 percentversus 34 percent). Finally, while careerprograms in health services are increasingly popular at all Maryland communitycolleges, BCCC boasts the highest percentage of health services enrollment: 47percent of its career students are eitherenrolled in, or intend to enroll in, healthservices programs, compared to an average 35 percent statewide.5How BCCC Students Are FaringDuring the first half of the 1990s,BCCC awarded an average of 400 Associate degrees and 80 certificates. While certificates have held steady, the number ofdegrees fell dramatically from 442 in1994-95 to 257 in 1998-99 (42 percent infour years), and remained at that levelthrough 2003: BCCC awarded 261 Associate degrees in 1999-2000; 260 in 200001; 262 in 2001-02; and 261 in 2002-03.6As evidenced by rising remedialneeds of incoming students, BCCC isserving the State’s most unprepared college population. In Fall 1993, 84 percentof entering BCCC students requiredremediation in at least one subject—80English13818255% 54% 52%59% 65% 56%56% 59% 53%reading, English or math-based on placement test scores.7 By Fall 2002, nearly adecade later, 94 percent of first-timeBCCC students required remediation.8 Atthe same time, the actual amount of remediation required by students has alsoincreased. In Fall 1999, 61 percent ofentering students required remediation inall three areas—reading, English andmath; by Fall 2002 that number hadreached 67 percent. Specifically, 92 percent required remediation in math; 73 percent required remediation in reading and78 percent required remediation in English. By comparison, 32 percent of Maryland community college students requireremediation in reading, 34 percent requireremediation in English, and 52 percentrequire remediation in math, according tothe Maryland Higher Education Commission (MHEC).9On a positive note, pass rates fordevelopmental courses at BCCC haveincreased in reading, English and mathduring the last five years, from Fall 1998through Fall 2002. Albeit inconsistent,these increases are encouraging—particularly in the area of math. (As of Spring2004, when BCCC released the 2003 DataBook, its most recent, data reflecting passrates for Fall 2003 were incomplete, andthus not used.)Despite these improvements since1998, the overall success rate of developmental students at BCCC remains discouraging. According to the administration, 460 students repeated the samedevelopmental course for the third, fourthor fifth time in Fall 2003.14 By contrast, 84percent of community college studentscontinued on page 3The Abell Report is published bi-monthly by The Abell Foundation111 S. Calvert Street, 23rd Floor, Baltimore, Maryland 21202-6174 (410) 547-1300 Fax (410) 539-6579Abell Reports on the Web: http://www.abell.org/publications2

continued from page 2statewide pass their first developmentalmath and English courses, according toMHEC.15III. The Last Two Years: ASeries of Stunted ReformsInternal administrative shifts, external evaluations, and public attentionresulting from both have collectively laidthe foundation for significant changes atBCCC during the last two years. Every 10years the Middle States Commission onHigher Education extends accreditation topost-secondary institutions. In May 2003Middle States conditionally-renewedBCCC’s accreditation with recommendations centering on the need to revisitBCCC’s mission, engage in strategicplanning related to that mission, andimprove accountability and communication channels collegewide.16 The June2002 retirement of BCCC’s president of12 years, Dr. James Tschechtelin, alsospurred prospects for change. His successor, Dr. Sylvester McKay, had led anothercommunity college, College of the Albemarle in North Carolina, and arrived witha reform-minded agenda.During this time, The Abell Foundation, Middle States Commission, and others worked closely with BCCC to createstrategic frameworks for change. BCCC,in turn, implemented some significantreforms. The developmental reform initiatives BCCC has launched since early2002, however, have been plagued bypoor implementation. Ranging from theabsence of a strategic plan to guide thevarious reforms to a dearth of best practices- and data-based decisions drivingthem, numerous factors have impededBCCC’s three most significant reform initiatives, and limited their potential toincrease student success rates at the college: The Committee for ReformingDevelopmental Education, AcademicSystems Curricula, and the New Developmental Studies Division.1. The Ad Hoc Committee:A Year “On Hold”Following the March 2002 Abellreport BCCC launched, under its new VicePresident for Academic Affairs, Dr. JeromeAtkins, the Ad Hoc Committee on Reformof Developmental Education. Its charge, aspresented to BCCC’s Board of Trustees,was: “to conduct a comprehensive reviewof the Abell report (and developmentaleducation organization and delivery ingeneral), develop recommendations forcorrective action, and produce implementation plans complete with funding profilesand action timelines.”17 Meanwhile, the AdHoc Committee was held up by BCCC asa strategic blueprint among potential partners, and hailed during its 10-year accreditation process as a force likely to “have animpact on the course of developmentaleducation at BCCC.”18But within less than a year of its April2002 launch, the committee and its workcollapsed. The steering committee thatwas to lead it never materialized, and itssubcommittees produced little overall. Byearly 2003 the committee as a wholeceased to exist without any explanation.It was not until the Ad Hoc Committee was falling apart that its activitiesappeared on the Board of Trustees’radar—briefly in April 2003. The following month Dr. Atkins left the college, andthe committee was not mentioned againamong BCCC’s leaders. There were nosigns of accountability or oversight during its existence, and two years later, thereis nothing to show for its work. Theseabsences are troubling, given the hugeimport the Ad Hoc Committee wasascribed publicly by BCCC as a meansfor reforming the institution.2. Academic Systems: A Pilot ProgramWithout A NavigatorThe adoption of curricula/softwareproduced by Academic Systems Corporation has been BCCC’s highest-profile, andperhaps costliest, developmental reformof late. According to college purchaseorders, BCCC bought 699,060 worth ofsoftware, online course materials, andtextbooks from Academic Systems duringSummer 2003 and Fall 2003.BCCC decided to pilot AcademicSystems’ online math and English curricula in Summer 2002. The plan was ambitious: to have a “full-scale implementa-tion” underway by July 2003, “involvingstudents, faculty and facilitators at BCCCand all BCPSS high schools,” accordingto pilot proposals. The Abell Foundation,which contributed 28,000 to the pilot,had called in its March 2002 report foralternative modes of developmentalinstruction—a strategy supported by bestpractices research and BCCC’s ownexperimentation with self-paced anddevelopmental courses online. Meanwhile, data from community collegesusing Academic Systems suggested thatthe software improved developmentalpass rates among at-risk students nationwide. In November 2002 a BCCC studyteam visited Cuyahoga Community College in Cleveland, Ohio to observe justhow these gains were achieved.But BCCC did not make use of theseexperiences and research in devising anAcademic Systems implementation modelthat met the specific needs of its students.Details were still being hashed out in July2002, halfway through the first pilot phase,and participating BCCC students did notaccess the software until five or six weeksinto the eight-week summer session.Meanwhile, BCCC’s pilot goals werevague and shifting, and implementationfor Fall 2002 followed no approved plan.The English curriculum was added at thelast minute, creating confusion amongstudents about course requirements andfrustration about already-purchased traditional course textbooks. The Spring 2003phase of the pilot suffered from similarsetbacks; students did not have access totutorial software and textbooks until wellinto the semester. By the third week only15 percent of the 152 participating English students appeared to have and to beusing the software.19 English instructorsdid not follow a single protocol for monitoring student work and grading papers,further compromising the evaluation ofstudent progress.Perhaps most representative of theproblems plaguing the pilot was the Baltimore City Public School System’s decisionto halt a partnership between its highschools and BCCC. BCPSS’ Chief Technology Officer described the pilot as“another half-baked instructional intervention.” He asserted that “any new initiativescontinued on page 43

continued from page 3in this area should be well thought outwith real curricular goals, well designedevaluations, well thought through implementation, training and technical supportplans, etc., none of which are currently inevidence on this initiative.”20Finally, the pilot lacked accountability and consistent leadership. It did notinclude steps that Academic Systemsmaintained were critical to success, namely an evaluation plan and the hiring of aprogram coordinator. Throughout thepilot it was never clear who was in charge,and at no point did necessary leadershipcome from the top, despite the formerpresident’s assertion that computerizedinstruction was the future of BCCC’sdevelopmental instruction.Not surprisingly, the goals of the pilotwent largely unmet. Low levels of coursecompletion among students and the lackof any uniform protocol among instructors prevented pilot data from sheddinglight on the potential for increased studentlearning and retention. Yet in May 2003,BCCC adopted Academic Systems for alldevelopmental instruction, a decision thatwould cost BCCC 700,000 in its firstsemester.3. BCCC’s New DevelopmentalStudies Division: A Rushed StartOf the reforms BCCC has launchedin the last two years, the creation of a new,separate developmental studies division—the Center for Learning Programs—has been the most sweeping. Soincomplete was its launch, however, thatone administrator involved in its creationsaid the new division—absent criticalleadership and student services—still had“not gone into effect” as of the Spring2004 semester.According to BCCC’s July 2003 draftproposal, the new developmental studiesdivision would serve three of the college’sstrategic priorities: to improve studentrecruitment, retention and performance(its highest strategic priority); to improveresponsiveness to workforce needsthrough partnerships and collaborationswith businesses, industries and educational institutions; and to improve responsive-Percentage of BCCC Students Who Passed Developmental Coursesby Level, Fall 200323SemesterCourse 182Fall 200240% 36% 46%Fall 200348%--(Data Book)Fall 200353% 62% 71%(Board of Trustees)% Increase from66% 100% 73%Fall 2002 to Fall 200369% 60% 61%----ness to community needs.21 The proposalalso included broad goals, objectives, andexpected outcomes for the division; deadlines and responsible parties for eachaction; and promises for a new dean andnew faculty team specially trained indevelopmental instruction.But by the time the division waslaunched, none of these critical components were in place and deadlines wentunmet. No benchmarks for measuringfirst-semester student progress were everset. A new dean was never hired, andwhen at the end of the Fall 2003 semesterone finally was, BCCC’s Board ofTrustees overruled her appointment.22Among the many new contractual hiresfor the new division, few had any formaltraining in developmental education, andmany did not have a master’s degree inthe field in which he or she was teaching—a requirement of a questionable credentialing policy BCCC adopted in Spring2003. Meanwhile, the only training developmental faculty received was a cursoryworkshop in Academic Systems a weekbefore classes began.Finally, most planning for the newdivision took place a few weeks before thestart of the Fall 2003 semester. As a result,the launch was chaotic, and it was midOctober before major problems wereresolved. Most notably, full-scale implementation of Academic Systems softwarefor all developmental courses, the cornerstone of the new division, took place without the necessary infrastructure (technological hardware, trained instructors andwritten syllabi) to support it, resulting inseveral lost weeks of learning for students.While some of the problems thatplagued the new division’s launch havesince been resolved, many persisted intothe Spring 2004 semester. The divisionstill lacked a leader. Numerous instructorswere still ill-qualified to teach developmental studies. Some computer labs stilllacked computers and headphones—bothcritical to accessing Academic Systemsmaterials. Not all developmental mathinstructors were using the Academic Systems software, such that instruction andcurricula varied widely throughout thedevelopmental math program; nor wereinstructors following uniform guidelineswhen it came to testing, grading and generally evaluating student performance.Most importantly, there was no divisionwide final assessment in place that wouldindicate if developmental students weremaking academic progress as a result ofthese reforms.59% 64% 56%63% 65% 64%------63% 65% 64%------7%2%14%Results of Reforms: StudentPerformance Data InconclusiveDevelopmental pass rates that hadrisen in recent years continued to climbduring Fall 2003, the first semester ofresults for the Center for Learning Programs and for division-wide use of Academic Systems. Data were first released inthe college’s 2003 Data Book in December, and then re-released during Spring2004.BCCC officials attribute the suddenand significant jumps in developmentalmath pass rates (of up to 100 percent) forFall 2003 to recent reforms it has implemented. But a number of factors make itdifficult to determine to what extent, ifcontinued on page 54

continued from page 4any, these numbers actually representincreases in student learning, and thusauthentic progress. The above discrepancies among datareleased for Fall 2003 raise questions:Were students with incomplete gradesincluded in the pass rates for Fall2003 that were re-released in March2004, subsequent to the Data Book’spublication? Faculty assert that theseMarch 2004 pass rates also includestudents who took a “ second-chance”makeup course over the winter. Iftrue, this would invalidate these datafor any study of effectiveness ofreforms during the Fall semester. Developmental math instructors useddifferent curricula and instructionalmethods during Fall 2003 and subsequent makeup courses; in some cases, faculty assert, makeup courseinstructors did not even use Academic Systems. The only data issued by BCCC tomeasure the performance of its newCenter for Learning Programs duringFall 2003 are the above-cited passrates. Yet, it is not clear that improvedstudent performance is required topass a BCCC developmental course.At the College of Southern Maryland, by contrast, a final exam is alsoadministered to all developmentalmath students. There is no comparable measure at BCCC. “Nobodyknows exactly what the curriculumis; there’s no standardized test at all.It makes it impossible to compareother semesters,” asserts one BCCCmathematics faculty member, notingthat in the past a standard curriculumwas followed and final exams wereadministered. “Why should we saythat we made a difference for the regular [Fall 2003] semester?”This evidence of the poor implementation of Academic Systems and the Center for Learning Programs during the Fall2003 semester is inconsistent withBCCC’s results showing up to 100 percent increases in pass rates in one semester and deserves inquiry.Final Analysis: Poor ImplementationBoiled Down to Leadership BasicsDay-In and Day-Out, Leadership atBCCC is LackingThe Ad Hoc Committee, AcademicSystems and the Center For Learning Programs were all reforms that had merit.What they lacked were strategies toensure their success, which, arguably,should have been present with the oversight of committed leadership. But documented findings and observations, as presented in the full May 25 report, can leavelittle doubt among the most fair-mindedthat BCCC’s leadership of the last twoyears appeared to be marked by poorcommunication and non-inclusive decision-making. Ultimately, these shortcomings led to the lack of coherence andaccountability that has marked each ofBCCC’s recent major reform efforts.The institutional evaluation thataccompanied the Middle States’ reaccreditation of BCCC in May 2003 citesthe following concern about communication and leadership at the college, factorsthe evaluation team deems critical to ahealthy institution and, in this case, toBCCC’s successful reform:There seemed to be a generalconcern from all constituenciesregarding lack of timely information and clear and effectivecommunication . . . BCCC mustdevelop a governance structurethat will provide greater opportunities for communication, collaboration, and cooperationamong divisions and betweenadministration and other college constituencies—faculty,staff and students.— Middle States Commission,May 2003Yet in the months that followed theMiddle States report, BCCC’s administration acted in ways that highlighted itsauthors’ concerns regarding leadership atBCCC.The administration’s announcementin May 2003 that it would launch a newdevelopmental division in academic year2003-04 lacked specifics, and planningfor the division took place during latesummer by a select few. As a result, mostemployees left for the summer andlearned of major changes only upon theirreturn in the fall. The start of the Fall2003 semester was marked by a verypublic dispute between BCCC’s facultyand President McKay, in which facultyasserted that there had been “poor communication of the processes by whichdecisions are being made,” and the President responded with criticisms of the college, faculty and staff.26Such examples of lackluster communication have not been confined to therecent reform initiatives; nor, evidencesuggests, have they abated in the wake ofpublic reports and recommendations.Similarly suggested is a leadership styleamong BCCC officials that appears reluctant to do the hard work that true reformand change entail.President McKay publicly announcedlast fall that by January 2004 he wouldrelease a draft of the plan mandated in theMiddle States evaluation that previousspring. The plan discussed at a facultymeeting and planning session on January23 was instead a 45-slide PowerPointpresentation that listed existing and projected course offerings—hardly the“clearly defined Academic Master Planthat specifically addresses the issue ofremediation and the areas for academicprogram development as well as programreview” mandated by Middle States aspart of its reaccreditation.27 When a seniorfaculty member proposed improving theprocess for devising the academic masterplan, President McKay responded by saying he did not “have the flexibility of timeto start over.”28Time and again, college officials havemissed deadlines with no or insufficientexplanation provided, and produced statusreports and plans that are dated, recycled,and include both information that is nolonger correct or relevant and names ofresponsible persons no longer at BCCC.Examples include the strategic plans thecollege submits to the State Department ofcontinued on page 65

continued from page 5Budget and Management each summer,the annual Performance AccountabilityReports submitted to MHEC, and theSelf-Study submitted to the MiddleStates Commission in early 2003.Leadership on BCCC’s Board IsAlso InconsistentWhile daily leadership of BCCCappears inconsistent, such behavior is alsoreflected in the actions of BCCC’s Boardof Trustees. The nine-member bodyfocuses on isolated detail versus globalissues and critical oversight on the onehand, and usurps the President’s authorityon the other.The Board meets in both closed andpublic sessions, but the latter rarely entailany discussion of policies and plans thataffect the college’s ability to execute itsmission. Until Fall 2003, for example,there had been no mention during publicmeetings of the launch of a new developmental studies division slated for September 2003. Meanwhile, the first detailedpublic report to the Board on the newdivision did not take place until February2004, well after it was launched.29 Thishands-off approach is not the role theMiddle States Commission views as critical for BCCC’s Board. “The extent towhich BCCC’s faculty, administrationand governing board immerse themselvesin, and raise questions about, the institution’s performance, study their findings,search for remedies, and demonstrateimprovement in educational excellence isa primary indicator of institutional effectiveness and learning,” it stated in its May2003 evaluation.30 “Students, staff andfaculty expressed concern over the current lack of accountability.”Lately, the Board has been describedby members themselves and closeobservers as providing leadership that canonly be termed as vacillating—alternatelyclosely, and then distantly, engaged. Arecent example: President McKay’sappointments of two 80,000-a-yeardeans were rejected by the Board at itsDecember 2003 meeting because bothhires were the spouses of other Baltimorearea college presidents. At the same meet-ing the Board also fired the Vice Presidentof Learning, appointed by the President inJune 2003 to serve until a permanent VicePresident was hired, and unanimouslyadopted a new policy regarding delegation of authority that only allows the President to “recommend” ranking individualsfor hire.IV. New Leadership atthe Top: Giving Studentsthe Future They DeserveThis report’s analysis of BCCC’slong-term strategic direction and its dailyoperations points to weak leadership atthe college - not only at the president’slevel, but more critically, emanating fromBCCC’s Board of Trustees. To quote Statestatute: BCCC’s board must “exercisegeneral control and management of theCollege and establish policies to effect theefficient operation of the College, [and]appoint a President of the College whoshall be the Chief Executive Officer of theCollege and the Chief of Staff for theBoard of Trustees.”BCCC’s board has struggled to fulfill this mandate in the last two years. Ithas been largely absent on matters thatmost affect the college’s mission “to educate and train a world-class workforce forBaltimore.” It has been inconsistent in itsmanagement of those charged with running BCCC, as well as it public demandsfor accountability. In times of turmoil andcrisis it has failed to instill confidence inoutsiders that BCCC can and will

altimore City Community College (BCCC) is the only chance for many Baltimore City residents to obtain a post-secondary education, find a job with a career path, and earn a suffi-cient income to support a family. BCCC is also a critical linchpin in Baltimore's abil-ity to build a competitive workforce. Yet Baltimore's largest provider of .