Transcription

Cairns S, Sloman L, Newson C, Anable J, Kirkbride A & Goodwin P (2004)‘Smarter Choices – Changing the Way We Travel’Car clubs8. Car clubs8.1 IntroductionThe basic idea of a car club is that people can have access to a car in theirneighbourhood without having to own it. Typically, car club members pay an annualmembership fee to an operator (in the order of 100- 200) who provides andmaintains a range of vehicles in their neighbourhood. Members then pay by the hourand mile when they use a vehicle. Some operators prefer to charge a higher hourlyrate and do not ask for a membership or mileage fee. The combined costs ofmembership and use are intended to be cheaper than personal car ownership, for carowners who do not do a high mileage, and to encourage the adoption of relativelydiverse personal transport strategies. The idea was imported from mainland Europe inthe late 1990s.In June 2004, Carplus, the umbrella organisation for UK car clubs, was aware of atleast 25 car clubs in the UK with a reported combined membership of 1165 (Kirkbride2004). Clubs range from city-wide schemes run in conjunction with local authorities(e.g. Bristol) to independent clubs with only a few cars based in villages and markettowns (e.g. Moorcar in Ashburton, Devon). Some clubs have particular features. Forexample, Hour Car at Hebden Bridge in West Yorkshire uses vehicles that run on biodiesel; Rusty CarPool in Leicester involves renovation of older vehicles and a schemeset up in a low income area of Manchester forms part of a Local Exchange TradingScheme, so that vehicles are available to people with little cash. In terms ofmainstream schemes, key operators in the UK at the moment are Smart Moves,Urbigo and EasyCar. Details of many of the clubs can be found on the Carpluswebsite www.carclubs.org.uk.Most UK clubs have been developed from the bottom up: that is, projects haveemerged from local interest. Usually, vehicles are distributed around the localneighbourhood in convenient locations, members are attracted by advertising andword-of-mouth, new cars are added to the scheme as membership grows sufficientlyto support them, and there is a sense of belonging to a ‘community club’. In 2003, thevehicle rental firm EasyCar decided to trial their own version of a car club, byintroducing 27 vehicles at one site near Edgware Road in central London. They theninvited 3000 people to join, who were regular customers of their conventional carrental service who always returned their cars on time, in good condition. To someextent, this stretches the definition of ‘car club’, being more akin to a rental depotloyalty scheme (LTT 2003, Meaton 2003).The potential for car clubs in the UK was reviewed by Bonsall (2002) in a reportcommissioned by DTLR and the Motorists’ Forum. The report was deliberatelycautious in nature, avoiding drawing many conclusions, with the author highlightingthat "the literature on car clubs is limited in nature. Much of the documentation issuedin recent years is produced by those with interest in the field and is poorly referenced.There is little academic work on the subject of car clubs and it has not been possibleto examine and substantiate all the claims that have been made for the success of carclubs." However, whilst the report itself avoided many definitive statements, theReport by UCL, Transport for Quality of LifeThe Robert Gordon University and Eco-Logica191Final report to the Department for Transport,London, UK

Cairns S, Sloman L, Newson C, Anable J, Kirkbride A & Goodwin P (2004)‘Smarter Choices – Changing the Way We Travel’Car clubsMotorists’ Forum (2002) subsequently produced a summary report with more specificconclusions. In particular, they argued:"Our view is that car clubs are most likely to succeed organically in denseurban areas where there is good public transport provision and parkingconstraints. However, we do not believe that the perceived benefits of carclubs are presently sufficient to warrant a significant injection of publicmoney to support individual projects without further research."In their response to the report, the government essentially accepted this view and hasnot provided mainstream support for individual car clubs, although they continue tosupport the umbrella organisation, Carplus.Although the support for Carplus is welcomed, the car clubs community hasexpressed disappointment at the general conclusions, with a formal rejoinder byKirkbride 2003. This emphasised the reported benefits from car clubs, their potentialto be a complementary element of a sustainable transport policy and argued that theyare likely to be appropriate in more locations than the Motorists’ Forum believes. Inparticular, Kirkbride highlighted ongoing work between the Countryside Agency andCarplus to introduce 13 pilot car clubs in rural areas, of which five are nowoperational. He states that membership growth in these pilot rural clubs (in terms ofnew members per year per car) is typically higher than in many urban clubs.According to Carplus (forthcoming), currently, in the UK, on average 4.5 membersare joining per car per year in urban areas, whilst 8.2 members are joining per car peryear in rural areas.In the remainder of this chapter, Sections 8.2-8.4 primarily explore the internationalevidence that is available about the scale and impacts of car clubs. The subsequentsections report on our detailed examination of experience in Edinburgh and Bristol,together with some available material from other UK car clubs.8.2 Literature evidence on growth of car clubsCar club membership in Switzerland has been growing rapidly since the mid-1990s.Membership growth has been helped by the various car clubs joining forces to form anational organisation, Mobility CarSharing Switzerland, and by initiatives such as acombined season ticket marketed with Swiss Railways. In 1990 the number ofmembers of car clubs in Switzerland stood at about 500 (similar to numbers in the UKin 2002). By 1997 it had increased to more than twenty times this figure, and by 2003it had grown more than a hundred-fold to 58,000 members.Growth has also been rapid in Germany, although there the pattern has been slightlydifferent, with a number of car clubs in existence. The German umbrella associationfor car clubs reported a total membership of 55,200 in 2001, following growth of over20% a year for several years. Membership is conservatively estimated to reach over200,000 people by 2010, (Bundesverband CarSharing 2002). Although there are manycar clubs operating in Germany, the trend is towards consolidation and merging, sothat around 65% of German car club members are served by companies with over2000 members, and only 13% are served by companies with less than 500 members(Traue 2001).Report by UCL, Transport for Quality of LifeThe Robert Gordon University and Eco-Logica192Final report to the Department for Transport,London, UK

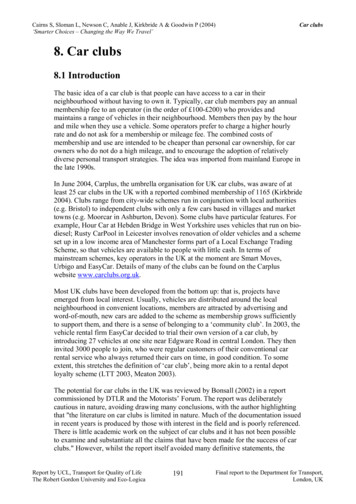

Cairns S, Sloman L, Newson C, Anable J, Kirkbride A & Goodwin P (2004)‘Smarter Choices – Changing the Way We Travel’Car clubsData was also obtained for growth of car club membership in one city in Germany,Bremen, (Glotz-Richter 2003). The car club in Bremen was launched in 1990, withthree cars and 28 members. Initial growth was slow, increasing to 500 members by1994 and 1200 members by 1998. This was followed by a membership surge (to 1900members in 1999) and then growth of about 200 – 250 members per year, reaching2900 members in September 2003.Car clubs in North America took off in the late 1990s, and Shaheen et al. (2002)report that by mid-2002 US car clubs had between them approximately 11,500members, and Canadian car clubs reported a total of 5065 members. By winter2003/04, the Carplus newsletter reports that US car clubs in 8 cities served by thethree main players (Zipcar, Flexcar and City Carshare) had over 30,000 members.Communauto in Québec (Canada) has grown to over 3000 members in 7 years, andZipcar in Boston attracted an impressive 4000 members in its first 3 years.In both Germany and North America, most of the growth in membership has been aconsequence of established car clubs getting larger or expanding to new cities, ratherthan new organisations being set up. For example, there are 14 car clubs in the US,but 92% of US car club members belong to the three main players, City CarShare,Flexcar or Zipcar, all of which operate in several cities (Shaheen et al 2002). InGermany, the largest 13 car clubs (out of 66 belonging to the German car clubassociation) serve 85% of all members, but these are spread right across the countrywith almost all cities of over 200,000 people now having a car club, (BundesverbandCarsharing 2002). In Switzerland, the national car club Mobility claims a presence in390 communities, (Mobility 2002).It is noteworthy that car clubs have been promoted in different ways in differentcountries. For example, in Germany, they have been targeted at the environmentallyaware. In contrast, for example, in Boston, they have been marketed as a smart featureof city living.Figure 8.1 shows that the growth in number of UK car club members is comparable tothe early years of the Mobility club in Switzerland. The inset suggests that the rate ofgrowth of UK clubs is falling behind that of Switzerland; this is mainly due to themembers lost between the collapse and re-launch of the Edinburgh car club. The UKdata do not include members of the Easy Car initiative in London.Report by UCL, Transport for Quality of LifeThe Robert Gordon University and Eco-Logica193Final report to the Department for Transport,London, UK

Cairns S, Sloman L, Newson C, Anable J, Kirkbride A & Goodwin P (2004)‘Smarter Choices – Changing the Way We Travel’Car clubsFigure 8.1: Car club membership growth in the UK compared with Switzerland6000050000Members4000030000Mobility (CH)UK120010008006004002000Car club growth in the UK7060carsmembers50123453002020010123456789 10 11 12 13 14 15 005004020000800Years from startSource: Kirkbride 2003. Figures exclude members of the EasyCar scheme8.3 Literature evidence on the target market for car clubsIn Switzerland, Muheim (1998) estimates that approximately 9% of the population arepotential car club members. This is based on an evaluation of the number of peoplewhose personal circumstances mean they could benefit from a car club, combinedwith survey data which found 36% of potential users were very or fairly interested inthe idea.In the US, Sperling et al. (2000) found that 15% of an experimental group in an areawell-suited to a car club became members of car club, CarLink, after receivingtargeted information and personal contact. She postulates that intense marketing ofcar-clubs to a carefully selected target population can elicit up to 15% participation.Both these estimates of the potential for car clubs are broad-brush, but they are in linewith estimates from a more detailed Austrian study (Steininger et al. 1996). Steiningersurveyed 198 members of Austrian car clubs to identify the characteristics of“pioneer” car club members, or early adopters, and from this developed a profile forpeople most likely to join a car club: Age 25-43 Highly educated (university degree or university entry level) Own at least one car, but not in a high price bracket Yearly car mileage for one car below 15000 km Less than 33% of trips currently made by car (based on car modal share for carclub members after joining) Currently involved in environment-protective action.He then surveyed 350 non-car-club members in two urban residential areas of Graz,and found that in one area, deemed an “average” urban residential area, 8.8% ofresidents had the right profile to be car club early adopters. In the second area, with ahigh academic population, the figure was 16.0%. Steininger argues these figures areprobably an underestimate. Some residents in the areas surveyed were excludedbecause they made more than a third of trips by car, and yet their car modal sharecould be expected to fall once they joined a car club. Taking account of these extraReport by UCL, Transport for Quality of LifeThe Robert Gordon University and Eco-Logica194Final report to the Department for Transport,London, UK

Cairns S, Sloman L, Newson C, Anable J, Kirkbride A & Goodwin P (2004)‘Smarter Choices – Changing the Way We Travel’Car clubspeople, the pioneer potential in the first residential area rose to 17.7% and in thesecond area to 37.6%. Steininger further argues that this is not the absolute upper limitfor car clubs: once it becomes a familiar concept it may expand to other groups andsocial segments, and its attractiveness will also grow if the “complementary good” ofpublic transport becomes better.Carplus (2004) provide data on their website for a sample of car club members in theUK, who belonged to clubs using cars sourced through the partnership betweenCarplus and Vauxhall Motors Ltd. 258 members were surveyed in August 2002. Thesocial profile that emerged was remarkably similar to that shown in the Austrianstudy. In particular: 77% of members were aged 23-49 (including 12% aged 23-29; 38% aged 30-39and 27% aged 40-49), and 86% of members were in professional and managerial jobs (55% recordingthemselves as professional, 22% as managers and administrators and 9% asassociate professional and technical)However, again, it should be noted that this is the profile of existing UK car clubmembers, who, by definition, can be defined as city-based ‘early adopters’, since carclubs are relatively new in the UK and have largely been developed in cities. Carplus(forthcoming) report on a survey of 36 rural car club members (who were surveyed onjoining one of five clubs between October 2003 and March 2004). Although only asmall sample, it suggests that rural car club members tend to be slightly older, andfrom a much broader range of social classes, including more housewives and retiredpeople. In particular, about only 60% report that they are in professional jobs (and nomanagers have yet joined).In brief then, international literature suggests that perhaps 9% of the population mightbe attracted to car clubs, rising to as high as 38% in certain areas. UK data of car clubmember profiles suggest that the UK experience of city car clubs is similar toelsewhere, although car clubs in rural areas may appeal to a slightly different socialprofile.8.4 Literature evidence on the effect of car club membershipon car useSeveral studies have evaluated “before” and “after” levels of car use amongst peoplewho join car clubs. Briefly, these studies demonstrate that members who give up theircar on joining a car club are able to reduce their car mileage by 60 – 70%. Car clubmembers who do not give up a car (either because they never had one or because theyare treating car club membership like a second household car) seem not tosignificantly alter their travel patterns. The main studies are Muheim (1998) andMeijkamp et al. (1997), and their findings are summarised in table 8.1.Report by UCL, Transport for Quality of LifeThe Robert Gordon University and Eco-Logica195Final report to the Department for Transport,London, UK

Cairns S, Sloman L, Newson C, Anable J, Kirkbride A & Goodwin P (2004)‘Smarter Choices – Changing the Way We Travel’Car clubsTable 8.1: Distance travelled by car before and after joining a car clubAverage annual km of .Muheim(1998)Members who give up a car on joining the schemebefore9300after2600Change in km driven-72%Non car ownersbefore 3100after3100*Change in km drivenlittle changeMembers who keep their car on joining the schemebeforeafterChange in km drivenThe average car club memberbeforeafterChange in km drivenMeijkamp etal. (1997)133804730-65%53603820-29%2170022386 3%84505660-33%* Car mileage of non-car owners after joining car club is inferred. Muheim (1998) reports this grouponly slightly changed their travel behaviour on joining the club. This includes getting lifts and borrowing vehicles from friends and familyMuheim (1998) analysed the travel patterns of 511 car club members and 340potential members in Switzerland, and found that members who gave up their own carwere able to reduce their car mileage by an average of 72%, from 9300 km per year to2600 km per year. This brought their level of car use into line with non-car owners,who, despite not owning cars, still travelled about 3100 km a year by car (for examplegetting lifts or borrowing vehicles from friends or family). Muheim reports thatpeople who did not own a car before joining a car club, or who used a car club inaddition to their own car, only slightly changed their travel behaviour.Meijkamp et al. (1997) undertook a similar analysis of reported mileage before andafter joining a car club, amongst 337 members of Dutch car clubs. For car clubmembers taken overall, the average reduction in distance driven was 33% or 2790 km(from 8450 to 5660 km per year). However, this masked substantial differencesaccording to whether or not people had owned a car before joining, and whether theykept it once they were members. People who gave up their car on joining the car club(“substituters”) reduced their car mileage by 65%. Those who used the car club inaddition to their own car slightly increased their overall mileage by 3%. Surprisingly,Meijkamp et al. found that car club members who had previously been without a car(“new car drivers”) reduced their car mileage by 29% on joining. (One plausibleexplanation for this apparently counter-intuitive result may be that car clubmembership encourages more conscious choice of mode and increases knowledge ofthe actual cost of driving a car. This seems to be borne out by an attitudinal survey ofthe people in Meijkamp’s study.)Reports for the EU MOSES research project (Traue (2001) and MOSES / UITP(2002)) quote several figures for reductions in car mileage: a reduction from 13000car driver km per year before joining to 3000 km per year afterwards, representing areduction of 77% and 10,000km (Munich); a decrease in car driver mileage of 71%(cambioAachen); a decrease of 57% (Swiss study); and a decrease of 50% (Germanstudy). While these broadly corroborate the studies by Muheim and Meijkamp, it isnot clear whether these figures refer to the average change for all car club members,Report by UCL, Transport for Quality of LifeThe Robert Gordon University and Eco-Logica196Final report to the Department for Transport,London, UK

Cairns S, Sloman L, Newson C, Anable J, Kirkbride A & Goodwin P (2004)‘Smarter Choices – Changing the Way We Travel’Car clubsor the change for members who have given up a personal car. Carplus (2004) reportthat, in Berlin, the average mileage per car club member dropped from 5425 miles to2560 miles, a reduction of 53% or 4,600km; and that in Bremen, the mileage of theaverage car club member has fallen by 3,500 miles (5,600km).Given the substantial differences in car mileage between those people who give uptheir personal car and those who do not, it becomes important to know whatproportion of car club members fall into each category. This issue is explored byMeijkamp and by several other German studies, summarised in Sperling et al. (2000)and listed in table 8.2.Table 8.2: Vehicle ownership patterns before and after joining a car clubWagner(1990)Would never buy a car (%)Gave up car independent of car club (%)Foregone planned car purchase due to car club (%)Gave up private car because of car club (%)Continue to own private car 32233Meijkampet al.(1997)71219Adapted from Sperling et al. (2000)Although there is a lot of variation in the figures, it seems that: Between 35% and 71% of car club members previously did not own a car: eitherthey had never owned one, or they had sold it some time earlier. Although theevidence from Meijkamp’s study suggests this group might reduce their carmileage, it seems safer to assume that they will not do so. A much smaller percentage, 3 – 9%, continued to own a car after joining a carclub. From the evidence presented by both Muheim and Meijkamp it seems likelytheir car mileage will go up a little, but they make up such a small proportion ofcar club members that this will have little impact on total “after” mileage. The remainder, between 21% and 58%, either gave up a car when they joined acar club, or chose car club membership instead of buying a car. For this group, itseems reasonable to assume a substantial reduction in car mileage, of the order oftwo-thirds, compared to what would have happened if a car club had not beenavailable.In summary, it seems reasonable to expect somewhere between a fifth and a half ofcar club members will give up their cars as a direct result of joining a car club, and asa consequence of this will reduce their car mileage by a substantial margin of aroundtwo-thirds. Car club members who do not give up a personal car will not change theirtravel patterns very much on joining a car club.8.5 Selection of car club case studiesCar clubs are still in their infancy in the UK. The most substantial and longestestablished is the Edinburgh car club, which was therefore a clear case study choice.The Edinburgh club began in March 1999, received a substantial blow when Budget,Report by UCL, Transport for Quality of LifeThe Robert Gordon University and Eco-Logica197Final report to the Department for Transport,London, UK

Cairns S, Sloman L, Newson C, Anable J, Kirkbride A & Goodwin P (2004)‘Smarter Choices – Changing the Way We Travel’Car clubsthe car rental company, dropped out in March 2001 (due to international financialproblems) and has since re-established itself as a partnership between the council andthe company Smart Moves.Other clubs that were looked at as potential case studies for this project were based inBristol, Bath, Oxford and London. In the end, Bristol was chosen, given that it isreasonably well established (having been launched in July 2000), and we wereinterested in the potential synergy with other initiatives taking place in Bristol. Themain drawback of this decision was the similarities between the Edinburgh andBristol schemes, as both operate in conjunction with Smart Moves. The other mainnational players are Avis car hire, who are involved in schemes in Oxford and Londonusing the brand name Urbigo, and EasyCar, with their new model of car club, (asdescribed in the introduction). Both of these organisations may also play an importantrole in how car clubs expand in the UK.During the course of the case study work, it emerged that Cambridge may beconsidering a car club for one of its residential areas in the future, and that the MiltonKeynes car share scheme was originally set up with a car club element (although thisproved unsuccessful - largely, according to the organisers, because the hire cars wereavailable close to people's workplaces rather than their homes).In summary, the main case studies for car clubs were: Bristol City Car Club Edinburgh City Car Club.From the other case studies, there was some information from: Cambridge Milton Keynes.As part of the shortlisting process, we collected limited information from: the Bath car club, run by Envolve, a local environmental charity Urbigo car club in Oxford, involving Avis Urbigo car clubs in Sutton and Southwark, involving Avis London City Car club, involving Smart Moves, with sites in Camden, Kensingtonand Chelsea, Islington, Lambeth, Merton, Ealing and Brent.There was also some available information about car clubs registered on the Carpluswebsite, and we received some material from their forthcoming report about theirpilot work on rural car clubs, being undertaken with the Countryside Agency.8.6 Details of chosen car club case studiesEdinburgh: The Edinburgh City Car Club was the first major car club in the UK. Itwas launched in March 1999, with financial support totalling 253,000 from the citycouncil, Scottish Office and DETR. Initially it was operated by Budget Rent a Car,who over a period of two years grew the operation to 170 members, 22 vehicles and23 sites. However, Budget abandoned the car club in March 2001. In October 2001,the Car Club was re-launched by Smart Moves with a development grant of about 40,000 from Edinburgh City Council, and considerable work was needed to regainReport by UCL, Transport for Quality of LifeThe Robert Gordon University and Eco-Logica198Final report to the Department for Transport,London, UK

Cairns S, Sloman L, Newson C, Anable J, Kirkbride A & Goodwin P (2004)‘Smarter Choices – Changing the Way We Travel’Car clubsmembers. At the time of the case study interview (July / August 2003) the club had215 members and 17 cars at 15 sites around the city. By April / May 2004 there were317 members and 19 cars.Bristol: The Bristol car club originated through a partnership between a voluntarygroup (Bristol Community Car Club Association) and Bristol City Council. It waslaunched as BEST (Bristol Environmentally Sustainable Transport) in 2000. and renamed Bristol City Car Club in 2001, when Smart Moves took on a more instrumentalrole in its operation. The council agreed a four-year funding package, starting in 2002,totalling 160,000. At the time of the case study interview (July 2003) it had 92members and six cars. By April 2004, there were 160 members and 11 cars. Membersof the scheme are entitled to a 10% discount on tickets on First Bus.8.7 Staffing and budgets for car clubsTable 8.3 compares the staffing and budgets for the Edinburgh and Bristol car clubs.Table 8.3: Comparison of staffing and budgets for car clubsEdinburghLength of time scheme has been2 years*runningNumber of car-club members215registered Number of regular users Not knownStaff time at local authority onceVery lowscheme establishedStaff time at car club operator 2 fteStart-up grant 48,000 invested inBudget scheme#,plus 39,750 grantto Smart MovesschemeOther annual costs to local authority 6000Total cost to date 99,750Bristol3 years9260Very low1.5 fte 50,000 grant so far,with another 110,000 committedNo costs apart fromcore grant 50,000* Current scheme operated by Smart Moves Figures are for time of case study interview (July 2003)# Funding for feasibility study and parking infrastructure Note that the cost of designating car parking bays was not separately identified by the case studylocal authorities, but other local authorities have identified this as a significant cost, at least in theinitial stages of establishing a car club.Both clubs have rather low staff time requirements within their respective localauthorities, as day-to-day management is carried out by Smart Moves staff. The mainroles of council officers are involvement in steering groups; liaison between the carclub and other parts of the local authority; and arrangement of traffic orders andsigning for car club parking spaces.Report by UCL, Transport for Quality of LifeThe Robert Gordon University and Eco-Logica199Final report to the Department for Transport,London, UK

Cairns S, Sloman L, Newson C, Anable J, Kirkbride A & Goodwin P (2004)‘Smarter Choices – Changing the Way We Travel’Car clubsThe car clubs themselves each have a full-time co-ordinator, and in Edinburgh there isalso a part-time assistant. Both clubs receive some support from the Smart Moveshead office in Coventry, including call-centre support.The current car club in Edinburgh has benefited from the research and investment thatled to formation of the previous car club, operated by Budget. This totalled 253,000,of which 150,000 covered initial set-up costs, 55,000 was for monitoring andevaluation, and 48,000 (in kind) was for a feasibility study and the cost of parkinginfrastructure at car club stations. In addition, over 200,000 was spent onpromotional activities while Budget was operating the car club. It is difficult toestimate the value of this investment to the current car club. Key benefits were thatthe current club inherited 60 members from the Budget car club, and that car parkingbays were already designated. However, Smart Moves were not able to use theoriginal Budget technology, and had to invest in new technology themselves –highlighting that equipping each car with the relevant technology typically costs 1000. They also had to overcome the reputation of the previous scheme of beingunreliable. We therefore tentatively assume that the 48,000 spent on feasibility workand parking infrastructure might reasonably be considered to have been of directbenefit to the current car club, but that other investment in the Budget scheme has notresulted in any particular benefit to Smart Moves.City of Edinburgh Council subsequently provided Smart Moves with a grant of 39,750 to cover operating deficits in the first two years (from May 2001). Thebusiness plan at that time forecast that the club would be able to operate withoutfinancial support after two years, and would move into profit in 2003/04. Membershipgrowth has been slower than forecast in the business plan, and, at the time of our casestudy interview, the club was intending to seek further development funding from thecity council. However, it expected to reach break-even point (around 500 members,representing about 7% of current car owners) by the end of 2004. In addition to thegrant of 39,750, the city council contributes about 6000 per year towardspromotional costs such as printing leaflets. Some costs are also associated withpreparation of traffic orders for parking spaces. These are met from the parkingbudget.In Bristol, there is also financial support from the local authority, but it is at a higherlevel and spread over a slightly more generous timescale: 50,000 a year for twoyears, then 30,000 a year for two years, totalling 160,000 over four years. A quarterof this grant is from the European VIVALDI programme. Funding is linked to a targetof achieving 1000 members by the

Details of many of the clubs can be found on the Carplus website www.carclubs.org.uk. Most UK clubs have been developed from the bottom up: that is, projects have . (Zipcar, Flexcar and City Carshare) had over 30,000 members. Communauto in Québec (Canada) has grown to over 3000 members in 7 years, and . members lost between the collapse .