Transcription

The Real Effects of FAS 166 and FAS 167Yiwei DouNew York Universityydou@stern.nyu.eduStephen RyanNew York Universitysryan@stern.nyu.eduBiqin XiePennsylvania State Universitybxx5@psu.eduApril 12, 2016We acknowledge helpful comments from Kai Du, Dan Givoly, Guojin Gong, Jed Neilson, HongQu, and participants of the Penn State Accounting Department brown-bag seminar.

AbstractWe examine the real effects of FAS 166 and FAS 167 on banks’ lending and securitizationactivities. Effective as of 2010, the two accounting standards tightened the accounting forsecuritizations and the consolidation of variable interest entities (VIEs), respectively. We provideevidence that banks’ consolidation of VIEs, mostly credit card securitization entities and assetbacked commercial paper conduits, under FAS 166/167 leads banks to reduce their supply of loans,as proxied by their loan-level mortgage approval rates. We find that the effects of banks’consolidated VIEs are significantly more negative than the effects of their unconsolidatedsecuritization entities on their mortgage approval rates, consistent with it being the consolidationof securitization entities rather than securitization per se that reduces banks’ loan supply. Moreover,we find that the differential lending effects of consolidated VIEs relative to unconsolidatedsecuritization entities are relatively stable during the post-FAS 166/167 period of 2010-2014,suggesting that the consolidation of VIEs under FAS 166/167 continues to affect lending five yearsafter the accounting standards came into effect. We also provide evidence that banks reduce theassets held by their consolidated VIEs after the effective date of FAS 166/167, with the reductionbeing larger for less capitalized banks. In contrast, we find that the issuance of asset-backedsecurities in Europe is relatively stable over the same time period, inconsistent with decreasinginvestor demand for asset-backed securities driving the declines in the U.S.

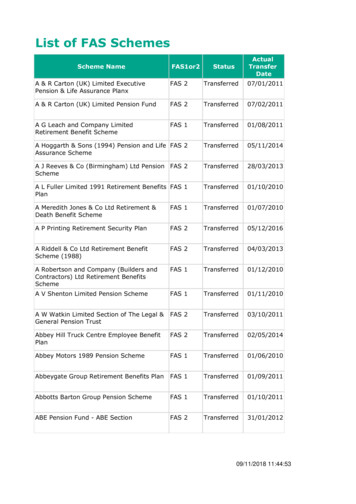

1. IntroductionWe examine the real effects of FAS 166 and FAS 167 on the lending and securitizationactivities of U.S. commercial bank holding companies (hereafter, “banks”). 1 Effective forDecember fiscal-year-end firms at the beginning of 2010, FAS 166 and FAS 167 tightened therules governing the accounting for securitizations and the consolidation of variable interest entities(VIEs), respectively. 2 Most of banks’ VIEs are special-purpose entities (SPEs) used insecuritization transactions to isolate the transferred assets from transferors, to contract with thevarious parties involved in the transactions (e.g., transferors, investors, servicers, and guarantors),and to distribute the cash flows generated by these assets to those parties. As of the end of 2010,27 publicly listed banks in our sample consolidated VIEs holding assets of 730 billion, 5.3% ofthe banking industry’s aggregate total assets.3 Of these mostly newly consolidated assets, about10% were held by asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) conduits and 80% by other types ofsecuritization entities, mostly credit card securitization entities. 4 Under the previous VIE1FAS 166, Accounting for Transfers of Financial Assets, amends FAS 140, Accounting for Transfers and Servicingof Financial Assets and Extinguishments of Liabilities. FAS 167, Amendments to FASB Interpretation No. 46(R),amends FIN 46(R), Consolidation of Variable Interest Entities, an Interpretation of ARB No. 51.2FIN 46(R) defines VIEs as entities that either (1) have insufficient equity investment at risk to permit the entity tofinance its activities without additional subordinated financial support from any parties or (2) have equity investorsthat do not have one or more of (a) the ability to make significant decisions relating to the entity’s operations throughvoting or similar rights, (b) the obligation to absorb the expected losses of the entity, and (c) the right to receive theexpected residual returns of the entity.3These numbers misstate the effect of newly consolidated VIEs under FAS 166/167 in two respects. First, the numbersoverstate the effect of FAS 166/167 to the (limited) extent that banks consolidated VIEs under FAS 140 and FIN46(R). Second, and conversely, because we hand collected the numbers from banks’ 2010 Form 10-K filings, whichare not available for 23 banks in our sample that are either private, or trade over-the-counter, or do not disclose theamount of assets held by their consolidated VIEs in their 10-K filings, the numbers understate the effect of FAS166/167. All banks were required to disclose the assets held by their consolidated VIEs in regulatory FR Y-9C filingsbeginning in 2011Q1. These filings indicate that these 23 banks consolidated VIEs holding assets of 46 billion in2011Q1.4An ABCP conduit is a SPE that finances medium- and long-term assets through the issuance of short-term (less than270 day maturity) ABCP. Institutional investors who want to hold safer assets, such as money market mutual funds,are the primary purchasers of ABCP. The inability of many ABCP conduits to roll over their ABCP in 2007Q3 playeda central role at the onset of the financial crisis.1

consolidation standard, FIN 46(R), banks generally did not consolidate ABCP conduits (exceptingsome multi-seller conduits) and credit card securitization entities, even when they bore much ofthe entities’ risk through the provision of credit or liquidity support or other means. FAS 166/167led to an increase in regulatory capital requirements, because bank regulators decided to includethe assets of all consolidated VIEs in banks’ total assets for calculating leverage ratios beginningin 2010Q1 and in their risk-weighted assets for calculating risk-weighted capital ratios either atthat time or with an optional two-quarter delay and two-quarter phase-in period (FDIC 2009).5Most financial firms that engage in securitizations opposed the FASB’s issuance of FAS166/167. For example, Mortgage Bankers Association suggested in its comment letter that theFASB conduct a study to assess the extent to which the standards would “discourage securitizationtransactions and thereby reduce the availability of credit” (Mortgage Bankers Association 2008, p.2). In contrast, banking regulators stated that the very large banks most affected by FAS 166/167and the associated bank regulatory decision will continue to have capital ratios that are“substantially in excess of regulatory minimums” and thus “will not encounter an immediate ornear-term need to decrease lending or raise substantial amounts of new capital for risk-basedcapital purposes” (FDIC 2009, p. 12).Empirical examination of the real effects of FAS 166/167 on banks’ lending andsecuritization activities can generate important policy implications, for at least three non-mutuallyexclusive reasons. First, many parties argue that excessive lending by banks and other financialfirms (or, equivalently, excessive borrowing by their counterparties) during the 2004-2006 creditThis decision includes both bank regulators’ (active) elimination of their prior exclusion for consolidated ABCPconduits (Acharya and Ryan 2016, Section 4.3) as well as regulators’ (passive and typical) decision to follow GAAPfor other newly consolidated VIEs under FAS 166/167. Securitizing banks lobbied regulators both to retain the ABCPexclusion and to mitigate the effect of FAS 166/167 for other types of securitizations in various ways (e.g., seeAmerican Bankers Association 2009).52

boom contributed significantly to the 2007-2009 financial crisis (e.g., Financial Crisis InquiryCommission 2011). Prior research provides evidence that securitization contributed to excesscredit supply prior to the financial crisis (Mian and Sufi 2009; Keys et al. 2010; Loutskina andStrahan 2009). Evidence that banks reduced their lending under FAS 166/167 and the associatedbank regulatory decision would be consistent with the prior non-consolidation of securitizationentities contributing to banks’ excessive lending during the boom. Second, motivated by thefinancial crisis and the view that higher capital requirements enhance financial stability, variousprovisions of Basel III and the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Actincrease bank capital requirements (Office of the Comptroller of the Currency 2013). Theimplications of these provisions for stability depend on whether and how higher capitalrequirements affect banks’ lending and securitization activities. Third, banks’ off-balance sheetsecuritization entities constitute part of the shadow banking system, i.e., financial intermediariesthat perform traditional banking functions but are not subject to safety and soundness regulation.By requiring banks to consolidate certain securitization entities, FAS 166/167 and the associatedbank regulatory decision effectively pulled these entities out of the shadow banking system. Hence,FAS 166/167 provides a powerful context to examine whether financial reporting can help reducethe risks of the shadow banking system.From the point of view of the individual, typically very large, banks that consolidatepreviously off-balance sheet securitization entities under FAS 166/167, these standards and theassociated bank regulatory decision constitute a plausibly exogenous increase in their capitalrequirements.6 In contrast, the standards do not have this effect on banks whose securitizationentities remain off-balance sheet under FAS 166/167 or the vast majority of banks that do not6Naturally, FAS 166/167 and the associated bank regulatory decision are endogenous to the overall financial system.3

engage in securitizations. This variation in the impact of FAS 166/167 within securitizing banksas well as across securitizing versus non-securitizing banks enables us to employ a difference-indifferences research design to examine whether higher capital requirements reduce bank lending.We measure the proportionate impact of FAS 166/167 on a bank’s total assets and thuscapital requirements by the ratio of the assets of the bank’s consolidated VIEs to the differencebetween the bank’s total assets and the assets of its consolidated VIEs. Following prior literature(e.g., Munnell et al. 1996; Loutskina and Strahan 2009; Xie 2016), we distinguish loan supplyfrom loan demand using banks’ decisions to approve or deny loan-level residential mortgageapplications available on the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) database. Compared toloan growth rates, the lending measure most commonly used in the prior literature, loan approvalrates are less affected by loan demand and thus better capture loan supply.We conduct the primary analysis using a randomly drawn stratified sample of 4,830,860residential mortgage applications from 913 sample banks in 2005-2014. Thirty five of these banksconsolidate at least one VIE in 2011. The aggregate total assets of these consolidating banks isover 11 trillion in 2011, about 75% of the total assets of the banking industry.We find that banks that consolidate proportionately more VIE assets under FAS 166/167subsequently experience significantly larger reductions in their loan approval rates. Thesereductions are economically significant; a bank consolidating VIEs holding assets equal to 10% ofits total assets on average experiences a sizeable 7.98% reduction in its loan approval rate by 2011that attenuates by a little less than a third to 5.39% by 2014. The effects of consolidated VIEs onmortgage approval rates are significantly more negative than the effects of unconsolidated VIEs(i.e., off-balance sheet securitization entities) on those rates, consistent with it being theconsolidation of securitization entities rather than securitization per se that reduces banks’ loan4

supply. More importantly, the differential lending effects of consolidated VIEs compared tounconsolidated VIEs are economically significant and relatively stable during the post-FAS166/167 period of 2010-2014; a bank consolidating VIEs holding assets equal to 10% of its totalassets on average experiences a sizeable 5% greater reduction in its loan approval rate comparedto a bank with unconsolidated VIEs holding assets equal to 10% of its total assets. This resultsuggests that the consolidation of VIEs under FAS 166/167 continues to affect lending five yearsafter the standards came into effect.We further find that the assets held by banks’ consolidated VIEs, in total and specificallytheir consolidated ABCP conduits and consolidated other securitization entities, decline from 2010to 2015 under FAS 166/167. Thus, the amortization of assets from pre-existing securitizations(including liquidations of securitization entities, as occurred for some banks’ ABCP conduits)exceeds the amount of newly securitized assets. Moreover, the rates of decline in the assets heldby all consolidated VIEs and by consolidated ABCP conduits are higher for less capitalized banks,consistent with capital constraints contributing to these declines. In contrast, the issuance of assetbacked securities in Europe is relatively stable during the same time period (in fact, ABCP issuancegrows rapidly during 2014-2015), inconsistent with decreasing investor demand for asset-backedsecurities driving the declines in the U.S.In summary, we provide evidence that the increase in regulatory capital requirementsresulting from banks’ consolidation of previously unconsolidated VIEs under FAS 166/167 andthe associated regulatory decision leads to reduced bank lending and securitization activities. Thisevidence contributes to the literature on the real effects of accounting in general and of FAS166/167 in particular, complementing prior findings about the impact of FAS 166/167 on banks’capital market variables such as risk and liquidity (Bonsall et al. 2015; Oz 2016), mortgage5

servicing (Bonsall et al. 2015), small business lending (Dou 2016), and loan liquidity (Forgioneand Zhao, 2015). This evidence also informs ongoing regulatory efforts to enhance financialsystem stability. It suggests that banks’ lower capital requirements in the pre-FAS 166/167 periodcontributed to banks’ excessive lending during the 2004-2006 credit boom. We emphasize that ourfindings that banks’ securitization activities decrease post-FAS 166/167 are subject to the caveatthat, due to lack of data, we have not employed a bank-level difference-in-differences researchdesign in this analysis. We are trying to acquire the data necessary to conduct such analysis.2. Background Information, Related Literature, and Hypothesis Development2.1 Background InformationFAS 166 and FAS 167 amend FAS 140 and FIN 46(R), respectively. Under these priorstandards, securitizing banks typically accounted for securitizations as sales and did notconsolidate the securitization entities. In this case, banks recognized only their retained interestsin these entities. For most types of securitizations (some multi-seller ABCP securitizations beingan exception), banks typically structured the securitization entities to meet the three conditions fora qualifying special-purpose entity (QSPE) in paragraph 35 of FAS 140. This paragraph specifiesthat QSPEs are demonstrably distinct from their transferors, have significantly limited permittedactivities, and are largely passive. Paragraph 46 of FAS 140 exempted QSPEs from consolidationby their transferors. Paragraph 4d of FIN 46(R) exempted QSPEs from consolidation by otherparties that lack the unilateral power to liquidate the entities or to change them to not be QSPEs.FIN 46(R) required firms to consolidate (non-QSPE) VIEs in which they bore more than50% of the expected risks and rewards. This quantitative approach led banks to engage in brightline structuring to avoid consolidation of VIEs, such as selling first-loss interests that were justlarge enough to bear 50% of the entities’ expected risks and rewards according to banks’ models6

(“expected loss notes”) to risk-tolerant investors (Bens and Monahan 2008; Acharya and Ryan2016, Section 4.3).Under FAS 140 and FIN 46(R), banks could bear essentially all of the risk of the assetsheld by QSPEs and much of the risk of assets held by other VIEs while not consolidating theentities. For example, sponsoring banks bore almost all the losses of their (often non-consolidated)ABCP conduits during the 2007-2009 financial crisis through the provision of liquidity support(Acharya et al. 2013).Both prior to and after FAS 166/167 and the associated regulatory decision, banks’ totaland risk-weighted assets exclude the assets of their non-consolidated VIEs. In addition, prior toFAS 166/167 banks’ risk-weighted assets excluded the assets of ABCP conduits consolidatedunder FIN 46(R) (the ABCP exclusion). Although regulators generally required banks to holdsome capital for their risk-absorbing retained interests in non-consolidated VIEs, nonconsolidation often lowered banks’ capital requirements. Such “regulatory arbitrage” was aprimary motivation for banks to structure securitizations to avoid consolidation of the entities(Acharya et al. 2013; Acharya and Ryan 2016, Section 4.3).The 2007-2009 financial crisis revealed the sizable credit and liquidity risks that banksretained in their non-consolidated VIEs (e.g., Financial Times 2009). Responding to concerns ofinvestors, bank regulators, the SEC, the President’s Working Group on Financial Markets, andmany others that banks’ financial reports did not adequately portray these risks, in June 2009 theFASB issued FAS 166 and FAS 167 (FASB 2009). FAS 166 eliminates QSPEs as a category ofspecial purpose entities exempt from consolidation.7 FAS 167, whose scope includes virtually all7Essentially a consequence of its elimination of QSPEs, FAS 166 also eliminates the permission in paragraph 13 ofFAS 140 of the functional equivalent of sale accounting for guaranteed mortgage securitizations involving QSPEs.7

entities that previously had been deemed QSPEs, requires banks and other firms to consolidateVIEs over which they have “the power to direct the activities that most significantly impact theentity’s economic performance” as well as the “obligation to absorb losses of the entity that couldpotentially be significant”. This qualitative approach to VIE consolidation contrasts with FIN46(R)’s quantitative approach described above. Collectively, FAS 166’s elimination of QSPEs andFAS 167’s qualitative approach caused banks to consolidate VIEs (mostly credit cardsecuritization entities and ABCP conduits) holding 730 billion of assets in 2010, equal to 5.3%of the aggregate total assets of the banking industry.In December 2009, bank regulators issued a final rule that includes the assets held by allof banks’ VIEs consolidated under FAS 166/167 (including previously excluded consolidatedABCP conduits) in banks’ total assets for calculating leverage ratios and in their risk-weightedassets for calculating risk-based capital ratios (FDIC 2009). This rule provided banks with theoption to delay the effects on their risk-based capital ratios for two quarters followed by twoquarter phase-in.2.2 Related ResearchSeveral contemporaneous working papers provide evidence that FAS 166/167 hassignificant effects. Two studies examine different effects of FAS 166/167 from the effects onlending and securitization that we examine. Oz (2016) finds that FAS 166/167 reduce twomeasures of securitizing banks’ information asymmetry (equity bid-ask spread and Amihud’smeasure of illiquidity/price impact of trade). Bonsall et al. (2015) finds that FAS 166/167 improvethe equity risk-relevance of securitizations, with only securitizations accorded on-balance sheettreatment (i.e., accounted for as secured borrowings with the securitization entities consolidated)8

being risk-relevant in the post-FAS 166/167 period. They also find that banks increasingly sellmortgage servicing rights to third parties post-FAS 166/167.Two studies examine effects of FAS 166/167 on bank lending. Forgione and Zhao (2015)examine the effects of FAS 166/167 on banks’ lending and loan liquidity. Our study differs fromtheirs in two significant and probably related ways. First, we use banks’ loan-level mortgageapproval decisions to separate loan supply from loan demand, whereas Forgione and Zhao (2015)do not distinguish loan supply from loan demand. Second, we find that FAS 166/167 are associatedwith reduced bank lending, whereas Forgione and Zhao (2015) find that the two accountingstandards do not affect lending.Dou (2016) examines the effect of FAS 166/167 on banks’ small business lending. Becausebanks rarely securitize small business loans, FAS 166/167 only affects small business lendingthrough the accounting for securitizations of other types of loans and thus on banks’ regulatorycapital adequacy. Dou (2016) finds that banks that consolidate securitization entities under FAS166/167 reduce small business lending relative to banks that do not consolidate any entity but lendin the same county. The reduction is larger for banks that are less capitalized, that consolidatesecuritization entities holding more assets, and that have less ability to raise capital.Our examination of banks’ mortgage lending at the loan level and Dou’s (2016)examination of banks’ small business lending exhibit distinct relative strengths. The biggestrelative strengths of our setting are the ability to distinguish loan supply from loan demand byexamining loan-level mortgage approval decisions using HMDA data as well as the economicallyhighly significant volume of mortgage lending and securitization. The biggest relative strengths ofDou’s (2016) setting are the ability to hold the (nonexistent) securitization market for smallbusiness loans constant over time in order to identify the effect of FAS 166/167 as well as the9

ability to develop well-matched treatment and control samples subject to the same county-leveleconomic conditions.2.3 Hypothesis Development2.3.1 The Effect of FAS 166/167 on Bank LendingIt is not a priori clear whether consolidation of previously unconsolidated VIEs under FAS166/167 should cause banks to reduce lending. On one hand, two non-mutually exclusive reasonssuggest this consolidation likely causes banks to reduce lending. First, prior research shows thatbanks engage in regulatory arbitrage to mitigate the impact of regulatory capital requirements ontheir activities, including structuring securitizations to be off-balance sheet (e.g., Calomiris andMason 2004). Hence, consolidation of VIEs under FAS 166/167 may lead banks to allocate someof their preexisting regulatory capital for the newly consolidated entities’ assets, and it may reducecapital by requiring banks to accrue allowances for loan losses for the portion of these assets thatare loans (FDIC 2009). Second, banks often maintain regulatory capital ratios around target levelswell above the well-capitalized threshold (Berger et al. 2008; Gropp and Heider 2010). Followinga shock to their capital ratios, banks typically adjust the ratios back to the target ratios by adjustingthe amounts of their assets and liabilities, not the amount of equity (Adrian and Shin 2011; Lauxand Rauter 2015).On the other hand, three non-mutually exclusive reasons suggest this consolidation isunlikely to affect bank lending. First, consolidation of VIEs does not affect whether bankseconomically bear the entities’ risk and rewards and so should not affect their ability to supplyloans. Second, and relatedly, rating agencies and investors appear to treat off-balance sheetsecuritizations in which transferors provide recourse as on-balance sheet (Barth et al. 2012), soconsolidating those entities may not affect banks’ credit ratings or cost of capital. Third, as noted10

above banks often maintain regulatory capital well above the well-capitalized threshold, so theadditional required capital for newly consolidated VIEs may not render regulatory capitalconstraints binding and thereby reduce banks’ ability to supply loans. As discussed in theintroduction, this is the stated belief of bank regulators (FDIC 2009). Consistent with this belief,only one bank elected to exercise the option to delay/phase-in the effect of FAS 166/167 on riskbased capital ratios.Overall, we expect the reasons for FAS 166/167 to have no effect on banks’ lending not tofully dominate the reasons for the standards to decrease lending. However, we also expect FAS166/167’s effect on lending to decrease over time as banks take steps to mitigate the adverse impactof FAS 166/167 on their capital adequacy, such as reducing the assets held by consolidated VIEsand raising capital. Hence, we state the following hypothesis:H1: FAS 166/167 are associated with reduced bank lending, and this effect decreases overtime.2.3.2 The Effect of FAS 166/167 on Securitization Activities Involving Newly Consolidated VIEsTo the extent that any reductions in bank lending (posited in H1) do not fully offset banks’increased capital requirements from newly consolidated VIEs under FAS 166/167, banks mayreduce their securitization activities involving these entities. It is again not a priori clear, however,whether this should be the case. On one hand, the increased regulatory capital requirements mayincrease banks’ cost of raising funds through securitization and thereby dissuade banks fromextending loans intended to be securitized through newly consolidated entities. On the other hand,even with such consolidation, the cost of raising funds through securitization likely is lower thanthe cost of banks’ alternative sources of (unsecured) debt financing, leading them to maintain theirsecuritization activities. Moreover, securitization is an important funding source for many of the11

largest banks, and bank regulators stress the importance of banks raising funds from diversifiedsources to mitigate liquidity risk (FDIC 2009, 2015). Hence, banks may continue to usesecuritization to raise funds to appear more liquid (Opstal 2013).If banks do reduce their securitization activities involving newly consolidated VIEs underFAS 166/167, then the follow-on question arises whether less capitalized banks more aggressivelyreduce these activities. Yet again the answer is a priori unclear. On one hand, the likelihood ofviolating regulatory capital requirements due to consolidating VIEs holding a given amount ofassets is greater for less capitalized banks. On the other hand, the reduction of the cost of fundsfrom securitization compared to alternative sources of debt financing likely is greater for lesscapitalized banks. In particular, the cost of funds from securitization, a secured form of financing,should not depend much on banks’ capitalization, whereas the cost of unsecured financing shouldbe higher for less capitalized banks.Overall, we expect the reasons for FAS 166/167 to have no effect on banks’ securitizationactivities not to fully dominate the reasons for the standards to reduce these activities, particularlyfor less capitalized banks. This expectation is supported by prior research that shows that banksengage in off-balance sheet securitizations in part to reduce their regulatory capital requirements.For example, Acharya et al. (2013) provides evidence that such regulatory arbitrage motivatedbanks’ ABCP conduit securitizations prior to the 2007-2009 financial crisis. Given regulators’decision to include the assets of all consolidated VIEs in banks’ total and risk-weighted assets forcalculating regulatory capital ratios, banks’ consolidation of certain types of previouslyunconsolidated securitization entities under FAS 166/167 eliminates this benefit for thosesecuritizations (FDIC 2009). We expect the removal of this benefit leads banks to reduce the assets12

held by their newly consolidated securitization entities under FAS 166/167. Hence, we state thefollowing one-tailed hypothesis in the alternative form:H2: Banks reduce the assets held by their newly consolidated VIEs under FAS 166/167over time, with the rate of reduction being higher for less capitalized banks.To the extent that the relations posited in H2 obtain, we expect these relations to be weakerfor types of securitizations that more strongly reduce banks’ funding cost compared to alternativesources of debt financing. The extent of this reduction naturally depends on market demand, whichdata on asset-backed securities outstanding from SIFMA suggest varies considerably acrossdifferent types of securitizations in the post-financial crisis period. Investors appear to haveaccepted certain types of asset-backed securities more than others in their search for yield in a lowinterest rate environment (Financial Times 2012).Our ability to examine different types of securitizations is limited by the fact that banks’regulatory FR Y-9C filings, our source of bank financial data, only report the assets held by twocategories of consolidated securitization VIEs: ABCP conduits and other securitization entities.As noted previously, credit card securitization entities hold the bulk of the assets held by otherconsolidated securitization entities. According to SIFMA, ABCP outstanding fell almostmonotonically from 1,191 billion in July 2007 on the cusp of the financial crisis to 227 billionin May 2015, consistent with market demand being insufficient to stem the decline.8 Similarly,credit card receivable–backed securities outstanding fell from 325 billion at the end of 2007 to 128 billion at the end of 2012, remaining fairly flat since then.9 These statistics suggest that ttp://www.sifma.org/research/statistics.aspx13

should hold both for ABCP conduits and for other securitization entities. Hence, we state thefollowing special cases of H2 as one-tailed hypothesis in the alternative form:H2–ABCP: Banks reduce the assets held by their newly consolidated ABCP conduitsunder FAS 166/167 over time, with the rate of reduction being higher for less capitalizedbank

10% were held by asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) conduits and 80% by other types of securitization entities, mostly credit card securitization entities. 4 Under the previous VIE 1 FAS 166, Accounting for Transfers of Financial Assets, amends FAS 140, Accounting for Transfers and Servicing