Transcription

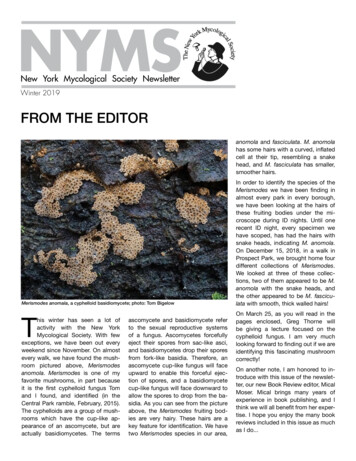

NYMSNew York Mycological Society NewsletterWinter 2019from the Editoranomola and fasciculata. M. anomolahas some hairs with a curved, inflatedcell at their tip, resembling a snakehead, and M. fasciculata has smaller,smoother hairs.Merismodes anomala, a cyphelloid basidiomycete; photo: Tom BigelowThis winter has seen a lot ofactivity with the New YorkMycological Society. With fewexceptions, we have been out everyweekend since November. On almostevery walk, we have found the mushroom pictured above, Merismodesanomola. Merismodes is one of myfavorite mushrooms, in part becauseit is the first cyphelloid fungus Tomand I found, and identified (in theCentral Park ramble, February, 2015).The cyphelloids are a group of mushrooms which have the cup-like appearance of an ascomycete, but areactually basidiomycetes. The termsascomycete and basidiomycete referto the sexual reproductive systemsof a fungus. Ascomycetes forcefullyeject their spores from sac-like asci,and basidiomycetes drop their sporesfrom fork-like basidia. Therefore, anascomycete cup-like fungus will faceupward to enable this forceful ejection of spores, and a basidiomycetecup-like fungus will face downward toallow the spores to drop from the basidia. As you can see from the pictureabove, the Merismodes fruiting bodies are very hairy. These hairs are akey feature for identification. We havetwo Merismodes species in our area,In order to identify the species of theMerismodes we have been finding inalmost every park in every borough,we have been looking at the hairs ofthese fruiting bodies under the microscope during ID nights. Until onerecent ID night, every specimen wehave scoped, has had the hairs withsnake heads, indicating M. anomola.On December 15, 2018, in a walk inProspect Park, we brought home fourdifferent collections of Merismodes.We looked at three of these collections, two of them appeared to be M.anomola with the snake heads, andthe other appeared to be M. fasciculata with smooth, thick walled hairs!On March 25, as you will read in thepages enclosed, Greg Thorne willbe giving a lecture focused on thecyphelloid fungus. I am very muchlooking forward to finding out if we areidentifying this fascinating mushroomcorrectly!On another note, I am honored to introduce with this issue of the newsletter, our new Book Review editor, MicalMoser. Mical brings many years ofexperience in book publishing, and Ithink we will all benefit from her expertise. I hope you enjoy the many bookreviews included in this issue as muchas I do.

CONTENTSMicrobia: A Journey into the Unseen World Around You byEugenia Bone reviewed by Mical Moser.5How to Change Your Mind by Michael Pollan reviewed byLeah Krauss.6Green-Wood Cemetery: A Place for the Dead That Teems with Lifeby Sigrid Jakob .10The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility ofLife in Capitalist Ruins reviewed by William May.12Organic Mushroom Farming and Mycoremediation byThe Mushroom Fan Club by Elise Gravel reviewed byMac Crenson.14Mushrooms: A Natural and Cultural History by Nicholas P. Moneyreviewed by Matt Gardner.14Organic Mushroom Farming and Mycoremediation by Tradd Cotterreviewed by Craig Trester .15Upcoming EventsJuly 26 – 28: Chanterelle Weekend, Green Mountains, VTOctober 4 – 6: Catskill WeekendEagle Hill Workshops, 2019May 19 – 25: Lichens and Lichen Ecology - Troy McMullinMay 26 – Jun 1: Old-growth Forest Lichens and Allied Fungi, with a Focuson Calicioids - Steven Selva and Troy McMullinMay 26 – Jun 1: Introduction to Bryophytes and Lichens - Fred OldayJun 16 – 22: Independent Study: Topics in Fungal Biology - Donald PfisterJul 28 – Aug 3: Mushroom Identification for New Mycophiles: Foraging forEdible and Medicinal Mushrooms - Greg Marley and Michaeline MulveyAug 11 – 17: Crustose Lichens, Accessory Fungi, and Symbiotic Transitions Toby SpribilleAug 11 – 17: Lichens, Biofilms, and Stone - Judy Jacob and Michaela SchmullAug 18 – 24: Mushroom Microscopy: An Exploration of the IntricateMicroscopic World of Mushrooms - David Porter and Michaeline MulveySep 27 - 29: Fall Maine Mushrooms - David Porter and Michaeline MulveyForaysAugust 1 – 4: 2019 NEMF Samuel Ristich Foray; 43rd Annual Foray of theNortheast Mycological Federation, Lock Haven University, PAAugust 8 – 11: 2019 NAMA Annual Foray, Paul Smiths, New YorkNYMS NewsletterEditor—Juniper PerlisCopy editor—Ethan CrensonDesign—Ethan CrensonA quarterly publication of theNew York Mycological Society,distributed to its members.President—Tom BigelowVice President—Dennis AitaSecretary—Paul SadowskiTreasurer—Kay SpurlockWalks Coordinator—Dennis AitaLecture Coordinator—Tom BigelowStudy Group—Paul SadowskiArchivist—Ralph CoxReviews Editor—Mical MoserWebmaster—Ethan Crensonwww.newyorkmyc.orgArticles should be sent to:Juniper Perlis713 Classon Ave, Apt 505Brooklyn, NY 11238juniperperlis@yahoo.com347.743.9452Membership inquiries:Kay Spurlock—TreasurerNew York Mycological SocietyP.O. Box 1162 Stuyvesant Sta.New York, NY 10009KSpur98@aol.comAddress corrections:Paul Sadowski205 E. 94 St., #9New York, NY 10128-3780pabloski1@verizon.netAll statements and opinions written in thisnewsletter belong solely to the individualauthor and in no way represent or reflectthe opinions or policies of the New YorkMycological Society. To receive thispublication electronically contact PaulSadowski at: pabloski1@verizon.netArchive copies of the newsletter areavailable in the Resources section of ourwebsite.Submissions for the next issue of theNYMS newsletter must reach the editorby June 15, 2018. Various formats are acceptable for manuscripts. Addressquestions to Juniper Perlis, editor.See above for addresses.

A Message from our Reviews EditorRemember!For three years now I’ve been a member of the New York Mycological Society.Something that’s become clear is this: as a community, our knowledge is only asgood as our resources. While there are many excellent digital resources availableto mycophiles, I have always been charmed by how much fungal knowledgeis bound up in books (that is real books; physical books). My professional liferevolves around books, and you can always count on me to cheer on the goodones. A number of months ago, I offered to our newsletter editor, Juniper Perlis,that it would be nice to have more book reviews, and I could help shepherd themalong. If any of you are interested in writing reviews, or if you have written a bookthat you’d like reviewed or noted, please let me know.–Mical MoserReviews Editormicalmoser@me.comStay responsibly in touch with us.If your telephone number, mailingor email address changes, pleasecontact Paul Sadowski, Secretarywith your new information. On yourmembership form, please considergoing paperless when it comes toreceiving these newsletters. Newsletters sent via email (PDF file format) are in color, have live web links,help us contain costs, and usefewer natural resources!Chanterelle Weekend 2019July 26-28, The Green Mountains of Southern VermontAfter two years of organizing the splendid NYMS Chanterelle Weekend, EthanCrenson is taking a respite, and Dorota Kolodziejczyk and Jason Duval willorganize, with support offered from Laura Biscotto and Adrienne Haeberle.As we send this issue of the newsletter to press, the details of the house rentaland other specifics are still in the works. However the weekend dates are setfor July 26 – 28th, the weekend before the NEMF Samuel Ristich Foray.A deposit of 50.00 should be submitted along with the registration form at theback of this newsletter issue before June 1. Please make checks out to NYMS.Mail both the form and the check to:Laura Biscotto9 Stanton St, Apt 2CNew York, NY 10002212 677 3060labisco3@gmail.comNYMS walks policy: We meet whenpublic transportation arrives. Checkthe walks schedule for other transportation notes. Walks last 5-6 hoursand are of moderate difficulty exceptwhere noted. Bring your lunch,water, knife, a whistle (in case youget lost or injured), and a basket formushrooms. Please let a walk leaderknow if you are going to leave early.Leaders have discretion to cancelwalks in case of rain or very dryconditions. Be sure to check youremail or contact the walk leaderbefore a walk to see if it has beencanceled for some reason.Nonmembers’ attendance is 5 foran individual and 10 for a family.We ask that members refrain fromvisiting walk sites two weeks priorto the walk.Warning: Many mushrooms aretoxic. Neither the Society nor individual members are responsible forthe identification or edibility of anyfungus.Paul Sadowski with Leccinum and wine at the 2018 Chanterelle Weekend in Stratton, VTphoto by Vicky Tarttar3

2019 Emil Lang Lecture SeriesThe NYMS Emil Lang Lectures for 2019 will be held on Monday nights, from 6:00-8:00,at the Central Park Arsenal. The entrance is just off 5th Ave. at 64th St.The Arsenal, Central Park830 5th Ave., Rm 318 (@ 64th St.)New York, NY 10065The lectures are free and open to the public.February 25th: Else Vellinga, “Fungal Conservation”Else VellingaElse Vellinga is a mycologist who is interested in naming and classifying mushroomspecies in California and beyond, especially Parasol mushrooms. She has described22 species as new for California, and most recently worked at the herbaria at Universityof California at Berkeley and San Francisco State University for the Macrofungi andMicrofungi Collections Digitization projects. She got her training at the NationalHerbarium in the Netherlands, and her PhD at the University of Leiden, also in theNetherlands. The main motivation for her taxonomic work is that it lays the basis forefforts to include mushroom species in nature management and conservation plans.She has proposed a number of Californian and Hawaiian species for the IUCN globaldatabase of endangered species. She tries to keep current with the mushroom literature.And lastly, Else is an avid knitter and likes to use mushroom dyed yarn for her creations.She lives with her two cats in Berkeley, California.March 25th: Greg Thorn, “Explorations of Cyphelloid Fungi (and other WeeMushrooms) in the Molecular Age”Greg ThornGreg Thorn grew up in London, Ontario and became interested in natural historythrough the family garden, long summer vacations, and the local Field Naturalists group.Six summers as a naturalist in Algonquin Park built on this and introduced him to theworld of mushrooms and other fungi. Mushroom forays of the Mycological Society ofToronto and NAMA were an important part of his training, where he met and learnedfrom the likes of Gary Lincoff, Ron Petersen, Alex Smith, and many more. Writing thechecklist of Algonquin Park macrofungi led Thorn to consult experts from Richard Korfto Jim Ginns and Scott Redhead, all of whom encouraged him to further studies offungi. His graduate studies were at the University of Guelph (with George Barron) andthe University of Toronto (with David Malloch), followed by positions in Japan, Michigan,Indiana, Wyoming, and finally back to London as a faculty member in the Departmentof Biology, University of Western Ontario. Thorn’s research is focused on the impact ofdisturbance on the diversity of mushroom fungi, and systematics of mushroom fungigenerally.April 29th: Rod Tulloss, “Amanita with a Hand Lens and the Naked Eye:Communicating About Unfamiliar Finds Using the Seven Sections Recognizedby Dr. Cornelis Bas”Rod TullossRod Tulloss has specialized in Amanitaceae for 42 years, having been mentored bythe late Dr. Cornelis Bas (Leiden). His research is available through an expanding,open-access, on-line monograph, “Studies in the Amanitaceae” founded by him andco-edited with Dr. Zhu L. Yang (Kunming). The site treats over 1,050 taxa and includesa peer-reviewed e-journal (“Amanitaceae”) restricted to research associated with theherbarium and/or its staff. He is currently working on Amanita sect. Vaginatae for NorthAmerica; the Boston Harbor Islands fungal inventory; providing support for individualsand clubs working on Amanita sequences via North American Mycoflora grants; providing interactions and teaching moments on mushroomobserver.org and on the Amanitaof North America facebook group, etc. He maintains an extensive private herbarium ofworld Amanitaceae. Visit his website: http://www.amanitaceae.orgMay 20th: Nova Patch, “Urban Lichens of New York City”Nova Patch is an amateur lichenologist focusing on the urban lichens of NYC and curator of the open data project Lichens of New York City on iNaturalist. They are a regularspeaker on diverse topics ranging from lichenology to emoji engineering, hold a botanycertificate from the New York Botanical Garden, and are a Brooklyn-residing member ofthe New York Mycological Society. Nova will lead a city lichen walk the weekend following their talk.Nova Patch4

MicrobiaA Journey into the Unseen World Around YouBy Eugenia Bone2018 Hardcover 272 pp. Rodale 9781623367350 25.99Book Review by Mical Moserhyper-competentyoung adults andequallyimpressivemicroscopicorganisms.The newest book from past NYMSpresident, Eugenia Bone, is Microbia:A Journey into the Unseen WorldAround You (Rodale). It is to bacteriawhat her last book, Mycophilia, wasto mushrooms: a readable, delightful,fact-filled tour. (You know Mycophilia,right? If not, it’s time to take a personalday and catch up on your reading.)Bone always immerses herself in hersubject and with Microbia, she goesso far as to take science classes atColumbia so that we don’t have to.The world that emerges is filled withPreviously, “fungus”was the answer to anyquestion I ever asked.But Bone has lifted aveil. What’s the REALapex predator onthe planet? Bacteria.What digests mostof the food youeat? Bacteria. Whatprotects your earsfrominfections?Bacteria.What’sall over everythingand let’s just acceptit? Yes, indeed, theanswer is bacteria.And if the answer isn’tbacteria, it’s probablybacterial-fungalinteraction. As inwhy, when antibioticscure what ails you,does another malaisesometimespopup? The answer (as you’ve probablyguessed) is that you’ve thrown off theequilibrium of your body’s bacterialfungal interaction.I don’t want to give you the impressionthat Bone’s book is all about infections,disease, and laboratories. To thecontrary. Her subtitle could have been“How I Stopped Worrying and Learnedto Love Bacteria.” It’s a fascinating,feel-good celebration of germs. Oneof the great joys of reading Microbiawas that it helped me recognize thedifference between cleanliness andsterility. Bacteria is a necessary andhealthy part of a clean environment;sterility is not. You may want sterility inyour sealed jar of mushroom duxelles(for which you can go to anotherof Bone’s books, Well-Preserved:Recipes and Techniques for Putting upSmall Batches of Seasonal Food), andyou may want sterility on your surgeon’sscalpel, but bacteria are a necessarypart of our living environment. We eatit in yoghurt. We swap it with all of ourloved ones and friends. We share itwith a community of 10 million NewYorkers and countless tourists who’vealso put their hands on our subwaycar pole. Our skin is amazingly adeptat maintaining a correct bacterialbalance throughout. The trick withbacteria isn’t to get rid of it, but to helpbacteria maintain the right equilibriumand stay in the right place (all E. coliback to the intestine please!). So whileyou read Bone’s book, smell the ink,touch the pages, and while you’re atit, go ahead and enjoy a cheese plate!Kiss everyone on both cheeks à lafrançaise! Clink glasses with strangersat the table! Santé!Eugenia Bone; photo Huger Foote5

How to Change Your Mindby Michael Pollan2018 Hardcover 480 pp. Penguin 9781594204227Book Review by Leah KraussMichael Pollan offers threeanecdotes to explain how hefound himself writing a bookon psychedelics. First, in 2010, Pollancame across a front-page story fromthe New York Times, “HallucinogensHave Doctors Tuning In Again,”which reported that Johns Hopkins,UCLA, and New York University weredosing terminally ill cancer patientswith psilocybin (the psycho-activecompound in “magic mushrooms”)to alleviate “existential distress”among the dying. Pollan wonderedat the logic of these studies and wassurprised to read that “many of thevolunteers reported that over thecourse of a single guided psychedelic‘journey’ they reconceived howthey viewed their cancer and theprospect of dying. Several of themsaid they had lost their fear of deathcompletely” (8). Sometime later, hefound himself at a dinner party wherea psychologist mentioned using LSDas a means to consider children’sperceptions of the world. Whenasked if she would ever publish herobservations, she dismissed Pollanas politically naive. As a professional,she was not going to publicly discusstaking psychoactive drugs. Andfinally, post dinner party, Pollanrecollected an unopened email from2006, a study in Psychopharmacologyfrom Johns Hopkins, “PsilocybinCan Occasion Mystical-TypeExperiences Having Substantial andSustained Personal Meaning andSpiritual Significance” (10). Thisstudy, which Pollan attributes tothe beginning of a “renaissance ofpsychedelic research,” is the firstof many studies focused not on thespecific pharmacological effect ofa drug, but rather on “the kind of6mental experience it occasions.” Andso, a popular writer best known forwriting about human culture and food,embarks on an in-depth exploration oftwo Schedule One drugs, Psilocybinand LSD. In focusing on the socialhistory and present research ofthese particular compounds, Pollannotably sidesteps the growingpervasiveness of ayahuasca rituals inthe United States and the popularityof MDMA, an amphetamine oftenused in psychedelic therapy, anda compound with its own body ofresearch and medical trials. Pollan’sbook, at four hundred plus pages, isno less thorough for these omissions.Pollan writes with a gentle butinterrogative curiosity. His book isstructured first around the historiesof scientific interest in psilocybinand LSD, followed by Pollan’s ownexquisitely described psychedelic“journeys” facilitated by undergroundguides. (He was ineligible for theuniversity-based studies). He thenwades through tidal pools of neuroimaging research and offers a basicread of what happens to the mind onpsychedelics. The book winds downwith evocative stories of clinical trialsof the dying, the addicted, and thedepressed. For the purposes of thisreview, I will glance along the surfaceof the history and dip a toe into theneurobiology. The book is in factunwieldy in the various ideas it putsforward and perhaps most appealingin its patient testimonials, which Ihave not included here out of concernfor the length of this review.Pollan places considerable attention on the story of psychedelicsand the medical establishment overthe second half of the 21st century.His chapter on LSD, in particular,diligently and with deceptive ease,charts a complicated debate acrossthe Coastal United States, Saskatchewan, other parts of Canada, andparts of Europe. LSD was synthesizedin 1938 by Swiss Chemist AlbertHoffman, and accidentally ingestedby him for the first time in 1943, fiveyears later. He self-dosed epically,in what Pollan describes as the first“bad trip” in recorded history. Uncertain of how to make sense of theseeming madness and transcendenceof that self-dosing, Hoffman wascertain that the chemical could be putto medical use. Sandoz, the pharmaceutical company that employedHoffman, distributed LSD freely to anyscientific study that would documentfindings. Many labs and enterprising individuals rose to the challenge.The drug was initially conceived ofas a psychotomimetic (a replicatorof psychosis), then as a psycholytic,a truth serum of sorts, and finally asits own distinct category of “mindmanifesting” (the meaning of “psychedelic”) experience. At each stage,scientists hypothesized the chemicalaction on the mind and at each stage,it seemed close but not representative of what was happening in theexperience. One example of this phenomena took place in 1953, in a study

put forward by Humfrey Osmandand Abrahm Hoffer at their clinic inSaskatchewan, in which the cliniciansoffered volunteers a high dose of LSDas a mimetic of intense withdrawalfrom alcohol. Pollan writes, “Here wasan arresting application of the psychotomimetic paradigm: use a singlehigh-dose LSD session to induce anepisode of madness in an alcoholicthat would simulate delirium tremens,shocking the patient into sobriety.”For the following ten years, “Osmandand Hoffer tested this hypothesis onmore than seven hundred alcoholics,and in roughly half the cases, theyreported, the treatment worked: thevolunteers got sober and remainedso for at least several months. Notonly was the new approach moreeffective than other therapies, but itsuggested a whole new way to thinkabout psychopharmacology. ‘Fromthe first, Hoffer wrote, ‘we considerednot the chemical, but the experienceas a key factor in therapy.’ This novelidea would become a central tenet ofpsychedelic therapy” (149). In spite ofthe treatment’s success, in catalogingtheir data, the therapists noted a highdiscrepancy between the subjectiveexperience of LSD and the horrorsof DTs. In the reports “‘psychoticchanges’ - hallucinations, paranoia,anxiety – sometimes occurred, butthere were also descriptions of, say,‘a transcendental feeling of beingunited with the world,’ one of themost common feelings reported.Rather than madness, most volunteers described sensations such asa new ability ‘to see oneself objectively’; ‘enhancement in the sensoryfields’” etc. “In spite of the powerfulexpectancy effect, symptoms thatlooked nothing like those of insanitywere busting through the researchers’preconceptions” (150).Regardless of the theoretical modelunderpinning the treatment, “by theend of the decade, LSD was widelyregarded in North America as amiracle cure for alcohol addiction”(151). As this episode illustrates, psychedelics shifted the mental healthconversation back toward patients’interior experience, rather than onwhat could be externally observed.“The emphasis on what subjects feltrepresented a major break with theprevailing ideas of behaviorism inpsychology, in which only observableand measurable outcomes countedand subjective experience wasdeemed irrelevant” (149). Additionally, the realization that “LSD affectedconsciousness at such infinitesimaldoses” “helped to advance the newfield of neurochemistry in the 1950s,leading to the development of theSSRI antidepressants” (293). StephenRoss, an addiction researcher atBellevue, later shared with Pollan hisastonishment at learning this historyafter his formal education, “‘Beginning in the early fifties, psychedelicshad been used to treat a whole hostof conditions’ including addiction,depression, obsessive-compulsivedisorder, schizophrenia, autism, andend-of-life anxiety. There had beenforty thousand research participantsand more than a thousand clinicalpapers! Some of the best mindsin psychiatry had seriously studiedthese compounds in therapeuticmodels, with government funding.’But after the culture and the psychiatric establishment turned againstpsychedelics in the mid-1960s, an entire body of knowledge was effectivelyerased from the field” (142).One of the features of present psychedelic medicine that Pollan drawsattention to is that the substance, beit psilocybin or LSD, is not thought tobe sufficient to produce the desiredresults. Regardless of how people arealtered by these drugs recreationally,the most efficacious studies of thepast, and essentially all researchtrials under discussion, are preoccupied with a therapeutic relationshipin addition to the application of adrug. Michael Pollan follows thebreadcrumbs to the original medicalapplication of “Set and Setting.”A term attributed to Timothy Leary,“Set and Setting” was conceptuallyapplied prior to Leary’s work, notablyby underground guide, Al Hubbard,in collaboration with Osmond andHoffer at their clinic in Saskatchewan.In the 1950s, psychedelic therapy“typically involved a single, high-dosesession, usually of LSD, that tookplace in comfortable surroundings,the subject stretched out on a couch,with a therapist (or two) in attendance” quietly allowing the journeyto unfold. “To eliminate distractionsand encourage an inward journey,music [was] played and the subjectusually [wore] eyeshades. The goalwas to create the conditions for aspiritual epiphany – what amountedto a conversion experience” (163).Participants were given a set of “flightinstructions,” that encouraged themto go deeper into the experience withassurances that guides would serveas “ground control” for the durationof the “trip.” Guidance of this sortshaped the larger contours of thepsychedelic journey, with doctorsencouraging self-transcendence (anineffable experience highly correlatedwith long-lasting results). Clinicianas spiritual guide does appear to bean essential part of past and present“trip treatment.”Pollan shares a few quotes by Dr.Sydney Cohen, from an essay published by Harper’s in 1965, where Cohen writes on the potential of psychedelics for the dying. Cohen invokestreatment with LSD as “‘therapy byself-transcendence.’ The premisebehind the approach was that ourfear of death is a function of ouregos, which burden us with a senseof separateness that can becomeunbearable when we approach death.‘We are born into an egoless world,’Cohen wrote, ‘but we live and dieimprisoned within ourselves. Wewanted to provide a brief, lucid interval of complete egolessness to demonstrate that personal intactness wasnot absolutely necessary, and thatperhaps there was something ‘outthere’ something greater than our individual selves that might survive ourdemise.’” Cohen shares the words ofone patient, dying of ovarian cancer,7

who states, “My extinction is not ofgreat consequence at this moment,not even for me. It’s just another turnin the swing of existence and nonexistence. I could die nicely now –if it should be so. I do not invite it, nordo I put it off” (339). Similarly, presentday NYU psychiatrist Jeffrey Guss“speaks explicitly about the acquisition of meaning, telling his patients,‘that the medicine will show youhidden or unknown shadow parts ofyourself; that you will gain insight intoyourself and come to learn about themeaning of life and existence. Asa result of this molecule being in yourbody, you’ll understand more aboutyourself and life and the universe’”(354). Pollan concludes, “And moreoften than not this happens. Replacethe science-y word ‘molecule’ with‘sacred mushroom’ or ‘plant teacher,’and you have the incantations of ashaman at the state of a ceremonialhealing” (354). Jeffrey Guss is optimistic that psychedelics might offera paradigm shift for psychotherapy.He points out that “for many yearsnow ‘we’ve had this conflict betweenthe biologically based treatments andpsychodynamic treatments. They’vebeen fighting one another for legitimacy and resources. Is mental illnessa disorder of chemistry, or is it a lossof meaning in one’s life? Psychedelictherapy is the wedding of those twoapproaches” (335).But how to understand what ishappening to the brain, overthe course of a psychedelicsession? Michael Pollan looks to ateam at the Centre of Psychiatry onthe Hammersmith campus of ImperialCollege in West London for a promising and still preliminary understanding. This team, led by neuroscientistRobin Carhart-Harris, uses scanningtechnologies such as functionalmagnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)to observe people injected with ahigh dose of psilocybin or LSD. Bothmolecules have an affinity with “oneparticular type of serotonin receptorcalled the 5-HT2A. These receptorsare found in large numbers in the8human cortex, the outermost andevolutionarily most recent layer ofthe brain” (292). This appreciation ofreceptor sites doesn’t explain muchabout the “phenomenology” of abrain subjected to psychedelics. Tothat end, Carhart-Harris’s team is interested in what is called the “defaultmode network,” (DMN) a “networkof brain structures that light up withactivity when there are no demandson our attention and we have no mental task to perform. Working at aremove from our sensory processingof the outside world, the default modeis most active when we are engagedin higher-level ‘metacognitive’ processes such as self-reflection, mentaltime travel moral reasoning, and‘theory of mind’ - the ability to attribute mental states to others, as whenwe try to imagine ‘what it is like’ to besomeone else” (302). The adult brain,according to Carhart-Harris, is “ahierarchical system,” in which “‘Thehighest-level parts’ - those developedlate in our evolution, typically locatedin the cortex - ‘exert an inhibitory influence on the lower-level [and older]parts, like emotion and memory”(303). In Carhart-Harris’s first experiment, “the steepest drops in defaultmode network activity correlated withhis volunteers’ subjective experienceof ‘ego dissolution.’ (‘I existed onlyas an idea or concept,’ one volunteerreported. Another recalled, ‘I didn’tknow where I ended and my surroundings began.’) The more precipitous the drop-off in blood flow andoxygen consumption in the defaultnetwork, the more likely a volunteerwas to report the loss of a sense ofself” (305). While the default modenetworks go quiet, the limbic regionsinvolved in emotion and memory,are disinhibited, which might explainwhy “material that is unavailable tous during normal waking consciousness now floats to the surface ofour awareness, including emotionsand memories and, sometimes,long-buried childhood traumas”(307). The DMN also “helps regulate what is let into co

Archivist—ralph Cox Reviews Editor—mical moser Webmaster—ethan Crenson www.newyorkmyc.org . knife, a whistle (in case you get lost or injured), and a basket for mushrooms. Please let a walk leader . Greg Thorn grew up in