Transcription

A P U B L I C AT I O N O F E M O RY E Y E C E N T E R 2011-2012eyeSmaller is better 15The eyes have it 17011-2012 Emory EyeLighting up 2ourworld 191

From the director Looking forward and outward“I like the dreams of the future better than the history of the past.” Thomas JeffersonOur program has a unique history and we owe much to those who brought us to wherewe are today. We are at the end of the beginning stage in building the Emory Eye Center of thefuture. We have like-minded, passionate and collaborative faculty who work hard to offer thefinest in patient care, teaching and education. Next, we continue to recruit the brightest and mosttalented collaborative physicians and researchers in the country. We aretransforming the Eye Center.How does the transformation of the Eye Center continue? We work asa team, and capitalize on many of the opportunities around us at Emory, inAtlanta, and beyond. We select unique opportunities that will allow us todistinguish our program and offer new ways to “help people see as well asthey can see,” our overriding mission. In this issue, you’ll begin to see howwe are expanding further outward with the Emory Global Vision Initiative(EGVI).The Emory team is going global . . . “Global-Eyes”! We’ve recruitedtwo leaders in international ophthalmology, visiting scholars Susan Lewallen, MD and Paul Courtright, DrPH. Both bring a wealth of experience incommunity ophthalmology and are now busy framing the architecture fora sustainable and meaningful international program.Are we going global at the risk of compromising our local efforts? Absolutely not. In fact, we will enhance our local outreach. Two key issues thatare important both globally and locally are: health care disparity and access to care. In fact, ourprogram at Grady has worked nearly 130 years (since 1892) to provide care and access to care forthe needy of Atlanta and Georgia. Yes, global vision includes the Atlanta community and Georgia. We anticipate that our program has the potential to be a national leader in addressing disparity and access to care issues here at home.I look forward to the evolution of our Global Vision Initiative and engaging our team at theEmory Eye Center into the larger Emory University and the Atlanta community . . . continuingthe evolution of the Eye Center!Timothy W. Olsen

eye2621“Instead of taking exactly what wedo here and trying to plop it intowe have tofigure out how it can workthere, and how muchit will cost”.—Hreem Dave, MDanother country,613EMORY EYE MagazineDIRECTOR:Timothy W. Olsen, mdEDITORS: JoyBell, David WoolfCONTRIBUTORS:DESIGN:WEB SITE:E-MAIL:2Feature Cosmetic procedures12 Oculoplastics physicians not only enhance appearancebut can help open up vision.15News Smaller is better A newly patented microneedle provides targeteddrug delivery.News The eyes have it17 An innovative, new way to photograph the backof the eye in the emergency room.News Lighting up our world19Giving Back Friends of the Emory Eye Center20 Joy Bell, Ginger PyronPeta WestmaasPHOTOGRAPHY:Feature “Expanding our sphere of vision” The eye? Think bigger: The globe.Donna Price (lead), David Woolfwww.eyecenter.emory.edueyecenter@emory.eduTHE EMORY EYE CENTER IS PART OF EMORY UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OFMEDICINE AND EMORY HEALTHCARE, BOTH OF WHICH ARE COMPONENTSOF EMORY’S WOODRUFF HEALTH SCIENCES CENTER.Faculty News Of note, awards & rankings Our faculty’s noteworthy accomplishments.Faculty New faculty members2224Emory Eye Center Uncommon knowledge. Uncommon sharing.

Feature Going global2 Emory Eye 2011-2012

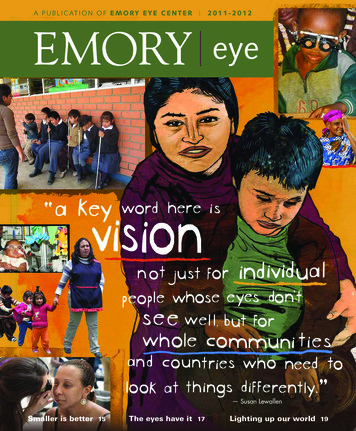

Expanding our sphere of visionThe eye? Think bigger: The globe.ByGinger Pyron Cover illustration byKaren BlessenQuick: When you read thephrase “Global Vision Initiative,”what do you picture?If you imagined a few intrepid physicians setting up U.S.-sponsored eye clinics in underdeveloped countries “somewhere over there,” you’re not alone.That visual cliche, however, is fast disappearing, thanks to community health strategistsSusan Lewallen, and Paul Courtright, who were recruited by Timothy Olsen to align newopportunities for research and education for the facultyand trainees at the Emory Eye Center. They are helpingget the program off to a rolling start.The Global Vision Initiative, its mission aligned withthat of Emory’s Global Health Institute, involves farmore than clinical eye care. Stretching across the vastfield of ophthalmology-related service, research, andteaching, it seeks to generate operative and sustainable systems that can be implementedworldwide—not only in countries near and far, developed and developing, but right herein the underserved communities of Atlanta. From the perspective of this global healthprogram, “the world” starts close to home.2011-2012 Emory Eye 3

Feature Going globalGlobal vision involves local outreach where it’s needed as well as serving those in distant countries.Seeing eye to eye In 2009 a seminalconversation took place over breakfastat the Emory Conference Center. TimOlsen, Paul Courtright, and DannyHaddad, director of the InternationalTrachoma Initiative (brought togetherthrough a connection with a formerEmory Eye Center resident, HunterCherwek) talked over a multitude ofpossibilities and agreed on the first steptoward a future Emory Global VisionInstitute.Having co-directed with Lewallenthe Kilimanjaro Centre for CommunityOphthalmology (KCCO) in Moshi, Tanzania, over the past decade, Courtrightsaw the abundant advantages of partnering with other institutions and organizations in Atlanta, such as the RollinsSchool of Public Health, the Centers forDisease Control, the International Trachoma Initiative, and the Carter Center.Inspiration, opportunity, and timing worked in the Eye Center’s favor.Courtright and Lewallen, who in 2008together received the American Academy of Ophthalmology InternationalBlindness Prevention Award, joined theEmory faculty as visiting scholars inFebruary 2011, committed to the initialstrategizing on behalf of the Global Vision Initiative.Seeing differently Internationaloutreach is not new to the Emory EyeCenter.4 Emory Eye 2011-2012Over the past 20 years, for example,the Anderson Fellows endowment hasbrought a total of nine fellows fromYonsei University in Seoul, South Korea,to learn translational research from ourfaculty. Recently, working closely withDr. Luz Gordillo in Peru, we participated in a study on the cost effectivenessof laser treatment for retinopathy ofprematurity, in comparison to no intervention. Nancy Newman and ValérieBiousse, professors of ophthalmologyand neurology, extend the educationalarm of our global health program notonly by training many neuro-ophthalmologists from around the world but byserving as guest lecturers and creatingcourses worldwide. Some of our facultyand residents have traveled independently to other countries to providetreatments and surgeries for underserved people.But all of us still have a lot to learnabout addressing the world’s vision challenges. Once Lewallen arrived, she lostno time in opening our eyes.On February 4, speaking to Emoryphysicians, she said, “In the developingcountries, the major problem is not—aspeople often think—just that there aretoo few ophthalmologists. Rather, it’sthat the available ones may lack the support, equipment, and supplies to workproductively. You can have a legion oftrained ophthalmologists, but withoutadequate management systems, blind-ness will remain a problem.”Lewallen wants Emory’s ophthalmologists to understand that while theefforts of individual doctors are usefuland important, those efforts alone won’teffect big changes. What matters evenmore, she says, is to establish ongoingprograms that provide much-neededservices such as training or diabeticscreening.Toward that purpose, she adds, public health professionals can be a tremendous resource of knowledge and perspective: “Once you learn to address aproblem from a public health or systemsapproach, you start to see things in anew way and thus can make more effective choices. For example, if doctors gointo a country without first finding outwho else is there, unwittingly they mayset up a free clinic just 10 miles awayfrom where a local ophthalmologist ispracticing, trying to make a living.”Lewallen advises mission-mindedphysicians, “A more helpful strategywould include doing thorough homework before the trip, and then seekingways to work within the area’s existingsystems.”Thinking big “Improving global vi-sion”: That’s a grand, even potentiallygrandiose, idea—one that, to becomeeffective, requires its proponents tostep way back and get a panoramicview. Two - C O N T I N U E D O N P A G E8

Taking the initiative . downtownSusan Primo—director of vision and optical services andassociate professor of ophthalmology—has the distinction of being the only faculty member of the Emory EyeCenter with a graduate degree in public health. From herdual perspective, she thinks the GlobalVision Initiative is likely to take thedepartment of ophthalmology in a veryproductive direction.“As eye care specialists, we tend tofocus on taking care of the eye, not always aware that the eye is just one partof the body system,” she says. “We alsoneed to understand that good visualhealth influences good overall health.”She believes that if we want to address big problems of vision, whetherhere at home or throughout the world,a collaborative effort is essential: “Weneed everybody at the table—from policy folks to healtheducation folks to epidemiologists.”Primo commends the approach that visiting scholarsSusan Lewallen and Paul Courtright are taking toward theGlobal Vision Initiative—“They’re doing an incredible job ofjump-starting this much-needed program for us.”—and sheparticularly applauds the efforts of Tim Olsen: “He doesn’thave a public health background, but he is broadening histhinking and is ready to push this initiative to the next level.I think the Global Vision Initiative will help meet some of thebig challenges.”A couple of decades back, getting her first taste of publichealth work while training in a community health center,Primo began to develop the passion that she still feels for themedically vulnerable population: the children, the elderly, theworking poor, the uninsured and underinsured, and particularly those with unmet needs for eye care and vision care.Later, working toward her master’s degree in publichealth, she began to see that undetected or untreated eyeproblems involve much more than the eye. “This is definitelya public health issue,” she says, “because it includes questions of access, behavior, understanding, beliefs, cultures—the whole gamut. That’s why it requires a comprehensivestrategy.”“My heart is in clinical work,” Primo acknowledges. Herclinical responsibilities—along with her own initiative—takeher downtown, both to Grady Memorial Hospital, where sheinteracts primarily with medical residents, and to KirkwoodFamily Medicine, a neighborhood health center under theauspices of the Grady Health System.“I spend the bulk of my time at Grady sites,” she says,“because this is the type of work I enjoy most: trying toreduce the incidence or prevalence of visual impairment andvisual problems.”Primo explains that at the neighborhood center, the firsttask is to attempt a diagnosis, then to create access and “getpeople into the system”: “Once that’s done, we can help laterwhen they develop problems related to vision loss, whetherit’s something simple, such as glasses, or a potentially blinding eye disease such as cataracts and glaucoma.”Anticipating the next phase of the Global Vision Initiative,Primo says she is eager to help: “What I hope to bring to thetable is my public health background. Perhaps I can helpsecure some grants and funding to sustain the program aswell as funnel it in directions that are most useful—not onlyfor Georgia, but also for the world.”To Dharamsala—Again!Along with other Emory University scientists, the EmoryEye Center’s Michael Iuvone, Ferst Professor of Ophthalmology and director of research, returns this summerto Dharamsala, India, in thefoothills of the Himalayas.During his 10-day visit,Iuvone will continue his participation in the Robert A.Paul Emory-Tibet Science Initiative (ETSI): teaching neuroscience, via lectures and other structured activities, to a selectgroup of Tibetan monks, who then can return to their ownmonasteries to share their new knowledge.The project, now in its fourth year, has a mandate (partially from the Dalai Lama) to train Tibetan monks in thesciences. Last summer, six of the monks in the group wereselected to further their studies at the Emory campus for the2010-11 academic year.2011-2012 Emory Eye 5

Feature Going globalPublic Health Economics in PeruIn Peru, retinopathy of prematurity(ROP)—a disease of the retina, whichcauses blindness in premature infants—has been on the rise.Through a collaborative researchproject, an Emory team investigated thesocietal burden of blindness in relationto ROP. Support for the project camefrom the Emory Global Vision Initiative, the Emory School of Medicine, theRollins School of Public Health, andan unrestricted grant from Research toPrevent Blindness.Results of the study led theteam to conclude that increasing theearly screening and treatment of ROPnot only prevents unnecessary blindness but is significantly cost-effectivefor society.For an educated adult in Peru, themean annual income is 8,000. Thusthe cost of ROP treatment for a singlechild is equivalent to employing 24 educated adults full-time for an entire year.The lifetime cost savings for societyfor the next generation is estimated at 516 million.Timothy W. Olsen, Eye Center director, led the 2011 study. Through HunterCherwek, who trained at the Emory EyeCenter, and ORBIS International, a nonprofit organizationfighting blindness indeveloping countries, he becameacquainted with thework of Luz Gordillo,a U.S.-trained pediatric ophthalmologistin Lima. An EmorySchool of Medicinethird-year student,Hreem B. Dave,helped develop andexecute the project, and Monica S.Zhang joined thegroup as translator.“We were fortunate to have manyresources,” Dave says. “Dr. ZhouYang, from the Rollins School of PublicHealth, brought a very valuable per-Facts from the team’s cost-analysis (in USD):Estimated total indirect cost to the country, for eachPeruvian child with neonatal blindness related to ROP: 197,753Total direct cost to Peru, for ROP-related laser treatmentof just one child: 2,496Amount that Peru can save, over the lifetime of each affected child,by using the laser treatment: 195,2576 Emory Eye 2011-2012spective. Her PhD is in health economics, and she helped us figure out howto approach the study in a way that’slogical from a health economics pointof view.”The study and its data, Dave explains, can provide useful guidance fordecision makers in Peru: “This economic data, combined with our medical knowledge about the natural historyof ROP, will be important to presentto health care ministers in Lima. It willhelp them make appropriate decisionson how to allocate their resources inthe future.”During a weeklong trip to Lima, thegroup accumulated data, observedthe day-to-day clinical work of Gordillo, investigated the support systemsavailable for a blind person in Peru, anddetermined the resources needed.“Here, we know what we wouldneed to treat someone who has ROP,and those resources are available,”Dave observes. “But what if you’reworking in a rural area without electricity? Instead of taking exactly whatwe do here and trying to plop it intoanother country, we have to figure outhow it can work there, and how much itwill cost.”Public health, she explains, analyzeslocal situations and puts them in acultural context, “so that our work canhave the impact that we’re intending.We have to make contact with doctors there who know how to work thesystem and have been able to deal withminimal resources.”Dave says with admiration, “Dr.Gordillo’s role in this project cannot beoverestimated. She has been the MDequivalent of a Florence Nightingale,addressing this public health issue inher home country of Peru and do-

ing work that sets the stage for othermiddle-income countries around theglobe.”On May 3, 2011, at the annual meeting of the Association for Research inVision and Ophthalmology (ARVO), theteam presented its study, “The SocietalBurden of Blindness Secondary to Retinopathy of Prematurity in Lima, Peru.”The Emory team is hoping to see thestudy published in a medical journal, sothat Gordillo can use it as a resourcewhen she meets with Peruvian ministers of health.After her May graduation fromEmory, Dave begins her residency atRush University in Chicago. As Davemoves on, another third-year medicalstudent, Christopher Williams, will betaking over the project. He plans toinvestigate the importance of systemictherapy and neonatal oxygen therapyto lower the burden of ROP in middleincome countries.“I’d like to keep doing internationalprojects, helping make health careavailable to everyone,” Dave says. “ButI also know it’s important to do thatwork here.” She has been a frequentvolunteer with Student Sight Savers,doing glaucoma screenings at Atlantahealth fairs and churches.Like many who have seen enormous health care needs firsthand, Davefocuses on positive results. “One ofthe biggest things we realized in doingthe ROP study,” she concludes, “is thatsomething small can make a huge difference. If laser treatment can save thevision of only four out of ten childrenin Peru who are at risk for ROP, thatmeans four children can grow up tobe adults and will have a much betterquality of life.”Research by the community,for the community“Right now, we’re still just planting the seeds,” says international ophthalmologist Susan Lewallen.Along with confirmed or potential partners—the Lions Lighthouse, Prevent Blindness Georgia, some student groups, and some community groupsaround the city—she’s envisioning a network that can start changing thefuture of Atlanta’s vision-related public health right away.In this endeavor, the first and most important word is together. Oncepeople from these interested groups meet around the same table, they canbegin investigating the vision issues in Atlanta that they themselves, fromfirsthand experience, consider top priority. Formed to conduct what’s called“community-based, participatory research,” the network frames questionsthat will determine their next steps: What do we already know about visioncare needs here? What other questions should we be asking? How do wecapture the full story of vision-related problems, from diagnosis and accessto treatment and follow-up?“The community groups help determine the priorities and pose thequestions,” Lewallen emphasizes. “For example, maybe they will decide totalk with community people who’ve gone blind from glaucoma or diabeticretinopathy and to document their journey of care. What barriers did thosepeople encounter when seeking out medical help? What situations—perhapsbeyond the patients’ control—added to their struggle?”From grass-roots concerns and through grass-roots inquiry, the largernetwork of community partners can learn what needs doing first. Then thecoordinators of the project can draw on the network’s resources of funds,people, and ideas to set up health education activities and screenings thathelp address problems of access to vision care.At this point, the details are still taking shape. “The project doesn’t evenhave a name yet,” Lewallen says. She’s aware of enthusiasm for the ideaamong several people at the Emory Eye Center, including Annette Giangiacomo, assistant professor of glaucoma, and Susan Primo, associate professor of ophthalmology.“These two doctors share a keen interest in glaucoma, which is one of themajor causes of blindness in Atlanta’s underserved population,” she says.“And Primo has a master’s degree in public health, plus a lot of experience inthe communities.”In keeping with Lewallen’s tried-and-true principles for all new publichealth programs, the prospective “community-based, participatory researchnetwork” will start small, plan carefully, seek funding, take on a project or twoas a group, and then see how its efforts can grow.With her usual optimism, Lewallen shares her own vision: “I’m looking atthis project as the kernel that might eventually become the thriving Atlantabranch of the Global Vision Initiative.”2011-2012 Emory Eye 7

Feature Going globalCommunity ophthalmology in Tanzania often involves transportation help and outdoor diagnostis.big, related topics that inform Olsen’sthinking about the initiative’s future aredisparity and access.“We know a great deal about howto treat eye diseases,” he observes, “butin health care worldwide, disparity—awidening gap in either informationor financial resources—is a seriousproblem. I hope that the Global VisionInitiative can help reduce the knowledgegaps through education.”Courtright explains that the problemof health care access is complex—andgrowing: “To achieve some level ofequity, we don’t have to sacrifice thequality of care. But we do have to ensurethat people in need of services are in aposition to access them. This issue is being faced everywhere in the world, andit’s going to be faced here in America.”Partnerships with other aspects ofmedicine, with public health, and withcommunity groups such as the LionsLighthouse and Prevent Blindness Georgia he says, are essential to eye care’ssurvival and growth.Thinking big—and bigger—aboutglobal vision can also involve remembering that major challenges exist hereas well as there. “When I talk withfriends of the Eye Center about globalvision projects that we could pursuein Africa, South America, and LatinAmerica,” Olsen says, “someone alwaysbrings up local conditions: What aboutthe health care disparity right here in8 Emory Eye 2011-2012Atlanta? or You know, Grady Hospital isalso on the globe.”To Lewallen, that point is crucial.“I came here thinking that the biggestneed was overseas, but now, havingvisited Grady Memorial Hospital andhaving talked with both Prevent Blindness Georgia and the Georgia LionsLighthouse—the two main communitygroups trying to provide eye care forpatients who don’t have insurance—Isee that conditions here in Atlanta arejust as urgent. And they may be moreimportant to people here than overseasissues are. I imagine that Emory’s GlobalVision Initiative is going to be just asactive in Atlanta and Georgia as in othercountries.”In Atlanta as in Moshi, Tanzania, theproblem of access includes a range oflimitations: Many people lack the meansto pay. People needing eye care my notknow where to go for help, or may havedifficulty getting there. Someone whohas a job may be unable to take time offfor a medical appointment.“Follow-up care after a diagnosisposes another big challenge,” Lewallenadds, “and in some ways it’s an evenbigger problem here than in Africa.Locally there’s a huge population that’snot served. For example, if doctors at afree community clinic find that a patientwithout insurance needs surgery, theymay have to scramble to find a placewhere that person can be operated on.In Africa, our work with the KCCOhas resolved that complication; we runour outreach clinics from a base hospital, where we can perform surgery asneeded.”Since most U.S. ophthalmologistswork in medical clinics—where patientscome to them— they may not encounterproblems of disparity and access, maynot think about all the systems thatmust be in place before an ophthalmologist can see patients and save vision.“But as physicians,” Lewallen states,“we have a responsibility to think aboutthose things. We need to help make eyecare possible for people.”One physician who takes that responsibility seriously is the Eye Center’sGeoff Broocker, Walthour-DeLaPerriereProfessor of Ophthalmology and chiefof service at Grady Memorial Hospital.For the past 23 years he not only hastrained hundreds of Emory medicalresidents but has treated countless patients who need treatment they cannotpay for.He’s also a tireless advocate for thisincreasingly at-risk population. “Forthe first time in my professional career,” Broocker says, “I’m taking care ofpatients who cannot get their medications or their surgery. Social workers aretelling me that outside funds are dryingup, going nonexistent. At Grady, too,resources are limited. How are thesepeople going to get access to care? And

these problems are just the tip of the iceberg for what I think we can extrapolateto health care across the U.S. in the next10 to 5 years.”According to Lewallen, there’s stillsome good news: “Like Dr. Broocker, alot of concerned ophthalmologists arelooking at the local issues and are reallyconcerned about them. I admire thosepeople; they have opened my eyes.”Courtright adds, “Global means thewhole picture, and there’s learning to bedone on all sides of it. What people fromthe Emory Eye Center and its partnerscan figure out within the setting ofAtlanta will help provide solutions toissues in other countries. And vice versa:When we learn how people deliverservices in settings beyond the U.S., weneed to consider what those methodscan offer us here.”Eye Center director Timothy Olsen (left) with Woon Cho Kim, Paul Anderson Sr.,and former Eye Center research director Henry Edelhauser.Starting small Six months of lay-ing groundwork, of course, isn’t goingto result immediately in a 10-milliongrant from the National Institutes ofHealth, or a plan for solving the cataractproblem for the continent of Africa, oran internationally renowned Global Vision Institute. All three members of thecore strategic team—Olsen, Lewallen,and Courtright—agree on that.They also agree on the two mostuseful ways to spend these months:taking some thoughtful small steps anddeveloping the vision. “We have to startsmall,” Olsen says. “Before we can lookfor any major funding, we need to provethat we have the people and the expertise to carry this program through.”Plans for this phase of the initiative include some of the methods thatLewallen and Courtright routinely employ for setting up community ophthalmology programs in eastern Africa:1) Identify the stakeholders—asmany as possible.For the Global Vision Initiative, thisTranslational—and transnationalTranslational research: integrating the latest thinking and results invision research with clinical education and treatments. At the EmoryEye Center, that’s a point of emphasis. And for two decades, thanks to theAnderson Fellowship program, we’ve had the privilege of sharing it withclinicians and scientists from Korea.Paul Anderson Sr. (’38C-’40L) established the fellowship in 1987 tohonor his father, Earl Wills Anderson (1901C), a medical missionary whowas instrumental in helping to found one of Korea’s first ophthalmology departments, at Severance Hospital and the medical school now affiliated withYonsei University in Seoul. The endowment supports approximately a yearof study for one Yonsei fellow at the Eye Center every two years.The longstanding alliance between the Emory Eye Center and YonseiUniversity has provided for the valuable exchange of skills between countries. The first Anderson Fellow, Eung Kwan Kim (affectionately known as“E.K.”), is now a world-renowned professor who specializes in cornea andrefractive surgery at Yonsei University. His fellowship at Emory was underthe direction of Henry F. Edelhauser, the Eye Center’s director of research atthe time.And the connections continue. Kim’s daughter, Woon Cho Kim, is acurrently enrolled medical student at the Emory School of Medicine. Notsurprisingly, a career in international medicine is among her aspirations.2011-2012 Emory Eye 9

Feature Going globalGlobal views on pediatric cataractsIn March, the EmoryEye Center hosted anInternational CongenitalCataract Symposium inNew York City, wherepediatric ophthalmologists and epidemiologists from Egypt, Tanzania, Bangladesh, Indiaand England discussedNihal El Shakankiri, a pediatric ophthalmologistthe global need to profrom Alexandria, Egypt; Emory Eye Center’s ScottLambert; and Emory researcher Carey Drewsvide surgery for childrenBotsch of the Rollins School of Public Health.who have a cataract,now the leading causeof childhood blindness in many developing countries.The meeting—supported by funding from industry sponsors, the Georgia Knights Templar Educational Foundation Inc., the March of Dimes, andthe von Habsburg Foundation—brought together knowledge and data fromaround the world, perhaps lessening current disparities in health care.Directing the event were Emory Eye Center’s Scott R. Lambert, R. HowardDobbs Professor of Ophthalmology and Pediatrics; Edward Cotlier, a researchscientist at New York State Institute for Basic Research in Developmental Disabilities; and David Taylor, professor emeritus, University of London.Lambert is the national study chair for the National Institute of Health’s Infant Aphakia Treatment Study (IATS), covered in our last issue of Emory Eye—amulti-year, multi-clinic study to determine whether an intraocular lens (IOL) or acontact lens is the best treatment for optimal vision in young children, following removal of the cataract.list comprises all the potential partnerinstitutions and organizations that thevisiting scholars already have beguncontacting.2) Work toward the commonvision.In face-to-face meetings with eachstakeholder group, ask questions likethese: “What’s the situation right now?What do people here want?” Try tounderstand their vision; find out whatsynergies they see between what they donow and what the Eye Center potentially can do alongside them.10 Emory Eye 2011-20123) Establish strong links betweenthe Eye Center and the Rollins Schoolof Public Health.The RSPH has been an obvious placeto start. Overlapping areas of interest exist between the Global Vision Initiativeand all six of the school’s departments,making these two entities natural partners. “We’

EMORY EYE CENTER 2011-2012. Smaller is better . 15. The eyes have it . 17. Lighting up our world . 19 "I like the dreams of the future better than the history of the past." Thomas Jefferson . Our program has a unique history and we owe much to those who brought us to where .