Transcription

United States Department of AgricultureA Technical Guide for Monitoring Wildlife HabitatA Technical Guide forMonitoring Wildlife HabitatForestServiceGen. Tech.Report WO-89October 2013

Metric EquivalentsWhen you know:Multiply by:Inches (in)Feet (ft)Miles (mi)Acres (ac)Square feet (ft2)Yards (yd)Square miles (mi2)Pounds (lb)2.540.3051.6090.4050.09290.9142.590.454To find:CentimetersMetersKilometersHectaresSquare metersMetersSquare kilometersKilograms

United StatesDepartmentof AgricultureForest ServiceA Technical Guide forMonitoring Wildlife HabitatGen. Tech.Report WO-89October 2013Technical EditorsMary M. RowlandChristina D. VojtaAuthorsC. Kenneth BrewerSamuel A. CushmanThomas E. DeMeoMichael I. GoldsteinGregory D. HaywardRebecca S.H. KennedyGreg KujawaMary M. ManningPaul A. MausClinton McCarthyLyman L. McDonaldKevin McGarigalKevin S. McKelveyTimothy J. MersmannGretchen G. MoisenClaudia M. ReganBryce RickelMary M. RowlandBethany SchulzLinda A. SpencerLowell H. SuringChristina D. VojtaJames A. WestfallMichael J. Wisdom

Rowland, M.M.; Vojta, C.D.; tech. eds. 2013. A technical guide for monitoring wildlife habitat. Gen. Tech. Rep. WO-89.Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: 400 p.The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race,color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion,sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derivedfrom any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who requirealternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’sTARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Officeof Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202)720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.The use of trade, firm, or corporation names in this document is for the information and convenience of the reader and doesnot constitute an endorsement by the Department of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable.Cover photo: The cover images illustrate the primary sources of habitat monitoring data: field data (front cover), remotesensing data (back cover), and existing data sources (the hexagonal grid of the Forest Inventory and Analysis [FIA] program superimposed on a topographical map; back cover). The three wildlife species are those featured in the guide as caseexamples of habitat monitoring: American marten (Martes americana), greater sage-grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus),and marbled salamander (Ambystoma opacum), representing the group of mole salamanders. Photo credits: bat habitatmonitoring in bottomland hardwood forest, Susan Loeb; American marten, Erwin and Peggy Bauer; greater sage-grouse,Stephen Ting; marbled salamander, Lloyd Gamble; FIA image, Randall S. Morin; person with increment borer, MichelleGerdes; dot grid overlay, Remote Sensing Applications Center; and image of kernel estimator for the probability of salamander dispersal, Kevin McGarigal.

AcknowledgmentsThe technical editors and authors thank the following U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service employees for providing technical expertise and consultationon one or more chapters: Jim Alegria, Seona Brown, Renate Bush, Chris Carlson,Chris Colt, John Coulston, Diana Craig, Nick Crookston, Don Haskins, Phil Hyatt,Rose Lehman, Paul Maus, Clint McCarthy, Rob Mickelsen, Martha Mousel, MarkNelson, Mark Orme, Hugh Safford, Charles (Chip) Scott, Sue Stewart, Dave Tart,Jack Triepke, and Ed Uebler. Additionally, we thank Oz Garton and Jim Peek (University of Idaho, retired), Ryan Nielson (WEST, Inc.), and Steve Sesnie (U.S. Fish andWildlife Service) for their technical contributions.We are grateful to the following people within the Forest Service who contributedfigures and graphics: Doug Berglund, Sam Cushman, Lloyd Gamble, Jennifer Hafer,Greg Hayward, Mark Penninger, and Frank Thompson. Anne McIntosh (University ofAlberta), Darrell Pruett (Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife), and PatriciaHayward (University of Idaho) also contributed graphics. Forest Service employeesGiana Gallo, Katherine (Casey) Giffen, and Lynn Sullivan provided editorial assistance;Dan White (Big H Design, Inc.) prepared graphics; and Shelly Witt (Forest Service)created and maintained a file-sharing Web site for authors. We thank the followingForest Service personnel for providing internal reviews: Ken Brewer, Ray Czaplewski,Tom DeMeo, Mike Goldstein, Beth Hahn, Sarah Hall, Phil Hyatt, Rebecca Kennedy,Rudy King, Kevin McKelvey, Tim Mersmann, Gretchen Moisen, Wayne Owen, DougPerkinson, Doug Powell, Martin Raphael, Bryce Rickel, Barb Schrader, Dave Tart,and Jim Westfall. Statistician Lyman McDonald (West, Inc.) also reviewed chapters.We greatly appreciate the external peer review organized by Gary Meffe of the Societyfor Conservation Biology and conducted by 15 anonymous reviewers.We also value the institutional support of Chris Iverson and Anne Zimmermannof the Forest Service Watershed, Fish, Wildlife, Air, and Rare Plants Staff and TonyTooke, Patrice Janiga, and Rick Ullrich of the Ecosystem Management CoordinationStaff. We acknowledge Richard (Holt) Holthausen, National Wildlife Ecologist forthe Forest Service, for his leadership during the inception and early stages of thetechnical guide and for motivating us long after his retirement.A Technical Guide for Monitoring Wildlife Habitatiii

Technical EditorsMary M. Rowland, Research Wildlife Biologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture(USDA), Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Forestry and RangeSciences Laboratory, La Grande, OR 97850 USA.Christina D. Vojta, Wildlife Ecologist (retired), USDA Forest Service, WashingtonOffice, Terrestrial Wildlife Ecology Unit, Stationed at Rocky Mountain ResearchStation, Flagstaff, AZ 86001 USA. Currently, Associate Director, Landscape Conservation Initiative, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ 86001 USA.AuthorsC. Kenneth Brewer, Remote Sensing Research Program Leader (retired), USDAForest Service, Washington Office, Quantitative Sciences, Arlington, VA 22209USA.Samuel A. Cushman, Research Wildlife Biologist, USDA Forest Service, RockyMountain Research Station, Wildlife Ecology Research Unit, Flagstaff, AZ 86001USA.Thomas E. DeMeo, Vegetation Ecologist, USDA Forest Service, Pacific NorthwestRegion, Portland, OR 97204 USA.Michael I. Goldstein, Wildlife Ecologist, USDA Forest Service, Alaska Region,Juneau, AK 99801 USA. Currently Special Projects Coordinator for Climate Change,Alaska Region.Gregory D. Hayward, Wildlife Ecologist, USDA Forest Service, Alaska Region,Chugach and Tongass National Forests, Anchorage, AK 99501 USA.Rebecca S.H. Kennedy, Research Ecologist (former), USDA Forest Service, PacificNorthwest Research Station, Corvallis, OR 97331 USA.Greg Kujawa, Silviculturist, USDA Forest Service, Washington Office, ForestManagement, Washington, DC 20250 USA. Currently, Senior Staff Assistant, USDAForest Service, Washington Office, Climate Change Advisors’ Office, Washington,DC 20250 USA.Mary M. Manning, Vegetation Ecologist, USDA Forest Service, Northern Region,Ecosystem Assessment and Planning, Missoula, MT 59807 USA.Paul A. Maus, Remote Sensing Specialist, USDA Forest Service, Washington Office, Remote Sensing Applications Center, Salt Lake City, UT 84119 USA.ivA Technical Guide for Monitoring Wildlife Habitat

Clinton McCarthy, Regional Wildlife Ecologist (retired), USDA Forest Service,Intermountain Region, Ogden, UT 84401 USA.Lyman L. McDonald, Senior Biometrician, Western Ecosystems Technology, Inc.,Cheyenne, WY 82001 USA.Kevin McGarigal, Associate Professor, University of Massachusetts, Department ofNatural Resources Conservation, Amherst, MA 01003 USA.Kevin S. McKelvey, Research Ecologist, USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Re search Station, Wildlife and Terrestrial Ecosystems Program, Missoula, MT 59801 USA.Timothy J. Mersmann, Wildlife Biologist, USDA Forest Service, State and PrivateForestry, Atlanta, GA 30367 USA. Currently, District Ranger, Conecuh NationalForest, Andalusia, AL 36420 USA.Gretchen G. Moisen, Research Forester, USDA Forest Service, Forest Inventoryand Analysis, Ogden, UT 84401 USA.Claudia M. Regan, Vegetation Ecologist, USDA Forest Service, Rocky MountainRegion, Lakewood, CO 80225 USA.Bryce Rickel (deceased), Wildlife Biologist, USDA Forest Service, SouthwesternRegion; Watershed, Fish, Wildlife, Air, and Rare Plants; Albuquerque, NM 87102USA.Mary M. Rowland, Research Wildlife Biologist, USDA Forest Service, PacificNorthwest Research Station, Forestry and Range Sciences Laboratory, La Grande,OR 97850 USA.Bethany Schulz, Research Ecologist, USDA Forest Service, Pacific NorthwestResearch Station, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, Anchorage, AK 99513 USA.Linda A. Spencer, Vegetation Ecologist, USDA, Forest Service, Washington Office,Ecosystem Management Coordination, Stationed at Custer National Forest, Billings,MT 59105 USA. Currently, Washington Office, Natural Resource Manager, stationedat Alaska Region, Juneau, AK 99801 USA.Lowell H. Suring, Wildlife Ecologist (retired), USDA Forest Service, WashingtonOffice, Terrestrial Wildlife Ecology Unit, Stationed at Rocky Mountain ResearchStation, Boise, ID 83702 USA. Currently, Principal Wildlife Ecologist, NorthernEcologic L.L.C., 10685 County Road A, Suring, WI 54174 USA.A Technical Guide for Monitoring Wildlife Habitatv

Christina D. Vojta, Wildlife Ecologist (retired), USDA Forest Service, WashingtonOffice, Terrestrial Wildlife Ecology Unit, Stationed at Rocky Mountain ResearchStation, Flagstaff, AZ 86001 USA. Currently, Associate Director, Landscape Conservation Initiative, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ 86001 USA.James A. Westfall, Research Forester, USDA Forest Service, Northern ResearchStation, Forest Inventory and Analysis, Newtown Square, PA 19073 USA.Michael J. Wisdom, Research Wildlife Biologist, USDA Forest Service, PacificNorthwest Research Station, Forestry and Range Sciences Laboratory, La Grande,OR 97850 USA.viA Technical Guide for Monitoring Wildlife Habitat

ContentsPreface. ixChapters:1. Overview.1-1Mary M. Rowland, Greg Kujawa, Bryce Rickel, and Christina D. Vojta2. Selection of Key Habitat Attributes for Monitoring.2-1Gregory D. Hayward and Lowell H. Suring3. Planning and Design for Habitat Monitoring.3-1Christina D. Vojta, Lyman L. McDonald, C. Kenneth Brewer,Kevin S. McKelvey, Mary M. Rowland, and Michael I. Goldstein4. Monitoring Vegetation Composition and Structure as HabitatAttributes.4-1Thomas E. DeMeo, Mary M. Manning, Mary M. Rowland, Christina D. Vojta,Kevin S. McKelvey, C. Kenneth Brewer, Rebecca S.H. Kennedy,Paul A. Maus, Bethany Schulz, James A. Westfall, and Timothy Mersmann5. Using Habitat Models for Habitat Mapping and Monitoring.5-1Samuel A. Cushman, Timothy J. Mersmann, Gretchen G. Moisen,Kevin S. McKelvey, and Christina D. Vojta6. Landscape Analysis for Habitat Monitoring.6-1Samuel A. Cushman, Kevin McGarigal, Kevin S. McKelvey,Christina D. Vojta, and Claudia M. Regan7. Monitoring Human Disturbances for Management of Wildlife Speciesand Their Habitats.7-1Michael J. Wisdom, Mary M. Rowland, Christina D. Vojta, andMichael I. Goldstein8. Data Analysis.8-1Lyman L. McDonald, Christina D. Vojta, and Kevin S. McKelvey9. Data Management, Storage, and Reporting.9-1Linda A. Spencer, Mary M. Manning, and Bryce Rickel10. Developing a Habitat Monitoring Program: Three Examples fromNational Forest Planning.10-1Michael I. Goldstein, Lowell H. Suring, Christina D. Vojta, Mary M. Rowland,and Clinton McCarthyA Technical Guide for Monitoring Wildlife Habitatvii

Metric Equivalents. inside front coverAppendix A. References. A-1Appendix B. Glossary. B-1Appendix C. L ist of Scientific and Common Names of Plants andAnimals Mentioned in the Text. C-1viiiA Technical Guide for Monitoring Wildlife Habitat

Preface—Monitoring MattersThe tragedy of the commons occurs when people pursue their self-interests in usinga shared resource and deplete it, thereby compromising their long-term welfare (Hardin1968). The larger the area shared, the greater the potential for tragedy. The USDA ForestService is a multiple-use Federal agency that seeks to balance multiple uses of publicresources across the Nation while protecting those resources. The agency, facing continual pressure from the public and interest groups to use public resources, has developeda planning process that includes within its framework an important step—monitoring.Monitoring the effects of resource policies and projects on the Nation’s resources is critical to maintaining the long-term health, diversity, and productivity of the public’s forestsand grasslands today and into the future. A well-designed monitoring program avoids thetragedy of the commons. This guide is an invaluable contribution to understanding how tomonitor habitats.Although designed to provide a unique national contribution to habitat monitoring,particularly regarding the condition of habitat and scale of analysis, it must be made clearthat this guide does not present population monitoring approaches, or ways to count individuals. The objectives of habitat monitoring and population monitoring are distinctly different, and it is important to keep them separate while reading. Species require habitat tosurvive. As habitat conditions improve, the long-term resilience of individuals improvesand populations become better able to resist perturbations to their ecosystems. As societyuses or extracts resources from our forests and grasslands, monitoring the effects of thoseactivities helps us determine if ecosystems are behaving as predicted. Therefore, carefullydesigned monitoring programs help us avoid ecological surprises.Human uses place stress on ecosystems in the form of, for example, policies thatcontrol wildfire (quick response and control measures) to the permitting of roads thateliminate and fragment habitat. Controlling fire by extinguishing fire starts may eventually lead to increasing fuel loads to greater than normal levels. Elevated fuel levelscould lead to catastrophic fires that destroy larger areas of forest than natural effectshave destroyed in the past. Increased human access into areas containing species that aresensitive to human presence may interrupt or lower reproduction of sensitive species.Finding a balance in use of, and access to, public resources requires monitoring programsthat provide information that is crucial to managers when they adjust their managementactions to avoid habitat damage.In addition to understanding localized human impacts, monitoring is also importantto understand the larger, ever-present stress of climate change and its constantly varyingpressure on habitats through changes in temperature and precipitation. In stable climates,managers may adjust their resource management actions with more confidence in theirpredicted outcome than in unstable climates. As climate becomes more variable, asA Technical Guide for Monitoring Wildlife Habitatix

extreme events become more frequent, and as the pace of climatic change continues totrend in one direction, it becomes critical for managers to quickly adjust their policies andactions to protect public resources that are entrusted to them. Without access to the information that is gained through habitat monitoring, it is difficult at best, if not impossible,for managers to adjust their management direction and avoid major mistakes. Withoutgood information, the probability of error increases, which, for species with sensitivehabitat requirements, may be disastrous. Monitoring is fundamental to wise stewardshipof public lands.DOUGLAS A. BOYCE, JRNational Wildlife Ecologist, USDA Forest ServicexA Technical Guide for Monitoring Wildlife Habitat

Chapter 1. OverviewMary M. RowlandGreg KujawaBryce RickelChristina D. Vojta1.1 ObjectiveInformation about status and trend of wildlife habitat1 is important for the U.S.Department of Agriculture, Forest Service to accomplish its mission and meet its legalrequirements. As the steward of 193 million acres (ac) of Federal land, the Forest Serviceneeds to evaluate the status of wildlife habitat and how it compares with desired conditions. Habitat monitoring programs provide information to meet the needs of the agencywhile fostering use of standardized, integrated approaches to produce robust knowledge.This technical guide provides current, scientifically credible, and practical protocols forthe inventory and monitoring of terrestrial wildlife habitat. Protocols include data standards, data-collection methods, and methods for detecting and monitoring changes overtime (Powell 2000).To our knowledge, this document is the first comprehensive guide to monitoringwildlife habitats. It serves a unique role by providing protocols specifically tailored tohabitat monitoring, which is especially pertinent for the Forest Service, given its role inmanaging landscapes that support a wide diversity of taxa across the major biomes ofNorth America.Protocols described in this guide address habitat monitoring for terrestrial wildlife.In the past, the term wildlife was used to denote all terrestrial vertebrates, especially gamebirds and mammals, but later was expanded to include species of conservation concern.In more recent years, the term has broadened to encompass the full array of all biota inan ecosystem (Morrison et al. 2006). In this technical guide, the term terrestrial wildlifeincludes terrestrial vertebrates and invertebrates, but managers may also find the protocolsapplicable for monitoring rare plants.Although population monitoring is a necessary and critical complement to habitatmonitoring (chapter 2, section 2.2.2), this guide does not address population monitoringper se because several excellent published resources exist on this topic. Two ForestService technical guides describe population monitoring: (1) Manley et al. (2006) provideprotocols for inventory and monitoring of populations of groups of wildlife species,using standardized Forest Service plot data to assess habitat conditions at plot sites; and1Terms indicated in bold typeface are defined in the glossary in appendix B.A Technical Guide for Monitoring Wildlife Habitat1-1

(2) Vesely et al. (2006) describe protocol development for monitoring populations ofwildlife, fish, and rare plants. Thompson et al. (1998) and McComb et al. (2010) are alsogood references for monitoring wildlife populations.The target audience for this guide is professionals (e.g., ecologists, biologists,silviculturists, and planners) charged with forest planning, project impacts analysis, andhabitat monitoring at ranger district, national forest or grassland, and regional levels. Thisguide may also benefit other agencies and organizations that want to standardize theirapproaches to wildlife habitat monitoring. Protocols and process steps in this technicalguide are recommendations, not agency requirements or policy. This guide follows national direction for inventory, monitoring, and assessment as described in Forest ServiceManual (FSM) 1940 (USDA Forest Service 2009).This first chapter describes the origins of the technical guide, business requirementsfor wildlife habitat information, key concepts of habitat monitoring, recommendedroles and responsibilities of Forest Service personnel for completing and applying theprotocols, the relation of habitat monitoring to other Federal inventory and monitoringprograms, and information about data storage and reporting related to habitat monitoring.Chapter 2 describes selection of habitat attributes for monitoring, and chapter 3 addressesplanning and design of habitat monitoring programs.Chapters 4 through 7 provide specific guidance for monitoring selected habitat attributes (e.g., vegetation structure and composition), monitoring habitat within a landscapecontext, and monitoring human disturbance agents. Chapter 8 offers recommendationsfor data analysis, whereas chapter 9 addresses data storage and reporting. Chapter 10 provides detailed examples of habitat monitoring for two individual species and a monitoringplan for a species group.1.2 Background and Business Requirements1.2.1 BackgroundA wildlife protocol development team was established in 2001, under the auspicesof the Ecosystem Management Coordination Staff in the Washington Office of the ForestService, to identify and prioritize species or groups of species that would benefit fromstandardized inventory or monitoring protocols throughout the Forest Service. This teaminitially identified the need for population monitoring protocols, which resulted in threeproducts: (1) a protocol for monitoring multiple species (Manley et al. 2006), (2) a set ofprotocols for monitoring the northern goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) (Woodbridge and Hargis 2006), and (3) a general guide for developing other population monitoring protocols(Vesely et al. 2006).The Washington Office later identified the need for national protocols to addresshabitat monitoring in support of land management planning. When wildlife habitat is1-2A Technical Guide for Monitoring Wildlife Habitat

included in a land management plan’s objectives and desired conditions, habitat monitoring is a necessary component of the plan’s monitoring program. Most national forests andgrasslands undertake habitat monitoring and would benefit from guidance on selectingkey habitat attributes for wildlife as well as standard protocols for inventory and monitoring habitat attributes at a variety of spatial scales. This technical guide provides suchguidance. It represents the best available science from a broad base of published literatureand from expertise of research scientists, ecologists, and statisticians who co-authoredindividual chapters.1.2.2 Business RequirementsSpecific business requirements of the Forest Service for standardized habitat monitoring arise from the need for information in (1) land management planning, for which struc tured monitoring can facilitate plan revisions or amendments; (2) recovery of threatenedand endangered (T&E) species and sensitive species; and (3) environmental analyses forprojects as prescribed in various laws, regulations, and policies (table 1.1). Informationneeds range from status and trends of ecological diversity to population trends in relationto habitat change for individual species or species groups. Integration of habitat monitoring with monitoring of other resources is critical for meeting agency information needswhile ensuring efficient use of funds and staffing.The habitat monitoring protocols described in this guide address additional businessrequirements of the Forest Service beyond those listed in table 1.1 and include— Improving consistency in monitoring species and species groups, as identified in theNational Inventory and Monitoring Action Plan of 2000, across all administrativeunits of the Forest Service. Integrating habitat monitoring with other ongoing data-collection activities (e.g.,Forest Inventory and Analysis [FIA] Program, intensified grid inventories, andCommon Stand Exams) for greater efficiency. Ensuring that the best available science is considered in habitat monitoring throughdocumentation of the monitoring process and consistent application and appropriateinterpretation of science. Ensuring that effects of climate change on habitat are incorporated in monitoringprograms, as appropriate, using guidance such as the Forest Service “NationalRoadmap for Responding to Climate Change” and climate performance scorecard(USDA Forest Service 2010a). Providing standardized habitat information for broad-scale assessments. Understanding effects of management actions on habitat, such as activities related tothe Healthy Forests Initiative and the Healthy Forests Restoration Act. Providing standardized habitat information for other existing or emerging national andregional business requirements, such as program and budget planning and execution.A Technical Guide for Monitoring Wildlife Habitat1-3

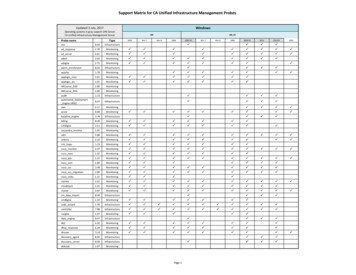

Table 1.1.—Forest Service business requirements for habitat monitoring in relation to existing laws, rules, and policies.No.Business requirementTarget groupType ofinformation neededAnalysis scaleaType of report1To provide information onVertebrates, invertebrates,habitats needed to maintain and plants whose populaviable populations of existing tions are at risknative and desired nonnativevertebrate and invertebratespecies (NFMA 1982 reg. at36 CFR 219.19)Habitat abundance,distribution, condition, and trendMid and broad scale: theplanning area, usually alocal management unit(e.g., national forest,grassland) or multipleadministrative unitsLRMP, AMS, annualmonitoring and evaluation reports, supportingregional assessments2To provide information onMIS for planning and monitoring under the 1982 rulefor the NFMAbMISHabitat condition andtrend as related topopulation change, orhabitat only (dependson specific languagein the LRMP)Mid and broad scale: theplanning area, usually alocal management unit(e.g., national forest,grassland) or multipleadministrative unitsLRMP or AMS, annualmonitoring and evaluation reports, supportingregional assessments3To aid in the recovery ofspecies listed under theESA (FSM 2670) (USDAForest Service 2005a)Federal threatened orendangered speciesAs indicated in recovery plans; typicallyhabitat trends andtrends in stressorsMid, broad, and someAnnual reports of recoverytimes national scale: geo- plans and habitat consergraphic range, significant vation strategies; BA, BOportion of range, or ESUof the listed species4To avoid Federal listing ofplant and animal species(FSM 2670, USDA DR9500-004) (USDA ForestService 2005a)Plant or animal speciesdesignated “sensitive” bythe Forest ServiceDistribution, status,and trend of habitatsMid, broad, and sometimes national scaleHabitat conservation strategies and agreements;progress reports; annualmonitoring and evaluationreports; BA, BE, projectrecords5To provide information forenvironmental analysis ofproposed projects (NEPA)TES, MIS, sensitive,socioeconomic species,and migratory birdsAvailability of suitablehabitat in the projectarea and larger landscape contextBase (local), mid, andbroad scale: usually theproject area and largerlandscape context; dependent on project scope,species affected, etc.Landscape or watershedassessment; road analysis;project EIS, EA, or CE;BE, BA, BO; post-activitymonitoring reports6To work cooperatively withStates in the conservationof selected species (as described in the Sikes Act)Species identified for conservation through an MOUbetween a State and theForest Service, includingspecies identified in Statecomprehensive wildlifeconservation strategiesInformation as specified in the MOU orstrategyA State or the range of aspecies within a StateProgress reports asspecified by the MOU7Account for the effects ofglobal climate change onforest and rangeland conditions (Forest and RangelandRenewable Resources Planning Act of 1974)Vertebrates, invertebrates,and plants whose habitatsmay be at risk from climatechangeHabitat abundance,distribution, condition, and trendMid and broad scale: theplanning area, usually alocal management unit(e.g., national forest,grassland) or multipleadministrative unitsLRMP, annual monitoringand evaluation reports,supporting regional assessmentsAMS analysis of the management situation. BA biological assessment. BE biological evaluation. BO biological opinion. CE categoricalexclusion. CFR Code of Federal Regulations. EA environmental assessment. EIS environmental impact statement. ESA EndangeredSpecies Act. ESU ecologically significant unit. FSM Forest Service Manual. LRMP Land and Resource Management Plan. MIS management indicator species. MOU Memorandum of Understanding. NEPA National Environmental Policy Act. NFMA National ForestManagement Act. TES threatened, endangered, and sensitive species.aSee chapter 4, section 4.2.4, for definition of scale as used in this guide.bMIS, a concept developed in the 1982 planning rule to implement the NFMA (USDA Forest Service 1991). The use of MIS is in effect for allplanning units until their plans are revised under a new planning rule.Source: Adapted from Vesely et al. (2006): table 1.1.1-4A Technical Guide for Monitoring Wildlife Habitat

1.3 Key Concepts1.3.1 HabitatClements and Shelford (1939) originally defined habitat as the physical conditionssurrounding a species, a population, an asse

Dan White (Big H Design, Inc.) prepared graphics; and Shelly Witt (Forest Service) created and maintained a file-sharing Web site for authors. We thank the following . Data Management, Storage, and Reporting. 9-1 Linda A. Spencer, Mary M. Manning, and Bryce Rickel 10. Developing a Habitat Monitoring Program: Three Examples from .