Transcription

J. Behav. Ther. & Exp. Psychiat. 45 (2014) 242e251Contents lists available at ScienceDirectJournal of Behavior Therapy andExperimental Psychiatryjournal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jbtepCombined group and individual schema therapy for borderlinepersonality disorder: A pilot studyVeronique Dickhaut a, Arnoud Arntz b, *abCommunity Mental Health Center Maastricht, The NetherlandsClinical Psychological Science, Maastricht University, PO Box 616, The Netherlandsa r t i c l e i n f oa b s t r a c tArticle history:Received 18 September 2013Received in revised form22 November 2013Accepted 23 November 2013Background and Objectives: Schema Therapy (ST) is a highly effective treatment for Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). In a group format, delivery costs could be reduced and recovery processes catalyzedby specific use of group processes. As patients may also need individual attention, we piloted thecombination of individual and group-ST.Methods: Two cohorts of BPD patients (N ¼ 8, N ¼ 10) received a combination of weekly group-ST andindividual ST for 2 years, with 6 months extra individual ST if indicated. Therapists were experienced inindividual ST but not in group-ST. The second cohort of therapists was trained in group-ST by specialists.This made it possible to explore the training effects. Assessments of BPD manifestations and secondarymeasures took place every 6 months up to 2.5 years. Change over time and differences between cohortswere analyzed with mixed regression.Results: Dropout from treatment was 33.3% in Year 1, and 5.6% in Year 2, without cohort differences. BPDmanifestations reduced significantly, with large effect sizes, and 77% recovery at 30 months. Large improvements were also found on general psychopathological symptoms, schema (mode) measures,quality of life, and happiness. Cohort-2 tended to improve faster, but there were no differences betweencohorts in the long term.Limitations: The study was uncontrolled, training effects might have been non-specific, and the samplesize was relatively small.Conclusions: Combined groupeindividual ST can be an effective treatment, but dropout might be higherthan from individual ST. Addition of specialized group-ST seems to speed up recovery compared to onlyindividual ST.Ó 2013 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.Keywords:CBTSchema therapyBorderline personality disorderClinical trial1. IntroductionBorderline personality disorder (BPD) is a severe mental condition, characterized by a pervasive pattern of instability in moods,interpersonal relationships, self-image and behavior. The prevalence is estimated to be 1e2% of the general population and rangesfrom 10 to 20% among outpatient and inpatient individuals treatedin mental health clinics (American Psychiatric Association, 2005).Specific structured therapies have demonstrated efficacy inreducing BPD-symptoms in randomized controlled trials, such asdialectical behavior therapy (Linehan, Armstrong, Suarez, Allmon,& Heard, 1991) and cognitive therapy (Davidson et al., 2006). Inthe last decade more comprehensive treatments which aim at fullrecovery have been tested. Various treatments seem promising.* Corresponding author.E-mail address: Arnoud.Arntz@maastrichtuniversity.nl (A. Arntz).0005-7916/ e see front matter Ó 2013 Elsevier Ltd. All rights .004Among them is Schema Therapy (ST; Arntz & van Genderen, 2009;Young, Klosko, & Weishaar, 2003). In a multicenter trial in which STwas compared to Transference Focused Psychotherapy (TFP;Yeomans, Clarkin, & Kernberg, 2002) ST turned out to have bettertreatment retention and to be more effective on various measures(Giesen-Bloo et al., 2006). ST was also more cost-effective than TFPwith lower societal costs and stronger effects (van Asselt et al.,2008). A second study demonstrated that ST can be successfullyimplemented in regular practice, and that telephone availabilityoutside office hours is not necessary (Nadort et al., 2009).The duration of ST makes the therapy expensive, and problematic to deliver to all patients requesting it. These are compellingreasons to use a group therapy format. Other advantages of grouptherapy relate to the curative factors as described by Yalom andLeszcz (2005). Among these are universality, getting and givingemotional support, modeling, sense of belonging, practicing interpersonal skills and bonding. Patients can experience the satisfaction of being helpful to others and by doing so bolster their self-

V. Dickhaut, A. Arntz / J. Behav. Ther. & Exp. Psychiat. 45 (2014) 242e251confidence. An important assumption in working with patientswith BPD in groups is that they recognize each other’s problemsfaster and easier than their own problems, and as a consequencepatients can validate, support, confront and advise one another.Moreover, patients often experience such responses by other patients as more genuine than when made by a therapist. For thesereasons, it has been argued that group-ST might “catalyze” thechange processes of ST, thus leading to faster and deeper changesthan individual ST (Farrell & Shaw, 2012; Farrell, Shaw, & Webber,2009).We developed a protocol for outpatient treatment, in which STin group was combined with individual ST. We assumed that individual treatment was essential for a number of reasons. Weconsidered individual attention and attachment a basic need of theBPD patient, and it was our opinion that trauma processing ispreferably offered in individual sessions, where specific techniquescan be used to process painful and disturbing memories, that mightbe too confronting for other group members. An additional argument is that the combination mimics natural development ofattachment with different persons (parent and peers).During the study, we learned that Farrell and Shaw (2012) haddeveloped a specialized group-ST model, of which a first RCTindicated very strong effects (Farrell et al., 2009). The group processis handled in a very specific way, which demands specific behaviorand collaboration of the therapist pair. Our therapists were trainedin their method; but the first cohort was already halfway throughtreatment and the second hadn’t started when the training tookplace. This offered us the possibility to explore whether there wereany differences between the two cohorts associated with the use ofthe Farrell and Shaw model.2. Methods2.1. PatientsPatients referred to the Community Mental Health Center ofMaastricht, with a primary diagnosis of BPD, based on the Structured Clinical Interviews for the DSM-IV, I and II (First, Gibbon,Spitzer, Williams, & Benjamin, 1997; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, &Williams, 1996; Groenestijn, Akkerhuis, Kupka, Schneider, &Nolen, 1999; Weertman, Arntz, & Kerkhofs, 2000) were asked toparticipate in the study. If they agreed, they were further screened,by using a semi-structured clinical interview, the Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index, fourth edition (BPDSI-IV) (GiesenBloo, Wachters, Schouten, & Arntz, 2010). If scores were 20,further baseline measurement took place.Inclusion criteria were: a main diagnosis of BPD, BPDSI-IV score 20, age 18e60, IQ 80 and Dutch literacy. IQ was only tested incase of doubt. Exclusion criteria were: an axis-I disorder thatgenerally needs primary treatment. These were psychotic disorder(except short reactive psychotic episodes belonging to BPD), manicepisodes, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), addiction of such severity that detoxification was indicated (other addictions were not excluded), anorexia nervosa, autistic disorder.Also 2 Narcissistic or 2 Antisocial PD traits were exclusioncriteria, as these are likely to be disruptive to BPD group treatment.Males were excluded if they would be the only one in the group.Eighteen women with a primary diagnosis of BPD were included(see Fig. 1 for the consort flow diagram).2.2. Outcome measures/assessmentThe primary outcome measure was the score on the BPDSI-IV, aDSM-IV based semi-structured interview that assesses frequencyand severity of BPD manifestations during the last 3 months (Arntz243et al., 2003; Giesen-Bloo et al., 2010). The interview is appropriatefor repeated measurements and therefore for treatment evaluation.This instrument shows excellent psychometric properties (Cronbach’s alpha ¼ .85 in a BPD sample, .96 in a heterogeneous sample;interrater reliability .99; excellent validity and sensitivity tochange). The BPDSI has a cut-off score of 15 between patients withBPD and controls, with a specificity of .97 and a sensitivity of 1.00(Giesen-Bloo et al., 2010). The recovery criterion was thereforedefined as achieving a BPDSI-IV score of less than 15 and maintaining this score until the last assessment. An independentresearch assistant, trained in the BPDSI, administered the BPDSI-IV.Secondary outcome measures were the following self-reportinstruments. The BPD-checklist inquires for someone’s experienced burden of BPD complaints during the last month (GiesenBloo, Arntz, & Schouten, 2006). It is complementary to the BPDSIIV in the way that it reflects the patients’ experienced change,where the BPDSI-IV examines the persons’ objective change on BPDsymptomatology. The SCL-90 (Derogatis, Lipman, & Covi, 1973)measures subjective distress from a range of psychopathologicalsymptoms. Quality of Life was assessed with the mean WhOQoLGroup: Development of the World Health Organization (1998),short version item score, and the thermometer scale of the EuroQoL(range 0e100; Brooks 1996), which assesses primarily subjectivephysical health state. Happiness was assessed with the 1-itemhappiness question validated in more than 30 countries, with thefollowing response possibilities: (1) completely unhappy; (2) veryunhappy; (3) fairly unhappy; (4) neither happy nor unhappy; (5)fairly happy; (6) very happy; (7) completely happy (Veenhoven,2008). ST-specific measures were the Young Schema Questionnaire (YSQ; Rijkeboer, van den Bergh, & van den Bout, 2005; Young& Brown, 1994) of which the total score was used; and the SchemaMode Inventory (Lobbestael, van Vreeswijk, & Arntz, 2008;Lobbestael, van Vreeswijk, Spinhoven, Schouten, & Arntz, 2010),of which the mean item score of dysfunctional modes and the meanitem score of functional modes was used.2.3. Treatment and therapistsThe treatment protocol consisted of weekly 90-min group sessions led by two therapists, combined with weekly 1-h individualsessions. For pragmatic reasons, group therapists did not have to bethe same as the individual therapists. After the first year, the frequency of individual sessions could diminish when therapist, peersupervision group and patient agreed. Individual sessions followedthe Arntz and van Genderen (2009) protocol and had the specificaim to support group sessions (e.g., to help with problems patientshad in dealing with the group), to deal with crises, and to doextensive trauma processing.Before group therapy started, some individual sessions wererequired. In these sessions case conceptualizations in terms of themode model were made. Patients were prepared by addressingworries patients had about the group. The number of pretherapeutic sessions differed per patient, from 2 to 12 sessions.Treatment integrity was monitored by means of peer supervision.Therapists were all experienced schema therapists, but none ofthem had any experience with doing group-ST.The treatment protocol addressed the theoretical model of ST,different phases of (group) therapy, and ST techniques. Central tothe theoretical model of ST in working with BPD is the assumptionof 6 schema modes. The distinguished modes in BPD are vulnerable(abandoned/abused) child, angry/impulsive child, punitive parent,detached protector or any other protective mode, and the functional healthy adult and happy child modes. Schema modes are setsof schemas expressed in pervasive patterns of thinking, feeling andbehaving. Important goals of ST are to show empathy with and

244V. Dickhaut, A. Arntz / J. Behav. Ther. & Exp. Psychiat. 45 (2014) 242e251Fig. 1. Patient flow chart.protect the Vulnerable Child, to challenge the Punitive Parent, to setlimits to the Angry/Impulsive child, to reassure the Protectivemode, to enhance the Healthy Adult and promote expression of theHappy Child.Group treatment was time-limited to 2 years. To ensure safetyno additional patients were introduced after the first session andstructure was maintained on a high level. Sessions did not have anestablished program, but every week a session plan was made,depending on the process of the group and individual patients.Main goal for the first stage of treatment was mutual understanding, bonding and cohesion; and to get acquainted with themode model and the corresponding language. In the working phasemore and more behavioral, cognitive and experiential techniqueswere introduced. The aim of the last phase was preparing for the

V. Dickhaut, A. Arntz / J. Behav. Ther. & Exp. Psychiat. 45 (2014) 242e251end of and the future without the group. If necessary, individualsessions were continued after 2 years.Group therapists of the first group-ST started without trainingfor working in ST groups. After 9 months of treatment, all involvedtherapists received a three day (20.5 h) training by Farrell and Shaw(2012), Farrell et al. (2009), who had more than 20 years of experience with group-ST. Farrell and Shaw developed a therapeuticstyle and collaboration between therapists to optimally conduct STin group format. They stress the need to focus on and balance theindividual needs of each participant and the collective need of thegroup, similar as a parent would for a group of siblings. As aconsequence of the training, therapists’ style changed, and newtherapeutic techniques were used. Most important changes were:stressing the communality between group members and supportthe connection between group members by constantly broadenconversation (instead of working individually in front of the group),clear division of roles between the therapists (with at least onetherapist taking care that all patients stay involved), enhancingsecurity by setting clear rules and limits, offering more structure insessions, de-escalate in times of crisis, providing written information and psychoeducation, giving homework assignments andpaying more attention to the happy child mode.The group therapists of the second group-ST started right afterthis training and used the Farrell and Shaw format. The therapists ofthe first group reported only limited success in changing style andmethods. Group and individual therapists of both cohorts hadweekly peer supervision and no expert supervision. There was nodifference between cohorts in amount of peer supervision.All group members participated in the study and if patientswanted to quit group therapy, individual ST stopped. If desired,patients could in that case be referred to another treatment.2.4. Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis was based on the intent-to-treat principle, using all available data from all participants that startedtreatment. We used mixed regression for longitudinal data as thismethod can deal with missings and yields more valid estimates ofeffects than analyzing completers only or using last observationcarried forward imputation (Schafer & Graham, 2002). The six 6months assessments during 2.5 years constituted the repeatedmeasure (i.e., time); and fixed factors/covariates were cohort, time,cohort by time interaction. Any variable significantly different between cohorts at baseline was planned to be added as additionalcovariate. We assessed linear, quadratic and cubic time trends(except for the analysis of recovery, see below).We first checked the distribution of the data. One case hadextreme scores on baseline BPDSI and BPD-checklist, creatingoutliers. These were pulled in to 2 SD, and remained the highestscores. No further serious deviations from normal distribution wereobserved. Next differences at baseline between cohorts wereexamined. Groups differed significantly on baseline WHOQoL andEuroQoL thermometer (Table 2), thus these were considered ascovariates. However, EuroQoL baseline didn’t contribute to thediscrimination between groups after WHOQoL baseline (thestrongest predictor) was entered in a logistic regression, thereforeonly the (centered) WHOQoL baseline score was used as covariate.Recovery, defined by BPDSI score 15 (Giesen-Bloo et al., 2010)was analyzed by mixed logistic regression. Complex covariancestructures of the repeated measures part led to estimation problems; therefore a simple compound symmetry model was used, withrandom intercept. As analyses with time modeled as a dimensionalcovariate failed to converge, time was included as a factor with 6levels (assessments as levels). Addition of the WHOQoL baseline aspredictor also led to estimation problems, the covariate was245therefore not included. Thus, the fixed part consisted of intercept,group, assessment, and group by assessment interaction.Dimensional outcomes were analyzed with an unstructuredcovariance structure for the repeated measures part (being the bestfitting). For the fixed part, intercept, centered group, centered WHOQoL baseline, time trends (linear, quadratic and cubic) and group bytime trends were analyzed. For the WHOQoL analysis, the baseline wasleft out of the analysis as WHOQoL baseline was already covariate.When p .10, interactions were deleted from the model, in hierarchical order: first cubic, then quadratic, then linear time trend group.Effect sizes were reported as r ¼ O(t2/(t2 þ df)) for the mixed regressionoutcomes, and for the conventional treatment effects from baseline tolast assessment (30 months) as Cohen’s d ¼ mean change/SD, withmean change derived from the mixed regression estimates and pooledbaseline SD as numerator (Feingold, 2009).3. Results3.1. Patient accrualThe consort diagram is presented in Fig. 1. Thirty-nine patientswere referred after intake and informed about the study. Twentyone were excluded (14 patients after initial contact, 7 after thecomplete screening procedure). Nine patients declined participation (5 patients felt not being able to commit themselves to a 2 yearperiod of therapy, 4 did not want to have therapy in a group), 3 didnot meet inclusion criteria (2 had BPDSI-IV scores 20 and 1 hadonly 4 traits on BPD), 2 met exclusion criteria (1 had ADHD and 1had 3 narcissistic traits on SCID II), 5 had the intention to start butexperienced practical impediments that made participationimpossible, such as moving to another city, or inconvenient time ofgroup sessions, and 1 was male, and was excluded because hewould be the only male patient in group. One patient knew one ofthe group therapists privately, which made it not possible toinclude her. Eventually 18 patients participated in the study.The first cohort consisted of 8 patients. In the first week 1 patient dropped out of treatment, after 11 weeks a second patientquit. For a long time the first group consisted of 6 patients. Afteralmost one and a half year a last patient dropped out, because shewent to university and could not attend group sessions anymore.The second cohort started treatment 9 months later. This cohortconsisted of 10 patients. Within the first 6 months 4 patientsdropped out for various reasons, like too much anxiety, too muchturbulence in daily life or expected rejection and punishment by(immigrant) family if patient would reveal being in treatment. Thedifference in dropout (group 1: 37.5%, group 2: 40%) was not significant, Fisher’s exact test p ¼ 1.00.3.2. Treatment groups at baselineTable 1 gives an overview of the main patients’ characteristics atbaseline. Patients were all female, mainly in their 20s and 30s andwith average educational levels. There were no significant differences between the two cohorts in these variables. Table 2 providesan overview of differences between the groups on outcome parameters at baseline. As can be seen, WHOQoL and EuroQoL thermometer differed significantly between groups at baseline. TheWHOQoL was used as covariate to correct for this (the EuroQoLbeing redundant as extra covariate).3.3. Primary outcome3.3.1. RecoveryUsing the BPDSI 15 criterion, recovery rates by group andassessment were estimated by means of mixed logistic regression.

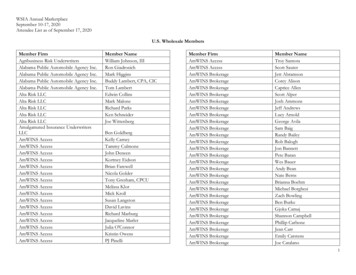

246V. Dickhaut, A. Arntz / J. Behav. Ther. & Exp. Psychiat. 45 (2014) 242e251Table 1Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of starters.aTreatment group (N ¼ 18)Age, mean (SD)EducationGraduate (WO en HBO)Some college (LBO, MBO)High school graduate (MAVO, HAVO, VWO)Grades 7e11Employment chotropic medication use at baselineRecent suicide planning, steps or attemptsbRecent nonsuicidal self-injurycNumber of Axis I diagnosesNumber of Axis II diagnoses (incl. BPD)No. of patients who had previous treatmentabc28.5 (8.7) Range: 19e462691(11.1)(33.3)(50.0)(5.6)1 (5.6)5 (27.8)4 (22.2)4 (22.2)4 (22.2)13 (72.2)7 (38.9)10 (55.6)2.381.897 (4 patients had 2 and 3patients had 3 previoustreatments)Data are given as number (percentage) except where otherwise indicated.According to BPDSI-IV items 5.11e5.13 in the previous 3 months.According to BPDSI-IV items 5.1e5.8 in the previous 3 months.Fig. 2 presents the estimated proportions. At 24 months, immediately after the group treatment finished, the proportions differedsignificantly, F(1,65) ¼ 4.07, p ¼ .048, with the second group havinga higher proportion of recovered patients (66.5% (95%CI [29.2,90.5]) vs. 18.7% (95%CI [2.8, 65.1])). At FU the difference disappearedand the estimated recovery was 77.4% (95%CI [45.9, 93.3]), that is 14out 18.3.3.2. BPDSI total scoreMixed regression revealed significant linear, squared and cubictime effects (Table 3). There was a trend toward a significant groupby cubic time effect (p ¼ .052), reflecting the relatively slowerreduction of BPDSI scores in group 1, and the quick reduction tosimilar BPDSI levels after the group was finished as in group 2(Figs. 2 and 3). Cohen’s d was 23.14/8.50 ¼ 2.72 for change frombaseline to last observation (average of both groups).3.4. Secondary outcomes3.4.1. BPD-checklistAfter deleting the cubic time by group interaction (p .10),mixed regression revealed significant linear, squared and cubictime effects, a significant group by quadratic time effect, and atrend toward a group by linear time effect (Table 3). The interactions reflect the relatively slower reduction in BPD-checklistTable 2Baseline values of outcome variables of the two roQoL thermometerWHOQoLSMI dysfunctionalSMI functionalYSQ totalM (SD)Group 1Group pt ¼ .27t ¼ .14t ¼ .92t ¼ 1.53U ¼ 54t ¼ 2.19t ¼ .05t ¼ 1.05t ¼ .50.79.89.37.15.049.043.96.31.62Note. t ¼ t-value of t-test with df ¼ 16; U ¼ U-value of ManneWhitney test.Fig. 2. Estimated proportions recovered participants by group from mixed logisticregression. At 24 months (posttest) the groups differed significantly, F(1,65) ¼ 4.07,p ¼ .048.scores in group 1 during months 6e24, which disappeared at 30months (Fig. 2). Cohen’s d was 51.72/22.06 ¼ 2.34 for change frombaseline to last observation (average of the two groups).3.4.2. SCL-90Mixed regression revealed significant interactions of quadraticand cubic time trends with group, reflecting the relatively slowerreduction in BPD-checklist scores in group 1 during months 6e24,which disappeared at 30 months (Fig. 2, Table 3). Cohen’s d was89.79/60.42 ¼ 1.49 for change from baseline to last observation(average of the two groups).3.4.3. HappinessMixed regression revealed that the cubic time trend by groupinteraction was n.s. (p ¼ .39). The results after deleting this interaction from the model showed significant linear, quadratic andcubic time effects, as well as a significant quadratic time by groupinteraction (Table 3), reflecting quicker increase in happiness ratings in group 2 (Fig. 2). Cohen’s d was 2.07/1.17 ¼ 1.77 for changefrom baseline to last observation (average of the two groups).Veenhoven (2008) reports Dutch general population norms: amean of 5.28 with SD ¼ .83. This implies that at last observationparticipants fell on average well in the normative range (mixedregression estimated mean ¼ 5.23), and individual estimatesshowed that all fell within the 95% CI of the population norms.3.4.4. EuroQoL thermometerAfter deleting the n.s. group by cubic and quadratic time interactions, mixed regression revealed a significant group by lineartime interaction, next to the main time effects (Fig. 2, Table 3). Asbaseline WHOQoL was n.s. (p .20) the covariate was deleted fromthe model (inclusion led to highly similar results). The secondgroup had a significantly stronger increase in thermometer ratings.As conditions differed at 30 months, separate effect sizes of thechange with respect to baseline were calculated: group 1 d ¼ 4.66/13.44 ¼ .35; group 2 d ¼ 20.41/13.44 ¼ 1.52 (average d ¼ .94).3.4.5. WHOQoLAfter deleting the group by cubic time trend interaction and themain cubic time effect (p’s .10), significant group by quadratic andgroup by linear time trend interactions were found (Table 3). As

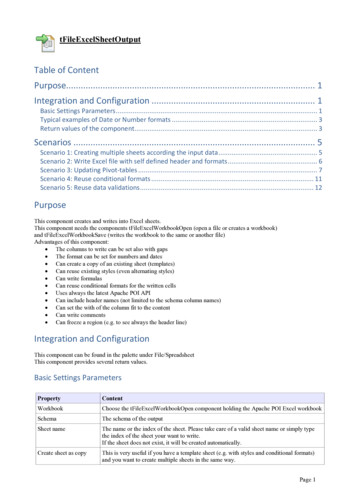

V. Dickhaut, A. Arntz / J. Behav. Ther. & Exp. Psychiat. 45 (2014) 242e251247Table 3Results of mixed regression analyses.Variable effectBPDSIInterceptWHOQoL blGroupTime linearTime quadraticTime cubicGroup Time linGroup Time quaGroup Time cubBPD-checklistInterceptWHOQoL blGroupTime linearTime quadraticTime cubicGroup Time linGroup Time quaSCL-90InterceptWHOQoL blGroupTime linearTime quadraticTime cubicGroup Time linGroup Time quaGroup Time cubHappinessInterceptWHOQoL blGroupTime linearTime quadraticTime cubicGroup Time linGroup Time quaEuroQoL ThermometerInterceptGroupTime linearTime quadraticTime cubicGroup Time linWHOQoLInterceptWHOQoL blGroupTime linearTime quadraticGroup Time linGroup Time quSMI dysfunctional scalesInterceptWHOQoL blGroupTime linearTime quadraticGroup Time linGroup Time quSMI functional scalesInterceptWHOQoL blGroupTime linearTime quadraticTime cubicGroup Time linGroup Time quYSQ total scoreInterceptWHOQoL blGroupTime linearEstimate95% CIS.E.33.43 6.922.80 13.644.98 .643.17 2.75.4630.20; 36.67 10.06; 3.77 4.30; 9.89 17.32; 9.963.34; 6.63 .86; .41 4.21; 10.54 6.05; .56.004; .921.501.413.341.64.71.103.281.42.20114.84 16.3316.08 35.8814.88 1.96 11.932.70109.60; 21.55;5.56; 48.61;8.75; 2.74; 24.80;.00;120.07 11.1126.60 23.1521.02 1.17.945.40235.06 39.724.66 33.3213.74 2.1355.33 39.696.07216.81; 44.88; 32.01; 66.56; 2.31; 4.32; 11.15; 71.81;1.70;253.31 34.564134 .0829.80.05121.81 7.5710.433.211.06 .181.50 .66.09.34 .102.88;1.03; .84;.68; 1.05;.04; .39; .20;56.837.7713.19 6.73.923.1550.12; 1.76;2.48; 13.48; .07;2.25;tdfpr22.31 4.91.84 8.337.04 6.35.97 1.932.2813.139.8215.459.437.738.259.377.628.10 .001.001.42 .001 .001 .875.582.70.355.771.1752.30 10.284.16 6.435.51 5.67 2.072.306.722.844.228.538.838.869.938.14 .001.002.013 .001 .001 5.037.30.9930.0614.601.9727.49 19.13.27 2.221.88 2.171.84 53 .001 49.63.693.551.10.472.33 .26.141.07 .01.16.02.31.38.18.02.33.0420.6267.36 .593.94 3.583.671.04 2.4116.017.0616.1012.9012.5512.3510.5410.43 .001 7.191.752.64 2.142.017.8616.5014.3014.2213.8113.699.49 .001.10.019.050.065 .001.98.42.57.50.48.932.14.19 .12 .06.03.39 .081.91; 2.37.003; .38 .64; .40 .21; .10 .003; .05.08; .71 .13; .02.10.09.24.07.01.14.0220.742.24 .50 .782.422.75 3.2110.7410.8414.5911.4611.5311.4611.53 0 .42.39 .10 .01 .44.092.88; .68; .14; .23; .03; .69;.04;3.33 .16.91.02.01 .19.13.11.12.25.06.01.11.0228.76 3.511.56 1.82 .87 3.954.4514.1613.7415.1610.199.8310.179.80 7.49 .22.55 .20.03.20 .062.81; 3.13.33; .64 .57; .13.09; 1.01 .43; .03 .002; .06 .18; .58 .12; .008.07.07.16.21.10.01.17.0339.786.92 1.332.59 1.962.051.16 1.9213.1611.4014.7712.2411.1710.6011.3011.48 .001 491.341.503.091.7832.36 5.111.76 2.8714.8614.6215.8010.57 .001 .001.097.016.99.80.41.6643.86 7.645.44 5.1040.29; 10.84; 1.11; 9.04;46.13 4.4511.99 1.16(continued on next page)

248V. Dickhaut, A. Arntz / J. Behav. Ther. & Exp. Psychiat. 45 (2014) 242e251Table 3 (continued )Variable effectTime quadraticTime cubicGroup Time linGroup Time quGroup Time cuEstimate1.61 .252.04 2.77.4795% CI.004; 3.22 .42; .07 5.83; 9.92 5.98; .45.13; .82S.E.72.083.561.44.15tdf2.24 3.18.57 .58.72.17.53.70Note. Effect size r ¼ O(t2/(t2 þ df)); WHOQoL bl ¼ centered baseline WHOQoL covariate; lin ¼ linear; qu ¼ quadratic; cu ¼ cubic.Fig. 2 shows, this reflected the initially stronger increase in WHOQoL scores in the second group, compared to the first group.Treatment effect size based on the average effect of the two groupswas d ¼ .53/.405 ¼ 1.31.3.4.6. Schema Mode Inventory e dysfunctional modesAfter deleting the cubic time trend effects with p .10, the interactions of linear and quadratic time trends with group weresignificant, Table 3. As is shown in Fig. 2, the reduction indysfunctional schema mode scores took place earlier and faster inthe second group, as compared to the first group. The treatmenteffect size based on the average effect of the two groups wasd ¼ .72/.62 ¼ 1.16.3.4.7. Schema Mode Inventory e functional modesAfter deleting the cubic time trend by group interaction withp .10, a trend toward significance in the quadratic time by groupinteraction emer

Schema therapy Borderline personality disorder Clinical trial abstract Background and Objectives: Schema Therapy (ST) is a highly effective treatment for Borderline Person-ality Disorder (BPD). In a group format, delivery costs could be reduced and recovery processes catalyzed by specific use of group processes.