Transcription

ACLU AND PHR RESEARCH REPORTBehind Closed DoorsAbuse and Retaliation Against Hunger Strikers inU.S. Immigration DetentionBehind Closed Doors1

ACLU AND PHR RESEARCH REPORTBehind Closed DoorsAbuse and Retaliation Against Hunger Strikers inU.S. Immigration Detention 2021 AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNIONAND PHYSICIANS FOR HUMAN RIGHTSCover Photo AP/David Goldman

AcknowledgementsWe are indebted to the courageous former hungerstrikers who shared their stories with us. We standwith the many other current and former hungerstrikers protesting detention and mistreatment byImmigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Thisreport would not have been possible without them.Lead WritersEunice Hyunhye Cho, ACLU National Prison Project(ACLU-NPP); Joanna Naples-Mitchell, Physicians forHuman Rights (PHR)Contributing WritersRanit Mishori, PHR; Matthew Wynia, PHR AdvisoryCouncil; John Andrews, Katherine C. McKenzie,Sumaiya Sayeed, Yale Center for Asylum Medicine(YCAM)Research InterviewsEunice Hyunhye Cho, ACLU NPP; Kathryn Hampton,Joanna Naples-Mitchell, PHR; Farzana Ali, PHR internFOIA LitigationCarl Takei, ACLU, formerly of the ACLU NationalPrison Project, who conceived of the underlying FOIArequest and litigation on behalf of hunger strikes; DavidSobel and Arthur Spitzer, ACLU DC, who litigated theunderlying FOIA requestInitial Document ReviewHajar Habbach, Kathryn Hampton, Joanna NaplesMitchell (cross-checking), Elsa Raker, PHR; FarzanaAli, Manuela Arroyave, Thomas Blecher, EstherChoo, Liza Roychowdhury, Irene Hwang, JuliaKepczynska, Riyana Lalani, PHR internsBackground ResearchEsther Choo, Liza Roychowdhury, Riyana Lalani,PHR interns; Lani Galloway, Lucia Geng, AnitaYandle, Sloan Wilson, ACLU internsLegal ResearchFarzana Ali, Irene Hwang, Julia Kepczynska, PHRinterns; Maddy Gates, ACLU internMedical Literature ReviewRanit Mishori, PHR; John Andrews, Katherine C.McKenzie, Sumaiya Sayeed, YCAMReport ReviewersKathryn Hampton, Michele Heisler, Ranit Mishori,Karen Naimer, Claudia Rader, Elsa Raker, SusannahSirkin, Raha Wala, PHR; Jamil Dakwar, David Fathi,Tamara Gregg, Emily Greytak, Hanna Johnson,Michael Tan, Naureen Shah, ACLU; Matthew Wynia,PHR Advisory Council; John Andrews, Katherine C.McKenzie, Sumaiya Sayeed, YCAM; Farzana Ali, PHRintern; Lani Galloway, ACLU NPP intern; John Otieno(pseudonym), former hunger strikerExternal PartnersElizabeth Castillo, Setareh Ghandehari, Silky Shah,Detention Watch Network; Sarah Gardiner, Freedom forImmigrants, Margaret Brown Vega, Advocate Visitorswith Immigrants in Detention (AVID), for reviewingportions of the report; Katrina Huber, JenniferFriedman, Daniella Ponet, Diego Sanchez, Lisa Knox,for referring cases; Pablo Stewart, Parveen Parmar,Chris Benoit, for early consultations; Thomas ScottRailton, Bronx DefendersDesignPatrick MoroneySpecial thanks to:David Fathi, ACLU NPP; Emily Greytak, ACLU; HannaJohnson, ACLU Communications; Claudia Rader, KarenNaimer, PHR; Vincent Iacopino, Phelim Kine, TamarynNelson, formerly PHR; Farzana Ali, Noora Shuaib, PHRinterns; Jose Romero and Carolina Bautiza-Velez forinterpretation and translation support

ContentsExecutive Summary. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5Background. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12ICE Hunger Strike Protocols and Related Detention Standards. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18Involuntary Medical Procedures: A Primer. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21Legal and Medical Ethics Frameworks. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24Findings. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28Force-Feeding. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30Forced Hydration and Involuntary Medical Procedures. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35Role of Health Professionals in Abuses. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36Solitary Confinement and Segregation Without Medical Justification. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40Retaliatory Transfer and Deportation of Hunger Strikers, Despite Medical Risks.4 4Excessive Force. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48Mistreatment of Hunger Strikers in Family Detention. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49Other Retaliatory Measures. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51Insufficient Access to Interpreter Services. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53ICE Efforts to Break the Hunger Strike. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55Conclusion and Recommendations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59Methodology. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63Appendix I: Glossary of Acronyms. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65Appendix II: Tables of Court Orders and Medical Declarations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66Endnotes. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68

Executive SummaryAfter some time, the medical staff began to force-feed John Otieno.* “They put me ona bed and handcuffed me to an emergency medical stretcher,” he said. “[They] strapyou on the chest, waist, legs, [with] hard restraints there is no point in fighting backbecause you are there with six male, strong officers, and three nurses, and there isnothing you can do.” The doctor claimed to have a judicial order but declined to show itto him. Mr. Otieno saw two other hunger strikers who were also force-fed.Mr. Otieno, an asylum seeker from East Africa, is oneof the many people in U.S. Immigration and CustomsEnforcement (ICE) detention who began a hungerstrike to protest poor conditions and seek releaseduring the COVID-19 pandemic. Rather than listen tohis pleas, ICE retaliated by locking him in a freezingcold room, force-feeding him through a nasogastrictube against his will, and transferring him to threedifferent facilities. Only after subjecting him to all ofthis did ICE finally release him from detention in late2020. Mr. Otieno, who lost 28 pounds and now takesmedication for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)and depression, described it as “an experience that Iwouldn’t wish on my worst enemy.”The decision to begin a hunger strike in immigrationdetention is not taken lightly. A detained person’srefusal to eat may be the last option available to voicecomplaint, after all other methods of petition havefailed. Detained and imprisoned people worldwidehave engaged in hunger strikes to plead for humaneconditions of confinement or release from captivityand to bring attention to broader calls for justice.Each day, the United States government unnecessarilylocks up thousands of people in civil immigrationdetention, including children, in over two hundredimmigration detention centers around the country.1DOCUMENT 1Detainee letter, released by Immigration and CustomsEnforcement to ACLU under the Freedom of Information Act.People may be locked up for many months — evenyears — as they await final adjudication of theircases or deportation. Trapped in a system markedby mistreatment and abuse, medical neglect, andthe denial of due process, hundreds of people inimmigration detention engage in hunger strikes as ameans of protest each year. ICE’s failure to providesafe and humane conditions in detention during theCOVID-19 pandemic has only raised the stakes fordetained people. Although some detained people, on* pseudonymBehind Closed Doors5

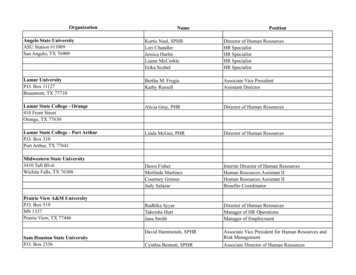

occasion, are able to bring outside attention to theirhunger strikes, very little is known of ICE’s systemicresponse to hunger striking detainees.This report provides for the first time an in-depth,nationwide examination of what happens to peoplewho engage in hunger strikes while detained by ICE.Data and MethodsThe report and its findings are based on anassessment of over 10,000 pages of documents,including emails, case records, proceduraldirectives, and court filings obtained under theFreedom of Information Act (FOIA), related tohundreds of hunger strikes in ICE detention from2013 to 2017, spanning both the Obama and Trumpadministrations.2 These include hunger strikes byat least 1,378 people from 74 countries across 62immigration detention centers in 24 states.3 Thereport is also based on a review of ICE’s currentpolicies on hunger strikes in detention and oninterviews with six formerly detained people whoengaged in hunger strikes.Force-Feeding and OtherInvoluntary MedicalProcedures: ICE’s Dangerousand Unethical Approach toHunger StrikesThe released records reveal that ICE has chosen toemploy involuntary medical procedures on detainedhunger strikers that violate ethical guidelines formedical personnel, including force-feeding, forcedhydration, forced urinary catherization, involuntaryblood draws, and use of restraints. These recordsconfirm that ICE began seeking, obtaining, andexecuting orders for involuntary treatment yearsearlier than was previously known. The documentsreveal a previously unknown force-feeding casefrom 2016 and government motions for involuntarymedical procedures as early as 2012.6ACLU and PHR Research ReportThe report andits findings arebased on anassessment ofover 10,000 pagesof documents .[relating to] hungerstrikes by at least1,378 people across62 immigrationdetention centersin 24 states.Force-feeding and forced hydration are medicalprocedures where food, nutrients, or fluids areadministered to those in detention against their willvia several invasive and painful procedures. Theseinvasive procedures include: Force-feeding via nasogastric (NG) tube: aplastic tube is inserted through one of the nostrilsand advanced through the back of the throat andthe esophagus to the stomach. This can be a verypainful procedure that causes gagging, skin andtissue irritation, and in rare cases, perforationof vital organs. The tube can also be misdirectedand advanced into the airways instead of theesophagus, potentially causing serious infections.When officials insert an NG tube against aperson’s will, they typically must forcibly restrainthe individual by staff or via mechanical restraints. Forced hydration: intravenous and PICC(peripherally inserted central catheter) lines arethe most common means of providing hydrationand parenteral nutrition. In both procedures, soft

tubes are inserted into a vein in the arm, leg, orneck via needles. The procedures can cause localpain and bleeding, can cause damage to bloodvessels, and increase risk of infections and othercomplications. Forced urinary catheterization: a tube isinserted into the urethra (the orifice throughwhich urine travels out of the body). Whencooperation or consent is not obtained, physical orchemical restraints have been used. Regardless ofwhere a catheter is inserted, the risks include localinjuries, pain, bleeding, infection, and damage tosurrounding structures, including vital organs.Involuntary medical procedures like force-feedinghave been condemned by the American MedicalAssociation as a violation of the “core ethical valuesof the medical profession” and described as cruel,inhuman, or degrading treatment or even torture byinternational human rights bodies and observers.4As ethical guidelines for medical professionalshave long recognized, participation in a hungerstrike is not a medical condition, but rather, apolitical decision by the hunger striker, and peoplecontemplating or undertaking a hunger strike areentitled to a relationship of trust with the healthprofessionals providing their care.In some instances, ICE used private prison medicalstaff to force-feed hunger strikers within a detentionfacility after nearby medical facilities refused to doso. In one instance at the Aurora Detention Centerin Colorado, ICE officials could not find any localhospital staff who would agree to force-feed a hungerstriker, due to ethical prohibitions. ICE officialsfinally turned to medical officers employed by theGEO Group, Inc., the private prison company thatoperated the detention facility, who offered to forcefeed the hunger striker.As noted in several court proceedings, ICE failedto consider alternatives to force-feeding, includingresolving hunger strikers’ basic requests forimproved conditions. In some cases, governmentattorneys sought—and received—force-feedingorders based on minimal evidence, sometimeswithout any specific detail or reference to theindividual they sought to force-feed. Detainedhunger strikers faced overwhelming challengesin defending themselves against force-feedingorders by ICE. In almost every instance weanalyzed, detained hunger strikers lacked legalrepresentation to defend themselves against thegovernment’s pursuit of force-feeding orders.ICE’s treatment of hunger strikers endangers lives.Since 2017, at least three former hunger strikers—Kamyar Samimi, Amar Mergensana, and RoylanHernandez-Diaz—have died in detention, raisingserious questions about medical neglect, lack ofmental health services, and abuse during and aftertheir hunger strikes.5 ICE’s failure to monitor peopleafter they end their hunger strike may endanger andput them at risk of refeeding syndrome, a serious andpotentially fatal complication. Refeeding syndromeis broadly characterized by metabolic abnormalitiesand severe electrolyte disturbances, leading to organdysfunction, and respiratory and cardiac failure.6Solitary Confinement andUnlawful Retaliation AgainstHunger StrikersThese records also reveal that ICE routinely placedhunger strikers in solitary confinement, which oftenamounts to cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment,and, under certain conditions, even torture.Although ICE claims that its policy to isolate hungerstrikers is for the detained person’s well-being, thereis no medical reason to place a hunger striker insolitary confinement, which can lead to additionalserious physical and mental health consequences.Placing detained hunger strikers in isolation as aresult of their protected expressive conduct alsoviolates the First Amendment. Compoundingthe harm, ICE also subjects hunger strikers whohave concomitant mental illnesses to the sameabusive solitary confinement policies. Conditions insolitary confinement units included impermissiblepunitive measures, such as cutting off water fortoilets, washing, and drinking, which is contrary toBehind Closed Doors7

ICE’s medical guidelines and of particular danger todetainees on hunger strikes.ICE’s response reveals striking inflexibility tothe underlying requests made by detained hungerstrikers. ICE’s records, news reports, and interviewswith former hunger strikers reveal numerousexamples of unlawful retaliation by ICE, includinginvoluntary transfer and excessive force. As oneofficial at the Yuba County Jail in California, whichdetains immigrants for ICE, instructed: “movehim to [another facility] and he will likely beg tocome back here and mind his manners until he isremoved.” In some instances, ICE moved to transferor deport hunger strikers despite their physical ormental vulnerability and need for continued medicalmonitoring.Separating Families, HidingStories: ICE’s Treatment ofHunger Strikers at FamilyDetention CentersOther documents reveal how ICE officials tookpains to hide hunger strikes from public view,including those at family detention centers thatdetain immigrant children and their parents. Whilediscussing a hunger strike by several mothers at thePsychological Coercion: ICE’sAttempts to End Hunger StrikesThese records and interviews with formerly detainedhunger strikers also shine a light on the many formsof day-to-day psychological coercion ICE employsto try to break hunger strikes, including denyingaccess to basic privileges, restricting water access,and threatening prosecution. ICE officers useddehumanizing language to describe hunger strikers.In one instance an officer noted, “I really feel that weshould stop neglecting these poor innocent fruit flies.I mean really, why should they have to go withoutfruit? Maybe a protest is in order.” While ICE officerswere unwilling to consider hunger strikers’ requests,they often attempted to leverage traditional foods(such as curry dishes or Bengali tea) or members ofthe hunger strikers’ faith communities to pressurethem to break their fast. In one alarming case, ICEreportedly brought in a Bangladeshi consular officialto meet with hunger striking asylum seekers who hadfled persecution by the Bangladeshi government.8ACLU and PHR Research ReportCommunity members protest to shut down the Berks Family ResidentialCenter in Leesport, Pennsylvania.Photo AP/Manuel Balce CenetaBerks Family Residential Center in Pennsylvania,an ICE physician noted that “we are using the foodprotest (or meal refusal) label rather than hungerstrikes for a couple of reasons. Since this is a familyfacility, we don’t want the messaging going out thatthere is a hunger strike going on. The optics just lookbad. Then people wonder if the kids are on strike tooand starving.” The same physician proposed familyseparation as a response to the strike: “If it appearsthey really are on a hunger strike, we will need toseparate the mother and children—send mom to an

“You cannotcompare beingin immigration[detention]; it's likesomething out of ahorror story.”IHSC [ICE Health Service Corps] facility to addressthe hunger strike.”In other instances, documents revealed that ICEofficials recommended misrepresentation oromission of key facts related to hunger strikes toevade oversight reporting requirements. In one caseat the Pulaski County Detention Center in Kentucky,an ICE representative recommended that a nurseremove information about suicide risks from aformer hunger striker’s health summary. In emailcorrespondence with staff at the Northwest DetentionCenter (NWDC) in Washington, the ICE WesternRegional Communications Director/Spokespersonasked for an update on the number of detainees whowere going to be placed on formal hunger strikesprotocols. The NWDC representative estimated12 people but asked the ICE spokesperson to holdoff while they confirmed the numbers. The ICEspokesperson replied, “OK but the wolves are atthe door. Maybe I can come up with something fuzzy using a round number.”Violations of Medical Ethics:The Role of ICE’s HealthProfessionals in AbusesAgainst Hunger StrikersThe documents reveal that ICE’s health professionalshelped facilitate and enable abuses against hungerstrikers, in contravention of their ethical obligationsand international human rights norms. They lenttheir names and credibility to medical declarationsin support of motions for force-feeding and otherinvoluntary medical procedures. In some cases, theyfailed to ensure that even the most basic standardsfor adequate medical monitoring were met.A New Opportunity: Ending aSystem of AbuseICE’s treatment of hunger strikers reflects thebroader context of harm and abuse endemicto the immigration detention system — whichhunger strikers themselves are protesting. As aformerly detained hunger striker, Luis Yboy Flores,noted, “You cannot compare being in immigration[detention]; it’s like something out of a horror story.”Hunger strikes continue in ICE detention as of thiswriting, as detained people at risk of contractingCOVID-19 make pleas for basic sanitation, safety, andthe ability to practice social distancing behind bars.7ICE officials and detention officers have respondedwith extreme measures, including use of pepperspray, physical force, rubber bullets, and facilitywide lockdowns, in addition to force-feeding andretaliatory punishment for those who are singled outas instigators.The documents reveal the architecture of abusethat underpins ICE’s response. They describe theroutinization of the coercion and retaliation againsthunger strikers that continue today. Rather thanaddress the underlying circumstances that led tothe hunger strike, ICE’s policy and practice is tointimidate detained people into ending their protests.Moreover, by applying the same hunger strike policiesto people experiencing mental health crises, ICE putsalready vulnerable people at greater risk.Notably, newly elected President Joseph R. Bidenwas vice president during much of the periodcovered by the documents analyzed in this report.His administration now has an opportunity toacknowledge the abusive system that prompts somany immigrants to engage in hunger strikes, toend ICE’s cruel response to their protests, to heedhunger strikers’ urgent calls for humane treatmentBehind Closed Doors9

and release, and to begin phasing out the use ofimmigration detention entirely.To the U.S. Congress: Conduct robust oversight of ICE’s treatment ofhunger strikers in detention.Key Recommendations Request that the DHS Office of Inspector General(OIG) and Office of Civil Rights and Civil LibertiesThis section provides key recommendations to(CRCL) investigate and issue recommendationsprotect the rights of hunger strikers in ICE detention,regarding the conditions documented in thisas described below. A more detailed version isreport.provided at the end of the report. Require that ICE publicly report data on hungerstrikes by people in ICE custody.To the U.S. Department of HomelandSecurity (DHS): Invest in community-based social services asalternatives to detention. Prohibit the use of funds appropriated to theDHS to be used to force-feed or forcibly hydratedetained people engaging in a hunger strikewho have been determined by an independentlicensed physician to be competent in the refusal oftreatment. End the use of solitary confinement in immigrationdetention. Dramatically reduce funding for immigrationdetention and enforcement. Issue a directive on the medical treatment ofhunger strikers, consistent with national andinternational ethical norms, to ensure appropriatestandards of care. Support and pass legislation that begins theprocess of phasing out mandatory detention andthe use of detention entirely in our immigrationsystem. Phase out the use of immigration detention. Guarantee people in detention continued andregular access to independent health professionals,To the U.S. Department of Justice:including licensed physicians and psychiatrists Refrain from pursuing orders for force-feeding andwith provisions to ensure their clinicalother involuntary medical procedures.independence from the detaining authorities.8 Prohibit use of force and punitive measuresagainst hunger strikers. Ensure greater transparency and accountabilityin the immigration detention system, includingcomprehensive facility inspections withsafeguards for the participation of detainedpeople, and meaningful consequences for failedinspections. Provide compensation for people who have beensubjected to involuntary treatment and/or otherforms of abuse while hunger striking.10ACLU and PHR Research Report Refrain from retaliation against detained hungerstrikers.To Offices of the Federal Public Defender: Provide representation to people in detention onhunger strike who face court proceedings.To State Medical Boards: Investigate for license suspension or revocationany medical or health professionals who authorizeor participate in involuntary medical procedureson mentally competent individuals.

To Medical and Health ProfessionalAssociations: Censure and expel any medical or healthprofessionals who authorize or participate ininvoluntary medical procedures on mentallycompetent individuals. Issue clear guidelines reinforcing that forcefeeding and other involuntary medical proceduresare unethical and inconsistent with professionalnorms. Lobby for stronger and comprehensive protectionsfor health professionals who refuse to engage inunethical conduct, or act as whistleblowers.To Individual Health Professionals: Advocate individually or through professionalorganizations against health professionals’involvement in force-feeding and other involuntaryprocedures. Advocate for ICE to comply with ethical standardswith respect to the treatment of detainees. Advocate for the censure of health professionalswho have participated in force-feeding and otherinvoluntary procedures.To the UN High Commissioner for HumanRights, UN Special Procedures, UN TreatyBodies, and the Inter-American Commissionon Human Rights: Request official visits and unimpeded access toICE detention facilities to monitor conditions andinvestigate ill-treatment of hunger strikers. Seek information from the U.S. governmentregarding the use of coercive measures againsthunger strikers in immigration detention. Condemn the use of physical or psychologicalcoercion against hunger strikers in ICE detention.Behind Closed Doors11

BackgroundHistory of Hunger Strikes inthe United StatesHunger striking is undertaken as a nonviolent form ofprotest when other ways of expressing demands havebeen ineffective or are unavailable.9 Detained peoplehave historically used hunger strikes to protest avariety of issues, including inhumane conditions,religious abuses, and indefinite detention withoutcharge or due process.10 A hunger striker may bewilling to die to reach a political goal, but the strike israrely an attempt to commit suicide.11In recent years, hunger strikes drew nationalattention in the United States when the U.S. militarybegan to force-feed detainees at Guantánamo Baydetention center who were hunger striking in 2002,a practice which continued through at least 2013in response to strikes by hundreds of detainees.12Many of the hunger strikers had been in detentionfor more than a decade, held in solitary confinement,and subjected to sensory and sleep deprivation, aswell as environmental manipulation.13 Domestic andglobal medical and human rights groups, includingthe World Medical Association, American MedicalAssociation, United Nations human rights experts,PHR, and the ACLU, condemned the force-feeding asunethical and a form of cruel, inhuman, or degradingtreatment or even torture.14Hunger strikes have also occurred throughout theUnited States prison system, including a mass hungerstrike staged by some 30,000 prisoners in Californiafrom July to September 2013 to protest the use ofsolitary confinement.15 Several states, includingConnecticut and New York, employ force-feedingagainst prisoners who engage in hunger strikes.16Recent Hunger Strikes in ICEDetention and ICE ResponseRestraint chair used in force-feeding procedures, Guantánamo Bay.Photo AP/Charles Dharapak12ACLU and PHR Research ReportThroughout the Obama and Trump administrations,hunger strikes have been commonplace in ICEdetention centers. In March 2014, some 750 peopledetained at ICE’s Northwest Detention Center inTacoma, Washington began a hunger strike to protestongoing deportations and inhumane conditions.17Hunger strikers reported being threatened withretaliation, including denial of commissary privilegesand force-feeding. ICE began placing hunger strikers

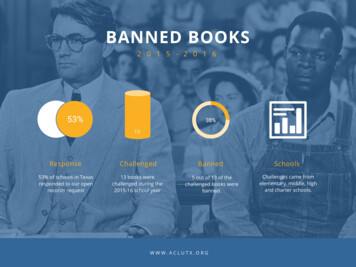

in solitary confinement until the ACLU obtained acourt order halting the practice.18The Tacoma hunger strikes was one of themany organized in recent years to protest cruelimmigration policies—and one of many which ICEmet with abuse and retaliation. From May 2015through early 2020, Freedom for Immigrantsdocumented hunger strikes by at least 1,600 peopleacross 20 ICE detention facilities.19 In 2019 alone,the International Consortium of InvestigativeJournalists identified 182 cases in which ICE placedhunger strikers in solitary confinement.20Hernandez-Diaz—have died in detention, raisingserious questions about medical neglect and abuseduring and after their hunger strikes ended.28Notably, all three men were detained at facilitiesowned and operated by private prison companies.In October 2019, following Hernandez-Diaz’s death,around 40 Cuban asylum seekers at the RichwoodCorrectional Center in Louisiana began a hungerstrike in protest and were reportedly beaten andhandcuffed.29Recent confirmed reports of ICE force-feeding camein January 2019,

Behind Closed Doors 7 tubes are inserted into a vein in the arm, leg, or neck via needles. The procedures can cause local pain and bleeding, can cause damage to blood vessels, and increase risk of infections and other complications. Forced urinary catheterization: a tube is inserted into the urethra (the orifice through