Transcription

Napoleon’s ShadowFacing Organizational DesignChallenges in the U.S. MilitaryBy J o h n F . P r i c e , J r .that impede flexibility, adaptability, andcreativity and undermine the executionof its operations in an increasingly challenging environment. In 2001, Major EricMellinger, USMC, wrote, “The modernmilitary staff embodies the industrial ageprecepts of hierarchical, vertical flows ofwork and supervision.”2 This critique echoedthe indictment leveled by General AnthonyZinni, USMC, the former commander ofU.S. Central Command. He stated, “Napoleon could reappear today and recognize myCentral Command staff organization: J-1,administrative stovepipe; J-2, intelligencestovepipe—you get the idea. The antiquatedorganization is at odds with what everyoneelse in the world is doing; flattening organization structure, decentralizing operations,and creating more direct communications.Our staff organization must be fixed.”3Despite this acknowledgment of theproblems generated by outdated structure,the military has continued to resist change inmost sectors. This resistance is grounded inthe daunting size of DOD, the natural inertiaof the organization, and its accustomed use ofthe “vertical flow of control, facilitating dissemination of orders from top to bottom andensuring compliance from bottom to top ina rapid efficient manner.”4 Since this emphasis is unlikely to change, the key to gettingleaders to adopt a new structure depends onshowing the adverse impacts of the currentstructure on organizational performanceand employee behavior and how both willimprove through structural change. As aU.S. Navy (Spike Call)In the world of competitive triathlons,there is a saying: “You might not winthe race in the swim, but you can certainly lose it there.” The maxim emphasizes how initial actions lay the foundationfor success or failure. For leaders, decisionson organizational structure are similar tothe triathlon swim; it may not be the key toorganizational success, but failure to recognize the importance of structure selectionand maintenance—and the impact it has onemployee performance—could easily be thesource of downfall.Next to choosing the organization’sstrategy, the selection of organizationalstructure is arguably the next most important decision leaders make. In DesigningOrganizations, Jay Galbraith points out,“By choosing who decides and by designingprocesses influencing how things are decided,the executive shapes every decision made inthe unit.”1 In today’s fast-paced, competitiveenvironment, organizations can ill affordto neglect the advantages that come fromorganizational design. Despite this reality,large traditional organizations such as theDepartment of Defense (DOD) continue tomaintain stifling, rigid bureaucracies thathamstring talent and place the organizationat a disadvantage.Defensive StructuresWhile still the premier fightingforce in the world, the U.S. military stubbornly retains organizational structuresColonel John F. Price, Jr., USAF, is Vice WingCommander for 375th Air Mobility Wing and recentlycompleted a tour on the Joint Staff.48 JFQ/ issue 68, 1 st quarter 2013 Army lieutenant colonel briefs commanding general Joint TaskForce–Haiti on internally displaced persons camps in Port-auPrince during Operation Unified Responsendupres s . ndu. edu

priceRAND study pointed out, “The challenge forthe U.S. military is to develop new organizational structures that achieve the efficienciesand creativity businesses have gained in thevirtual and reengineered environments,while at the same time retaining the elementsof the traditional, hierarchical, commandand control system (for example, discipline,morale, tradition) essential for operations inthe combat arena.”5Beyond the Org ChartTo appreciate the impact of structuraldecisions, we must comprehend the multiplecomponents of the structural dimension.According to recent research by JosephKrasman, a comprehensive look at structurerequires consideration of routinization, standardization, span of control, formalization,and centralization.6 Taken together, thesecomponents provide a significantly expandedconcept of organizational structure, and itbecomes easier to see how structure decisions have so much influence on employeebehavior.Leaders must also contend with thefact that organizational design is a continualprocess. As Galbraith points out, “Leadersmust learn to think of organize as a verb,an active verb. Organizing is a continuousmanagement task, like budgeting, schedulingor communicating.”7 Unfortunately, someorganizations, especially large ones, continueto view organizational structure as a onetime, foundational decision that they arereluctant to revisit because of the extensiverepercussions of organizational structurechanges. However, the dangers of failing toadapt are much more significant than theinconveniences of structural change, even ina large hierarchical bureaucracy.Impact of InactionWhile effective in the disseminationof top-down direction, the current militarystructure has numerous adverse impacts onthe military members currently serving. Atthe individual level, the military’s hierarchical bureaucratic structure undermines creativity, hinders empowerment and sense ofownership, and fosters cynicism. The sameorganization that rapidly responds aroundthe globe to the directions of senior officersprovides almost no voice to the hundreds ofthousands in the lower ranks. As a result,the organization’s adaptability and flexibility are significantly impaired becausen d u p res s .ndu.edu navigational choices are addressed only bythe most entrenched in the organization.Furthermore, the functional stovepipes thatcomprise the central columns of the organizational structure only serve to fractureteamwork, collaboration, and knowledgedistribution. It is no surprise that thenBrigadier General Zinni and others argued,“In a crisis, the dusty wire diagram sittingatop most of our desks does not spring intoaction as one amorphous mass.”8The current structure undermines theamazing talents of officer and enlisted Servicemembers by burying them under excesslayers of supervision and constructingbarriers to information exchange. Insteadof creating opportunities, the oppressivestructure stifles initiative and slowly drainstalent from the organization. As ArnoPenzia, Bell Laboratory’s chief scientist,states, “The problem with hierarchies is thatpeople at every level have the power to sayNapoleon’s shadow and improve organizational design. However, in most cases,the structural adjustments were temporaryfixtures stood up to address a specific contingency operation, acquisition program,or other “hot topic.” Interestingly, in manycases, these ad hoc organizations are crossfunctional or matrixed structures specificallydesigned to cut through the day-to-daybureaucracy. Somehow, we have realizedthese reliable structures are preferred forcrisis scenarios when speed, accuracy, andcreative thinking are at a premium, but whenthe crisis ends, we return to the sluggish,stovepiped hierarchy.One aspect that makes this more difficult is the challenge of transitioning theentire military structure. Instead of reforming one or even a set of organizationalcharts, adaptation for DOD would requirethe near simultaneous transition of thousands of organizational charts. The realitydespite the problems generated by outdated structure, themilitary has continued to resist change in most sectorsno.”9 The unfortunate reality in the militaryis that most of those people telling you “no”do not have the authority to tell you “yes,”but are still able to clog the arteries of theorganization.In a terrible irony, the effort by seniormilitary leaders to smooth decisionmakingand improve control only results in slowingdown the organization and stifling its abilityto react to opportunities and threats. Insteadof helping the organization, the structurefosters dependence and a greater need fordirection from senior leadership. As Martinvan Creveld states, “An organization witha high decision threshold—that is, one inwhich only senior officials are authorizedto make decisions of any importance—willrequire a larger and more continuous information flow than one in which the thresholdis low.”10 It is time for senior defense leaders torecognize the impediment that the organizational structure has become and consider theconsequences of failing to change in the faceof difficult economic pressures and myriadmilitary threats.Leaving Napoleon BehindOver the last decade, the military hasmade a few feeble attempts to step out ofof this obstacle was seen in the recent effortsof U.S. Southern Command to reform itsorganizational structure. In a progressiveattempt to depart from the Napoleonicstovepipes, Admiral James Stavridis createda matrixed organization focused on itsprimary mission areas. However, as soon asthe Haitian earthquake crisis hit and extensive coordination was required with externalagencies, the command reverted to thetraditional J-structure mid-crisis primarily because of the structural misalignmentwith other DOD organizations. While somewould use this example to derail futurerestructuring efforts, the real lesson lies inthe need for a coordinated overhaul of theentire system, and that overhaul needs tostart now.Radical steps are required by defenseleaders. In Leading the Revolution, GaryHamel points out that “Nonlinear innovation requires a company to escape the shackles of precedent and imagine entirely novelsolutions.”11 For DOD, the novel solution isan adaptive organizational structure thatflattens the hierarchy, empowers the membership, and fosters flexibility and creativity.This organizational design should consistof the following characteristics identified byissue 68, 1 st quarter 2013 / JFQ 49

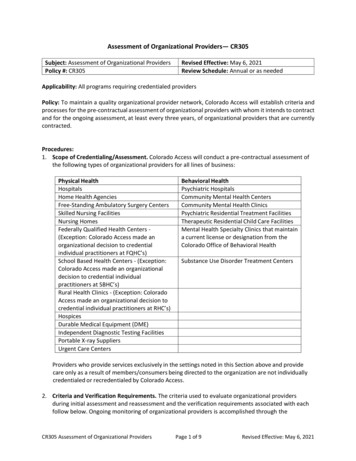

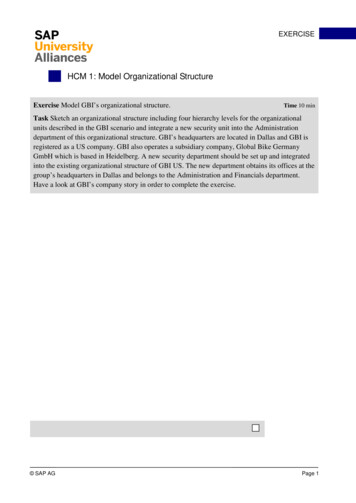

Special Feature Napoleon’s Shadow highspans of controluse of temporary structures powerful information systems constantly evolving structure.12 extensiveDecentralization removes the barriersto creativity and freedom of action, whilewide spans of control reduce the layers ofbureaucracy and keep senior officials more intouch with operations.13 Increasing the use oftemporary structures enables adaptation andflexibility and indirectly provides a forumfor structural experimentation within theorganization. Information systems enablenetworking and collaboration in virtualstructures and allow members to escapegeographical or functional barriers. Finally,the establishment of structure as a variableinstead of a fixed entity fosters a learningorganization culture, which is vital in today’senvironment.Act NowWhile some would have us wait forthe elusive “time of peace” to implementchange, now is the perfect time to executeneeded structural change in DOD. Budgetarycontractions and impending personnel drawdowns demand increased efficiency and placea great deal of stress on the existing structure.Congressional pressure to reduce the bloat ofthe general/flag officer corps creates opportunities to eliminate excess structural layers.It is time to stop renting extra office spacein Northern Virginia because the Pentagonstaffs long ago outgrew one of the world’slargest office buildings and start organizingfor 21st-century operations.While a comprehensive reform effortwill involve all of DOD, the proper startingpoint for the process must be with the JointStaff. As an extension of the Chairman, thisstaff serves as the interface with both theService staffs collocated in Washington andthe combatant command staffs distributedaround the world. The Joint Staff helps tofacilitate the interchange between the Services’ organize, train, and equip missions;the combatant command’s regional engagement operations; and the Office of theSecretary of Defense’s guidance and policy.Organizational change efforts at this criticaljuncture will cascade into the partnering50 JFQ/ issue 68, 1 st quarter 2013 the combatant commands occupy the execution role as they employ today’s force, whilethe Services are charged with the preparationrole of generating tomorrow’s force whilesustaining today’s. However, when we lookat each organization’s staff arrangement, wetypically see execution centered on the J3but also distributed across the staff, whilepreparation roles are scattered across thefunctional stovepipes.The temporal dividing line must be thedriving force in the staff reorganization effortinstead of attempting to organize aroundthe competing demands of geography andfunctional capabilities. The current systemdisperses parts of execution and preparationthroughout the organization and desynchronizes the efforts. Even worse, because thesystem has aspects of execution laced acrossthe organization, it results in every functionalarea gravitating to current operations, whichcauses the entire organization to dive to thetactical level. To avoid this reality, temporalseparation, instead of functional “cylinders ofexcellence,” must be the basis for staff design.This simple bifurcation would significantlycompress the staff structure to reflect priorityof effort—again, execution and preparation.It would also reduce the problems of duplication of effort and information fratricide byeliminating the artificial barriers formed bythe functional arrangement.The implementation of this constructwould result in the elimination of functionalhierarchies on the military staffs. InsteadDecentralized, Cross-functional Staff ConceptDirector of Staff Synchronization manages work flow andspans current-future transitionDirector of Staff Synchronization Operational Processes(Plans, Programs, Budgets, Posture, Risk/Readiness)Directors of Executionand Preparationintegrate allaspects ofcurrent and futureoperationsOperational Enablers(Intelligence, Logistics, C4ISR, Personnel, Legal, Medical)Operational Areas(Africa, Europe, Asia, Americas, Pacific, Space)Operational Domains / Capabilities P R E PA R AT I O N decentralizationorganizations and promote a DOD-wideshift driven by the natural tendency of military organizations to seek alignment.If we know it is time to restructure—and it appears the logical starting point isthe Joint Staff—the question remains: whatshould the new structure look like? By following Louis Sullivan’s maxim “form everfollows function,” we find our structuralanswer by looking at the core purpose ofour military enterprise.14 If we filter throughall of the creative language in the nationalstrategy documents and observe how theorganization is resourced, it is apparent thatDOD is focused on two desired outcomes:win the current fight (in whatever form thatmay be), and prevent/ prepare to win the nextconflict—in order to secure America’s globalposition. This description of the military’score purpose can be condensed down to twofoundational concepts that form the basisfor a new military structure: execution andpreparation.These two pillars are the majoroperating lanes on every staff and in everyfunctional area. They represent the temporal separation we see between operationalplanning and execution, between procuring capabilities and employing them, andbetween recruiting and training personneland deploying and employing personnel. Ifwe look at DOD on a grand scale, it becomesclear that this preparation/execution divide isthe primary separation between the Servicesand combatant commands. For the most part, EXECUTIONWilliam Fulmer in his Shaping the AdaptiveOrganization:(Land, Naval, Air, Space, Cyber, Nuclear, SOF)Cross-functional Teams(Crisis Action, Operational Planning, Working Groups, etc.)ndupres s . ndu. edu

U.S. Navy (Spike Call)priceArmy colonel briefs commander of UnitedNations Stabilization Mission in Haitiof having directorates focused on personnel, intelligence, logistics, and so forth, therevised staff would matrix each of thesefunctions into the core areas of executionand preparation depending on its role. Whilefunctional leadership would still exist, theoverall coordination of effort across the staffwould be greatly simplified. The combatantcommander or Chairman would be able tofocus attention on two primary channels:current operations and future operations.The dividing line between current and futureoperations in this construct would differsignificantly from present models. Whilesome fluctuation would be needed to balanceworkloads, the baseline for current operan d u p res s .ndu.edu tions would be the present out to 6 months,where future operations would take the lead.The word operations in this construct hasa greatly expanded meaning to include allaspects of military operations from budgetary planning and platform procurement tokinetic operations in a combat zone.This staff is not intended to operatein functional areas. Instead, it is designedto operate like a joint task force or a crossfunctional team that pulls together thedesired expertise to address specific issues asthey arise. Instead of continuing the currentprocess of creating ad hoc groups every timean issue arises, team members are alignedin cells capable of working independentlyor collectively in crisis. While this structuremay seem foreign on initial review, there arenumerous examples of it already residing inour staffs. The Pakistan-Afghanistan Coordination Cell is a perfect example of a highlyeffective cross-functional team that existedindependently on the staff before recentlybeing absorbed by the J5. Another examplecommon to many staffs is the commander’saction group. These multifunctional miniature think tanks, designed to tackle issues forsenior commanders, are perfect examples ofhow a standing, matrixed team concept couldbe employed. Senior functional area expertswould still be resident in the staff to assistwith developmental and assignment issues,but the elimination of the functional directorates would remove barriers to collaboration and improve staff integration.Transitioning the Joint Staff and combatant command staffs to this model wouldnot be easy because it would remove numerous layers of the hierarchy and deal a seriousblow to the functional stovepipes. However,the improvements in agility, collaboration,and end-to-end process management wouldbe significant. Shifting our major staffs tofocus on operational execution and preparation helps ensure unity of effort and continuity in plans, programs, and budgets.While significant detail would need tobe added to make this concept a reality, it isclear that this approach could provide severalkey benefits. First, it ensures the entire staffis focused on the core DOD mission and notdivided by functional allegiances. Secondly,it ensures the return of a strategically focusedstaff by devoting a large portion of the staffto focus on future strategic development.The intentional temporal separation wouldbe complemented by the consolidation ofthe staff, which would ensure sufficientconnections to current operations to enablecontinuity of thought in concepts, planning,and lessons learned. Third, the consolidationof the staff into a single current and futureoperations group would enable the elimination of numerous general/flag officer positions that were previously required to leadthe numerous directorates. Instead of servingas stovepipe chieftains, the remaining seniorofficers would be true generalists chargedwith facilitating the efforts of the crossfunctional teams. Fourth, the removal ofbureaucratic layers and duplication of effortcombined with improved coordination wouldprovide increased staff efficiency in the faceissue 68, 1 st quarter 2013 / JFQ 51

Special Feature Napoleon’s ShadowNEWfrom NDU Pressfor theCenter for Technology and NationalSecurity PolicyInstitute for National Strategic StudiesDefense Horizons 73Toward the Printed World: AdditiveManufacturing and Implications forNational SecurityBy Connor M. McNulty, Neyla Arnas,and Thomas A. CampbellAdditive manufacturing—commonlyreferred to as “three-dimensionalprinting”—is a fast-growing, prospectivegame-changer not only for nationalsecurity but also for the economy as awhole. This form of manufacturing—whereby products are fabricated throughthe layer-by-layer addition of materialguided by a precise geometrical computermodel—is becoming more cost-effectiveand widely available. This paper introducesnontechnical readers to the technology,its legal, economic, and healthcare issues,and its significant military applicationsin areas such as regenerative medicineand manufacturing of spare parts andspecialized components.Visit the NDU Press Web sitefor more information on publicationsat ndupress.ndu.edu52 JFQ/ issue 68, 1 st quarter 2013 of impending personnel cuts. Finally, andmost importantly, the “practice like you play”maxim would finally be realized in the headquarters staffs as the agility, creativity, andexpertise of the cross-functional teams seenduring crisis response become the normalmode of operations.Closing ThoughtsAs this article is being written, the mostsubstantial cuts in military spending in thelast several decades are being considered,and the recent Quadrennial Defense Reviewstated that one of its two goals was “to furtherreform the Department’s institutions andprocesses to better support the urgent needsof the warfighter.”15 The need for structuralreform combined with the fiscal demandfor efficiencies, taken together, shouldprovide sufficient motivation for leadershipto consider resuming their responsibilitieswith regard to organizational design andrevolutionize the antiquated structures inthe Services. If we are truly serious aboutimproving efficiency, saving taxpayer dollars,and taking care of our people, what could bebetter than doing all three by improving theorganizational structure?Think about the increased accessibilityto leadership, the increased span of control,and the decentralization that would occurfrom this action. While the concept presentedis only one of many options that could bepursued, it should be clear that there is greatvalue in pursuing design ideas that break themold of the past in order to make the organization more competitive and sustainablein the future. Do we have the courage to putstructure back in the leadership discussion, orare we doomed to follow Napoleon throughanother century? JFQ4Arthur Huber et al., The Virtual CombatAir Staff: The Promise of Information Technologies(Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 1996), 2.5Ibid., xiii.6Joseph Krasman, “Taking Feedback-Seekingto the Next ‘Level’: Organizational Structure andFeedback-Seeking Behavior,” Journal of Managerial Issues 23, no. 1 (April 2001), 10.7Galbraith, 154.8Anthony C. Zinni, Jack W. Ellertson, andRobert Allardice, “Scrapping the Napoleonic StaffModel,” Military Review 72, no. 7 (1992), 84.9William Fulmer, Shaping the Adaptive Organization (New York: AMACOM, 2000), 184.10Martin van Creveld, Command in War(Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985), 236.11Gary Hamel, Leading the Revolution(Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2000), 14.12Fulmer, 179.13Mellinger, 25.14Steven Bradley, “Does Form Follow Function?” Smashing Magazine, March 23, 2010, available at ow-function/ .15Quadrennial Defense Review Report (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, February2010), iii, available at .pdf .NotesJay Galbraith, Designing Organizations: AnExecutive Guide to Strategy, Structure, and Process(San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2002), 6.2Eric Mellinger, “Cutting the Stovepipes: AnImproved Staff Model for the Modern UnifiedCommander,” unpublished manuscript, April2001, 31, available at www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?Location U2&doc GetTRDoc.pdf&AD ADA401422 .3Anthony C. Zinni, “A Commander Reflects,”U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 126, no. 7 (2000),36.1ndupres s . ndu. edu

Napoleon’s Shadow Facing Organizational Design Challenges in the U.S. Military By John F. Price, Jr. Colonel John F. Price, Jr., USAF, is Vice Wing Commander for 375th Air Mobility Wing and recently completed a tour on the Joint Staff. that impede flexibility,