Transcription

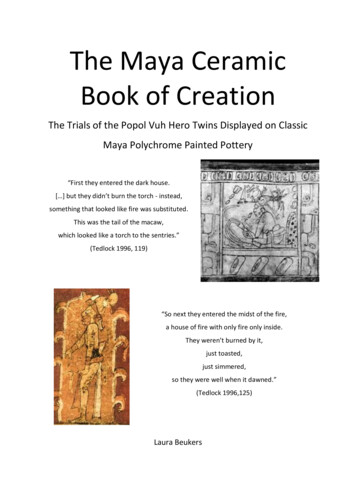

The Maya CeramicBook of CreationThe Trials of the Popol Vuh Hero Twins Displayed on ClassicMaya Polychrome Painted Pottery“First they entered the dark house.[ ] but they didn’t burn the torch - instead,something that looked like fire was substituted.This was the tail of the macaw,which looked like a torch to the sentries.”(Tedlock 1996, 119)“So next they entered the midst of the fire,a house of fire with only fire only inside.They weren’t burned by it,just toasted,just simmered,so they were well when it dawned.”(Tedlock 1996,125)Laura Beukers

Text: Tedlock, D., 1996. Popol Vuh: The Definitive Edition of the Mayan Book of the Dawn ofLife and the Glories of Gods and Kings. New York: Simon & Schuster.Figures: Kerr, J. Maya Vase Database: Kerr Number 1561, added 01-04-1998. Digital image,www.mayavase.com, accessed 2009-2013.Kerr, J. Maya Vase Database: Kerr Number 3831, added 25-01-1999. Digital image,www.mayavase.com, accessed 2009-2013.

The Maya CeramicBook of CreationThe Trials of the Popol Vuh Hero Twins Displayed on ClassicMaya Polychrome Painted PotteryAuthor: Laura BeukersCourse: Research Master Thesis – ARCH 1046WTYStudent number: 0417920Supervisor: Professor M.E.R.G.N. JansenSpecialisation: Religion and Society of Native American CulturesUniversity of Leiden, Faculty of ArchaeologyLeiden, 17 June 2013

Email: laura beukers@hotmail.comTelephone number: 31793518367 316174232

Table of ContentsPreface . 7Chapter 1: The ancient and contemporary Maya .111.1 The ancient Maya civilization . 11The Preclassic period (ca. 2000 B.C.-A.D. 250). 12The Classic period (ca. A.D. 250-900/1100) . 17The Terminal Classic (800-900/1100) . 20Postclassic (900/1100-1500) . 22Conquest (1502-1697) . 231.2 The rediscovery of the Maya civilization and decipherment of the script . 241.3 The contemporary Maya . 27Chapter 2: The “seeing instrument” of the Ancient Maya .302.1 The alphabetic Popol Vuh . 31History of the document . 32Originality of the Popol Vuh . 33Authors of the Popol Vuh . 352.2 The hieroglyphic Popol Vuh . 362.3 The oral Popol Vuh . 392.4 Conclusion . 40Chapter 3: Maya ceramics .423.1 Production and painting . 43Production process. 43Painting process . 44Workshops. 453.2 Hieroglyphic texts . 46The PSS . 473

3.3 Maya artists . 503.4 Functions . 53Service ware . 54Social currency . 56Funerary ware . 583.4 Conclusion . 59Chapter 4: Theory and Method of iconography .614.1 Iconographical theory. 61Panofsky’s iconography . 61Primary meaning . 634.2 Semiotcs . 644.3 Iconographical method. 674.4 Illustrating a story . 704.5 Concluding remarks . 73Chapter 5: The Hero Twins identified .755.1 The birth of heaven and earth . 75The creation of the cosmic in the Classic period . 76The creator gods. 795.2 The trials of Jun Junajpu and Wuqub Junajpu . 82Jun Junajpu and Wuqub Hunajpu . 83Head in tree . 84Ballgame scene . 855.3 The birth of Junajpu and Xbalanq’e . 88Junajpu and Xbalanq’e . 88The Hero Twins identified . 90Iconographical elements of the Hero Twins . 91Nominal glyphs . 934

Examples of representations of the Hero Twins . 935.4 Categorizing the Hero Twins scenes on Maya ceramics . 95Chapter 6: The Hero Twins on earth .986.1 The defeat of Wuqub Kaqix . 98Wuqub Kaqix . 98Shooting of Wuqub Kaqix . 996.2 The defeat of Sipakna and Kab’raqan. 107Sipakna . 108The caiman represented on ceramic vessels . 111Kab’raqan . 112The significance of Wuqub Kaqix and sons . 1136.3 The defeat of Jun Batz’ and Jun Chowen. 114Jun Batz’ and Jun Chowen . 115Monkey’s on ceramics . 116Monkey conclusions . 1176.4 The summoning of Junajpu and Xbalanq’e to Xibalba . 118Missing scenes . 1196.5 Concluding remarks . 119Chapter 7: The Hero Twins in the Underworld . 1217.1 Greeting the Lords of the Underworld . 121The Lords of the Underworld . 121Mosquito represented on ceramics . 1237.2 The Houses of the Underworld . 124The House of Darkness . 125The House of Bats. 128The Houses of Blades, Cold, Jaguar and Fire . 1297.3 Death and resurrection of the Hero Twins . 1305

The Hero Twins as catfishes . 1317.4 The defeat of the Lords of Death . 132The Hero Twins as performers . 133The humiliation of the Death Gods . 1347.5 Concluding remarks . 136Chapter 8: The Classical version of Jun Junajpu . 1378.1 The shaping of humans out of maize . 137Jun Junajpu identified . 137Defeat of the Underworld Lords by Jun Junajpu . 138Resurrection scene . 139The dressing of the Maize God. 1408.2 Concluding remarks . 142Chapter 9: Conclusions . 143Abstract. 147Bibliography . 149Figures . 155Appendix 1 . 162Appendix 2 . 168Appendix 3 . 1706

PrefaceMy thesis will be an iconographic study of Classic Maya ceramics. Pictorial polychrome pottery is theprimary source of Classic Maya painting that is left to us. The pottery discussed in this thesis is of aparticular kind. These wares were exclusively for the elite and were in itself a symbol of prestige. Inthe sixth century we find the appearance of unique painting styles, the establishment of eliteworkshops and works that were so exceptional that they could be linked to specific painters. Thepainters of these vessels were among the most highly educated people in Maya society. They wereeducated in Maya history, science, ideology and cosmology and they also learned how to read andwrite (Reents-Budet 1994, 4-6). The elite painted pottery is therefore a fine source to get moreinformation about Maya mythology.A large amount of Classic Maya vessels originate from the illegal activities of tomb robbers.They were therefore ignored for a long time, because Maya scholars did not want to encouragerobbery. Besides that, it was also thought that texts on pottery were meaningless and were thereforeleft unstudied. Michael D. Coe was the first to elaborately study the themes displayed on paintedvases and the accompanying hieroglyphic texts (Coe 1973, 1978, 1983). Coe discovered that many ofthe painted scenes depicted the Hero Twin’s trials in the Underworld and many other tales from thePopol Vuh (Popol Wuj in modern K’iche’), the sacred “Book of council” of the K’iche’ Maya.The Popol Vuh is the creation story of the Maya. The document was written down sometimebetween 1554 and 1558, by authors that stayed anonymous (Christensen 2007, 37). It is commonlybelieved that the story of the Popol Vuh was actually much older and might once have been writtenin codex form. The opening chapters of the Popol Vuh describe the separation of the sky and the seaand the creation of the earth. It also retells the attempts of the creator gods to form humans. Thiscreation narrative is interrupted by the story of the heroic deeds of the twins Junajpu andXb’alanq’e1. This second part tells how these Hero Twins defeated Wuqub’ Kaqix (“Seven Macaw”), alarge anthropomorphic bird deity that had to be vanquished for his false claim to be the sun and themoon (Tedlock 1996, 75-88). The Popol Vuh then tells the story of the father and uncle of the HeroTwins, who were sacrificed by the Lords of the Underworld. The Hero Twins also end up in theUnderworld were they are tested by the Underworld Lords in a series of trials. Incredible tricksters asthey are the Hero Twins survive all the trials and defeat the Underworld Lords, Jun Kame and Wuqub’Kame. The Hero Twins then ascend to the sky and become the sun and the moon (Tedlock 1996, 89142).1The original spelling of Junajpu is Hunahpu and of Xb’alanq’e is Xbalanque, but I will uphold the newspelling.7

In my thesis I will compare passages from to Popol Vuh to Classic Maya pictorial polychrome pottery.There are vessels that have already been identified as displaying scenes from the Popol Vuh. Butthere has not been a specific research concerning this matter. Specifically it will be a study abouthow the Hero Twins are displayed on ceramics. Features of the Hero Twins have been identified byother Mayanists, such as Michael D. Coe. It is my intention to do the same at first, describe theimportant features of the Hero Twins by which they can be identified. With the help of thesefeatures I will investigate how they are displayed on ceramics. By an intense study into the ways thatthe Hero Twins are displayed on Maya ceramics it will be possible to tell more about this importantMaya creation story. But even more interesting would be to find parts displayed on ceramics that arenot mentioned in the Popol Vuh itself. It is likely that this creation story has been orally transmittedfor a long time, thus it would not be surprising that there are parts from this creation story that arelost to us and my goal is to retrieve these parts from the images displayed on pottery.I believe that pottery can give us much more information about Maya society than it hasdone do far. The Maya were very adapt in portraying stories in a very condensed down from. Alsothe Maya world was full of signs that carried multiple symbolic meanings. Justin Kerr wrote in hisarticle A Fishy Story:“For many years I have been seeing what I believe are abstract Maya concepts, condensed down to aspecific image or group of images. On examining these images closely, we find that the Maya, as didmany other people, use parts of complex imagery that would express a concrete idea. These imagesmay be as small as one or two glyphs to express the primary standard sequence, or parts of otherimages that carry the message” (Kerr 2003).I agree with him that the Maya used complex imagery to express certain ideas and even stories in avery abbreviated form. By an intense study of Maya pictorial pottery I believe it is possible to retrievemuch more information about the signs and symbols displayed in the pottery scenes.The Maya Vase DatabaseThe main source for the Maya vases in this study is the Maya Vase Database, an archive of rolloutphotographs created by Justin Kerr. This database is accessible online through the sitewww.mayavase.com. Click on the Maya Vase Database link on this homepage and it will redirect youto the search page where specific vessels can be found by entering their unique Kerr Number.The first attempt by Justin Kerr to make a flat picture of the design on a Maya vase was done by apaste composition. Kerr photographed a vase in different sections, matched these together and8

pasted them down to create a ‘rolled-out’ vase. In 1973 Kerr made the photographs for Michael D.Coe’s The Maya Scribe and His World. For this work he made a couple of still photographs of a vaseand then had them drawn by an artist. This was a rather expensive method and it did not allow himto study the original artist’s own hand and style. He knew than that he had to find a way to make arollout photographs in one step and for that he needed a peripheral camera. When he could notacquire one, he made one himself. Simply explained he put a vase on a turntable in front of anadjusted camera. By turning the surface of the vase, in the same speed as the film is moving throughthe camera, it was possible to make a rollout photograph of the cylindrical object (Kerr 1978). JustinKerr has now photographed more than 1900 Maya vases and made them available onwww.mayavase.com.OrthographySince the very beginning of Maya studies the spelling of the Maya words in our modern alphabet hasbeen a problem. This has lead to numerous different spellings of Mayan words. A good example isthe spelling used for the word ‘lord’ or ‘king’ which appears at least in five different forms in Mayastudies: ahau, ahaw, ajau, ajaw, and ‘ajaw. During the 1980s an official alphabet was created by theAcademia de Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala (ALMG) to create order, coherency and uniformity.However, although many scholars have adopted this new alphabet in their studies, the actualapplication of it is still done in various different ways. In this thesis the new alphabet and neworthography will be followed for Maya words, except for place names which have been incorporatedinto English, those will remain to be written in the old fashion. The reason being that these namesare well established into the geographical vocabulary, such as maps and road signs. Anotherexception are b’s, which according to the new orthography should all be glottalized (chab’ ratherthan chab), but since the glottalization makes no difference to the meaning of the words with b, thiswill not be used in this thesis. Also, accents placed on Maya words will be omitted, because Mayawords are pronounced with the stress placed on the last syllable. Thus Spanish-derived accents areremoved, writing for example Tonina instead of Toniná. Personal names of Maya rulers, gods, deitiesand figures from the Popol Vuh will not be written in italics. Although these are Mayan words andmost often have an underlying meaning, they are used to refer to a specific being and thus aretreated as proper names.In this thesis long-standing epigraphic conventions will be used:1) Transliterating Maya words in boldface-Syllabic sign in lowercase bold-Logograms in UPPERCASE BOLD9

2) Transcribing Maya words in italics-Reconstructed sounds are represented in [square brackets]3) Translated Maya words in “quotes”The following example is to indicate how the above mentioned stages function:1) BALAM2) ba[h]lam3) “jaguar”10

Chapter 1: The ancient and contemporary MayaThe Maya were once a thriving civilization, with grand cities that supported thousands of people. Theancient Maya cities were built up out of impressive temples and pyramids for the gods, palaces forthe rulers and elites, and grand plazas for public performances. The cities were surrounded by simplecommoners houses made of loam and straw roofs. The religion and ideology of the ancient Mayawas significant and complex, with a rich amount of creation myths and maintained by theperformance of countless rituals. In the aftermath of the conquest men believed that this civilizationwas completely wiped out and their customs and rituals forever lost. But it has become more andmore apparent that the Maya still thrive today. Albeit in smaller numbers and their practices andreligion somewhat Westernized. There are ancient Maya rituals that have survived through time andthat are still being performed in Maya villages today.1.1 The ancient Maya civilizationIn many areas of Mesoamerica people were living in agricultural villages well by 2000 B.C. (Sharerand Traxler 2006, 157-160). Mesoamerica is a term used to refer to civilizations that establishedthemselves within a defined geographical area. These civilizations shared linguistic and culturalfeatures; such as, the construction of stepped pyramids, the use of a 260-day and 365-day calendar,pictographic and hieroglyphic writing systems, the use of rubber and bark paper, etc. (Kirchhoff1943).Figure 1.1: Map showing the culture area of Mesoamerica (Covarrubias 2007).11

Mesoamerica covers the area from approximately northern Mexico to Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador,Honduras, Nicaragua and northern Costa Rica (figure 1.1). Multiple civilizations flourished in thisarea, such as the Olmec, Zapotec, Mixtec, and the Maya. The specific area that the ancient Mayaoccupied included the modern countries of Guatemala, Belize, the western parts of Honduras and ElSalvador, and the Mexican states Campeche, Quintana Roo, Yucatan, and the eastern parts ofChiapas and Tabasco (figure 1.2). The environment of this area varies greatly, from rough, steepmountains to broad plain areas. Maya scholars often divide the area into three geographical zones,the Pacific coastal plain, the highlands and the lowlands (Sharer and Traxler 2006, 26-30). As can bededuced from the name, the Pacific Coastal Plain covers the stretch of land along the Pacific, fromthe Mexican state Chiapas, through southern Guatemala and into El Salvador. The area is excellentfor agriculture and thus it is here that we find the first permanent settlements. This is also the areawere we see the first signs of a flourishing Maya civilization (Sharer and Traxler 2006, 31-34). To thenorth of the coastal plain we find the highlands, a mountainous area. Although the valleys in thehighlands have fertile soils, they are often disturbed by volcanic eruptions and earthquakes (Sharerand Traxler 2006, 34-35). The lowlands comprises the largest of the three areas. The area extendsover northern Guatemala, Belize, and the Yucatan Peninsula. Almost all of the terrain lies below 800m in elevation and its most characterizing feature is the tropical forest. This tropical forest provides awide range of resources and houses many animals (Sharer and Traxler 2006, 41-44). Of these animalsthe jaguar was deemed very powerful by the Maya. The jaguar is one of the most portrayed animalsby the Maya and its pelt, tails and paws were considered as valuable materials. The pelt coveredthrones, was worn by rulers and hanged in elite buildings as curtains.The Pre-Columbian history of the Maya can be subdivided into three periods: the Preclassicperiod (ca. 2000 B.C.-A.D. 250), the Classic period (ca. A.D. 250-900/1100) and the Postclassic period(ca. A.D. 900/1100-1500), which can each be further divided into period such as Early, Middle, Lateand Terminal (Sharer and Traxler 2006, 155-156).The Preclassic period (ca. 2000 B.C.-A.D. 250)The Preclassic period is marked by the widespread appearance of agriculture. In Mesoamerica themost common domesticated plants are maize, chili, squash and beans. In this period we also find thefirst domesticated animals, being turkey and dog (Sharer and Traxler 2006, 160-163). Another markerof the Preclassic period is the appearance of pottery. Pottery is the result of the firing of clay. Potteryvessels are quite difficult to transport and the emergence of pottery is therefore an indicator forpermanent settlements. The earliest pottery in Mesoamerica has been found on the Pacific Coast ofChiapas, Guatemala and western El Salvador and constitutes the Barra phase (ca. 1850-1650 B.C.).12

Figure 1.2: Map of the Maya area (Coe and Kerr 1998, 28).13

The ceramics from the Barra phase are quite simple and seem to be derived from the older traditionof making containers out of gourds. The following Locona phase (ca. 1650-1500 B.C.) displays morecomplexity in the pottery and in the Ocos phase (ca. 1500-1200 B.C.) there appears more diversity(Sharer and Traxler 2006, 160-161).The earliest Maya pottery consists of basic forms most suitablefor its function; such as the large, neckless jars for water storage and perhaps food products, andsimple open flatbased bowls for serving food and drinks. These cooking and storage vessels wereunslipped. Some wares were decorated by either punctuations, appliqués, incising, fluting or painting(Sharer and Traxler 2006, 161). In the Middle Preclassic period (ca. 1000-500 B.C.) we find a variety ofdistinctive ceramic traditions in the lowlands, indicating that colonization was undertaken bydifferent populations, quite possible distinct ethnic and linguistic groups (Sharer and Traxler 2006,177). Later in the Middle Preclassic period these distinctive ceramic traditions disappear and arereplaced by a more uniform ceramic tradition, the Mamom (ca. 700-400 B.C.) (Sharer and Traxler2006, 202). New forms of decoration in the Middle Preclassic include polychrome painting (black,white, red, and yellow paints applied after firing), bichrome slipping, and the beginnings of firedresist decoration, also known as the Usulutan tradition (Sharer and Traxler 2006, 181).In the Gulf coast lowlands of Mexico a complex society called the Olmecs already establisheditself in the Middle Preclassic period. Two major Olmec sites were La Venta and San Lorenzo. TheOlmec displayed a specific style in monumental architecture, pottery, figures, jades, and otherobjects that can be found throughout Mesoamerica. For many years therefore men assumed that theOlmec were the source for all civilization in Mesoamerica and was called the “mot

Book of Creation The Trials of the Popol Vuh Hero Twins Displayed on Classic Maya Polychrome Painted Pottery First they entered the dark house. [ ] but they didnt burn the torch - instead, something that looked like fire was substituted. This was the tail of the macaw, which