Transcription

Martial Artsof the World

Martial Artsof the WorldAn EncyclopediaVolume One: A–QEdited by Thomas A. GreenSanta Barbara, California Denver, Colorado Oxford, England

Copyright 2001 by Thomas A. GreenAll rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in aretrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations ina review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication DataMartial arts of the world: an encyclopedia / [edited] by Thomas A. Green.p. cm.Includes bibliographical references and index.ISBN 1-57607-150-2 (hardcover: alk. paper); 1-57607-556-7 (ebook)1. Martial arts—Encyclopedias. I. Green, Thomas A., 1944–GV1101.M29 2001796.8'03—dc2106 05 04 03 02 01200100282310 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an e-book. Visit abc-clio.comfor details.ABC-CLIO, Inc.130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911This book is printed on acid-free paper I .Manufactured in the United States of America

ContentsEditorial Board, ixContributor List, xiIntroduction, xvA Note on Romanization, xixMartial Arts of the World:An EncyclopediaVolume 1: A–QDueling, 97Africa and African America, 1Aikidô, 12Animal and Imitative Systemsin Chinese Martial Arts, 16Archery, Japanese, 18Europe, 109External vs. Internal ChineseMartial Arts, 119Baguazhang (Pa Kua Ch’uan),23Boxing, Chinese, 26Boxing, Chinese Shaolin Styles, 32Boxing, European, 44Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, 52Budô, Bujutsu, and Bugei, 56Capoeira, 61China, 65Chivalry, 72Combatives: Military andPolice Martial Art Training, 83Folklore in the Martial Arts, 123Form/Xing/Kata/Pattern Practice,135Gladiators, 141Gunfighters, 149Hapkidô, 157Heralds, 162Iaidô, 169India, 173Japan, 179v

Japanese Martial Arts, ChineseInfluences on, 199Jeet Kune Do, 202Jûdô, 210Kajukenbo, 219Kalarippayattu, 225Karate, Japanese, 232Karate, Okinawan, 240Kendô, 249Kenpô, 255Ki/Qi, 260Knights, 263Kobudô, Okinawan, 286Korea, 291Korean Martial Arts, ChineseInfluences on, 299Koryû Bugei, Japanese, 301Krav Maga, 306Kung Fu/Gungfu/Gongfu, 313Masters of Defence, 317Medicine, Traditional Chinese, 327Meditation, 335Middle East, 338Mongolia, 344Muay Thai, 350Ninjutsu, 355Okinawa, 363Orders of Knighthood,Religious, 368Orders of Knighthood,Secular, 384Pacific Islands, 403Pankration, 410Performing Arts, 417Philippines, 422Political Conflict and theMartial Arts, 435vi ContentsVolume 2: R–ZRank, 445Religion and Spiritual Development:Ancient Mediterranean andMedieval West, 447Religion and Spiritual Development:China, 455Religion and Spiritual Development:India, 462Religion and Spiritual Development:Japan, 472Sambo, 507Samurai, 514Savate, 519Silat, 524Social Uses of the MartialArts, 532Southeast Asia, 538Stage Combat, 551Stickfighting, Non-Asian, 556Sword, Japanese, 564Swordsmanship, EuropeanMedieval, 570Swordsmanship, EuropeanRenaissance, 579Swordsmanship, Japanese, 588Swordsmanship, Korean/HankukHaedong Kumdô, 597T’aek’kyŏn, 603Taekwondo, 608Taijiquan (Tai Chi Ch’uan), 617Thaing, 629Thang-Ta, 637Training Area, 643Varma Ati, 647Vovinam/Viet Vo Dao, 651Warrior Monks, Japanese/Sôhei, 659Women in the Martial Arts, 664

Women in the Martial Arts: Britainand North America, 684Women in the Martial Arts:China, 689Women in the Martial Arts:Japan, 692Wrestling and Grappling: China, 705Wrestling and Grappling:Europe, 710Wrestling and Grappling: India, 719Wrestling and Grappling: Japan, 727Wrestling, Professional, 735Written Texts: China, 745Written Texts: India, 749Written Texts: Japan, 758Xingyiquan (Hsing ICh’uan), 775Yongchun/Wing Chun, 781Chronological History of the Martial Arts, 787Index, 839About the Author, 895Contents vii

Editorial BoardD’Arcy Jonathan Dacre BoultonAssociate Professor of History, University of Notre Dame; medieval nobility andfeudalism; The Knights in the Crown: The Monarchical Orders of Knighthoodin Late Medieval Europe, 1326–1520 (1987).John ClementsDirector, Historical Armed Combat Association; reconstruction of Europeanmartial traditions for use as martial art; Medieval Swordsmanship: IllustratedMethods and Techniques (1998), Renaissance Swordsmanship: The IllustratedUse of Rapiers and Cut-and-Thrust Swords (1997).Karl FridayProfessor of History, University of Georgia; early Japan, Japanese military institutions and traditions; Hired Swords: The Rise of Private Warrior Power inEarly Japan (1992), with Professor Seki Humitake Legacies of the Sword: TheKashima-Shinryû and Samurai Martial Culture (1997); current book projectSamurai, Warfare and the State in Early Medieval Japan (Routledge, the Warfarein History series).Ronald A. HarrisRonald Harris and Associates; martial arts instructor in classic Filipino martialarts, Muay Thai, Boxe Francaise Savate, Taekwondo; numerous articles in BlackBelt, Inside Kung Fu, and similar popular publications.Stanley E. HenningAssistant Professor, Asia Pacific Center for Security Studies, Honolulu; Chineselanguage and martial arts, Asian military history; numerous articles in scholarlyjournals.Keith OtterbeinProfessor of Anthropology, State University of New York at Buffalo; crosscultural analysis of warfare, dueling, feuding; The Evolution of War (1970),ix

Comparative Cultural Analysis (1972), Feuding and Warfare (1991), and TheUltimate Coercive Sanction: A Cross-Cultural Study of Capital Punishment(1986).Joseph R. SvinthEditor, Electronic Journals of Martial Arts and Sciences; martial arts history, cultural studies; Kronos: A Chronological History of the Martial Arts and Combative Sports, numerous articles in scholarly journals.Phillip ZarrilliProfessor of Drama, University of Exeter, U.K.; India, performing arts, SouthAsian studies, folklore; When the Body Becomes All Eyes: Paradigms, Discourses, and Practices of Power in Kalarippayattu, a South Indian Martial Art(1998), Kathakali Dance-Drama: Where Gods and Demons Come to Play(2000); coauthor, Indian Theatre: Traditions of Performance (1990), WilhelmTell in America’s Little Switzerland (1987), The Kathakali Complex: Actor, Performance, Structure (1984); editor, Acting (Re)considered: Theories and Practices (1995), Asian Martial Arts in Actor Training (1993).x Editorial Board

Contributor ListBill AdamsDirector, Bill Adams Fitnessand Martial Arts CenterBuffalo, New YorkMikael AdolphsonHarvard UniversityCambridge, MassachusettsD’Arcy Jonathan Dacre BoultonUniversity of Notre DameNotre Dame, IndianaDakin R. BurdickIndiana UniversityBloomington, IndianaJoseph S. AlterUniversity of PittsburghPittsburgh, PennsylvaniaJohn ClementsDirector, Historical Armed CombatAssociationHouston, TexasEllis AmdurEdgeworkSeattle, WashingtonPhil DunlapAdvanced Fighting SystemsMahwah, New JerseyJeff ArcherIndependent ScholarLa Mesa, CaliforniaDavid BachrachUniversity of Notre DameNotre Dame, IndianaC. Jerome BarberErie Community College/SouthOrchard Park, New YorkWilliam M. BodifordUniversity of CaliforniaLos Angeles, CaliforniaAaron FieldsIndependent ScholarSeattle, WashingtonKarl FridayUniversity of GeorgiaAthens, GeorgiaTommy GongBruce Lee Educational FoundationClovis, CaliforniaLoren GoodmanState University of New Yorkat BuffaloBuffalo, New Yorkxi

Ronald A. HarrisDirector of Research, Evaluationand Information TechnologyLouisiana Office for AddictiveDisordersBaton Rouge, LouisianaStanley E. HenningAsia-Pacific Center for SecurityStudiesHonolulu, HawaiiRonald HoltWeber State UniversityOgden, UtahG. Cameron Hurst IIIUniversity of PennsylvaniaPhiladelphia, PennsylvaniaWilliam J. LongUniversity of South CarolinaColumbia, South CarolinaCarl L. McClaffertyUnited States RenmeiSekiguichi Ryû Batto JutsuDel Rio, TexasKevin P. MenardUniversity of North TexasDenton, TexasRichard M. MooneyDragon Society International Tai ChiKung Fu ClubWichita Falls, TexasGlenn J. MorrisMcNeese State UniversityLake Charles, Louisianaxii Contributor ListRon MotternIndependent ScholarElgin, TexasKeith F. OtterbeinState University of New Yorkat BuffaloBuffalo, New YorkMichael PedersonSt. John’s CollegeSanta Fe, New MexicoSohini RayHarvard UniversityCambridge, MassachusettsRoy RonUniversity of HawaiiHonolulu, HawaiiHistoriographical InstituteUniversity of TokyoTokyo, JapanAnthony SchmiegIndependent ScholarLexington, VirginiaBruce SimsMidwest HapkidôChicago, IllinoisJohn StarrState University of New York,Medical SchoolBuffalo, New YorkGene TauskIndependent ScholarHouston, Texas

Kimberley TaylorUniversity of GuelphGuelph, Ontario, CanadaTad TulejaHarvard UniversityCambridge, MassachusettsMichael TranMount Sinai Hospital of QueensNew York, New YorkChi-hsiu D. WengUnited States Shuai Chiao AssociationCupertino, CaliforniaNoah TulejaIndependent ScholarKensington, CaliforniaPhillip ZarrilliUniversity of ExeterExeter, EnglandT. V. TulejaSaint Peter’s CollegeSaint Peter’s College, New JerseyContributor List xiii

IntroductionAs many gallons of ink have been spilled in trying to define “martial arts” ashave gallons of blood in the genuine practice of martial activities. In this place Iwill not spill more ink. On the other hand, I do not contend that the efforts ofthose who try to develop such definitions waste their time. My only contentionis that these definitions are inevitably focused by time, place, philosophy, politics, worldview, popular culture, and other cross-cultural variables. So focused,they are destined to be less than universal. The same is true, however, of any attempt to categorize phenomena that, while universally human, are inevitably tiedto worldview, to mindset, and to historical experience.Many of the attempts to determine the boundaries of the martial arts drawon the model of the Japanese “cognate arts” by distinguishing between bujutsu(from bu, “warrior,” and jutsu, also romanized as jitsu, “technique” or “skill”)and budô (from “warrior” and dô, “way”). Those forms that are considered bujutsus are conceived to be combative ancestors of those that are considered partof budô, and the latter are characterized as disciplines derived from the earliercombat forms in order to be used as means of self-enhancement, physically, mentally, and spiritually. Bugei (“martial methods,” used to refer collectively to thecombat skills), itself, is commonly compartmentalized into various jutsu, yielding,for example, kenjutsu (technique or art of the sword), just as each way has its ownname, in this case, kendô (way of the sword).Such compartmentalization was a product of Japanese historical experiencein the wake of Pax Tokugawa (the enforced peace of the Tokugawa shogunate—A.D. 1600–1868), and it gained widespread acceptance with the modernization ofJapan in the late nineteenth century. Even in the twenty-first century, however, suchsegregation is not universal, as demonstrated by the incorporation of various martial skills (striking, grappling, and an arsenal of weapons) in the traditional ryûha(schools or systems) of contemporary Japan (see Friday 1997).Outside the contemporary Western popular context and the influence of theJapanese model, it is clear that a vast number of the world’s martial systems donot compartmentalize themselves as armed as distinct from unarmed, as throwing and grappling styles rather than striking arts. Grappling and wrestling “atxv

the sword” in European tradition; the use of knives, trips, and tackles in the“weaponless kicking art” of capoeira; the spears and swords (and kicks) of Chinese “boxing” (wushu); and the no–holds (or weapons)– barred nature ofBurmese thaing compel a reformulation of the distinctions among martial artsthat have informed our popular conceptions of them.In this context, even the notion of “art” is problematic. First, the term maybe used simply as a means of noting excellence, as a reference to quality ratherthan attributes. A more serious issue, however, arises from the fact that, in Western European culture, we commonly draw distinctions between art and life, theaesthetic and the utilitarian, work and sport, and art and science. These Eurocentric distinctions break down in the face of Thai ram dab, Indonesian pentjaksilat, and Brazilian capoeira, which are at once dance and martial exercise, andhave been categorized as both, depending on the interests of commentators who,with a few notable exceptions, have been outsiders to the traditions.In addition, attempts to comprehend the nature of “martial art” have beenfurther obscured by distinctions between self-defense/combat and sport (itself aculture-bound concept). George Godia characterizes the lack of fit between thecontemporary category of sport and the physical culture of traditional societieswell. “To kill a lion with a spear needs a different technique and different training than to throw a standardized javelin as far as possible. Spearing a lion was aduty to the young moran [Masai warrior], and different from a throw for leisure,enjoyment or an abstract result in terms of meters, a championship, or a certificate” (1989, 268). Perhaps for the same reasons, both our mechanisms for converting combatives (i.e., combat systems) to sports and for categorizing themcross-culturally frequently have fallen short of the mark.The present volume does maintain some working parameters, however.Martial arts are considered to be systems that blend the physical components ofcombat with strategy, philosophy, tradition, or other features that distinguishthem from pure physical reaction (in other words, a technique, armed or unarmed, employed randomly or idiosyncratically would not be considered a martial art). While some martial arts have spawned sports, and some of these sportsare considered in this volume, the martial cores of such activities rather than thesports per se are emphasized. Also, entries focus on those martial systems thatexist outside contemporary military technology. Thus, topics include Japanesesamurai (despite their part in the Japanese armies in earlier centuries), Americanfrontier gunslingers, and nineteenth-century European duelists (despite their useof firearms), as well as the sociocultural influences that have led to changingfashions in modern military hand-to-hand combat.Moreover, this volume is not instructional. Rather, it strives to present clear,concise descriptions of martial topics based on sound research principles. In aneffort to ensure this, the overwhelming majority of authors are both academicsand active martial practitioners.xvi Introduction

Obviously, a single work cannot hope to cover such a wide-ranging fieldas the martial arts of the world comprehensively. Although every attempt hasbeen made to include major topics from a broad spectrum of traditions—insofar as material exists to document such traditions and qualified authors couldbe found to clarify them—any overview cannot be exhaustive within this format. The richness and diversity of the world’s martial traditions make it inevitable that there is much that has been summarized or omitted entirely. Theentries, however, do provide an introduction to the growing scholarship in thesubject, and, to facilitate the pursuit of more specialized topics, each entry concludes with a bibliography of relevant works. Readers are urged to explore theirrelevant interests by means of these references. Martial Arts of the World attempts to range as widely as possible in its regional coverage and its subjectmatter. In general, longer, more comprehensive essay formats for entries (e.g.,“India,” “Religion and Spiritual Development: Japan”) have been favored overshorter entries (e.g., “Zen Buddhism”).I am indebted to Texas A&M University for a Faculty Development Leavefrom the College of Liberal Arts in 1999–2000 that allowed me to devote extra time to the project at a crucial stage in its development. Courtney Livingston provided invaluable research on the historical backgrounds of a number of Asian traditions. My colleague Bruce Dickson lent his considerableknowledge of anthropological theory and African cultures on more than oneoccasion. The nonmartial Roger D. Abrahams, Dan Ben-Amos, and BruceJackson all provided significant research leads during the formative stages ofthis project—as they have on so many other occasions. Many martial artistswhose names do not appear in the list of authors made valuable contributionsof time, information, introductions, e-mail addresses, and encouragement:David Chan, Vincent Giordano, Hwong Chen Mou, Leung Yee Lap, NguyenVan Ahn, Peng Kuang Yao, Guy Power, Mark Wong, and especially JerryMcGlade. I am grateful for the labors of Karl Friday, Gregory Smits, and Jessica Anderson Turner in creating consistency in the romanization of Japanese,Okinawan, and Chinese languages respectively. Their attention to linguisticand cultural detail went far beyond reasonable expectations. Todd Hallmanand Gary Kuris at ABC-CLIO took the process—from beginning to end—seriously, but in stride.My family maintained inconceivable tolerance for my behavior and clutterwhen I was in the throes of research. Alexandra was born into the family withonly minor turmoil. Colin provided computer expertise, library assistance, andcamaraderie during field research. My wife, Valerie, as always served as advisor,translator, and second opinion while keeping us all intact.My deepest gratitude goes out to you all.Thomas A. GreenIntroduction xvii

ReferencesFriday, Karl, with Seki Humitake. 1997. Legacies of the Sword: The KashimaShinryu and Samurai Martial Culture. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.Godia, George. 1989. “Sport in Kenya.” In Sport in Asia and Africa: A Comparative Handbook. Edited by Eric A. Wagner. New York: Greenwood, 267–281.xviii Introduction

A Note on RomanizationIn 1979, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) decided to employ the pinyin system of romanization for foreign publications. The pinyin system is now recognized internationally. As a result, the pinyin system is the preferred method in thepresent volume. Prior to this decision by the PRC, the Wade-Giles system hadgained wide international acceptance. Certain terms, therefore, may appear under spellings unfamiliar to the reader. For example, Wade-Giles Hsing I Ch’uanor Hsing I Chuan appears as pinyin Xingyiquan, and Wing Chun is romanizedas Yongchun. Pinyin spellings will be used in most cases. Old spellings, often unsystematic, are given in parentheses, for example Li Cunyi (Li Tsun-I). For thoseterms that are well established in another spelling, pinyin is noted in parenthesesfor consistency; for example, Pangai Noon (pinyin banyingruan). For Chinesenames and terms that are not associated with the PRC, we have chosen to follow locally preferred romanizations.xix

AAfrica and African AmericaAlthough many of the societies of Africa developed in close proximity toEgyptian civilization, with its highly developed fighting arts and rivalrywith other “superpowers” such as the Hittites, their martial systems developed in relative isolation from Middle Eastern combat disciplines. Rather,the martial arts, particularly those of the sub-Saharan Africans, belong toa world where (until the arrival of Europeans) the greatest martial threatscame from the other sub-Saharan groups, rather than from another continent. Some of the African peoples did have contact with the Arabs, whobrought Islam to the region and threatened the indigenous populationswith enslavement. To the best of current knowledge, however, the technology and martial development of cultures relying on the same subsistencebases (for example, hunting and gathering and agriculture) were roughlythe same for most of the civilizations of Africa, and they continued to beso until the arrival of the Europeans in the beginning of the fifteenth century. Even at this point, some groups resisted advanced weaponry when itbecame available because of cultural biases. For example, the Masai andKikuyu viewed firearms as the weapons of cowards.When one discusses the traditional African martial arts, it is important to note the wide variety and diversity of weapons that were available.Some groups had mastered the art of iron smithing. Although this knowledge probably crossed the Sahara in the fourth to fifth centuries B.C., thespread of iron occurred much later, and, in fact, the distribution patternswere irregular. For example, when the Portuguese entered southern Africaca. 1500, the Khoisan pastoralists (“Hottentots”) and hunter-gatherers(“Bushmen”) did not have access to iron.Those groups who did obtain iron were able to develop the usual variety of weapons that came from the art of iron smithing, such as swords,daggers, and metal spear points. For example, in Benin, Portuguese merchants encountered soldiers armed with iron swords and iron-tippedspears. Their shields, however, were wooden, and their anteater skin armor1

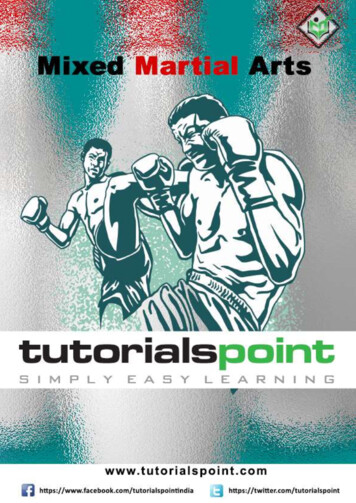

A picture of a Zuluwarrior holding alarge shield and ashort spear (assagai)characteristic of theirarmed combatsystem. Thisillustration appearedin a British publication during the warbetween Britishsettlers and the nativepopulation in Africa,1851. (Corbis)was of greater significance as magicalthan as practical protection. In fact,magical powers were attributed to mostWest African weapons and defenses.Even without metallurgy, other groupsproduced lethal clubs, staves, and spearswith stone points. African societies,some of them small states with standingarmies, were militarily formidable evenwithout the trappings of their Europeanand Middle Eastern contemporaries.Among the armed combat systemsthat developed were the ones that wereused by the Zulu peoples of SouthAfrica. The Zulu were proficient incombat with club, spear, and shield. Because they lacked body armor, the shieldbecame the protective device used by theZulu warriors. They initiated combat byeither throwing a spear at the opponentor using it for a charge. When spearcombat became impractical because ofthe range, the club was used for closequarters combat. The club-and-shield combination could be used in wayssimilar to the sword-and-shield combination of warriors in Europe.This type of fighting gave the Zulu an advantage in combat, as theyhad all of their ranges covered. The spear could either be used as a pole-armweapon that allowed the warrior to fight from a distance or as a shortrange stabbing weapon. In fact, Shaka Zulu revolutionized indigenous warfare by the use of massed formations and of the assagai (a stabbing spearwith a shortened shaft) in conjunction with a redesigned shield. Modern useof the spear in traditional Zulu ceremonies has demonstrated that they continue to be able to use the spear in conjunction with the shield effectively. Ifthe spear was lost, then clubs were used for effective close-range combat.Perhaps no weapon signifies African martial arts more than thethrowing iron. These instruments had many names from the different peoples that used them. They have been known as mongwanga and hungamunga. Many cultures have developed throwing weapons, from sticks tothe famous shuriken of the Japanese Ninja. Similarly, many African societies placed a premium on these types of weapons. The throwing irons weremultibladed instruments that, when thrown, would land with one of theblade points impaling its target. These weapons were reported effective at2 Africa and African America

a range of up to 80 meters. The wounds inflicted at such a long range werenot likely to be deadly. At distances of 20 to 30 meters the weapons couldconnect with lethal impact.In addition, these bladed weapons were also effective for hand-to-handcombat. Most of them had a handle, and so the blade projections also servedas parrying devices if needed. The iron from which the instruments were created was durable enough to stand the rigors of combat, even when one wasstruck against another throwing iron. Thus, the African warriors whowielded these weapons had not only a reliable projectile device that could beused for long-range combat, but also a handheld weapon for closing with theenemy. Therefore, it was not uncommon for a warrior to carry three or fourof these implements, always being certain to keep one in reserve.These throwing implements were also able to serve as the backboneof a system of armed combat. Given the absence of advanced forms of armor, African warriors were able to use these throwing irons to maximumeffect. Once a practitioner was able to penetrate the shield defenses of anopponent, a lethal or incapacitating wound was likely to occur, unless therecipient was able to avoid the strike. The effectiveness of these weaponsagainst an armored opponent is unknown.Another unique weapon is found among the Nilotic peoples of thesouthern Sahara region. These groups fought with wrist bracelets that incorporated a sharpened edge. Known by some groups as bagussa (Shangun;things that cause fear), the bracelets were said to be used for defenseagainst slavers. They were also used in ceremonial wrestling matches associated with agricultural festivals. These distinctive weapons continue to beutilized by the East African Nilotic groups of Kenya, Somalia, andEthiopia. For example, contemporary Turkana women of Nigeria still utilize the bracelets in self-defense. The weapons are brought into play byholding the arms in a horizontal guard position in front of the body untilthe opportunity arises to attack in a sweeping arc across the same plane using the razor-sharp bracelets to slash an opponent.Combat training was as essential to African martial arts as practice isfor martial arts of other cultures. One of the more interesting features ofAfrican combat systems was the reliance in many systems on the rehearsalof combat movements through dances. Prearranged combat sequences arewell known in various martial arts around the world, the most famous examples being the kata of Japanese and Okinawan karate. Such sequenceswere also practiced in ancient Greece, through the Pyrrhic war dances. TheAfrican systems used drums and stringed instruments to create a rhythmicbeat for fighting. Warriors, either individually or in groups, practiced usingweapons, both for attacking and defensive movements, in conjunction withthe rhythm from the percussion instruments. The armies of the AngolanAfrica and African America3

queen Nzinga Mbande, for example, trained in their combat techniquesthrough dance accompanied by traditional percussion instruments.From the evidence that survives, which, unfortunately, is scarce, manyscholars now believe that this type of training was central to the development of African martial arts systems. The enforcement of learning martialarts through the rhythm created by percussion instruments developed aninnate sense of timing and effective movement for the practitioner. In addition, these movements developed effective footwork for the warriors. Although these training patterns have been dismissed as “war dances,” expressive movement rather than martial drills, they actually played a centralrole in the training of African warriors. In a nonliterate culture, this typeof direct transmission through music allowed for consistent and uniformtraining without the need for written communication. This type of trainingis replicated today in the most popular of the African/African Americanmartial arts, capoeira (see below).Among the weapons that were used extensively by the Africans, oneof the most important was the stick. Stickfighting, which is practiced inmany cultures the world over, has especially been practiced in sub-SaharanAfrica. A variety of sticks continue to be used. For example, in addition toa knife and a spear, contemporary Nilotic men carry two sticks: a rungu(Swahili; a potentially deadly knobbed club) and a four-foot stick that isused for, among other things, fighting kin without causing serious injury.Stickfighting has existed in Africa as both a fighting sport and a martial art. In the sporting variant, competitors met for matches, and a matchconcluded when a certain number of blows were registered against one ofthe combatants. The number ranged from one to three, and the matchwould be halted to avoid serious injury. Blows against vital points of thebody or against the head were forbidden in most cases. For the Zulu, aswell as the Mpondo, who staged intergroup as well as intravillage stickfights, matches with neighboring polities often took on a deadly earnestquality. The head is reported to have been the preferred target.Thus, this type of martial arts activity fulfilled two functions for theAfrican practitioners. First, this practice allowed participants to directlyexperience combat at a realistic level with weapons. Although the target areas were limited, the possibility of injury was very real. Participants had tohave a high level of skill just to survive such a bout without injury. For thisreason, this type of stickfighting was an excellent preparation for directmilitary combat.In addition, stickfighting provided a sporting (although “sport” doesnot translate well in many non-Western contexts) outlet for the competitorsand the societies involved. The contests were a test not only of the competitors’ ability, but also of the training mechanisms that were imparted to4 Africa and African America

the competitors. In this respect, these matches were a point of pride for thevillages themselves. The warriors were representatives of the village or society, and when intersociety or intervillage competitions were held, eachcompetitor fought for the society’s as well as for his own honor. This typeof nonlethal outlet for warrior instincts allowed for a cathartic release ofenergy that helped to avoid all-out warfare.Stickfighting also gave warriors a foundation for armed combat.Learning how to strike, block, thrust, and move with the weapon is critical for any aspect of armed combat. Learning how to perform these basicmoves with a sti

Comparative Cultural Analysis(1972), Feuding and Warfare(1991), and The Ultimate Coercive Sanction: A Cross-Cultural Study of Capital Punishment (1986). Joseph R. Svinth Editor, Electronic Journals of Martial Arts and Sciences; martial arts history, cul- tural studies; Kronos: A Chronological History of the Martial Art