Transcription

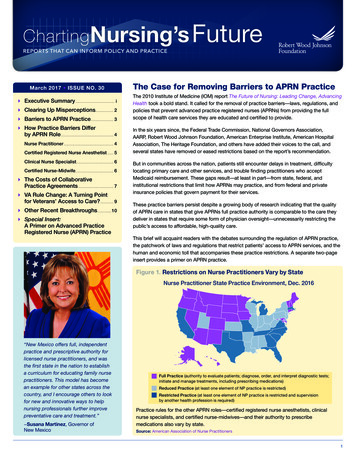

Charting Nursing’s FutureREPORTS THAT CAN INFORM POLICY AND PRACTICEMarch 2017 ISSUE NO. 30 Executive Summary. i Clearing Up Misperceptions. 2 Barriers to APRN Practice. 3 How Practice Barriers Differby APRN Role. 4Nurse Practitioner. 4Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist. . . 5Clinical Nurse Specialist. . 6Certified Nurse-Midwife. . 6 The Costs of CollaborativePractice Agreements. 7 VA Rule Change: A Turning Pointfor Veterans’ Access to Care?. 9 Other Recent Breakthroughs. 10 Special Insert:A Primer on Advanced PracticeRegistered Nurse (APRN) PracticeThe Case for Removing Barriers to APRN PracticeThe 2010 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, AdvancingHealth took a bold stand. It called for the removal of practice barriers—laws, regulations, andpolicies that prevent advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) from providing the fullscope of health care services they are educated and certified to provide.In the six years since, the Federal Trade Commission, National Governors Association,AARP, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, American Enterprise Institute, American HospitalAssociation, The Heritage Foundation, and others have added their voices to the call, andseveral states have removed or eased restrictions based on the report’s recommendation.But in communities across the nation, patients still encounter delays in treatment, difficultylocating primary care and other services, and trouble finding practitioners who acceptMedicaid reimbursement. These gaps result—at least in part—from state, federal, andinstitutional restrictions that limit how APRNs may practice, and from federal and privateinsurance policies that govern payment for their services.These practice barriers persist despite a growing body of research indicating that the qualityof APRN care in states that give APRNs full practice authority is comparable to the care theydeliver in states that require some form of physician oversight—unnecessarily restricting thepublic’s access to affordable, high-quality care.This brief will acquaint readers with the debates surrounding the regulation of APRN practice,the patchwork of laws and regulations that restrict patients’ access to APRN services, and thehuman and economic toll that accompanies these practice restrictions. A separate two-pageinsert provides a primer on APRN practice.Figure 1. Restrictions on Nurse Practitioners Vary by StateNurse Practitioner State Practice Environment, Dec. 2016“New Mexico offers full, independentpractice and prescriptive authority forlicensed nurse practitioners, and wasthe first state in the nation to establisha curriculum for educating family nursepractitioners. This model has becomean example for other states across thecountry, and I encourage others to lookfor new and innovative ways to helpnursing professionals further improvepreventative care and treatment.” Susana Martinez, Governor ofNew MexicoFull Practice (authority to evaluate patients; diagnose, order, and interpret diagnostic tests;initiate and manage treatments, including prescribing medications)Reduced Practice (at least one element of NP practice is restricted)Restricted Practice (at least one element of NP practice is restricted and supervisionby another health profession is required)Practice rules for the other APRN roles—certified registered nurse anesthetists, clinicalnurse specialists, and certified nurse-midwives—and their authority to prescribemedications also vary by state.Source: American Association of Nurse Practitioners1

CHARTING NURSING’S FUTUREThe Case for Removing Barriers to APRN PracticeExecutive SummaryIntroductionIn 2010 the Institute of Medicine issued a report, The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health, thatcalled for the removal of laws, regulations, and policies that prevent advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs)from providing the full scope of health care services they are educated, trained, and, in most cases, professionallycertified to provide. Since then, several states have lifted restrictions on APRN practice, but work remains to be done.Despite research showing comparable quality of patient care in states where APRNs have full practice authority, (thatis, the ability to practice to the full extent of their education, training, and certification), barriers to practice persist inmany places, and patients continue to experience gaps in care caused at least in part by those limits.Clearing Up Misperceptions (see p. 2)Much of the public is uninformed or misinformed aboutwhat APRNs do. This lack of information can clouddecision-making about regulatory policy. There are fourAPRN roles: nurse practitioner (NP), certified registerednurse anesthetist (CRNA), clinical nurse specialist (CNS),and certified nurse-midwife (CNM). All are registered nurses(RNs) with master’s or doctoral degrees who are certifiedto provide specific types of care for particular populations.While their scopes of practice can overlap with thoseof physicians, APRNs do not practice medicine; theypractice nursing. They seek the opportunity to practice tothe full extent of their education and training within theirprofessional scopes of nursing practice.See A Primer on Advanced PracticeRegistered Nurse (APRN) Practice for details.Barriers to APRN Practice (see p. 3)State practice acts, institutional rules, and federal statutesand regulations from the Centers for Medicare andMedicaid Services (CMS) prevent APRNs from practicing tothe full extent of their education and training. These barriersreduce access to care, create disruptions in care, increasethe cost of care, and undermine efforts to improve thequality of care. They affect the four APRN roles in a varietyof ways.Nurse Practitioner (NP). State supervision mandatesmay include requiring monthly face-to-face visits with asupervising physician, and restrictions on APRNs’ authorityto prescribe medications and medical equipment; CMSrules limit the services APRNs may provide in skillednursing facilities. Such restrictions reduce both NP andphysician time for patient care, put undue cost burdens onNPs, and create gaps in care for patients, especially in ruralareas.i An NP and her supervising physician providingprimary care in underserved areas of Texas musttake several hours away from patients each monthto comply with state law (see p. 4). In Vermont, CMS regulations that requirephysicians to do the admission assessments forskilled nursing care create extra costs, delays,stress, and potentially dangerous information gapsfor patients whose primary care providers are NPs(see p. 4).Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist (CRNA). Insome states, state laws and/or CMS regulations requirephysician supervision of CRNA anesthesia services. A rural hospital in Colorado welcomed its state’sdecision to opt out of the CMS requirement thatphysicians supervise CRNAs working in hospitalsand ambulatory surgery centers (see p. 5). Although CMS has explicitly authorized directpayment to CRNAs for pain management services,some Medicare Administrative Contractors denypayment to CRNAs for these services (see p. 5).Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS). Some states do notrecognize CNSs as APRNs. This limits CNSs to the scopeof practice designated for RNs, prohibiting them fromprescribing medications or ordering lab work and durablemedical equipment. A Pennsylvania CNS has made impressivestrides in addressing heart failure, but statepractice barriers limit her ability to build on thoseimprovements and reduce the costs of care at thehospital where she works (see p. 6).Certified Nurse-Midwife (CNM). The availabilityof CNMs is constrained by mandatory collaborativeagreements between CNMs and physicians, the refusal ofsome hospitals to grant privileges, reduced reimbursementfrom some private payers, and a lack of access toaffordable liability insurance.

March 2017 In Georgia, a collaborative group practice ofobstetrician-gynecologists and CNMs has radicallyimproved birth outcomes for rural women, but statepractice restrictions discourage many of the state’sCNMs from practicing midwifery (see p. 6).The Costs of Collaborative Practice Agreements(see p. 7)The name collaborative practice agreement (CPA) maygive policymakers the false impression that CPAs mandatecollaboration in the care of individual patients. They donot. Instead CPAs spell out the restrictions that will governan APRN’s practice and the terms—which can varysubstantially—under which the collaborating physician willinteract with the APRN.Many states require APRNs to enter into a CPA witha physician in order to practice. The stated purposeof requiring CPAs is to protect the public, but there isno evidence to show that CPAs serve this function.Meanwhile, these legal agreements impose significantcosts on providers and patients. Physicians often charge APRNs for collaborativeservices. The cost of CPAs is unregulated and canbe onerous, amounting to thousands or even tens ofthousands of dollars a year (see p. 7). Many physicians hesitate to enter into collaborativeagreements for fear of incurring additional liability(see p. 7). Laws that limit the distance (for example, 50miles or less) permitted between APRNs and theircollaborating physicians discourage APRNs fromopening practices in rural areas where they are mostneeded (see p. 7). The termination of a collaborative agreement when aphysician moves, retires, or suddenly leaves practicecan create gaps in care. When this occurred inMassachusetts, patients resorted to hospital-basedemergency care (see p. 7). Insufficient availability of collaborating physicianslimits the opportunity to scale up proveninterventions that use APRNs to improve quality andreduce costs. A CMS-funded project in Missouri isexperiencing these growing pains (see p. 8). States with restrictive APRN practice acts mayalso incur a workforce penalty, since states withfewer restrictions appear to be more successful inattracting APRNs to work there (see p. 8).A Legislative Compromise (see p. 8)Transition-to-practice periods (TPPs), currently in placein ten states, represent a political compromise. TPPsallow new APRNs to apply for full practice authority afterpracticing for a given number of years and/or a minimumnumber of hours under the supervision of a physician, orin some cases, an experienced APRN. Although there isno evidence to support delaying entry into full practice forall APRNs, some nurses welcome the idea of creating truetransition-to-practice programs for newly certified NPs.These programs would be guided by more experiencedAPRNs and be educational, rather than legal, in nature.Veterans Administration Changes Regulation ofAPRN Practice (see p. 9)To improve access to care at the Department of VeteransAffairs (VA) Veterans Health Administration, VA issued afinal rule at the end of 2016 that would grant APRNs inthree of the four roles (NP, CNM, and CNS) full practiceauthority when acting within the scope of their VAemployment, regardless of state restrictions. VA noted thatthe decision to exclude nurse anesthetists “does not stemfrom the CRNAs’ inability to practice to the full extent oftheir professional competence, but rather from VA’s lack ofaccess problems in the area of anesthesiology.”Other Recent Breakthroughs (see p. 10)Since 2010 nine states have granted their NPs fullpractice authority. As of March 1, 2017, 22 states andthe District of Columbia allow NPs full practice authority.At least 12 states are currently considering legislationto remove practice barriers for one or more APRN roles.The National Council of State Boards of Nursing providesmodel legislation based on the APRN Consensus Model tofacilitate this process.Endorsements from the Federal Trade Commission,National Governors Association, AARP, AmericanEnterprise Institute, American Hospital Association, RobertWood Johnson Foundation, The Heritage Foundation, andothers have also lent weight to the arguments in favor ofremoving APRN practice barriers. So has a growing bodyof research suggesting full practice authority for APRNsmay reduce costs and improve access to care.Remaining Challenges (see p. 10)Practice barriers persist—not just in laws and regulationsbut also in institutions’ decisions about who will practicewithin their walls and insurers’ decisions about who willbe paid for delivering which services. The IOM Futureof Nursing report identified steps that Congress, statelegislatures, and federal agencies could take to removeAPRN practice barriers. These recommendations remainrelevant today.ii

CHARTING NURSING’S FUTUREClearing Up MisperceptionsOn May 25, 2016, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) issued a proposed rule thatwould allow advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) “full practice authority,” that is,the ability to provide—anywhere in the United States—the full range of services they areeducated and certified to deliver.The proposed rule broke new ground bypreempting those state laws that restrict whatAPRNs may do without physician supervision.In The Hill, an online publication coveringfederal news, veteran Michael Watson, DNP,FNP-BC, U.S. Navy reservist, declared,“[A]ll the proposal does is free APRNs to dothe job we were educated and trained todo, in exactly the same way we already doit as active-duty members of the military.”Yet the regulation—conceived as a meansto extend more timely care to veterans byincreasing access to APRNs within theVA system—generated public statementsfrom prominent organizations, includingthe Robert Wood Johnson Foundation,AARP, American Medical Association, andAmerican Society of Anesthesiologists, aswell as an unprecedented 220,000 commentsfrom individuals, both for and against.Why did this proposed regulatory changeprovoke such strong responses?Photo: U.S. Army by SGT Kalie JonesA certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA) deployedwith the U.S. Army in Iraq provides anesthesia for a patientin preparation for surgery.Historical tensions between portions of theorganized medical and nursing communitiesare partly to blame, but much of the publicis also uninformed or misinformed aboutwho APRNs are and what they do. The term“nurse” is broadly applied to certified nurses’aides, licensed practical or vocational nurses,registered nurses (RNs), and APRNs, yeteach type of “nurse” has vastly differenteducation, certification, and licensurerequirements. This creates confusion andWhat Recent Research ShowsTo date, most scope-of-practice research has focused on NPs. This growing body ofscholarship suggests that removing restrictions on NP practice has the potential to reducecosts and improve access to care without compromising quality. A study of NP-delivered care in health centers suggests that “NP care is comparable tophysician care in most ways and that the quality of NP-delivered care does not significantlyvary by states’ NP independence status.”Kurtzman ET, Barnow BS, Johnson JE, Simmens SJ, Infeld DL, Mullan F. Does the regulatory environment affectnurse practitioners’ patterns of practice or quality of care in health centers? Health Services Research. 2017;52(1pt2): 437-458. A 2015 study of Medicare data provides new evidence that care for beneficiaries managed byNPs costs less than care for similar beneficiaries managed by physicians.Perloff J, DesRoches CM, Buerhaus P. Comparing the cost of care provided to Medicare beneficiaries assigned toprimary care nurse practitioners and physicians. Health Services Research. 2016; 51(4). A working paper on wages, employment, costs, and quality suggests that “[M]ore restrictivestate licensing practices [for NPs] increase the costs of medical care, change wages andemployment patterns, and do not appear to influence health care quality as measured bychanges in the infant mortality rate and in malpractice insurance premiums.”Kleiner MM, Marier A, Park KW, Wing C. Relaxing Occupational Licensing Requirements: Analyzing Wages andPrices for a Medical Service. National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER Working Paper No. 19906; 2014. A systematic review of the impact of state NP scope-of-practice regulations on health caredelivery concludes “[R]emoving restrictions on NP scope-of-practice regulations could be aviable and effective strategy to increase primary care capacity.”Xue Y, Ye Z, Brewer C, Spetz J. Impact of state nurse practitioner scope-of-practice regulation on health caredelivery: Systematic review. Nursing Outlook. 2016; 64(1): 71–85.2Myth No. 1Opponents of full practice authority say itwould allow APRNs to practice medicinewithout supervision despite having receivedfar fewer hours of formal education thanphysicians receive.What Policymakers Need to KnowIt’s true that it takes fewer years of formaleducation to become an APRN than tobecome a physician, but APRNs are notpracticing medicine. They are practicingnursing. Even though many of their servicesoverlap with those of physicians, APRNs donot routinely perform surgery, diagnose rarediseases, manage high-risk pregnancies, orengage in a host of other complex medicalinterventions. APRNs are appropriatelyeducated to provide the scope of servicesfor which they are licensed and certified, and,like other health professionals, they makereferrals to their physician colleagues andother clinicians when their patients’ needsfall outside their scope or competence.can make it difficult to appreciate whatdistinguishes APRNs from other nurses.Advanced Practice Nursing 101APRNs make up an estimated 5-10 percentof the nursing workforce. These highlyskilled clinicians are licensed RNs withmaster’s or doctoral degrees, and they arecertified to provide various types of care(for example, primary, mental health, oranesthesia) for distinct populations (such aschildren, adults, or people with cancer). (SeeA Primer on Advanced Practice RegisteredNurse (APRN) Practice for details.)APRN professional scopes of practice—theservices they are educated and certified toprovide to which groups of patients and inwhat settings—both overlap and complementthose of their physician colleagues. Bothtypes of providers examine patients,diagnose and treat illnesses, prescribemedications, and promote their patients’health. APRNs are not prepared to provideall health care services to all people—nor dothey aspire to. They are seeking to removethe legal, regulatory, and institutional barriersthat hamper their ability to provide the carethat falls within their scopes of practice.

March 2017Barriers to APRN PracticeState restrictions on APRN practice vary, from pro forma physician oversight of APRN prescribing to periodic onsite physician supervision.These relationships, often spelled out in “collaborative practice agreements,” can be burdensome and costly, and finding “collaborating”physicians can be a challenge (see p. 7). These mandates may also give policymakers and the public the false impression that physiciansoversee APRN decision-making.“It was clear to me that policymakersthought physicians were signing off on everyprescription NPs were writing,” says NPMary Chesney, PhD, APRN, FAAN, clinicalprofessor at the University of Minnesota, whoadvocated for recent changes to restrictiveAPRN practice laws in her state. “They didn’trealize that a collaborative practice agreementas defined in our state was just a formaldocument listing which categories of drugsthe NP was able to prescribe.”Meanwhile, Chesney and others point outthat true APRN/physician collaboration isalready a standard feature of patient care.Communication and referrals occur betweenthe appropriate clinicians at the appropriatetimes based on their clinical judgment—notbecause of legal mandates or restrictionson reimbursement, but because all healthprofessionals are bound by professionalcodes of conduct to serve their patients’ needs.In most states the Board of Nursing (BON)regulates nursing practice, but four stateshave “joint regulation.” This means thatthe state Board of Medicine (BOM) alsohas a say in regulating nursing practice.Even in states where the nursing professionregulates itself—as is the case with mosthealth professions—the BON and BOM oftencollaborate in writing nursing practice rules,a process known as “joint promulgation.”“Joint regulation raises a fundamental issue:whether one profession should be subjectto regulation by another profession,” saysLewis and Clark College Law School visitingprofessor Barbara Safriet, JD, LLM. “As forjoint promulgation, we’ve seen exampleswhere this delayed implementation of lawsrelated to APRN practice for several years.”Variation Among State RegulationsAcross the country, a patchwork ofregulations dictating the circumstancesunder which APRNs may practice hascreated inconsistencies in access to highquality, cost-effective health care. The mapon page 1 (see Figure 1) reflects the practiceenvironment for NPs alone, but maps of thepractice environments of the three otherAPRN roles show similar variation. Differinglaws and regulations governing whetherAPRNs may write prescriptions—and forwhich drugs—complicate the picture.In addition, institutional policies, federalrules governing Medicare and Medicaidreimbursement, and decisions by privateinsurance carriers limit the ways in whichAPRNs may serve their patients.While these restrictions ostensibly aim toprotect consumers, research consistentlyshows that granting full practice authorityto APRNs does not create a tier of “secondrate” care, as opponents have argued.Photo: Will Kirk/homewoodphoto.jhu.eduAs expert clinicians, clinical nurse specialists (CNSs) oftencollaborate with nurses throughout hospitals to improvequality and safety within health systems.“It is worth noting that there has not been anuptick in malpractice claims or safety andquality problems in states that have grantedAPRNs full practice authority,” says Chesney.“Instead people have greater access to care,and that care is effective and efficient.”For More InformationPhillips S. 29th Annual APRN Legislative Update. TheNurse Practitioner. 2017; 41(1).Summers L, Bickford C. Nursing’s Leading Edges:Specialization, Credentialing, and Certification of RNsand APRNs. American Nurses Association; 2017.Safriet BJ. Federal Options for Maximizing the Value ofAdvanced Practice Nurses in Providing Quality, CostEffective Health Care. In: Institute of Medicine. TheFuture of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health.National Academies Press; 2010: Appendix H.Wide Variation; Common ThreadsPractice barriers vary widely, and they arecontingent on an APRN’s role, employmentsetting, and state. The following pages profilea few of the practice barriers that affectAPRNs. These examples do not represent thetotal array of barriers that prevent APRNs frompracticing to the full extent of their educationand certification. Nevertheless, these profileshighlight some common threads and illustratethe ways in which practice barriers:Photo: Mark Hoffman, 2015 Journal Sentinel Inc.,reproduced with permissionPhoto: Sarah GloverNurse practitioners (NPs) work in hospitals and a wide variety of outpatient settings, and they have been instrumental inmaking primary care and other services available in the community. The NP at left is based in a clinic housed in a YMCA ina low-income neighborhood of Milwaukee. The NP at right frequently makes house calls as part of the transitional care sheprovides recently hospitalized patients. reduce access to care, create disruptions in care, increase the cost of care, and undermine efforts to improve thequality of care.3

CHARTING NURSING’S FUTUREHow Practice Barriers Differ by APRN RoleState Law Puts Thriving Practice at Risk Role: Nurse Practitioner (NP) Location: Texas Barrier: Requirement that aphysician provide writtenauthorization for an APRN todiagnose patients or prescribemedicationsBefore Holly Jeffreys, DNP, APRN, FNP-BC,opened the Family Care Clinic of Panhandlein 2009, many of the area’s residents hadgone three years or more without receivinghealth care. Even before the town of 2,600lost its health clinic in 2006, access tocare was sporadic. Area residents wouldsometimes show up for scheduled visits onlyto find that their providers had been pulled towork at the hospital an hour away.When Jeffreys opened her clinic, 22 patientsarrived on the first day; by the end of theweek, she’d cared for more than 100 people.“Some were patients with diabetes, highblood pressure, and cholesterol issues, andthe last time they had had meds was threeyears earlier,” Jeffreys says.The Family Care Clinic of Panhandle nowmanages the care of more than 11,000patients. Yet rather than facilitating the effortsof qualified practitioners such as Jeffreys,Texas law creates obstacles that make itdifficult for NPs to establish primary carepractices. Texas is one of 12 states thatstill require supervision, delegation or teammanagement by a physician in order for NPsto provide patient care. While a 2013 lawsomewhat eased supervisory requirements—physicians, for instance, are no longerrequired to be within 75 miles of the NPs theysupervise—collaborating NPs and physiciansare required by law to have monthly face-toface visits until they have worked togetherfor three years. After that, visits mustoccur quarterly and may be conducted viavideoconferencing, if desired.In practice, these requirements keep bothJeffreys and her supervising physician frommaximizing the time they spend on patientcare. The physician is based in Amarillo—afederally designated primary care shortagearea—but has to take a half-day off eachmonth to travel to Panhandle for face-to-facereviews, since he hasn’t worked with all theNPs in the practice for the required threeyears.“We wouldn’tanticipate a grocerystore opening in arural or underservedarea if they had toget an arrangementfrom Safeway everyyear in order tooperate, yet that’swhat we’re asking nurse practitioners to dowhen we link their ability to provide care,and patients’ ability to obtain services, toanother provider.”–Tay Kopanos, DNP, FNP, Vice-Presidentof State Affairs, American Academy ofNurse PractitionersJeffreys also has to pay him for his time,adding to the financial stress she faces asa small business owner. Jeffreys’ regularoverhead includes the salaries of 15employees. If her supervising physiciandecided to end their arrangement, or wassuddenly unable to practice, Jeffreys wouldhave to immediately stop seeing patients. Herexpenses, of course, would not immediatelycease, nor would the community’s need forcare.Federal Regulations Create Confusion, Inefficiency in Skilled Nursing Facilities Role: Nurse Practitioner (NP) Location: Vermont Barrier: Medicare stipulation thatonly physicians—not NPs—maycertify patients’ need for skillednursing care and conduct patientintake assessments and every otherroutine visitMichele Wade, MSN/Ed, APRN, AGNP-C, anNP at Rutland Health & Rehab in Vermont,spends far more time than she’d likeexplaining regulations to residents andfamilies.“I recently fielded a call from a newresident’s family that was extremely upsetthat a physician they did not know did anadmission assessment on their 90 -yearold mother and billed for a nursing homevisit,” Wade says. Under Center for Medicareand Medicaid Services (CMS) guidelines,physicians are the only providers allowed4to conduct the comprehensive admissionassessments required for Medicare-coveredskilled nursing care. As a result, the woman’slong-time primary care provider—an NP—waseffectively barred from helping the familyduring this time of transition.These circumstances create inefficiencies,Wade says, with the potential to delay careand put patients at risk. She recently noticeddifferences between the medication listprovided by another new resident and theone provided by the admitting hospital. Shecalled the patient’s primary care provider—anNP in private practice—and learned that thepatient required medication for both bipolardisorder and diabetes, two conditions thatweren’t even mentioned in the hospitaldischarge notes. The NPs straightened outthe patient’s medication and care plan duringthe call; then a few days later, a physicianwho did not know the patient conducted therequired admission assessment, signed themedication regimen, and was paid for both,even though the NPs had already reconciledthe medications.Barriers written into CMS guidelines mayalso inadvertently inhibit systemwideimprovements in care. Research showsthat including NPs on long-term care teamsreduces hospitalizations, increases residentand family satisfaction with the quality ofcare, and may reduce costs by minimizingthe unwanted use of treatments at the end oflife. Yet nursing homes shy away from hiringthese providers because NPs employed bynursing homes cannot legally certify patientsfor Medicare coverage or conduct mandatoryassessments—even though similarlyemployed physicians can.For More InformationCenters for Medicare and Medicaid Services,MLN Matters Article SE1308 (2013)

March 2017How Practice Barriers Differ by APRN RolecontinuedAn Essential Provider in Rural America Role: Certified Registered NurseAnesthetist (CRNA) Location: Colorado Barriers: Physician supervisionrequirement for anesthesiaservices in some settings; denialof some CRNA claims for painmanagement servicesLike anesthesiologists, CRNAs provide bothpain management services and anesthesia,including during relatively rare and difficultsurgeries. In some settings, anesthesiologistsoversee CRNAs who deliver direct patientcare. In other settings—especially inunderserved areas—CRNAs provide highquality, cost-effective care without physicianoversight. The America

ChartingNursing’s Future The 2010 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health took a bold stand. It called for the removal of practice barriers—laws, regulations, and policies that prevent advanced p