Transcription

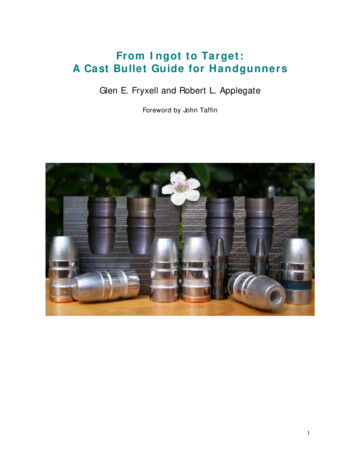

From Ingot to Target:A Cast Bullet Guide for HandgunnersGlen E. Fryxell and Robert L. ApplegateForeword by John Taffin1

From Ingot to Target: A Cast Bullet Guide for HandgunnersA joint effort by Glen E. Fryxell and Robert L. ApplegateForeword by John TaffinAbout the Authors . . . Pg 5Acknowledgements . . . Pg 7A Few Words about Safety . . . Pg 9Chapters1. Introduction: A Brief History of Bullet Casting . . . Pg 112. Bullet Casting 101 . . . Pg 193. Alloy Selection and Metallurgy . . . Pg 274. Fluxing the Melt . . . Pg 375. Cast Bullet Lubrication . . . Pg 416. Throat and Groove Dimensions . . . Pg 567. Leading . . . Pg 588. Idle Musings of a Greybeard Caster . . . Pg 669. Moulds and Mould Design . . . Pg 7310. Gas-checked vs. Plain-based Bullets . . . Pg 8711. The Wadcutter . . . Pg 9712. The Keith SWC . . . Pg 10613. Casting Hollow Point Bullets . . . Pg 11814. Making Cast HP moulds . . . Pg 13115. Hunting with Cast Bullets . . . Pg 13616. A Few of our favorites . . . Pg 148Appendix A: How old is your mould? . . . Pg 173Above: Left to rightMP Molds Clone of the RCBS 45 caliber 270 Gr. SAASAECO #382 35 caliber 150 Gr. PB SWCSAECO #068 45 caliber 200 Gr.SAECO #264 6.5mm 140 Gr. SP GCOn the cover:Two RCBS 44 Caliber 300 Gr. Flat Point Mould Halves.One Mould was converted to Cramer style HP by Erik Ohlen with gas check shankremoved from one cavity, casting one HP GC and one HP PB.Second mould casting both cavities flat point, one plain base, one gas check.Two moulds, four cavities, four different styles of hunting bullets.This book is copy right protected (copyright 2011). All rights are reserved by the authors. No partmay be copied, reproduced or transmitted in any fashion without written permission of the authors.Cover and index page photography by Rick KelterPublished exclusively at www.lasc.us2

Foreword: by John TaffinIn many ways it seemed like only yesterday I began casting bullets. Infact it has been nearly one-half century since I started pouring that first batchof molten alloy into a single cavity mould, or mold if you prefer. It was in mymother's kitchen, at my mother's stove, next to my mother's refrigerator. Itwasn't long before the whole top half of the side of her refrigerator was coveredwith speckles of lead. Now my mother was the most fastidious of housekeepers,however she never complained. Looking back I can only assume she thought itbetter to have me making a mess in her kitchen rather than running arounddoing something of which she didn't improve.At the time I was working for a large wholesale warehouse catering toplumbing and building contractors. This gave me access to both 100# bars oflead and one pound bars of tin. There was also a reciprocal agreement with afew other businesses allowing employees from one place to purchase from theother at wholesale prices. From the now long gone Buckeye Cycle I was able toorder two Lyman single cavity molds, #454190 for the .45 Colt and #358311for the .38 Special; a Lyman #310 “Nutcracker” Reloading tools with the diesfor both .45 Colt and .357 Magnum, and I was ready to cast bullets. Those twomolds are gone as it wasn’t long before I graduated to multiple cavity moulds;however, I still use that #310 tool to pop primers from cartridges cases firedwith black powder.Living as we do in the Instant Information Age, it is sometimes difficult tobelieve how little information was available or how difficult it was to find in themiddle of the 20th century. I had read Elmer Keith’s “Sixgun Cartridges andLoads” which gave me the very basics. Much of the rest I learned over the nextfour decades by trial and error and casting and shooting thousands uponthousands of cast bullets in hundreds of sixguns. Casting bullets opened allkinds of doors for me. Most importantly, casting allowed the shooting of vastamounts that would never have been had I found it necessary to buy my bulletsfrom other sources. The only way to become even reasonably adequate with asixgun is by shooting a lot, and only casting my own bullets allowed this. All ofmy shooting experiences, the vast majority of which has been with home castbullets eventually led to my position as Field Editor with “AmericanHandgunner” and Senior Field Editor with “Guns” magazines. Along the way, Inot only managed to acquire a pretty good knowledge of cast bullets but also aworking collection of approximately 250 bullet moulds from virtually everymanufacturer. With this background in mind I now turn to the volume you holdin your hands.Glen Fryxell is a chemist by trade and a bullet caster by choice. He knowsmore about casting bullets than anyone else I know. Rob Applegate is both anexcellent gunsmith as well as a maker of custom bullet moulds. Put the two ofthem together, and virtually every aspect of cast bullets is covered in whatcomes the closest to ever being called “The Complete Book of Cast Bullets.”Only their modesty prevents them from using this title and instead of goingwith “From Ingot to Target: A Cast Bullet Guide for Handgunners.”I found two things of major importance as I read this book. 1) The things3

I've learned about cast bullets and casting bullets are true. 2) There was stillmuch I needed to learn. Both what I know and what I needed to know arefound in this book. Any well-informed sixgunner, even if they never intend tocast their own bullets, will find information here that simply make shootingmore enjoyable. Which is better, plain-based or gas checked bullets? Why dosoft bullets shoot well while hard bullets lead the barrel, and vice versa? Howdoes bullet lube work? What is this mysterious thing called flux? How importantare cylinder throat and barrel dimensions? Do cast hollow point bullets reallywork? Can one hunt with cast bullets, and if so which ones work the best?As important to me as the how-to information is the historicalbackground. Over the years many men have contributed to our knowledge ofbullets in general and cast bullets in particular. In these pages you will find suchcast bullet pioneers as Elmer Keith, Phil Sharpe, Jim Harvey, Ray Thompson,Veral Smith, and my dear friend, J.D. Jones. Understanding their contributionssimply makes shooting sixguns all that more enjoyable.If you have never cast a bullet but are planning to start, read this bookfirst. Keep it at hand, and refer to it often. If you are an experienced bulletcaster, stop; do not cast another bullet until you have read this book. Youmight be surprised at how much you have to learn. Rob and Glen have done anadmirable job of gathering and presenting valuable information on what manythink is a somewhat mystical or magical art. The doors are open, the lights areon, and the magic and mystery have been dispelled. This volume is a mostvaluable addition to both my loading room and my library. I expect all otherdedicated sixgunners to also find this to be true.John TaffinBoise, Idaho4

About the authors:Glen Fryxell has been fascinated with guns and hunting his entire life,and started hunting early, primarily with a bow and arrow during his teenyears, and more recently with handguns. He obtained his B.Sc. in chemistryfrom the University of Texas at Austin in 1982, and his Ph.D. in chemistry fromthe University of North Carolina in 1986. Professionally, his interests havecentered around environmental chemistry, nanostructured materials, molecularself-assembly and biomimetic processes. On the personal side, he is a hunter,shooter, reloader, and guitar player (of marginal ability). He has been castingbullets and reloading since the 1980s, and has hunted primarily with handgunsover the last 20 years, taking dozens of head of big game and thousands ofvarmints, over much of the western US. His fascination with the use andperformance of cast bullets in the hunting fields, in conjunction with histechnical background in materials science and chemistry, led him to study thefascinating field of metallurgy in his spare time in an effort to more deeplyunderstand bullet performance in the hunting fields.Rob Applegate was born with an innate passion to explore anythingmechanical. If it moved, or had moving parts, he could not resist thetemptation to dismantle all of the various parts in their entirety and find thecauses of all the various movements and the forces behind the movements. Inshort, he was fixated on levers, grooves and pressures.The keen interest he had in mechanics manifested itself with firearms. Asa little boy, he sat in stillness and watched with awe as his father patientlydismantled his sporting weapons and carefully cleaned and oiled each partbefore reassembling the rifle, revolver or shotgun upon which he was plying hisgifted skills. This interest continued throughout all of his young life and beyondhigh school.His post high school education was centered around learning as much aspossible about mechanics and eventually led to further education as to all of thevarious methods used to make the parts necessary to assemble machines of alltypes. After twenty five years of working "under the time clock", theopportunity presented itself for Rob to become a full-time gun maker.Being an avid shooter and tireless experimenter, Rob eventually becameinterested in casting bullets for a couple of old rifles passed down through thefamily to his dad. Bullets for the .40-82 Winchester were not readily availableback in the late '50s and '60s, so Rob decided to he would make his own fromthe Winchester mould that was with the old '86. At that time, all that Rob knewabout casting bullets was that "you melt lead in an iron pot, poured it into amould, and after it cooled you opened the mould and out fell a bullet". Ahem, tosay that he had much to learn is an understatement! But learn he did. As timepassed, his skills and knowledge about casting bullets improved, along with thisskills and knowledge about machining and tool-making.Most of his work as a custom gun-maker centered around single-shot andlever-action rifles, as well as revolvers. Nearly all of his barrel jobs and relatedwork was for firearms that were dedicated solely for shooting cast bullets.5

Whether they were black powder cartridge rifles, or the highest quality castbullet bench rest rifles, the majority were to be used shooting cast bullets. All ofthe work on rifles and revolvers eventually led to the culmination of a dreamand desire that Rob had had since childhood -- to make a bullet mould. Once hehad refined mould-making to his satisfaction, he decided to make moulds on afull-time basis. For a number of years he made mould cherries and bulletmoulds. During these mould-making years he learned more about bullet designthan he thought possible. Eventually, several personal crises befell him, and theshop had to be closed. With most of these tragedies behind him, he would liketo share some of his knowledge with the bullet casting fraternity.With Glen Fryxell's excellent help in all aspects of the entire bullet castingscience, we have compiled a work that is hoped will provide assistance to thosewho desire to shoot cast bullets in handguns. Glen is one of Rob's closestfriends.6

Acknowledgements:I am a student of the gun; or perhaps more accurately, I am a student ofthe bullet. I learn something every time I cast, load or shoot. Such aneducation clearly did not take place in a vacuum. I have the unwaveringsupport of my lovely wife (who is still the nicest person I have ever met), acouple of great kids, and the most wonderful grandkids in the world (OK, so I’ma little biased!). My parents have always been loving and supportive teachers,who valued education (and paid for much of mine), ensuring that I would havethe ability to be a good provider. The resulting career has provided me with thewherewithal (and occasionally enough free time) to pursue those things thathave fascinated me since early childhood; guns, hunting, bullet casting andhandloading ammunition. Building upon that foundation are the contributions ofa multitude of teachers, who have taught me these things, as well asgunsmithing, metallurgy, machine work and the art of integrating all of thesedisciplines in the pursuit of my own personal vision of ballistic perfection. Thelist of such teachers is far too long for any sophomoric attempt at completeness, but there are several men that I have been privileged to call friend whoseguidance and insights must be acknowledged; Colonel Loveless of PleasantAcres (College Station, Texas), who taught me marksmanship and ethics as apart of the NRA Junior Marksmanship Program when I was growing up back incentral Texas; Dale Harber, who adopted me as a “kid brother” and took mehunting and nurtured my fascination with guns and handloading; Reo Rake,who got me started handloading and taught me the joys of the lead pot; LyleEckman, who taught me much, including how to shoot, listen and teach (onceagain, as a part of the NRA Junior Marksmanship Program); Dave Ewer, who ispatiently teaching me the art of gunsmithing, and has helped me rediscover thejoy of plinking; and John Taffin, for his guidance, advice and encouragement,for contributing to this book and for being a shining example of what agentleman and gun-writer should be. Each one of these men is a crack shot,seasoned competitor, knowledgeable handloader and darned fine man. Thankyou gentlemen.Lastly, I would like to thank Rob Applegate for being the ideal partner towrite this book with. Rob is the kind of man that is met all too rarely thesedays, unfortunately. He is a hard-working, good Christian man. He is honestand industrious not just because he was taught that was the right way for aman to handle himself, but because he simply cannot operate any other way. Itis his fundamental nature. He is a quiet gentleman, usually of few words, butwhen he speaks I listen, because Rob is a goldmine of knowledge on all thingsballistic (among other things). Rob is the kind of friend that you can walk formiles through the mountains with and never say a word, because nothing needsto be said -- the mountains, wildlife, wind and clouds speak volumes, and hehasn’t the rudeness to interrupt. He’s the kind of man that can be caught a mileand a half from the truck in his shirt sleeves in a surprise rainstorm and inconversation during the soggy walk back never once complain about theweather. He’s a giddy little boy who can spend hours out in his shop talkingabout the vice he made to cut mould blocks with, and while he’s justifiablyproud of his gadget, his real joy comes from the fact that his skills have createdthe ability to build new things, and to build them right. Much of Rob’s liferevolves around building things. My Mother taught me many years ago, “Any7

fool can destroy. It takes a real man to build.” Rob is a real man, a man whobuilds. He is a meticulous craftsman whose attention to detail is exquisitelyapparent from the exceptional quality of his work. His nickname is“Persnickety”, and for good reason. Rob, we live too far apart. We should gettogether more often; you and Marilyn are special people. Thanks for everything,my friend.This book is a partial summation of these educational gifts, my primarycontribution being my fascination with the subject and my unquenched desire tolearn (and shoot) more. If the reader finds this book enlightening, educationalor in some way of value, it is simply a reflection that I have been blessed withso many good teachers. Any flaws in the presentation are clearly my own.Glen FryxellKennewick, WashingtonWithout Glen, this book would most likely have never happened in itscompleteness of text on the subject of casting bullets for handguns. Hiseducation in the sciences put a finality to the quandary about how and whyalloys perform (or don't perform), both in the mould and in the bore. Glen isone of a handful of friends I have who looks past my stubbornness and basicanti-social behavior to have many deep discussions about cast bullet use andperformance.To the men who were responsible for my education and training (myfather, Uncle Rex, great-Uncle Gus Perot, etc.), I have said thank you andfarewell, for they have all passed from this earth, as I will one day also.I have a few of the dearest friends anyone could hope for. To them I owemany thanks, not only for their encouragement for me to keep writing, but inmany other things as well. For anyone who learns anything from this book, orwho receives much needed help of advice, you can thank my lovely wife Marilynfor sorting out my hand-written scribbling and putting it all into an intelligibletype-written manuscript. Without her, none of this would be possible.Each and every day, I thank God for the wonderful life I've had and forhis Son, Jesus, the Great Forgiver.Robert L. ApplegatePrineville, Oregon8

A few words about safety OK, let’s get one thing straight right from the beginning: casting bulletsfrom molten lead can be dangerous. So can handloading ammunition, shootinga gun, driving a car, or operating power tools. However, if one thinks about thehazards associated with each of these practices, recognizes what and wherethey are, applies a little common sense, follows established safe practices andtakes appropriate preventative precautions, the risks can be mitigated to thepoint that bullet casting is pretty much as safe as collecting butterflies. If youchoose to cut corners, ignore safety rules, be lackadaisical or just flat don’tthink about what you‘re doing, you will get burned, and you may well poisonyourself and those around you. Just like handloading, bullet casting is as safe oras dangerous as you make it.Bullet casting inherently involves hot metal, both the molten alloy thatwe fashion bullets from and the hot moulds and lead pots. Leather gloves are agood idea (and remember, a hot mould looks just like a cold mould, this is whywe put wooden handles on them!). Even very small splashes of molten lead cancause nasty burns and leather does wonders for preventing them. And lead potsdo splash -- when adding metal, stirring in flux, or if (heaven forbid!) theyencounter any moisture. Keep all sources of moisture well away from your leadpot! A single drop of water can empty a 10 pound lead pot explosively, coatingeverything in the immediate vicinity with molten lead. If your lead pot is out onan open work bench, even minor splashes mean that safety glasses are a must.I cast with my lead pot wholly enclosed in a laboratory grade fume hood, with aglass sash in place between my face and the lead pot. I leave the little leadsplatters in place on the glass sash as a reminder to myself as to how easilythese things happen, and for instructional purposes for any new casters that Imay be teaching.Good ventilation is very important to the bullet caster. My fume hoodalso serves to provide suitable ventilation, not only for the smoke coming offthe pot but also for the heavy metal fumes emanating from the pot. Lead fumesare an obvious concern, but more subtle is the fact that wheel-weight alloy alsocontains small amounts of arsenic. Arsenic is kind of a quirk in the periodictable in that it forms an oxide that is more volatile than the metal, and in factat lead pot temperatures, some forms of arsenic oxide are fully gaseous, so ifthe arsenic gets oxidized all of it evaporates from the lead pot and is easilyinhaled. Use of a reducing cover material helps to prevent this oxidation (seechapter on fluxing).Fumes are not the only exposure vector that we need to be aware of,teething children like to put anything small and chewable into their mouths,especially if it’s bright and shiny. This includes cast bullets and discardedsprues, making housekeeping an important issue if small children have accessto your casting area. This is easily dealt with, keep the sprues contained (heckjust recycle them!) and keep the bullets packaged and out of reach of smallfingers. Big fingers are an issue too: wash your hands thoroughly after eachand every casting session, and again before you eat.We’ve all heard about lead poisoning, but what does it really look like?9

The symptoms of lead poisoning in adults include: loss of appetite, a metallictaste in the mouth, constipation, pallor, malaise, weakness, insomnia,headache, irritability, muscle and joint pain, tremors and colic. Lead poisoningcan cause elevated blood pressure, sterility, and birth defects. The mostsignificant site of lead toxicity is the central nervous system, but lead poisoningalso impacts the red blood cells and chronic exposure to lead most often resultsin kidney problems. A child’s body is more efficient at absorbing and retaininglead than is an adult’s, and lead gets stored in a child’s growing bones. The netresult is that children are far more vulnerable to lead poisoning than are adults,and since their central nervous systems are still growing and developing, theimpact of lead poisoning on a child’s life can be far more severe than it mightbe for an adult, and may include brain damage, mental retardation, convulsionsand coma. Responsible handling of lead can prevent these exposures,symptoms and health hazards.Remember, safety first. Think about what you are doing, takeappropriate precautions, use adequate ventilation, and keep your lead out ofreach of small children. Bullet casting is a wonderful hobby and one that willallow you to get so much more out of your shooting, but just like handloading,bullet casting is only as safe (or as dangerous) as you make it.10

Chapter 1: IntroductionA Brief History of Bullet Casting: American IndependenceBullet casting contributed significantly to the independence of thewestern cowboy, trapper and mountain man. That independence is still valuabletoday. Just like the mountain man, once the modern caster buys a particularmould he can produce that bullet for the rest of his life, and he doesn’t have toworry about whether commercial bullet makers will alter or drop a particularfavorite from their line. The ability to produce countless thousands of identicalbullets for decades to come reveals what a miniscule investment a bullet mouldreally is.HistoryOriginally bullet moulds were made and sold by the firearms manufacturers themselves. Colt was an early player in the mould manufacturinggame, making ball and conical bullet moulds for their early cap-n-ball revolvers.Shortly after the advent of the self-contained centerfire (i.e. reloadable)cartridge more sophisticated reloading tools became available. Soon after S&Wgraduated from rimfire cartridges to their centerfire Number 3 .44 American in1870, they also added loading tools, including bullet moulds, to their productline. In the Remington catalogs of the 1870s are listed bullet moulds made bythe Bridgeport Gun Implement Co. (BGI was a partner company, started around1870 specifically to make loading tools for Remington). Winchester startedmaking iron-handled bullet moulds in 1875 (and in a humanitarian gestureadded wooden handles in 1890). In their 1876 catalog, Sharps advertised bulletmoulds to make paper-patched bullets for their popular and powerful rifles.Marlin (Ballard) was also making moulds in the 1870s, and in 1881 enlistednone other than John M. Browning’s input for a mould/loading tool that hedesigned and patented, and was subsequently manufactured by Marlin. TheMaynard 1873 cartridge had a 5-piece case, very thick cartridge head andBerdan primer. The Maynard loading tools had a bullet mould, as well as a hookand a chisel for prying the spent primers out of the spent cartridge case. One ofthe more unique moulds from this era is that for the Maynard exploding bullet,a HP designed to be fitted with a .22 blank cartridge, advertised in the 1885Maynard catalog in .40, .44 and .50 caliber. The 1870s were indeed a time ofgreat change in the firearms industry.In 1884 John H. Barlow took his experience as a shooter and as a tooland die maker and founded the Ideal Company, offering his patented tong toolsto reload spent cases, and later separate bullet moulds for those using benchmounted presses. These bullet moulds were either single cavity, or 6- or 7cavity Armory moulds, all with fixed handles at this point.The landscape was changing dramatically in the firearms industry in thelate 1800’s and early 1900’s, and John Barlow kept pace with his contributions.His Ideal Handbooks (first published in the 1880's) were the first reloadingguides published in America, of critical importance as shooters moved into therelatively uncharted territory of the then new smokeless powders. In IdealHandbook #4 (published in 1890), he described the use of cast hollow-pointedbullets for enhanced performance on game animals. In Ideal Handbook #9(1897) he unveiled the now familiar mould numbering scheme for Ideal's first150 mould designs. In 1906, Barlow patented the first American gas-checked11

cast bullet designs to take advantage of the higher velocities available from thenew smokeless powders (described later that year in Ideal Handbook #17). InMay of 1910, after leading the IdealManufacturing Co. for 26 years, Mr.Barlow retired and sold the company toThe Marlin Firearms Co., with whom hehad worked closely for many years.Marlin sold Ideal a few years laterduring the first World War to PhineasTalcott (but Marlin remained involvedwith production of the IdealHandbook). By 1925 things were notNote the lack of alignment pins and the handgoing well and Phineas Talcott sold thecut vent lines.struggling Ideal Reloading ToolCompany to the Lyman Gun SightCorporation (founded by William Lyman in 1878), along with the rights to theIdeal Handbook (which was later renamed “The Lyman Handbook“ with #27,published in 1926). Lyman scaled up manufacturing capacity and continuedproduction of the Ideal line of bullets moulds, using the Ideal name into the late1950s. During this time Lyman introduced interchangeable mould blocks in theirsingle cavity moulds (first advertised in the American Rifleman in 1927, andcataloged in 1931), and phased out the older fixed handle style. In 1940-1(Ideal Handbook #34), Lyman added a special retaining pin to hold their hollowpoint plug in place during casting. Interchangeable double cavity mould blocksdidn’t appear until after World War II (first listed in the Ideal Handbook #36,which was published in 1949), followed soon thereafter by venting lines cut inthe faces of the mould blocks. Interchangeable 4-cavity mould blocks wereintroduced in 1958. Lyman continues to produce many of these mould designsto this day.Early Ideal rifle bullets weredesigned not only by John Barlow,but also by such notable shootersas Harry Pope, Col. TownsendWhelen, and Phil Sharpe, amongothers. In the early 1920s, avociferous northwestern cowboy,rancher and competitive shooternamed Elmer Keith went toAn Ideal Armory mould for the 360344 wadcutter.Belding & Mull with some of hisideas for experimental revolver bullets. Belding & Mull made the moulds(interestingly, B&M moulds were made out of solid nickel) and Keith assembledand evaluated many test loads using these bullets. Keith learned much fromthese experiments with cast bullet design, but he never quite got to where hewanted to be. In 1928, shortly after Lyman bought the Ideal Co., he turned toLyman and asked them to make some bullet moulds according to his optimizeddesigns. Thus was born the Keith SWC. The Keith SWC's have 3 equal widthdriving bands, a square-cut grease groove, a beveled crimp groove, a sharpwad-cutting shoulder, a compound-radiused ogive for stable long-range flight,and a healthy, meat-crushing meplat. They have proven themselves over thelast three quarters of a century as some of the finest revolver bullets of all12

time. The original Keith SWC was for his beloved .44 Special (#429421), butKeith/Lyman went on to produce similar moulds in other calibers (e.g. .357,.45, etc.) and in hollow-base and hollow-point variations.Similar fixed handle moulds were also made by the Yankee SpecialtyCompany. These were made out of bronze and were commonly cut with thesame designs as used by Ideal, including the Keith SWC's. Yankee Specialtymade 1, 2 and 3 cavity moulds, as well as HP moulds (they claimed to haveover 600 designs available). Yankee Specialty was in business from 1916 untilthe owner died in 1954, although their business volume after 1940 was small.Yankee moulds are commonly unmarked and have simple cylindrical woodenhandles that are wired on (although a few are reported to have ferrules).Things got busy on the American bullet casting scene in the secondquarter of the 20th century. George Hensley was a machinist involved in themanufacture of all sorts of things (like bicycles, a gasoline fired marine engine,etc.), as well as doing general machine work and repair, with his company thathe started in 1893. In 1932, he started turning out some top-notch mouldsfrom his shop in San Diego in response to the demand for multiple cavitymoulds needed by police departments. The P.D.'s had to supply practiceammunition for their officers and needed moulds capable of casting largernumbers of bullets than what was generally available at the time. The GreatDepression meant that budgets were tight, and affordable practice ammo wasa significant need, just as it is today.James Gibbs was a farm boy from theMidwest who was very mechanicallyinclined and was operating a smallgunsmithing shop on his own.James met up with George Hensley inthe late 1930s as a result of theircommon interest in firearms, and Mr.Hensley quickly saw James’ talentsA copy of the Ideal 452423, made by Yankeeand the two struck on an agreementSpecialty Co. with integral handles (Yankeefor James to help George out in theSpecialty also made a few moulds withinterchangeable blocks). This Depression-erashop making moulds. Hensley &mould is made from bronze, not iron.Gibbs worked together from 1938 to1940, when George became too oldto work in the shop. Eventually, he sold the business to James in 1950. Thepartnership of Hensley &

a little boy, he sat in stillness and watched with awe as his father patiently dismantled his sporting weapons and carefully cleaned and oiled each part before reassembling the rifle, revolver or shotgun upon which he was plying his gifted skills. This interest continued