Transcription

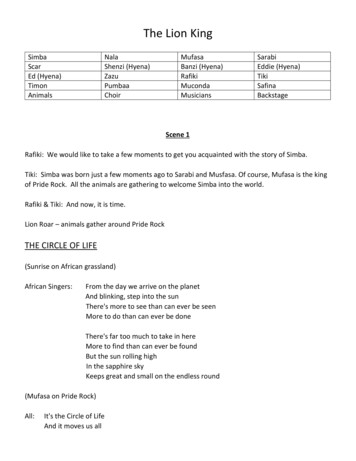

Pulling the Strings: King Hussein's Role during the Crisis of 1970 in JordanAuthor(s): Nigel J. AshtonSource: The International History Review, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Mar., 2006), pp. 94-118Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd.Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40110724 .Accessed: 13/10/2011 16:31Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at ms.jspJSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.Taylor & Francis, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The InternationalHistory Review.http://www.jstor.org

NIGELJ. ASHTONPullingthe Strings:KingHussein's Role duringtheCrisisof 1970 inJordancrisis that erupted in Jordan in September 1970 was a strugglefor survival for the Hashemite regime. Had King Hussein not succeeded in defeating the Palestinian guerrilla groups based inJordan, and the Syrianinvasion, he would have lost his throne. In turn, thecollapse of Hashemite Jordan would have provoked a wider regionalconflict, sucking in Israel, Syria, Iraq, and Egypt with dangerous consequences, including the possibility of superpower intervention.In the literature,Hussein's survivalin the face of this threatis explainedin terms of US and Israeli intervention. The US dimension of this thesis isbest summed up in Douglas Little's description of Hussein in an earlierarticlein thisjournal as a 'puppet in search of a puppeteer',1and the Israelidimension in Uri Bar-Joseph'sdescription of Jordan and Israel during the1948-9 war as the 'best of enemies'. This dual explanation has foundfavourwith commentatorsof very differentcomplexions. For some leadingPalestinianscholars, it reinforces a conception of the Hashemite regime asan illegitimate, Western-imposed, crypto-Zionist construct.2 Meanwhile,some Israeli historians, such as Moshe Zak, have used the crisis to arguethat Israel was the long-term 'Guardianof Jordan', even if the relationshipdid not become apparentuntil the signature of the Israeli-Jordanianpeacetreatyin 1994.3Henry Kissinger'saccount of the crisis, which provides the bedrock forthe 'puppet in search of a puppeteer' thesis, portrays it as a cold war confrontation with the Soviet Union in which he acted as the master chessplayer manipulatingthe local actors. It leaves little room for Hussein's owninitiative, even though Kissinger still expresses a healthy respect for Hussein's political skills.4What is missing in the existing literatureis a view of1 D. Little, 'A Puppet in Search of a Puppeteer? The United States, King Hussein, and Jordan, 195370', International History Review, xvii (1995), 512-44.2 See, e.g., R. Khalidi, 'Perceptions and Reality: The Arab World and the West', in A RevolutionaryYear: The Middle East in 1958, ed. W. R. Louis and R. Owen (London, 2002), pp. 195-7.3 M. Zak, 'Israel and Jordan: Strategically Bound', Israel Affairs, iii (1996), 39-60.4 H. Kissinger, WhiteHouse Tears (Boston, 1979); author's interview with Henry Kissinger, New York,2 June 2003.The International History Review, xxviii. 1: March 2006, pp. 1-236.cn issn 0707-5332 The International History Review. All InternationalRights Reserved.

The Crisis in Jordan95the crisis as it may have appeared to Hussein himself, whose actionsprecipitated the showdown with the fedayeen. This article will reassessHussein's handling of relations with the United States and Israel duringthe crisis. It will contrast his grasp of the intentions of the key regionalplayers with the more limited focus in Washington on cold war interests. Itwill also show that suspicion was the keynote of the Israeli-Jordanianrelationship during the crisis. Despite the stress placed on US and Israelibacking for his regime in the literature, it was Hussein's own forces thatrepelled the Syrian invasion, and expelled the PLO guerrillas. Hussein isthus cast here more in the role of puppeteer than puppet during the crisis.He * * * *Competition between the Hashemite regime and the Palestinian nationalmovement was not a new phenomenon in 1970. Before the outbreakof the1948 war, Hussein's grandfather, Abdullah, had made contact with theleaders of the Jewish community in an attempt to settle the political futureof Palestine. Controversy surrounds both his motives and the results.Abdullah's critics charge him with splitting the united Arab front andconniving in the creation of Israelin the hope of territorialaggrandizement.Others see him as a realist, who recognized that Zionism could not bedefeated and sought a compromise favourableto his own interests.1AfterIsrael's victory in 1949, Abdullah both tried to broker a permanent settlement and, in 1950, took the decision that ensured that the PalestinianIsraeli conflict would affectJordan's domestic politics as well as its foreignpolicy: the Union of the Two Banks, and the granting of Jordaniancitizenship to displaced Palestinians,left the Hashemites to solve the problem of how to ensure the loyalty of their new Palestiniansubjects. Abdullahpaid the highest price for his independent course. On 20 July 1951,he wasassassinated by a Palestinian gunman as he left Friday prayers at the alAqsa Mosque in Jerusalem.After Hussein ascended the throne in May 1953, the needs and demandsof the Palestiniansnot only constrainedhis freedom of manoeuvrebut also,periodically, threatened the survival of the Hashemite regime.2 Israel's1 See, e.g., A. Shlaim, Collusion across the Jordan: King Abdullah, the Zionist Movement, and thePartition of Palestine (Oxford, 1988); M. C. Wilson, King Abdullah, Britain, and the Making of Jordan(Cambridge, 1987); I. Pappe, The Making of the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1947-51 (London, 1992); U. BarJoseph, The Best of Enemies: Israel and Transjordan in the War of 1948 (London, 1987); E. Karsh,Fabricating Israeli History: The 'New Historians' (London, 2000); J. Nevo, King Abdallah andPalestine: A Territorial Ambition (Basingstoke, 1996); A. Sela, Transjordan, Israel, and the 1948 War:Myth, Historiography, and Reality', Middle Eastern Studies, xxviii (1992), 623-88; E. L. Rogan,'Transjordan and 1948: The Persistence of an Official History', in The Warfor Palestine: Rewriting theHistory of 1948, ed. E. L. Rogan and A. Shlaim (Cambridge, 2001), pp. 104-24.2 For useful overviews of the early years of Hussein's reign, see U. Dann, King Hussein and the

96Nigel J. Ashtoniron-fist reprisals against Palestinian infiltrators who crossed the 1949armistice lines,1 including its major incursions into the West Bank - atQibya on 14 October 1953, Qalqilya on 11October 1956, and Sam'u on 13November 1966 - angered Jordan's Palestinian subjects by exposing itsinability to protect them. When Britain tried in December 1955 to persuade Jordan to join the Baghdad Pact by offering military aid, the WestBank Palestinian ministers in Fawzi al-Mufti's cabinet threatened resignation.2The view of Britain'senvoy, General Sir Gerald Templer, was thatthey carecompletely blind to any aspect of the problem except the Israelissue about which they bleat continuously'.3 Nor were they unrepresentative. As Templer noted in his final report on his failed mission, 'theirlives would be in danger if they accepted Jordanian accession to the Pactwithout some compensatingadvantagefor the refugees.'4In the early 1960s, Hussein tried again to reconcile Palestiniannationalism with Hashemite rule over the West Bank. In December 1962, a WhitePaper presented to parliament by the prime minister, Wasfi al-Tall, anddrafted by Hazem al-Nusseibeh, a PalestinianfromJerusalem, proposed a'United Kingdom of Palestine and Jordan'. Little came of the proposal inthe short term, but Nusseibeh continued on Hussein's behalf to try tobuild a bridge to the Palestinian national movement under the leadershipof Ahmad al-Shuqayri. In the wake of the inauguralcongress of the Palestine Liberation Organization, held in Jerusalem in May 1964, Nusseibehinvited Shuqayri to Amman to discuss how Palestinians and Jordanianscould live within the same state. The sticking point, according to Nusseibeh, was Hussein's refusal to tolerate any political authority withinJordan that acted as a rivalfocus of loyalty for his Palestiniansubjects.5Challenge of Arab Radicalism: Jordan, 1955-67 (Oxford, 1989); R. Satloff, From Abdullah to Hussein:Jordan in Transition (Oxford, 1994). Further studies that address the Palestinian dimension duringthese years include Z. Shalom, The Superpowers,Israel, and the Future of Jordan, 1960-3: The Perils ofthe Pro-Nasser Policy (Brighton, 1998); A. J. Bligh, The Political Legacy of King Hussein (Brighton,2002); A. Abu Odeh, Jordanians, Palestinians, and the Hashemite Kingdom in the Middle East PeaceProcess (Washington, DC, 1999); C. Bailey, Jordan 's Palestinian Challenge, 1948-83 Political History (Boulder, 1984).1 See B. Morris, Israel's Border Wars:Arab Infiltration, Israeli Retaliation, and the Countdown to theSuez War (Oxford, 1993), and A. Shlaim, The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World (London, 2000),PP- 90-3, 233-7.2 See Satloff, Abdullah to Hussein, pp. 108-25; U. Dann, The Foreign Office, the Baghdad Pact, andJordan', Asian and African Studies, xxi (1987), 247-61; N. J. Ashton, Eisenhower, Macmillan, and theProblem of Nasser (Basingstoke, 1996), pp. 61-8; M. B. Oren, 4AWinter of Discontent: Britain's Crisisin Jordan, December 1955-March 1956', International Journal of Middle East Studies, xxii (1990), 17184.3 UK embassy, Amman, to F[oreign] O[ffice], 10 Dec. 1955, tel. 599 [Kew, United Kingdom NationalArchives, Public Record Office], PR[im]E Minister's Office Records] 11/1418.4 Report, Templer, 16 Dec. 1955 [Public Record Office], Fforeign] Offfice Records] 371/115658.5 Author, interview, Hazem Nusseibeh, 4 Sept. 2001; Abu Odeh, Hashemite Kingdom, pp. 113-18.

The Crisis in Jordan97Such attempts at compromise were abandoned as Arab politics becamemore polarized during the months leading up to the outbreakof the ArabIsraeli war in June 1967. In a speech on 14 June 1966, Hussein declaredthat 'all hopes have vanished for the possibility of co-operation with thisorganization [the PLO] in its recent form.'1 Possibly the bitterest pillHussein had to swallow after taking his last-minute decision to join theEgyptian-Syrian alliance, was agreeing to Gamal Abdel Nasser's requestthat Shuqayri should join him on the plane home from Cairo. Whateverthe lip service paid to Arab solidarity, the PLO and the Hashemite regimeheld irreconcilable views about authority over the Palestinians living inJordan.*****For Hussein, the most ironic dimension of defeat in the 1967 war was hisrationalization,both at the time and subsequently, of his impetuous decision to join the Egyptian-Syrianalliance in terms of the domestic politicalimplications of standing aside. cAtthat time I had these options: eitherjointhe Arabs or Jordan would have torn itself apart. A clash between Palestinians and Jordanians might have led to Jordan's destruction.'2 Yet thedefeat opened the way forjust such a clash between Palestinians and Jordanians and the most serious challenge to his authorityduring his reign.In the wake of the war, Hussein found himself caught between the Palestinian guerrillagroups, or 'fedayeen', based in Jordan who struck at Israel,and Israel itself, which struck back. The more Israel punished Jordan forthe guerrillas' incursions into either Israel itself, or Israeli-occupied territory, the more it undermined royal authority in Jordan and Hussein'sability to rein in the fedayeen. Both the fedayeen and the Israeliswere thuspartlyresponsible for the crisis of September 1970.In terms of Israeli policy, as Abba Eban argues, the years between 1967and 1973 were the era of the defence minister, Moshe Dayan. Dayan'sthesis of unrelentingstrugglebetween the Arabs and Israelleft little opportunity for accommodation with Hussein. As Dayan put it in an interviewwith Haaretz on 19 January 1968, 'if we are stubborn on all fronts, bothagainstHussein and Nasser, pressure will not decrease I said that there isno way to avert a struggle but it will be easier for us to hold our presentpositions, at least from the viewpoint of Arab psychology.'3 Dayan's1 A. Susser, On Both Banks of the Jordan: A Political Biography of Wasfi al-Tall (London, 1994), pp.100-1; Abu Odeh, Hashemite Kingdom, pp. 125-6.2 Avi Shlaim, interview, King Hussein, 3 Dec. 1996. See also, S. Mutawi, Jordan in the 1967 War(Cambridge, 1987); L. Tal, Politics, the Military, and National Security in Jordan, 1955-67 (Basingstoke, 2002).3 Extracts, interview, Dayan and Haaretz board of directors, 19 Jan. 1968 [PRO], F[oreign and]

98Nigel J. Ashtonannexationist rhetoric in relation to the West Bank left little room for thekind of 'land for peace' settlement that Hussein suggested in secretmeetings with Israelirepresentativesin 1967-8.1Negotiations with Husseinover the West Bank were not the first choice of the Israeli leadership: thedeputy prime minister, Yigal Allon, preferred to work with local Palestinian leaders ratherthan Hussein. Only afternone of them seemed willing toco-operate with Israel did Allon turn to Jordan. In private, Israel's leadersdisparaged Hussein. Allon himself remarkedthat 'today, Hussein is Kingof Jordan, and I don't know who will be in his place tomorrow . I wouldbe happier if it was Shuqayri sitting in Amman today and not Hussein.'2The foreign minister, Eban, explained that 'the Israelis'currentdisillusionment with Hussein derived partly from the too high hopes they had had ofhim before the summer. No one in Israelhad wanted a war withJordan butwhen Hussein threw in his lot with Nasser on 30 May the Israelishad beenshocked. It was also an importantpsychological factor that the Israelis hadsufferedmore casualtieson theJordan front than elsewhere.'3These sentiments match the observations made by informed Westerncommentatorsat the time. Hussein's decision to go to war was regardedasan 'act of treachery. . for which they [the Israelis] will never forgive him'.4According to the British foreign office, Israel saw Hussein as 'expendable'in 1968.5Should peace effortsfail:ManyIsraelis,perhapsthe majority,will tendto comeroundto theviewnow heldby a minorityof 'hawks',that it would be likely to makelife easier, not moredifficultforIsraelif Husseinwerereplacedby an extremistArabnationalistregime. . . The Westernnationswouldbe 'offIsrael'sback',and she wouldneed to takeless accountof world reactionsin determiningthe type and scale of .6In these circumstances, in Dayan's opinion, reprisals against Jordanwere logical, even if they led to the fall of Hussein, because 'if Israel hadnot reacted so sharply to sabotage operations undertaken fromJordanianterritory, the government of Jordan would have reached a modus vivendiwith the terrorists.'7Given Dayan's influence over Israel'sdefence strategy,C [commonwealth] O[ffice Records] 17/550.1 A. Eban, Personal Witness:Israel through My Eyes (New York, 1992), pp. 462-6,496-9. See also USembassy, Amman, to state dept., 30 Dec. 1968, Fforeign] Relations of the] U[nited] S[tates], 1964-8,xx. no. 373.2 R. Pedatzur, 'Coming Back Full Circle: The Palestinian Option in 1967', Middle East Journal, xlix(1995), 273.3 Record of meeting, Brown with Eban, 21 Oct. 1967, PREM 13/1623.4 Hadow to Allen, 25 April 1968, FCO 17/550.5 FCO to UK embassy, Tel Aviv, 26 Feb. 1968, FCO 17/221.6 Hadow to Allen, 25 April 1968, FCO 17/550.7 M. Dayan, The Story of My Life (London, 1976), pp. 351-3.

The Crisis in Jordan99there is little wonder that, despite Hussein's efforts, there was no diminution in the pressure exerted by the Israelijaw of the militarynutcrackerinwhich he now found himself.*****The increasingassertivenessof the fedayeen groups based in Jordan meantthat the pressure exerted by the otherjaw of the nutcrackeronly increased.Hussein's problem was crystallized by the battle of Karamehon 21 March1968, which marked a turning point for both the fedayeen and the Hashemite regime. Here, in retaliation for the bombing of a bus carryingschoolchildren through the Negev Desert by Yasser Arafat'sFatah group,the Israelis decided to raid the refugee camp that also acted as Arafat'sheadquarters,at the village of Karamehin the Jordan Valley. They ignoredHussein's attempt to forestall retaliation by sending a secret message, byway of the US state department, in which he expressed deep regret at thebombing and asked for any informationthat would help him to trackdownthe perpetrators.1At Karameh, the Israeli forces met stiff resistance fromthe Jordanian army and Arafat's fedayeen. Jordanian artillery wrecked anumber of Israeli tanks, while the fedayeen stood their ground and foughtbravely.When the Israeliswithdrew afterpartly demolishing Karameh,thetanks they left behind were later paraded through Amman as symbols ofvictory.2More important than the battle itself, however, was the propagandavictory won by Arafat and the fedayeen. Karameh became a symbol ofPalestiniannationalpride, and spurred the development of the Palestiniannational movement.3Arafat burnished his own image with stories of hiscommand of the resistance and heroic escape by motorcycle.4 Mostobservers, including the British ambassadorat Tel Aviv, Michael Hadow,argued that the attack had backfiredon the Israelis, for it not only dentedthe image of Israel'smilitaryinvincibility, but also turned the fedayeen intopopular heroes in Jordan.5 Israel's permanent representativeat the UnitedNations, Gideon Rafael, later acknowledged that cthe operation gave anenormous uplift to Yasser Arafat's Fatah organization and irrevocablyimplanted the Palestine problem on to the international agenda.'6At the1 UK embassy, Tel Aviv, to FCO, 19 March 1968, FCO 17/625.2 See Weston-Simons, 'Report on Operations in Karama YA 4539 and SAFI YV 3535 Areas on 21March 1968', 24 March 1968, FCO 17/633.3 See W. A. Terrill, 'The Political Mythology of the Battle of Karameh',Middle East Journal, lv (2001),91-111.4 Ibid., p. 100.5 Hadow to Stewart, 'The KaramaRaid', 1 Apnl 1968, FCO 17/6336 G. Rafael, Destination Peace: Three Decades of Israeli Foreign Policy: A Personal Memoir (New York,

iooNigel J. Ashtonfifth meeting of the Palestine National Council, in Cairo in February1969,Arafatwas elected chairmanof the PLO's executive committee. As AdnanAbu Odeh writes, 'to Fatah, al-Karamawas a vindication of its strategy, asource of Palestinianpride, and a solid credential for soliciting Palestinianand Arab support.'1The Jordanianarmy, which saw itself as the victor of Karameh,resentedthe fedayeen's appropriationof the glory. The battle markedthe parting ofthe ways between the army and the guerrillas. Hazem al-Nusseibeh, at thetime minister of reconstruction and economic development, later arguedthat had the PLO been willing to acknowledge the army'srole at Karameh,the crisis of September 1970 might have been forestalled. Karameh, heargued, 'could have been the foundation of closer relations rather than ofdivision'.2The PLO's strategy placed Hussein in a dilemma. As he could neitherignore the groundswell of popular support for the fedayeen, nor afford toalienatethe army,whose loyalty was the guarantorof his throne, he tried tostraddle and, if possible, close the divide between them. In particular,hestressed that Palestinians and Jordanians were united in the struggleagainst Israel. Only the 'steadfastness' (al-sumud) of all could bring victory.3This sentiment underlay his oft-quoted comment two days after thebattle of Karameh:'I think we have come to the point now where we are allfedayeen.'4Hussein's attempt to build a common front failed. Under the weight ofIsraeli attacks, the fedayeen were driven back during 1969 from theirforwardbases in the Jordan Valley to the main East Bank towns and cities,in particularAmman. Here they acted as a state within a state, ignoring theauthority of the local police and antagonizing the army. By the beginningof 1970, Hussein's pleas for steadfastness and unity were redundant.Instead, on 10 February, the government issued twelve decrees requiringthe fedayeen to obey the law of the land.5The decrees provoked such hugedemonstrations in Amman that, the following day, Hussein instructed thegovernmentto suspend them.The next display of the evaporationof royal authorityfollowed in April.The Richard M. Nixon administrationcancelled at short notice a visit to1981), pp. 202-3.1 Abu Odeh, Hashemite Kingdom, p. 172.2 Author, interview, Hazem Nusseibeh, 4 Sept. 2001.3 Abu Odeh, Hashemite Kingdom, p. 173.4 S. A. El-Edross, The Hashemite Arab Army, 1908-79 (Amman, 1980), p. 442.5 According to Yigal Allon, the Israeli government signalled to the king at this juncture that if hewanted to bring troops into Amman to deal with the 'terrorists', 'they would not take advantage of thesituation': meeting, Heath with Allon, 26 Feb. 1970, PREM 13/3331. See also Y. Sayigh, Armed Struggleand the Searchfor State: The Palestinian National Movement, 1949-93 (Oxford, 1997), pp. 246-7.

The Crisis in Jordan101Amman by the US assistant secretaryof state,Joseph Sisco, in the face ofstreet demonstrations mounted by the fedayeen and their supporters.Hussein, who took the decision as a personal insult, implying that his writno longer ran in Amman, blamed it on the US ambassador, HarrisonSymmes, whose recall he now formallydemanded.1In fact, the Sisco affairwas the last in a succession of incidents that had eroded Hussein's confidence in Symmes.2 The request for the ambassador's removal in themidst of such a crisis said much about Hussein's strainedrelationswith theUnited States, which he blamed for indirectly encouraging Israeli aggression againstJordan through the supply of arms.3* * * * *The Sisco affairalso led the governmentsof Syriaand Iraq to reassess theirestimates of the probability of Hussein's political survival. An Iraqi delegation to Amman in May 1970 promised Arafatsupport should he mount acoup against the Hashemite regime.4As Iraqi troops had been stationed inJordan since 1967, their intentions remained an imponderable for Husseinand his advisers throughout the crisis. A threat from Iraq - in the wake ofan attempt on 1 September1970 by the Popular Front for the LiberationofPalestine (PFLP) to assassinateHussein - to the effect that unless the armystopped firing on the fedayeen, Iraq's Eastern Command would intervene,led Hussein to call for ajoint four-powerstatementfrom the United States,Britain, France, and the Soviet Union condemning Iraq.5Likewise, in thewake of Syria's attack on the 19th, the movement of the Iraqi troops inJordan caused alarm,although no clash with theJordanianarmy.6The possibility of Iraqi or Syrian intervention showed that Husseincould not afford to neglect the broader Arab context in seeking a way outof his dilemma. After the 1967 war, Hussein had had some success in improving relationswith Nasser, who felt partly responsible for the problemsHussein faced as the result of placing his forces under united Arabcommand. Unlike the Syrian or Iraqileadership, Nasser and Hussein wereprepared to accept United Nations Security Council Resolution 242 of 22November 1967, which called for the return of occupied territory in1 End. in US embassy, Amman, to state dept., 16 April 1970 [Washington, DC, United States NationalArchives and Records Administration], R[ichard M.] N[ixon] Presidential] P[apers, Middle East,Country Files, National Security Council Files], box 614, folder Jordan IV.2 Author's confidential interview source.3 US embassy, Amman, to state dept., 28 Feb. 1970, RNPP, box 614, folder Jordan III.4 Abu Odeh, Hashemite Kingdom, pp. 175-6.5 UK embassy, Amman, to FCO, 2 Sept. 1970, PREM 15/123;Kissinger, WhiteHouse Years, pp. 598-9.6 Each regime tried to use the other's failure to protect the fedayeen as a propaganda tool in the wake ofthe crisis: E. Kienle, Ba'th versus Ba'th: The Conflict betweenSyria and Iraq, 1968-89 (London, 1990),P-53-

102Nigel J. Ashtonexchange for peace.1 Unfortunately for Hussein, Nasser's sympathy didnot translateinto support for measures to extirpate the fedayeen threat tothe throne. Nasser hoped to retainan influence over the PLO by bolsteringArafat'sFatahmovement within it.*****The final question in Hussein's mind by the summer of 1970 concernedthe intentions of the fedayeen themselves. Had his calls for unity failedbecause the fedayeen aimed to topple the Hashemite regime, or becausethey took a differentview of the strategyto be adopted in the strugglewithIsrael?Within the PLO, Arafat'sFatah faction took a more moderate ideological line than George Habash's PFLP and Nawaf Hawatmeh's PopularDemocratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PDFLP), which wereideologically committed to the downfall of the Hashemite monarchy.Although the PFLP sponsored the attempts on Hussein's life in June andSeptember, Fatah, with its Palestinian nationalist mission and supporterswithin the army and security services, presented the greater threat.2Hussein's doubts whether Arafatcould be trusted to control the so-called 'synthetic' groups partly explain his decision to opt for the use of militaryforcein September.3Whether or not Arafatplanned to move against Hussein in September1970 is unclear. Although his deputy, Abu Iyad, later insisted that the lastthing Fatah wanted was to take over authority in Amman, Mudar Badran,who, until 2 August 1970, was head of Jordan's General Intelligence Service, and who subsequently became prime minister, insists that a PLOrepresentativein Riyadh told him in 1973 of a Fatah-backedplan to moveagainst Hussein on 19 September, two days after Hussein had decided totake action.4 By then, it was clear to both sides that the status quo couldnot hold. Either the Hashemite regime or the PLO had to take theinitiative.The series of spectacular terrorist acts carried out by the PFLP forcedHussein's hand. By the end of August 1970, the fedayeen movement inJordan had reached a crossroads. The success of the United States inbrokering a ceasefire in the Egyptian-Israeliwar of attrition at the end ofJuly seemed to bring Nasser and Hussein closer together in pursuit of a1 Nasser confirmed in private that he had told King Hussein he could make a separate settlement withthe Israelis if he wished, but that Egypt could only do so if Israel gave up all of its 1967 conquestsincluding Jerusalem (UK embassy, Cairo, to FCO, 9 Dec. 1968, PREM 13/2775).2 Sayigh, Armed Struggle, pp. 244-5.3 Abu Odeh, Hashemite Kingdom, pp. 178-80.4 Author, interview, Mudar Badran, 20 May 2001; Abu Odeh, Hashemite Kingdom, p. 180. See also,Sayigh, Armed Struggle, pp. 254-5.

The Crisis in Jordan103settlement with Israel.1At an emergency session of the Palestine NationalCouncil in Amman at the end of the month, the radicals called for theoverthrow of the Hashemite monarchy. Although Fatah did not endorsethe call, the moderates were undercut by the PFLP's hijacking of threecivilian airliners on 6 September. Two of them were flown to Dawson'sField, near Zerqa, and the third to Cairo. On 9 September, a fourth planewas hijacked and flown to Dawson's Field. The PFLP were left holdingfive hundred hostages, including US and British nationals. There couldhave been no clearerdemonstrationof Hussein's impotence.The hostage saga provided one of the subplots in the September showdown. While the PFLP released all of the women and children beforedestroying the aircraft, they held on to fifty-four of the male hostages,including the Britons and the US-Israeli dual nationals. In exchange for thelatter, they demanded the release of an unspecified number of Palestiniansheld in Israelijails. This caused friction between Britain and the UnitedStates; the formerwilling to be flexible in trying to satisfy PFLP demands,while the latter took a tough line.2 Nonetheless, owing to the isolation ofthe US embassy in Amman, the new US ambassador, Dean Brown, persuaded the state departmentto designate the British ambassador, SirJohnPhillips, as thejoint collector of information.3Britain's communications played an important role in the crisis. Theonly secure scramblerline to which Hussein had access had been installedby MI6's agent in Amman, Bill Speirs.4 Its existence has been confirmedby a key CIA source, by the chief of the royal court, Zeid Rifai, and byKissinger.5Speirs, who had gained Hussein's confidence, also had a goodworking relationshipwith his CIA counterpart,Jack O'Connell. The valueof the line was emphasized by Brown's experience. Several times, whentrying to telephone Hussein, he found the fedayeen had intercepted hiscall. He reported that on one occasion they had answered him with the1 W. B. Quandt,PeaceProcess:AmericanDiplomacyand theArab-IsraeliConflictsince1967(Washington, DC, 2001),p. 76.2 Cf. E. ife (London,1998),pp. 322-3.3 US embassy,Amman,to statedept., no. 4997, 21Sept. 1970,RNPP,box 615,folderJordanV; statedept.to US embassy,Amman,no. 155208,22Sept.1970,ibid.4 Author,interview,Zeid Rifai,5 June 2002. The BritishDiplomaticServiceList shows ''WilliamJamesMcLarenSpeirs(born 22 Nov. 1924)'as havingservedas firstsecretaryat the embassyin TelAvivbetweenJune 1970andJuly 1972.His presencein Ammanduringthe crisisis confirmedcircumstantiallyby a letterin the foreignofficefiles fromthe producerof the thankinghim for his help in settingup a televisioninterviewwith KingHussein(FCOto UKembassy,Amman,tel. 418,28 Sept. 1970,FCO 17/1084).His roleas MI6'smanin Ammanhas been confirmedto me in privatecorrespondenceb

Dec 03, 2013 · Pulling the Strings: King Hussein's Role during the Crisis of 1970 in Jordan Author(s): Nigel J. Ashton . It leaves little room for Hussein's own initiative, even though Kissinger still expresses a healthy respect for Hus- sein's political skills.