Transcription

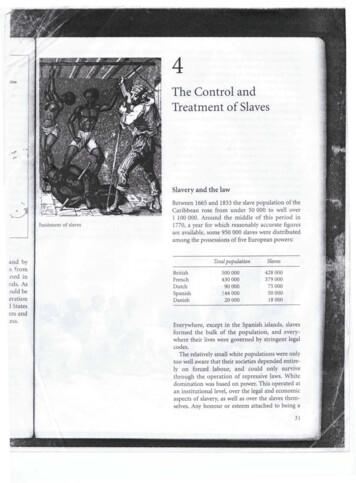

4illesThe Control andTreatment of SlavesSlavery and the lawPunishment of slavesand byn from:ned innds. AsDuld beerationi Statesnts and:ess.Between 1665 and 1833 the slave population of theCaribbean rose from under 50 000 to well over1 100 000. Around the middle of this period in1770, a year for which reasonably accurate figuresare available, some 950 000 slaves were distributedamong the possessions of five European powers:BritishFrenchDutchSpanishDanishTotal populationSlaves500 000430 00090000144 00020000428 000379 000750005000018000Everywhere, except in the Spanish islands, slavesformed the bulk of the population, and everywhere their lives were governed by stringent legalcodes.The relatively small white populations were onlytoo well aware that their societies depended entirely on forced labour, and could only survivethrough the operation of repressive laws. Whitedomination was based on power. This operated atan institutional level, over the legal and economicaspects of slavery, as well as over the slaves themselves. Any honour or esteem attached to being a31

slave-owner arose only from the power that hecould exercise over the bodies of his slaves, and thishad to be sanctioned by slave laws. Such lawsmeant that white men and women could exerciseintimate power through punishment, torture andcontrol of all a slave's physical needs. In drawingup and enforcing such laws the slave-owners in theCaribbean, like those in the rest of the New World,created their own version of slavery. They inventedfrom scratch all the ideological and legal underpinnings of a totally new slave system.In the eighteenth century about 90 per cent ofall slaves worked. Only the invalids, very youngchildren and the infirm, who made up the other10 per cent were exempt. The vast majority workedon plantations. There, when they were not havingto carry out hard manual labour, they were subjected to, or threatened with, flogging and mutilation for a wide and constantly increasing variety ofoffences. Slave women were abused by white men,and all - men, women and children - were more orless abandoned to under-nourishment and disease.The non-plantation slaves, the logwood cutters inCentral America, and those in places like theBahamas, the Cayman Islands, Anguilla, Barbudaand the Grenadines, had slightly better lives butInspecting slaves32were still subject to very similar slave codes. Thosecodes ran very much to a pattern, regardless of thenationality of those who operated them, but thoseenforced in the British islands were undoubtedlythe most severe.Slave laws and codes in the BritishCaribbeanAlthough slavery was not a condition recognisedunder English law there was little or no oppositionin England before the 1780s, to either the slavetrade or the institution of slavery in the Caribbeancolonies. As a result, the life of a slave in such acolony was dominated by laws drawn up by thelocal Assembly, most of whose members wereslave-owners. These were men concerned primarilywith the protection of property and the control ofan unwilling workforce, fully aware that such asystem could not survive without a repressive legalcode.To such men, slaves were chattels, private possessions like animals or furniture acquired by purchase or inheritance. As a fundamental principle ofEnglish law was the security of property, allowingan owner to do what he liked with his possessions,this t« -wnelust iIt man;existworemento tleithgrianstaterigicwanSithe :combothrighaim1thei bruEadmarma whicopandin tclai.andeithTevesdorfrojAmthe

this took the slave out of the law's jurisdiction. Theowner of a chair could destroy it if he wanted to,just as he could slaughter a cow he might possess.It therefore followed that how he treated his slaveswas entirely his own affair. Slaves were privateproperty and, like animals, could be sold to meetdebts or disposed of in accordance with the laws ofinheritance of real estate. This definition of slavesunder British West Indian law denied them anyprotection under English law. Slave-owners weregiven wide discretion in enforcing control, anduntil late in the eighteenth century the slave codesallowed them to do very much as they liked withregard to every aspect of their slaves' lives. Amongmany other things, the law ignored completely theexistence of family ties, gave no protection towomen against overwork, sexual abuse, or ill treatment during pregnancy, and laid down no limitsto the punishments that could be inflicted oneither males or females. In the words of one historian of slave society, 'The slave laws legitimized astate of war between blacks and whites, sanctifiedrigid segregation, and institutionalized an earlywarning system against slave revolts.'Such laws began to be passed in the middle ofthe seventeenth century. By 1661 Barbados had acomprehensive slave code. Although this accordedboth masters and slaves carefully differentiatedrights and obligations, it left the masters withalmost total authority over the life and death oftheir slaves. The code saw slaves as 'heathenish' and'brutish', and unfit to be governed by English law.Each slave-owner was required to act as a policeman, to suppress any humanitarian feelings hemay have had, and to deal with his slaves with awhip constantly to hand. The Barbados code wascopied by the Jamaican Assembly three years later,and later formed the basis of all the others enactedin the British Caribbean. Punitive and coerciveclauses formed a major part of all the slave codes,and very little attention was paid to the welfare ofeither men or women.The effect of the laws was to deprive the slaves ofeven the smallest and most inconsequential of freedoms, and at the same time to restrict their ownersfrom granting even the slightest concession.Among the most important common features ofthe slave codes were laws designed to prohibit andOwners with new acquisitionssuppress unauthorised movement and the congregation of large numbers. Slaves were also bannedfrom possessing weapons, horses and mules, fromsounding horns or beating drums, and from thepractice of secret rituals. Special slave-trial courtscould dispense summary 'justice', but slave-ownerswere given very wide discretion in punishing theirslaves. The courts usually dealt with slaves whowere recaptured after running away, or who wereaccused of crimes such as theft. Punishment foractual or threatened violence against any whiteperson was very severe.Although the various slave codes ran to apattern, they all contained individual provisionsreflecting the condition of the society in whichthey were drawn up. In the Bahamas slaves couldbe flogged for selling such things as liquor, eggs,fruit or vegetables, or if found gambling. InBermuda they were not allowed to wear brightclothes or ornaments, nor even to carry a stickunless .they were decrepit or lame. A MontserratAct of 1693 permitted any white man to kill a slavewho was caught stealing provisions, and if a slavestole anything of value he or she was liable to beflogged and have both ears cut off. Under an Actpassed in the Virgin Islands in 1783, if a slave33

struck or opposed any white person the punishment was not only flogging but having the nose slitand 'any member cut off. Such provisions formutilation were commonplace. The penal codedeveloped in Jamaica was the most savage of themall, and attempts to modify it were constantlythwarted by the power of the planters in thelegislature.cut into four pieces. Or he could simply be burntto death, which in Jamaica in 1740 was laid downas the punishment that a slave would incur forstriking a white person. All of these methods ofcapital punishment were in use in Europe duringthe seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but notas a punishment for such minor crimes as runningaway from work, or for hitting another person.PunishmentsManumissionThe punishments dealt out both by the courts andby individual slave-owners were very severe. Theiraim was to deter and humiliate, not to 'make thepunishment fit the crime'. The way that ownersruled their slaves varied from owner to owner, andfrom one society to the next, but there werecommon features. The most important and mostcommon form of punishment was flogging, andpersonal coercion using the whip must be seen asthe denning characteristic of slavery. On any plantation, floggings were totally unchecked by anyoutside authority. Brutality and sadism could befound anywhere. Severe floggings were oftenaccompanied by some form of mutilation. Lesssevere whippings and beatings were frequentlycarried out in conjunction with making thosebeing punished commit humiliating or disgustingacts. For urban slaves not only the whip, but structures such as the stocks and the pillory which werefound in every town, were ever-present remindersof what awaited those who failed to work hard orshow proper respect.The death penalty was awarded for what wouldnow be considered relatively minor offences. Anextreme example of this was a Barbados law of1688, which made the theft of items worth morethan 12 pence punishable by death. The penaltywas carried out in a number of barbarous ways, alldesigned to prolong the agony involved as long aspossible, and to present other slaves with theclearest demonstration of the power their ownersheld over their lives. A slave could be hanged, orbeaten to death while lashed to a cart-wheel, or hecould be hung up in an iron cage until he diedfrom hunger and thirst. Alternatively he could behanged until he was near to death, and thenrevived in order to be disembowelled before beingWhether a slave could be given his freedom or notwas entirely dependent on his owner. The manumission laws were more stringent than in theFrench or Spanish possessions, and owners werereluctant to give freedom, as a large sum had to bedeposited at the local vestry to ensure the newlyfreed man or woman did not become a burden onthe parish. A figure similar to that of the 100which was required in St Vincent in 1767 wascommon. In Jamaica, by a law passed in 1717,manumitted slaves were required not only to carrywritten proof of their freedom, a precious document which all the newly freed needed, but to wearan identification badge. The manumission of slavestoo old and feeble to work was illegal, but it didtake place, and was one reason why the vestrydeposits were required. By law, owners wererequired to maintain their slaves when too old towork.It was only in the manumission content of slavelaw that female slaves were in a more favourableposition than males. This came about because ofthe unions formed with white men. A slave womanwho had had a long-standing relationship withsuch a man sometimes benefited under his will bybeing given her freedom, but more usually it wasthe children of such a union who were freed. Thenumber of women who gained their freedom inthis way was small, and very much restricted to'those who had had particularly privileged household positions, or who were themselves lightskinned mulattoes. As the eighteenth centuryprogressed, more such women, regardless of thecolour of their skin, received manumission orbequests, as did their children. This so upset whitesociety in Jamaica that in 1762 a law was passed toprevent sums of more than 2000 being left to34

mulatto children. All in all, until well into thenineteenth century, women were twice as likely tobe manumitted as men were.Marriage and divorceAlthough there was no legal form of marriage forslaves before 1789 this does not mean that marriages did not take place before that date. From theearliest days of slavery, marital and family linkswere valued by the slaves. This was recognised bythe planters, who soon saw that if the plantationswere to be run efficiently they needed to buywomen in proportion to men. The slave marriageswhich then took place, using the form of ceremonyor agreement brought with them from Africa, didnot correspond to anything with which theplanters were familiar. Marriage in Europe wasvery much concerned with the transfer of wealthand property, and in European society divorce wasvery rare. Among Africans it was no more thancommon sense to end an unsatisfactory relationship with a simple divorce rite such as that whichcame to be used by the slaves in Jamaica. Thisinvolved the cutting in half of a cotta, the pad usedfor carrying head loads, as a symbol of the severance of mutual affection. Such a rite also reflectedon the independence, autonomy and relativeequality of African women with men - all of whichwere missing from white society. Unfortunately,because slaves did not marry in church, anddivorce was so uncommon in European society, thewhites considered slave unions to be immoral aswell as shallow and unstable.ReligionUnlike the Catholic clergy in the Spanish andFrench Caribbean who were officially committedto converting slaves to Christianity from the beginning, the Anglican Church took no interest in theslaves of the British Caribbean until the finaldecades of slavery. In the early days some slaves inJamaica, Barbados and one or two of the LeewardIslands came into contact with Christianity eitherthrough working alongside Catholic servants, or as. a result of the activities of Quakers. The attemptsby Quakers in these islands to convert slaves metwith great hostility from the slave-owners, andtheir meeting-houses were all closed down longbefore the end of the seventeenth century. Afterthat no interest was taken by anyone in the spiritual welfare of the slaves until around the middle ofthe next century.All non-Christian beliefs and practices were outlawed under the slave codes, but the slaves wereable to adapt and disguise the ways they worshipped. Many of the dances and ceremonieswhich the whites thought their slaves took part inmerely to amuse themselves often had considerablereligious significance.Christianity was brought to the slaves in theeighteenth century, first of all by lay people, bothblack and white. These ranged from the odd piousplanter or white artisan to free blacks who had allin some way been inspired by a religious revival inBritain. The first full-time missionaries, belongingto the Moravian Church, arrived in Jamaica in1 754 and the Leeward Islands two years later. Theywere soon followed by the Methodists and Baptists.All had to establish a right to preach to the slaves inthe face of enormous hostility. This they eventuallydid, but mainly through preaching that obedienceand docility were prime virtues, and that all earthlyefforts needed to be directed towards achieving animmortal afterlife.By the beginning of the nineteenth centuryperhaps 25 per cent of all slaves had been converted. This then stirred the Anglican Church intosome sort of action. This was not very great, as theChurch considered the slaves had no morals. In theeyes of the Anglican clergy the fact that many slavecouples lived together and produced children,without having been married in a church by apriest, made them fornicators who were unworthyof much consideration. Taking into account thenumbers who had already joined theNonconformist Churches, this left the AnglicanChurch with only a limited number of slaves theycould make any real effort to convert.EducationOther tnan being taught how to carry out thelabour- required of them, slaves were deniedany education whatsoever. The vast majority of35

slave-owners were opposed to any suggestion thattheir slaves might be taught to read and write. Itwas not until the first missionaries arrived in theCaribbean in the middle of the eighteenth centurythat slaves received instruction in anything otherthan how to work.It took a long time for the missionaries to overcome the opposition of the slave-owners to theirinstructing slaves in the doctrines of Christianity.By the time they had been generally accepted, Biblereading, which had become a widespread habit inBritain due to a religious revival, formed animportant aspect of missionary activity. This led tothe missionaries becoming involved, to the dismayof slave-owners, in teaching slaves how to read.Where laws did not already exist forbidding theteaching of slaves to read and write, they were soonpassed, as happened in Barbados in 1797. An Actpassed that year made it the duty of every Anglicanpriest to try to convert the slaves, but made itillegal to teach them reading and writing. InDemerara twenty years later the Reverend JohnSmith of the London Missionary Society waswarned by the Governor of the colony that hewould be banished if he attempted to teach anyslave to read.In spite of such laws, some slaves did manage tobecome literate, or at least able to read, and probably more women than men. This was because ofthe intimate relationships some female slaves hadwith white men, and because more women thanmen were employed as domestics in situationswhere the opportunities to learn were greater. Onesuch was Nanny Grig, a slave on an estate inBarbados who, because she could read, was partlyresponsible for starting an insurrection there in1816 (see Chapter 5). However, right up until theend of slavery, there was no official attempt anywhere to give the slaves even the most elementaryeducation.Forces of law and orderWith slaves forming the bulk of the population, theslave-owners everywhere lived in fear of an uprising or revolt, and security was a prime concern.This was provided in a number of ways.36All able-bodied white males were required toenrol in the Militia, and turn out regularly for thedrills and parades which were intended to preparethem for military duties. The various Militia lawsand regulations were rarely observed in full. Themore prominent citizens usually refused to serveexcept as officers, and the planters resented allowing their white employees time off to train. In mostislands this resulted in a Militia which was topheavy with captains and colonels, grossly undermanned and poorly trained. As time went by, insome islands coloureds and even free blacks werebrought into the Militia, but only to make upnumbers and to do the most humdrum tasks.Garrisons of regular British troops began to bestationed in Jamaica, Barbados and the LeewardIslands from late in the seventeenth century. Theseprovided the slave-owning communities withadded reassurance. That they must also have actedas a deterrent to any slave uprising was demonstrated in Barbados in 1692 and in Antigua in1736, where conspiracies took place as soon astheir garrisons were withdrawn. British troopsplayed an active part in putting down the insurrection in Barbados in 1816.In addition to the regular troops and militiamenproviding security from both internal and externalthreats, the whites also depended on constables tohelp exercise control over the slaves, particularlythose who lived in the towns. Urban slaves wereemployed in less restricted ways than those on theplantations, and had more freedom of movement.They worked not only as domestics, artisans,boatmen and fishermen, but in a wide range ofother occupations connected with the retail anddistributive trades. As such they moved around agreat deal, and were generally far less amenable todiscipline from their owners than plantationworkers. Constables were appointed to providegreater control. These patrolled the streets, checking on the slaves' activities, and at night enforced acurfew system. Later in the eighteenth centuryplaces of correction, called workhouses, wereestablished in the main towns. In these, urbanslaves caught breaking any of the numerous laws ?which bound their lives could be detained andpunished. The constables also acted as freelanceslave whippers, who would flog any slave for a fee.

They were called 'Jumpers' in Barbados. Theirservices were often used by owners who did notwant their errant slaves sent to the workhouse.Other forms of slave controlThroughout the colonies unwritten laws broughtabout patterns of behaviour which made the slaveowners' control over their slaves even stronger.Everywhere custom was just as important as thelaw in shaping the lives of the slaves. The determined efforts of the whites to make blacks feelracially inferior served to strengthen their domination, It was instilled into slaves that all whitepeople, no matter how lowly or uncouth, wereabove non-whites everywhere, and as time went bythe division of society by colour became more andmore pronounced.Slaves were denied any recognition or symbol ofachievement, and a black skin was automaticallyequated with slavery and social inferiority. Africanculture was always described as being inferior,while African customs were ridiculed and suppressed. At the same time European values,systems and culture were presented as being superior. Constant efforts were made to undermine theblacks' self-worth and to foster dependence onwhites.Even Christianity was used to promote blacksubmissiveness, and to try to persuade slaves thattheir condition was ordained as part of the naturalway of life for black people. The Scriptures werecensored and interpreted to this end, and religiousinstruction was designed to encourage meeknessand acceptance. Slaves were taught that God wasopposed to insolence and bad behaviour, and thatslavery was a divine punishment for past conduct.free blacks they also included Maroon bands andAmerindians.The nature of the relationship between thewhites and these groups depended very much onhow heavily the whites were outnumbered by theslaves. In the middle of the eighteenth century inJamaica, where the ratio was ten to one, thecoloureds were granted significant civil rights inreturn for their loyalty, and independent Marooncommunities (see Chapter 5) were allowed toremain in existence in return for their help inhunting down runaway slaves. Where the ratio ofblacks to whites was not so uneven, as in Barbadoswhere it was about four to one, such liberalrelations were not considered essential. This didnot prevent the free coloured community fromgiving the Barbados whites their full support intimes of emergency such as, for instance, in 1816when coloured militiamen were conspicuous inhelping to put down the slave insurrection of thatyear.Free blacks, if not so welcome as militiamen,were used as slave-hunters and constables. Manyhad to take these jobs because they were unable tofind any other employment, and such work offeredthe only alternative to starvation. Early in the eighteenth century Amerindian trackers from theMoskito Coast of Central America were used tohunt down runaway slaves in Jamaica. Towards theend of the same century South AmericanAmerindians were used in the same way in theGuianas. The use of the free blacks andAmerindians in this way was by no means intended to give either group additional status or anentry into the world of the whites. Rather it can beseen both as a means of getting unpleasant jobsdone on the cheap, and of discouraging nonwhites from seeking a common cause under whichthey could unite against the whites.Pro-slavery alliancesIn places where they were greatly outnumbered,the whites found it expedient to enter into allianceswith free non-white groups in order to increasetheir control over the slaves. These were the socialgroups who stood to benefit from the continuedexistence of a subservient and well-controlled slavecommunity. As well as the free coloureds and theAmeliorationThe slave codes were all revised many times, withchanges in the law only taking place in response toeconomic conditions and outside pressures. Allsuch changes only made the life of the slaves worse.It was nearly the end of the eighteenth century37

before the distress caused by the constant mutilation and murder of fellow human beings compelled the local legislatures reluctantly to pass Actsrestraining the powers of slave-owners, and tomake the murder of a slave a capital offence. At thesame time ameliorative laws, designed to better thegeneral condition of the slaves, were introduced.All came about because of the growing threat,as the planters saw it, of abolition of the slavetrade, accompanied by uncertain economic conditions and a price rise in slaves brought aboutby war.From the 1780s onwards individual coloniesamended their laws to improve the material existence of slaves, to reduce mortality, and to promotea healthy natural increase among them. Many ofthe new laws were intended to protect pregnantwomen, encourage motherhood and promotestable unions by offering cash incentives to slaveparents. Fines were also laid down for whites who'interfered' with married female slaves.Other reforming laws followed. In 1787 Antiguapassed an Act which allowed slaves the right to trialby jury in serious cases. The 1792 ConsolidatedSlave Act of Jamaica imposed a fine of 100 foranyone found guilty of mutilating or dismembering a slave. Four years later the legislature of theBahamas passed laws which regulated theminimum amount of food and clothing which hadto be given to the slaves, laid down the maximumamount of punishment which could be inflicted,and gave them the right to marry. In 1798 a similarSlave Amelioration Act was passed in the LeewardIslands. The Barbados legislature delayed evenlonger in passing such an Act, and a law which laiddown a fine of 15 for the murder of a slave wasnot repealed until 1805.The Amelioration Laws, although widely welcomed by the slaves, in the end made their livesonly marginally better. The strict enforcement ofthe slave laws was considered essential to theefficient running of a plantation economy, andowners continued to exercise absolute control overtheir human property until the very last years ofslavery. Although owners no longer legally had thepower of life and death over their slaves, manyconsidered this an unfair interference with property rights. They could not accept that killing a slave38had become a capital offence, and it was still possible to get away with murder.In 1810 a planter in Nevis named EdwardHuggins marched twenty of his slaves to themarket-place in Charlestown, and had themflogged by two freelance whippers in the presenceof his two sons. One slave received 365 lashes, andanother 292 lashes. One female died and severalother slaves were badly mutilated. Huggins wasbrought to trial, but as fellow planters made up thejury he was acquitted. Five magistrates who hadbeen present during the flogging were deprived oftheir offices. The case caused such an uproar, bothin the West Indies and in Britain, that when in1811 a planter in Tortola was accused of murderinga slave, the Governor-in-Chief of the LeewardIslands stepped in to see justice done. The planter,Arthur Hodge, was notorious for the ill treatmentof his slaves, and had probably caused severaldeaths. He was tried in the presence of theGovernor, Hugh Elliot, for one particularly gruesome murder. The jury, made up of his fellowplanters, reluctantly and after twelve hours ofdeliberation found him guilty, but recommendedhim to Elliot for mercy. The Governor refused,proclaimed martial law, and ordered Hodge to beexecuted. He was hanged a few days later, becoming the first West Indian slave-owner to lose his lifefor having taken that of a slave.Slave codes in the non-British CaribbeanThe European perception of blacks as an inferiorrace can be seen in all the slave codes used in theCaribbean, regardless of how and where they weredrawn up. However, there were important differences, both in their content and structure, and inthe way they were conceived. The Spanish andFrench codes, unlike those of the British, weredrawn up and enacted in Europe and were similarto each other. Both tried to disguise racism and theexploitation of slaves by concentrating on paternalism, and by suggesting that if the slaves wereobedient and accepted their condition thissomehow legitimised the slave-owners' rights.Each attempted to balance the need for repressionwith protection, and made it plain that the owners Iwere entitled to exploit their slaves in return for

11 possi-guarding, instructing and guiding them. TheDutch and Danish slave codes resembled theFrench more than either the British or Spanish, butboth concentrated on suppression rather than protection of the slaves.The Spanish CodeThe Spanish had a slave code for their Europeanterritories before they acquired possessions in theNew World and they simply transferred this codeto the Indies. It was drawn up in the thirteenthcentury and was called Las Siete Partidas.The basic difference between the Spanish slavecode and other slave laws was that the Spanishacknowledged that slavery was contrary to naturaljustice and that it was an evil, but a necessary evilfor the economic development of the colonies.This admission caused endless trouble in theSpanish colonies, as it implied that freedom wasthe natural state of man and gave the slaves theirjustification for revolting. The first slave revolt wasrecorded in Hispaniola as early as 1522, and thereafter there was a steady stream of revolts in Spanishterritories. The authorities recognised the right ofslaves to seek their freedom, so they tried toremove the danger of revolt by other means thanrepressive legislation.Charles I attempted to enforce a ratio of three toone or four to one of slaves to freemen. He alsotried to enforce a minimum proportion of femaleslaves and, by encouraging marriage, to create asettled family life for the slaves and make them lessinclined to revolt. The Spanish slave laws promoted more humane treatment for slaves and led to afar larger proportion of free blacks and mulattoes.For example, in Puerto Rico by the end of theeighteenth century free coloureds outnumberedslaves, and in Cuba they were nearly equal innumbers.A slave could appeal to the courts against illtreatment. He could purchase his freedom withoutthe consent of his owner merely by repaying hispurchase price, if necessary by periodic repayments. The slave had a right to his provisionground with the consent of his owner. He hadthe right to marriage without the con

Spanish Danish 500 000 430 000 90000 144 000 20000 428 000 379 000 75000 50000 18000 Everywhere, except in the Spanish islands, slaves . giver until allow regar man; exist wore men to tl eithg rian state rigic wan Si the : com both righ aim1 thei bru Ead mar ma>