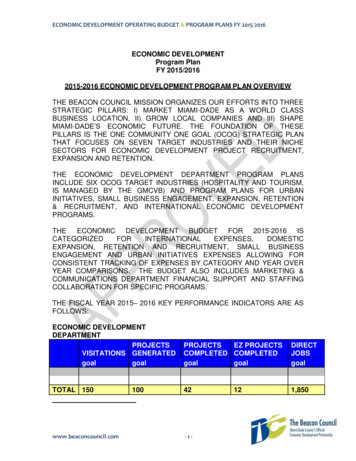

Transcription

The BloomsburyIntroduction toCreative WritingInstructor’s ManualPrepared by the author of The BloomsburyIntroduction to Creative Writing,Dr Tara Mokhtari9781472578440 txt online.indd 103/10/2014 14:36

Contents1. Introduction 12. Chapter by Chapter Notes and Reading Lists 33. Bonus Exercises or Assessment Tasks 84. Glossary 135. Online Media 199781472578440 txt online.indd 203/10/2014 14:36

1. IntroductionThe success of a Creative Writing class is contingent on the individual instructor’s development and nurturanceof a unique creative culture; therefore this Instructor’s Manual will highlight only the technical aspects of TheBloomsbury Introduction to Creative Writing which might be useful to take into consideration in the planning ofa curriculum based on the book.To begin with, the manual gives an overview of the connections between the exercises in each chapter, someideas for discussion, and a list of readings mentioned in that chapter. This can help with planning a curriculumof various interconnected forms or genres.It is essential to emphasize that the readings referred to in the textbook and in this manual do not replace theinstructor’s own selection of reading material for a Creative Writing class. Students respond best when instructorsteach the literature they are most passionate about. The readings mentioned here are simply additional readingswhich will help to exemplify and contextualize the discussions and exercises in the textbook.In section 3, the manual offers a bonus exercise which could be used as an assessment task for each chapter.In section 4 you will find a glossary of terms for reference.Pedagogically, The Bloomsbury Introduction to Creative Writing presupposes the following:MMMMMMMMIn Creative Writing, formal scholarship complements an independent programme of arts practice byteaching technique as well critical and creative thinking, literary and composition theory, as well literarycitizenship.No Creative Writing course of study takes place solely in the classroom. The exercises in this book offeropportunities to experiment with different writing environments: galleries, cafes, on public transport, inthe kitchen at home.Creative Writing is an art form, and creative writers are artists; therefore students need to be exposed tothe complex connections between writing and life.Scholarly practice-led research and writing methods (which work best alongside foundational knowledgeof literary theory and new criticism) should be introduced early in undergraduate degrees in CreativeWriting for these reasons:MMMMMMMMTo complement the verbal critique process of workshops.To help students think critically about their creative practice in order to develop and improve.To force students to contextualize their own writing by reading and analyzing contemporary andclassical literature, which is important not only for creative development but also in practical terms forfunctioning effectively in the publishing and editing industry.To prepare students for the rigorous scholarly demands of postgraduate study.Furthermore, The Bloomsbury Introduction to Creative Writing is written with the changing climate of humanitiesin academia in mind. On one hand, an acknowledgement that a student does not enrol in a Creative Writingdegree to become qualified to write a novel begs for a holistic approach to scholarship which encompassesknowledge, daily life, and active learning and teaching environments. On the other hand, a growing dissatisfaction with the terminal MFA which has been the standard offering of postgraduate Creative Writing studyinvites a conscientious rethinking of approaches taken in undergraduate degrees which may need to begin topredicate Doctoral and PhD programmes in Creative Writing. For these reasons, The Bloomsbury Introductionto Creative Writing might offer an opportunity for instructors and course convenors to reimagine the balancesof creative and critical, theory and practice, and classroom and real-world learning in existing Creative Writingundergraduate degrees.Alternatively, each chapter of The Bloomsbury Introduction to Creative Writing can be used individually fortheir practical exercises and workshops alongside established modes of study in each form and genre.9781472578440 txt online.indd 103/10/2014 14:36

2The Bloomsbury Introduction to Creative WritingDiscussionsDiscussions on theory, form, and style work as precursors to each progressive series of exercises and workshops.It might be useful to assign the introductions to chapters alongside all addition readings as a jumping-off pointfor in-class discussions. Whereas readings of literature (both the suggested readings for each chapter and thestories and poems chosen by the instructor) are important for understanding the context of each form or genre,the discussions in The Bloomsbury Introduction to Creative Writing are handy ways into explorations of thestudents’ own writing practice.ExamplesSome examples provided are original ones by the author. Others are taken from existing literature, and a comprehensive list of readings for each chapter can be found at the end of this manual.It is perfectly reasonable for instructors to opt not to have students focus on the examples until they havewritten a first draft, or simply to use the examples as counterpoints for discussion in workshopping.There are some students, especially early on in their studies, who have anxiety about taking direction forwriting exercises and the examples might be useful initially to help quell some of this anxiety. It is worth notingwhen students are sticking too closely to the examples provided (it’s much less of a problem if they departexponentially from the examples).ExercisesAside from the exercises that specify they should be done in environments other than the classroom, most of theexercises in the book are designed to work as in-class tasks which should take no more than about 20 minutesto complete.It is important that students are writing both in class and at home every week—if not every day.One suggested class format is to plan a seminar which incorporates one or two of the exercises (depending ontime constraints) alongside a mini-lecture or class discussion and concludes with a workshop session of one ofthe previous week’s exercises (homework might be to redraft exercises done in class, or complete new exercisesfrom the book).WorkshopsThe workshops in the book are also appropriate in-class activities, although, depending on the existing formatfor classes, instructors might organize students into workshop groups that meet outside of class once a week andreport back on their progress in class.It is important that students aren’t expected to simply read their work aloud and discuss it freely early on inundergraduate courses, because, generally speaking, they will get off topic or fail to give and receive really usefulcritical feedback from their peers. The workshops in the book specify different ways of sharing working—forexample, some workshops ask students to swap their draft with another member of the group and listen to theirpartner read their draft out to the larger group. This is a way of forcing students to experiment with the ways theyengage with each other’s work, and with their own work in the redrafting and editing process.Every instructor will have her own way of setting rules or guidelines for workshop participation from the startand the workshops in the book assume this.9781472578440 txt online.indd 203/10/2014 14:36

2. Chapter by Chapter Notesand Reading ListsThis section will explain how some of the exercises in each chapter relate to exercises in other chapters. A listof readings used in each chapter is included, but these shouldn’t limit students from reading a range of complementary texts set by instructors and sourced independently.2.0. IntroductionReadings:Alison Flood, “Philip Roth tells young writer ‘don’t do this to yourself’,” in The Guardian online edition (UK:16 November 2012)Charles Bukowski, “So You Want to be Writer,” in Sifting Through the Madness for the Word, the Line, theWay (New York: HarperCollins, 2009)2.1. Chapter 1: Writing and KnowledgeThe point to the exercises in this chapter is the creation of a sort of creative knowledge database that students canrefer back to for material for the exercises in the following chapters in The Bloomsbury Introduction to CreativeWriting. Most of the exercises are intended to be completed within 15 or 20 minutes, which doesn’t allow muchconceptualization time; so, by collating a series of brainstormed lists in Chapter 1, students will have fallbackmaterial should they fail to have a gut-reaction idea to future exercises.The Stream of Consciousness exercise, particularly, is the foundation for later guided stream-of-consciousnessbased exercises in the Reflection Writing and Feature Planning sections of Chapter 2, the discussions andexercises in Chapter 3, and culminating in an exercise in Chapter 4 which asks the student to use the best partsof previous stream of consciousness exercises in the development of voice.All of these exercises are suitable for in-class or homework tasks, and might provide an interesting forum forstudents to get to know each other before plunging into more intensive workshop situations.Readings:Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, unabridged edition, trans. Norman Kemp Smith (New York: StMartin’s Press, 1965)Matsuo Bash, “Blowing Stones,” in Short Poems, ed. Jean Elizabeth Ward, trans. Robert Hass (Lulu.com,2009) http://books.google.com.au/books/about/Short Poems.html Katie Fischer, “John Slattery is a Natural,” Interview Magazine -nature Lawrence Ferlinghetti, These Are My Rivers: New & Selected Poems 1955-1993 (New York: NewDirections, 1994)9781472578440 txt online.indd 303/10/2014 14:36

4The Bloomsbury Introduction to Creative WritingGeorge Orwell, Keep the Aspidistra Flying (Florida: Harcourt Inc, 1956)Charles Dickens, Great Expectations (London: Penguin Books, 2012)2.2. Chapter 2: Writing the SelfThe exercises in this chapter put the student/author at the centre of the text.The Autobiography and Memoir exercises are an introduction to the storytelling techniques practiced inChapters 4, 5 and 6.The Reflection and Personal Interest Feature Writing exercises are an introduction to the structural andconceptualization aspects of digital media and scholarly writing exercises in Chapters 7 and 8.It is important that students read the essays referenced by George Orwell and Joan Didion both as examplesof the personal essay genre and for their insights into the subject matter of the Why I Write exercise at the endof the chapter.The exercise, Why I Write, is designed partly to motivate students, to get them thinking of themselves as awriter and consciously interrogate their relationship with writing.Readings:George Orwell, “Why I Write,” orwell.ru http://orwell.ru/library/essays/wiw/english/e wiw Ian Jack, “Memoirs are made of this – and that,” in The Guardian online edition (AU: 8 February 2003)Anthony Kiedis and Larry Sloman, Scar Tissue (London: Time Warner Books, 2004)Bob Dylan, Chronicles: Volume One (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004)Joan Didion, “Why I Write,” (Bridgewater: Bridgewater.edu) http://people.bridgewater.edu/ atrupe/ENG310/Didion.pdf 2.3. Chapter 3: Poetics and Poetry CompositionThe intention behind the exercises in this chapter are threefold: first, to begin to link creative writing practicewith poetics; second, to allow students to experiment with forms outside of their comfort zone; third, toemphasize the careful use of language across all genres.Although there are some key poets and poems mentioned in the section on Poetic Movements, these are justan initial guide. Instructors can add examples of different forms they particularly want students to focus on andbuild discussions on those examples from the overview provided in the chapter.The haiku exercise, in particular, is useful as an introduction to narrative structure discussions in the fictionand screenwriting chapters. It asks students to consider the haiku as a whole and experiment with the order andpresentation of images which come together in the haiku to tell a story.It’s also not necessary for students to do the exercises in any particular order, and it may be helpful forthem to be prescribed one exercise to attempt several times over the course of a few weeks to begin to mastera particular form.For courses which focus on Poetry Writing, many of the exercises in this chapter can be completed andworkshopped in class.As students become more confident sharing their drafts, and more familiar with each other’s work, theexercises might build up to an organized public poetry reading outside of class. While this is a big ask for undergraduate students, it’s also a motivating event to work towards.9781472578440 txt online.indd 403/10/2014 14:36

2. Chapter by Chapter Notes5Readings:Poems linked in-text and/or included throughout.2.4. Chapter 4: Fiction ConventionsThe exercises in this chapter build to some extent on the memoir writing exercises from Chapter 2.Given that the first few exercises in this chapter are about micro-short stories, and this is a medium which isreadily publishable with online social media, it might be beneficial to create a blog, Facebook group, or Twitterhashtag and workshop some of the writing online as homework. Students could do this in small workshopgroups, or they could be encouraged to join a whole-class forum online and engage with a larger readershipthat way.The first exercise in this chapter, which gives a short list of “beginnings,” is ideal to use in class as a warm-upwriting task. You might start by explaining the exercise, then projecting the first phrase and begin quiet writingtime for three or four minutes, then stop writing, then replace the first phrase with the second phrase, then stop,and so on. It might help students keep up to give a warning 30 seconds before changing phrases.The exercise on narrative structure is a precursor to the narrative arc discussions and exercises in the followingchapter on screenwriting techniques. This section is designed to get students thinking visually about the macrostructure of stories. It might be useful to relate this to the haiku line-order exercise in the poetry chapter.Ideally students will read the short stories by Virginia Woolf, William Carlos Williams, and Guy de Maupassantbefore doing the related exercises which draw heavily from literary techniques employed in those works. Theseshort stories might be prescribed homework reading and the exercises could be done in class.It’s less necessary for students to read the novels referenced by Sylvia Plath, Harper Lee, and Jane Austen, butthese novels are selected because it is likely students will have been exposed to them in other English courses andwill be familiar with the characters cited in the discussions and exercises.The concluding exercise in genre fiction is simply a fun, optional departure from literary creative writing,which might be helpful as a transition to the more formulaic practice of screenwriting in the following chapter.Readings:Anton Chekhov, “The Slander,” in The Horse Stealer and Other Stories (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1921)Virginia Woolf, To The Lighthouse (London: Urban Romantics, 2012)William Carlos Williams, “The Use of Force,” in The Doctor Series (New York: New Directions, 1984)Guy De Maupassant, “Confessing,” in The Hairpin and Other Stories (Whitefish: Kessinger Publishing,2004)2.5. Chapter 5: Screenwriting TechniquesThe first couple of exercises in this chapter ask students to practice fundamental screenwriting structure andpresentation, and are ideally completed (or at least workshopped) in class so that you can correct technicalerrors before moving on to the more challenging exercises. It’s also preferable for students to practice thesefundamentals—writing out slug lines and formatting action and dialogue correctly—in every exercise in theremainder of this chapter.9781472578440 txt online.indd 503/10/2014 14:36

6The Bloomsbury Introduction to Creative WritingIn introductory Creative Writing classes that teach a combination of prose and script genres, the discussion inthis chapter on the key points of difference between prose writing and screenwriting might happen after studentshave attempted the first exercise as a point of reference.The exercise on subtext and the later exercise on “the bartender, the murderer and the rock star” work beautifully as whole-class instructor-led exercises. They tend to be energizing and give students a taste of what it’s liketo collaborate as a round table of writers.Watch:Pretty Woman, dir. Garry Marshall (1990; Los Angeles: Touchstone Pictures/Silver Screen Partners IV,1990), filmThe Seinfeld Chronicles—Pilot, dir. Art Wolff (1989; Los Angeles: Giggling Goose Productions, Shapiro/West Productions, Castle Rock Entertainment, 1989), televisionSex and the City, dir. Susan Seidelman (1998; New York City; Darren Starr Productions, HBO, RysherEntertainment, 1998), televisionInception, dir. Christopher Nolan (2010; Los Angeles; Warner Bros, Legendary Pictures, Syncopy, 2010),filmWhen Harry Met Sally, dir. Rob Reiner (1989; Los Angeles; Castle Rock Entertainment, Nelson Entertainment, 1989), filmClueless, dir. Amy Heckerling (1995; Los Angeles; Paramount Pictures, 1995), filmReadings:Dara Marks, Inside Story: The Power of the Transformational Arc (London: A & C Black Publishers, 2009)2.6. Chapter 6: Writing for PerformanceOne-act plays, monologue and soliloquy, spoken word are the three parts that make up the chapter on Writingfor Performance, although the focus of the chapter is really on the first two genres and spoken word is includedat the end as a way of getting students to put themselves into the role of performer. It may be worth discussingthe reasons why spoken word fits into this chapter rather than the Poetry chapter as part of a larger discourseon the shared characteristics of poetry and stage writing (for example, sound technique and the oral quality ofboth forms).For the section on one-act plays, instructors might source their local arts body’s guidelines on formatting andhave students adhere to those for practice.Readings:Harold Pinter, The Dumb Waiter (premiered 1960; London, Hampstead Theatre Club), stage playSamuel Beckett, Endgame (premiered 1957; London, Royal Court Theatre), stage playAnton Chekhov, The Marriage Proposal (premiered 1890; St Petersburg), stage play9781472578440 txt online.indd 603/10/2014 14:36

2. Chapter by Chapter Notes72.7. Chapter 7: Writing for Digital MediaThe first section on Digital Storytelling really requires students to watch a few examples of digital stories on theweb to understand their function. Instructors can source these on YouTube and through organizations that usedigital storytelling for a variety of purposes. You could have a discussion on what constitutes a digital story, andwhether all short videos on the web count as digital stories.The Online Media Toolbox section follows on from the feature writing structure exercises in the chapter onWriting the Self.The concluding exercise on social media is intended to get students to think critically about the professionalimplications of a medium they are likely very familiar with, using in their personal life. However, it is possibleto use the social media-based workshop of micro-stories in the chapter on Fiction Conventions as a moreimmersive basis for discussion or point of comparison.2.8. Chapter 8: Critique and ExegesisThe exercises in this chapter ask students to choose a creative piece they wrote for one of the exercises in theprevious chapters and go through the steps of planning a critique of that piece. If your course includes a critiqueelement for their first assessment pieces, the readings and exercises in this chapter might be useful to tackleearlier on in the semester as preparation.9781472578440 txt online.indd 703/10/2014 14:36

3. Bonus Exercises or Assessment Tasks3.1. Chapter 1: Writing and KnowledgeIn this chapter, students are asked to reconsider the meaning and make-up of “knowledge” and apply the possibilities thereof to their own writing practice. This poses an opportunity for a presentation assessment/assignmenttask in the form of a series of panel discussions on the relationship between knowledge and writing. This taskrequires some preparation and should be done in class, as a class:STEP ONE: Ask students to bring in one favorite piece of creative writing they produced before starting thisCreative Writing course. The piece should be no longer than a page or two.Photocopy or electronically distribute each student’s piece so that everyone has access to everyone else’s piece.STEP TWO: According to the subject matter and genres of work you receive, divide students into groups of four,and give each group a week in which they will be required to present their panel discussion.Give each group a topic based on the discussions in this chapter. Topics might include: writer’s block; yourwriter self compared with your social self; emotion as raw material.Before each panel discussion, the students’ homework will be to read the presenting group’s pieces and comeready to ask questions of each presenter.STEP THREE: You, as the instructor, should chair each panel presentation. When a group presents their paneldiscussion, each group member should have a few minutes to talk to the class about how their piece relates to thetopic at hand. After each group member has presented, the class will ask questions of the panel or of individualgroup members.This exercise has the following benefits:MMMMIt is a chance for students to engage in deeper discussions about their writing practice and get to know oneanother, which in turn will foster a healthier workshop dynamic in other tasks.It is an introduction to the idea of a “panel”-style forum which is central to many professional writingconferences, thus giving students a sense of active literary citizenship starting within the classroom.3.2. Chapter 2: Writing the SelfAll the exercises in this chapter focus on the past and present self, but the past and present can tell us a lot aboutthe possibilities for the future. The following task asks students to depart from non-fiction-based self-writing toexperiment with a hybrid of fiction and writing the self.STEP ONE: Students should revisit the exercises in the last two chapters and think about what common threadstie their writings together. Do certain characters or settings recur in several of their exercise responses? Is therean overarching theme of family or friendship? Is there a particular time in their lives that gets more attentionthan other times?STEP TWO: Ask students to workshop their findings about what links they found in their writing to date. Theycan work as a group to discuss the following questions: What part does the practice of writing play in theserecurring themes and ideas? Has the process of exploring certain subjects through writing helped or hinderedthe process of dealing with those subjects in daily life? How does the student envision these themes playing outin their lives ten and 20 years from now?9781472578440 txt online.indd 803/10/2014 14:36

3. Bonus Exercises or Assessment Tasks9STEP THREE: As a homework assignment, students can write a first draft of a fictional story in which they arethe protagonist and some of characters may be based on people they know. The fictional story should be set sometime in the future (at least five years, for greater contrast), and work as a kind of speculation on how some ofthe themes that have preoccupied them in the past might resurface in new and unexpected ways in the future.For example, this might mean imagining how a relationship might heal, alter or break down several years fromnow, or anticipating the way one might overcome an old phobia (by, say, flying for the first time), or the way aperson’s notion of what constitutes a “home” might change given a new set of circumstances.The benefits of this task include:MMMMAside from the obvious catharsis of taking a preoccupation of the past and reimagining it in the contextof the future, the exercise demonstrates the idea that the self in writing is not necessarily a fixed idea—it isopen to interpretation and imagination and change. This concept might be particularly emancipating afterattempting the “Why I Write” personal essay exercise.It’s an interesting exercise for linking self-writing with fiction and screenwriting. It shows students themethod of starting with real life and exploding that into fictional possibilities.3.3. Chapter 3: Poetics and Poetry CompositionThe exercises in this chapter encourage students to experiment with different forms of poetry and ready poetryfrom different eras. This is a good jumping-off point for students to begin to conceptualize and collate a folioof poems which work together as a collection. The following task is probably too long to work as a stand-aloneexercise, but it’s an effective assignment task:STEP ONE: Students can pick their own unifying feature for a poetry folio based on either subject matter orform, or a combination of both. For example, a student might choose to write a short series of poems on death,or a short series of sonnets, or a short series of haikus on love. Ask students to decide on the unifying feature oftheir folio and share with the rest of the class their plan for how and when they will write the poems.STEP TWO: You might allocate a period of two or three weeks in which students have to compose a suite ofbetween four (for longer forms) and 12 (for short forms, like the haiku) poems which adhere to the unifyingfeature they set out for themselves in class.STEP THREE: After the poems are written, you can ask students to write a short critique (see Chapter 8) whichexplains the poetic techniques employed in their poems, justifies their creative choices, elucidates the unifyingfeatures of the poems and their significance, and cites at the work of least two published poets for context.This assignment is suited to both introductory Creative Writing courses and also intermediate-level PoetryComposition courses, and is useful for:MMMMMMIntroducing students to critiquing their own creative process.Giving students the creative freedom to choose their own subject matter and form within a definedframework and with specific goals.Encouraging students two write more poems than they need to submit so that they have a range of workto select from.3.4. Chapter 4: Fiction ConventionsThis chapter includes exercises designed to help students experiment with fiction and storytelling conventionssuch as characterization, setting, voice and plot. Some of the exercises in this chapter also touch on ways to findinspiration for stories and using different stimuli as starting points for new works of fiction.9781472578440 txt online.indd 903/10/2014 14:36

10The Bloomsbury Introduction to Creative WritingThe following task is a departure from the usual fiction writing assignment which offers a writing prompt andword limit. This task is designed to marry experimentation with convention together with the idea of developinggood writing habits, with the intended outcome of helping students find ways of working their writing practiceinto their everyday lives.STEP ONE: Using one of the exercises from the Fiction Conventions chapter in the book as a starting point,students can plan a long-short story in class. The idea is to take an idea and expand on it by embellishing the plot,adding or taking away characters, and exploring the thematic possibilities. Students might be given 20 minutesof class time to write up a synopsis, either in prose form or in dot points.STEP TWO: This part of the assignment can go on for a period of three weeks. Ask students to commit to awriting regime where they must write at least 200 words a day of their story, every day (or five days a week) forthree weeks. You might have students meet up in their workshop groups each week to share drafts and discusstheir progress, or you could dedicate an online forum where students post drafts and comment on each other’swork on a regular basis. By the end of the three-week period, students will have at least 3,000 words of first draftmaterial to work with.STEP THREE: The rewriting phase of the assignment should take one or two weeks. Ask students to continueworking on redrafting and editing their short story every day. They might choose to do one full structural inthe first week, and a closer edit in the second week. Or they might feel they need to do a series of two or threerewrites and copyedit in the last two days. At the end of the rewriting phase, students are ready to submit theirshort story.The purpose of this assignment is to:MMMMMMMMMMEncourage students to start writing a little bit every day.Demonstrate the benefits of working on one piece of creative writing slowly over an extended period oftime, as opposed to banging out work at the last minute.Emphasize the creative process of both writing and rewriting.Challenge students to be accountable to each other and support each other’s writing practice to foster apositive literary community.Have their creative process (as well as the final work they submit) assessed by the instructor.3.5. Chapter 5: Screenwriting TechniquesThis chapter covers both the technical aspects of writing for screen, as well as theoretical thematic approaches toconceptualizing stories for film and television. The exercises in this chapter prepare students for the challengesof writing a screenplay and emphasize the collaborative aspect of screenwriting industry practice. This primesstudents for a screenwriting assignment task:STEP ONE: Organize students into groups of three. In class, have the

MM No Creative Writing course of study takes place solely in the classroom. The exercises in this book offer opportunities to experiment with different writing environments: galleries, cafes, on public transport, in the kitchen at home. MM Creative Writing is an art form, and creative writ