Transcription

705320Teacher Education and Special EducationPugachArticleThe edTPA as an Occasion forStructuring Faculty DialogueAcross the Divide? A “ChecklistManifesto” for a More InclusiveTeacher EducationTeacher Education and Special Education2017, Vol. 40(4) 314 –321 2017 Teacher Education Division of theCouncil for Exceptional ChildrenReprints and ps://doi.org/10.1177/0888406417705320DOI: tesMarleen C. Pugach1AbstractCollaboration across teacher education in the service of a more inclusive preservice pedagogyis now taking place within a context of high intensity accountability that includes the widespreadadoption of the edTPA. This analysis explores how teacher educators in special and generaleducation might advance the preparation of preservice students for inclusive teaching whenfaculty are obliged to use the edTPA to measure candidate learning. Drawing on Atul Gawande’s(2009) work in the field of medicine related to the value of using checklists to improve outcomesamong experts in practical settings, the author proposes the Teacher Education for InclusionChecklist. This tool is designed to help overcome the underappreciated power of the historicaldivide between general and special education, which often serves as a default position for howteacher educators work together, and to provide guidance for how faculty might engage indialogue across the assessments mandated by the edTPA.Keywordsteacher performance assessment, edTPA, inclusion, teacher preparation practices and outcomes,Atul Gawande, collaboration, preservice teacher educationToday, the preparation of special educationand general education teachers has becomeinextricably linked as a way of making goodon the promise of a more inclusive educational practice on the part of the nation’steachers. That every teacher should be prepared for inclusive classrooms and schoolshas increasingly become a reliable tropewithin preservice discourse. Given the consistency of the call for all teachers to beready to teach students with disabilities—those in general education classrooms aswell as their special education counterparts—it seems both valuable and timely toconsider the function of current teacher performance assessment tools, such as theedTPA, in terms of their role in fosteringproductive collaborative relationships amongteacher educators. Ideally, faculty engage inrelationships that would enable them to drawon the data that performance assessmentsgenerate as a way of energizing the preservice curriculum around the agenda of a moreinclusive educational practice—one thatretains a strong respect for the differentialexpertise of special and general educationteachers, while also valuing their collaboration.1University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, USA.Corresponding Author:Marleen C. Pugach, PO box 413, Milwaukee, WI 53202,USA.Email: mpugach@uwm.edu

PugachHowever, we have been at the project ofimproving the preparation of general and special education teachers in relationship to inclusive practice for quite some time—in fact, sincethe inception of modern special education lawin 1975 (Pugach, 2005; Pugach, Blanton, Mickelson, & Kleinhammer-Trammill, 2013). Giventhis long history, and in light of the ongoing difficulties children and youth with disabilitiescontinue to experience in their school outcomes,the purpose of this exploration is twofold. First,I describe how the historic divide between general and special education often functions as adurable, implicit default in terms of how general and special education faculty conduct theirwork together. This default dynamic can serveas a powerful deterrent to collaboration in thecontext of how performance assessment dataare used, and as such, can subtly undermine thegoal of joint preservice work across the variouskinds of expertise teacher educators possess. Ifthis situation is not attended to deliberately, theway faculty engage with the data generated bythe performance assessments mandated by theedTPA—notwithstanding its flaws—could wellbe subject to this same problematic dynamic.As a way of counteracting the risk of thisdefault, I propose a new tool designed to support teacher educators in bridging the longstanding divide between special and generalpreservice education. Based on the work ofAtul Gawande (2009), noted doctor and medical journalist, related to the role of checklists inpractical settings to maximize the effectivenessof outcomes, this proposed tool is a checklistdesigned to support faculty when they areobliged to use the edTPA as a principal measure of candidate learning. As teacher educators work together to more effectively advancethe curriculum for preservice candidates, sucha checklist has the potential to help offset thedivide in which we still seem to be mired.The Divide as Default: AnUnderappreciated ProblemIn computer science, the term default is conceptualized as a preexisting standard (TechnicalTerms: Default, 2016); it is the fallback in theabsence of a readily available option. Similarly,315the historic separation between preservice general and special education, with all its attendantexplanations and regrets and baggage, functionsas a kind of default in relationship to inclusiveteaching practice. When we fail to envision analternative, we can all too easily backslide towhat we know and have always done, theequivalent preservice “standard operating procedure.” As the default, this deep divisionbetween general and special education lurks inthe background; it is what we revert to when noexplicit alternate preservice path is apparent. Incontrast to the collaboration and coordinationthat are required to move forward jointly—aswell as to capitalize on the distinctive expertiseamong teacher educators that can work in amutually reinforcing relationship—in the specific case of advancing teacher education relative to a more inclusive practice, that standardoperating procedure tilts toward this deepseated duality. And what is most familiar andcomfortable and easiest in teacher education isseparating the responsibility for “general” and“special” education; it is what we know bestand it is the way business has typically beendone.Cochran-Smith and Dudley-Marling (2012)identified three main issues they believe contribute to maintaining such a divide. Theyinclude the following: (a) the different disciplinary influences foundational to special andgeneral education, in particular, special education’s behavioral roots compared with anemphasis on sociocultural learning in generaleducation; (b) negative connotations associated with the prefix “dis” in disability relativeto the social construction of failure in school;and (c) the contrast between a commitment toaccess to the general education curriculum onthe part of special education and the social justice goal of redefining the curriculum in relationship to an equity agenda on the part ofgeneral teacher education. But it is how suchdivisions play out in the routine daily interactions among teacher education faculty thatundergird the notion of and resonate with theidea of the divide as the default position.For example, the well-established messages that are enacted daily in terms of facultycommunication and discourse illustrate this

316default. They can include the overt or impliedbelief that “it’s not my job”—that is, “it’s notmy job” to know and/or teach about eithergeneral or special education in the preservicecurriculum. Subtle blaming of faculty for notbeing more interested in or knowledgeableabout relevant general or special educationissues can also take place—usually outside offormal meetings. Furthermore, an imbalanceis often conveyed in terms of who is viewed asthe learner among the faculty; this oftenappears as a one-way street where those ingeneral education are expected to “learn”about special education—less often the otherway around. Yet, there is ample expertise to beappreciated and called upon across teachereducators—in academic content areas, inmulticultural and bilingual education, in critical theory and critical race theory, in learningand development, in culturally relevant pedagogy, as well as in special education. Despitethe best of intentions, and depending on thecontext, messages like these can work inintentional, unintentional, conscious, unconscious, subtle, tacit or overt ways to undermine building strong, reciprocal relationshipsacross teacher educators that can help overcome the distance. As such, messages likethese form the discursive backbone of thedefault.The divide is also apparent in day-to-daydecision making regarding teacher education.At the local level, it can be represented in howassumptions about leadership of local, stateand national teacher education reforms areenacted, for example, failing to create sharedleadership across general and special education for any variety of initiatives, or includingonly a token general or special educator (ornone at all) on a given relevant project orgrant application. In the absence of suchshared responsibility, opportunities for joint,collective dialogue, action, and policy makingare short circuited from the outset.Given over 40 years of history of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act(IDEA), with its commitment to fostering amore inclusive practice, such questions aboutthe relationship between general and specialteacher education should have been settledTeacher Education and Special Education 40(4)long ago. Failing to acknowledge the influence of the divide in terms of how teachereducation is carried out on a day-to-day basisis likely to be holding us back from makinggreater progress in figuring out how best toprepare every teacher for his or her work withstudents who have disabilities. I would like tosuggest that the divide between general andspecial education is a vastly underappreciated problem that requires unflinching, consistent transparency to counteract its effects.As such, the challenge for the next generationof teacher educators is to better address thecomplexity of the enterprise of preparingteachers for inclusive practice. This complexity includes overcoming not only the day today trappings of the divide but also dealingwith seminal issues such as the place of disability within the larger commitment to socialjustice (Cochran-Smith & Dudley-Marling,2012; Pugach, Gomez-Najarro, & Mukhopadhyay, 2014), the potential coexistence of arange of instructional strategies that may seemat odds philosophically but that may all beneeded to respond effectively to the full rangeof students, and the structure of clinical experiences.The edTPA as a Manifestation ofthe DivideThe vision of teaching reflected in the edTPAas it relates to general and special educationserves as one illustration of the dominant roleof the divide as default. In a comparative analysis of the 2013 edTPA Special EducationAssessment Handbook with the 2013 Elementary Literacy Assessment Handbook, Pugachand Peck (2016) documented the clash of pedagogies and philosophies revealed across thesetwo teacher performance assessments. Drawing on Cultural Historical Activity Theory,they argued that in light of the fact that theseassessments represent such different views ofpedagogy and philosophy, the edTPA appearsto function as cultural tool that reproduces,however unconsciously, the historic dividedrelations between special and general education. For example, having teachers collaborateacross general and special education—a staple

317Pugachof inclusive practice—is not given emphasis ineither the general or the special educationassessment (Pugach & Peck, 2016).Furthermore, the vision of instruction represented in the edTPA special educationassessment is limited to a narrow band of pedagogy (Ledwell & Oyler, 2016; Pugach &Peck, 2016), consistent with Cochran-Smithand Dudley-Marling’s (2012) identification ofconflicting philosophies of learning as onefactor contributing to the split. In addition, theedTPA does not emphasize ways to createlearning opportunities and “access points” tothe general education curriculum (Ledwell &Oyler, 2016, p. 129). The revised 2016 version of the edTPA special education assessment handbook has not altered this situationsignificantly, as it sustains a focus on the individual student in isolation, minimizing theclassroom context in which most of the education of students with disabilities takes placetoday. In Ledwell and Oyler’s (2016) inquiryinto the early effects of this assessment on thepreservice curriculum, one of the participating faculty observed that the edTPA “justseems to have very little to do with what actually happens particularly in inclusive environments” (p. 129). The development of theedTPA, then, constitutes a robust expressionof the dominance of the default position relative to the relationship between general andspecial education, and however unintentionally, is a stark reminder of the need to interrupt the default in a purposeful manner.“Minding the Gap” as a PathForwardIn Europe and in the Middle East, one oftensees a warning in train stations to “mind thegap” as you cross from the platform to thetrain. The idea of “minding the gap” seems fitting here: How might we better “mind thegap” between teacher educators in generaland special education? In this case, the gapcan be viewed as the distance between ourconventional, dualistic ways of behaving (the“default”), and ways of behaving that mightmore productively, and jointly, lead to improving the preservice curriculum and clinicalexperiences such that new teachers havegreater skills and confidence to work not onlywith students with disabilities, but to expandtheir pedagogical range for all students. Thisgap is complicated by the fact that there isvaluable expertise on the part of both generaland special educators alike that needs to bedrawn upon to solve the complex problem ofpreparing new teachers well for effectiveinclusive practice. Furthermore, teacher educators face challenges both in figuring outhow disability and diversity fit together(Cochran-Smith & Dudley-Marling, 2012;Pugach, Blanton, & Florian, 2012; Pugachet al., 2014; Villegas, 2012) and over whatkinds of curriculum and instruction might bestsupport an inclusive practice across the division that exists (Cochran-Smith & DudleyMarling, 2012).How might we overcome these limitationsand “mind the gap”? How might we movefrom tacit to transparent, and from incidentalto consistent, in how we work together? Howmight we more consistently push back againstthe default position? One path forward is togenerate structured, practical tools to helpinterrupt the discourse and culture of division,tools that instead have the potential to facilitate a richer discourse of inclusion in teachereducation, leading to more productive action.This is precisely where Atul Gawande’s workon checklists comes in.Gawande’s ChecklistManifesto: A Tool forMinding the GapAtul Gawande, the renowned surgeon andmedical journalist, is the author of numerousarticles and books that bring unusual clarity toa host of medically oriented issues—amongthem his 2009 book titled The Checklist Manifesto. In it, he describes the value of checklistsused by highly skilled professionals (e.g., surgeons, builders, and airplane pilots) to assure ahigher quality of practice and improved outcomes. What is striking about his descriptions,which include several vignettes about theeffectiveness of such checklists in various professional settings, is their simplicity and

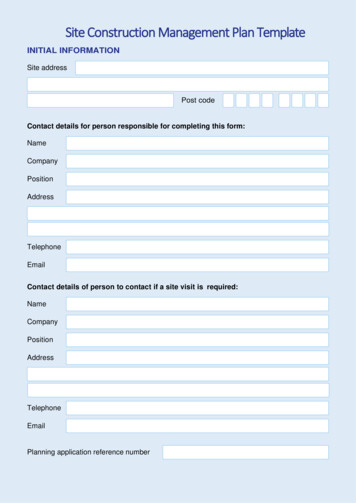

318directness, as well as the fact that they havebeen effective in improving both practical outcomes and communication among high-endprofessionals—professionals who possess agreat deal of knowledge and talent. Gawande(2009) argues that checklists are “simple toolsaimed to buttress the skills of expert professionals” (p. 128). They can be most importantassuring more positive outcomes, he notes,“when expertise is not enough” (p. 31). Hemaintains thatwhen we look closely, we recognize the sameballs being dropped over and over, even bythose of great ability and determination. Weknow the patterns. We see the costs. It’s time totry something else. (p. 186, emphasis added)Checklists, he says, “remind us of the minimum necessary steps and make them explicit”(p. 36). So in operating rooms, for example,nurses and technicians might have to remindsurgeons about what should be a routine practice that could minimize infection. Checklistscan also be used to structure how meetingstake place, for example, having each participant state their concerns at the outset, givingvoice to all attending, and reducing the penchant to sit on one’s concerns, which can stifleparticipation. But according to Gawande, thedeeper purpose of a checklist is not “just ticking boxes” (p. 160). Instead, they can helpprofessionals in “embracing a culture of teamwork and discipline . . . ” (p. 160). Such asense of discipline is not particularly evidentin how we have been considering the preservice curriculum and clinical experiences relative to preparing new teachers for inclusivepractice, nor in how we are obliged to assesstheir professional learning.In our long-standing attempts to achieverobust teacher education redesign for inclusion, we have not yet found consistentanswers, the same proverbial ball has beendropped over and over with regard to the division between general and special preserviceeducation, and with few exceptions, our common patterns of discourse and practice havenot been successful in assuring a more uniformly effective preparation for general andTeacher Education and Special Education 40(4)special education teachers with regard toteaching students with disabilities. That islikely one reason why we have arrived at ateacher performance assessment that reifiesthe divide. And that is precisely why Gawande’s work seems to have relevance for thisparticular educational dilemma.In many fields, Gawande (2009) noted, wetend not to attend to failures—nor do we especially like to. “We don’t look for the patternsof our recurrent mistakes or devise and refinepotential solutions to them” (p. 185). He continues, “but we could, and that is the ultimatepoint” (p. 185). Yet, despite the fact thatchecklists can be effective in purposefullyreminding us that we have to be unambiguousabout the things we want/need to get right,their use can also engender discomfort amongprofessionals. About surgeons in particular,Gawande (2009) observed,We don’t like checklists. They can bepainstaking. They’re not much fun. But I don’tthink the issue here is mere laziness itsomehow feels beneath us to use a checklist, anembarrassment. It runs counter to deeply heldbeliefs about how the truly great among us—those we aspire to be—handle situations of highstakes and complexity. The truly great aredaring. They improvise. They do not haveprotocols and checklists. (p. 173)Faculty in the academy are likely to respondsimilarly; we are comfortable with our expertstatus and tend to be less comfortable beingput in a position where we have to engage inteamwork, share the stage, and perhaps evendisplay our need to learn something new ortake a different perspective. As a rule, those inthe academy do not much care for not beingright, for needing some kind of direction. Fundamentally, Gawande is telling us to get overit—that checklists might, just might, help.The Teacher Education forInclusion ChecklistThe Teacher Education for Inclusion Checklist, displayed in Figure 1, is designed to provide a similar kind of support to skilled teacher

319PugachBefore the Mee ng/A er the Mee ngDuring the Mee ngWho owns the work?Who owns the work?Confirm that project leadership includesappropriate, representa vestakeholdersDoes the project leadership share fullresponsibility for the ac vi es?Are “silo talk”, jargon, labeling, andsubtle blame being pointed out?What is the goal?Is the goal of the project clear andagreed on by the leadership? (i.e., goalis not to “put” special educa on into thecurriculum)How is project progress beingcommunicated?Does wri en communica on go outunder shared leadership/mul plenames?Do par cipants and leaders have atechnical site for shared, opencommunica on?Is someone tasked with mindingparticipation?Is there always more than oneperson working the checklist?Confirm that par cipants represent all appropriate and relevant exper seConfirm that all par cipants have introduced themselves and stated anyconcernsAre “silo talk”, jargon, labeling, and subtle blame being pointed out?What is the goal?Is goal of mee ng/project clear? (e.g., goal is not to “put” special educa on intothe curriculum)Is “teacher educa on for inclusion” clearly defined, taking into account the fullrange of students’ social iden ty markers?Are faculty engaged in mutual learning? About each other’s work andcommitments?How is diversity being defined?Is learning about diversi es viewed as an equal challenge across par cipants?Are students not essen alized according to single markers of social iden ty?Are connec ons across diversi es, cri cal theory, and culturally relevantteaching made?Are connec ons across diversi es limited to dispropor onality?How is learning/instruc on conceptualized?Are varied instruc onal approaches/philosophies viewed as having the poten alto coexist to meet the full range of student needs?Are instruc onal prac ces being considered across social iden ty markers?Are the limita ons of accommoda on and modifica on explored in rela onshipto the Universal Design of Learning?Is the rela onship between the exper se of general and special educato rs beingar culated clearly?Figure 1. The Teacher Education for Inclusion Checklist.education experts as the checklists Gawande(2009) is advocating. As Figure 1 indicates, it“checks up” on shared leadership andexpanded participation across general and special education. This checklist begins to makeexplicit that faculty would approach conversations about the preservice curriculum andassessments relative to preparing teachers forstudents with disabilities as more open learners, more willing listeners, with an eye towarda more complex view of diversity as well asinstruction, giving recognition to the role thedefault can play in such deliberations.While checklists have been developed tosupport inclusive practice at the PK-12 level(e.g., Federico, Herald, & Venn, 1999; Villa &Thousand, 2016), tools such as these aredesigned as resources that PK-12 school faculty, and staff have the option of accessing tohelp guide their work. In teacher education,however, such tools are rare. Gawande’s concept of the role of checklists, however, differssignificantly from how they are typicallyused; he views their implementation as essen-tial for improving practice. They are designedto make transparent what should be evident onthe part of professionals. Furthermore, hisvision is imbued with a sense of deep urgencyin terms of the need to attend to the issues andpractices any particular checklist is designedto address so that practice across professionals can be elevated to high levels of accomplishment.It is this sense of urgency, coupled with aspecific delineation of practices that continueto hold back the quality of joint work acrossteacher educators in general and special education, which provides the impetus for achecklist focused on teacher education forinclusion. The issues it represents are thosethat we may often think we have alreadymoved beyond in our deliberations, things wethink we may not have to attend to directly. Infailing to attend to these issues directly, wemay also be failing to build a solid foundationupon which to solve the more complex dilemmas of preservice practice across general andspecial education.

320How might such a checklist function withrespect to the edTPA? On one hand, as areflection of the duality between general andspecial education, the edTPA poses a dilemmafor teacher educators relative to the aspirational agenda of a more inclusive practice ofteaching. On the other hand, performanceassessments like these generate assessmentdata that can reasonably be expected to forman important source for faculty dialogue andcollaboration across teacher educators fromgeneral and special education as they work tobuild better understandings regarding practices that may be viewed as “belonging” togeneral education and those that may beviewed as “belonging” to special education.As such, the edTPA generates data that represent a useful shared text to support greaterfaculty dialogue. Disciplined by the use ofsuch a checklist, teacher educators have theopportunity to engage jointly in active interpretations of the assessment data, especiallywhere similarities exist across assessments.Examples of such similarities in educational concepts, as well as in the language ofpractice, exist across edTPA assessments ingeneral and special education and include (butare not limited to) the following: the languagedemands of particular lessons and learningtasks, the importance of monitoring studentlearning, establishing and maintaining arespectful classroom environment for learning, and drawing on students’ cultural andcommunity assets (Pugach & Peck, 2016).These constitute an initial set of issues teachereducators might investigate together, usingthis focus as an opportunity to examine relationships across the content and structure ofpreservice programs in relationship to howcandidates are responding to these aspects ofthe assessments.The goal of such a checklist, then, is not toassist teacher educators in addressing candidate preparation for successful performanceon the edTPA. Rather, its purpose is to stimulate greater inclusivity within teacher education, with the edTPA serving as an immediate,visible focal point around which teacher education faculty can come together in a morestructured way. The checklist provides a set ofTeacher Education and Special Education 40(4)transparent guiding steps that to date have notbeen made explicit, but which, if followed,might contribute to correcting conventionalteacher education practices that have oftenstymied the pressing foundational work ofprogram reform.ConclusionAlthough as teacher educators we expectour graduates to engage in professionallearning communities as they move intoPK-12 practice, we are not necessarily thatgood at doing so ourselves. Teacher education faculty typically do not function, norregularly view themselves, as members of alocal professional community of learnersacross areas of teacher education expertisefocused on the continuous improvement ofpreservice teacher education (Blanton &Pugach, 2017). When joint experiences dotake place relative to preparing teachers forinclusion, they often tend to be decontextualized within specific courses or clinicalexperiences rather than as an organic function of the preservice curriculum. Thisdynamic pertains across an array of preservice practices, including how we assesscandidates and how we use the data generated by such performance assessments toinform our work.Perhaps because it is such an apt illustration of the isolated ways teacher educatorstend to operate by default, even within a context that often reflects a philosophical inclination toward more rather than less inclusivepractice, the edTPA provides a new occasionfor faculty in teacher education to attempt toengage together in transformative programmatic dialogue. Functioning as a learningcommunity, with a straightforward set of stepsto counteract the divide, the opportunity existsto build a greater shared understanding andpractice of what it means to learn to teachfrom a more inclusive perspective. TheTeacher Education for Inclusion Checklistserves as one modest contribution toward creating a sense of urgency and professionalresponsibility to advance this crucial educational goal.

321PugachDeclaration of Conflicting InterestsThe author(s) declared no potential conflicts ofinterest with respect to the research, authorship,and/or publication of this article.FundingThe author(s) disclosed receipt of the followingfinancial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Several of the ideas inthis article were first presented in a keynoteaddress, Imagining the Next Generation of TeacherEducation for Inclusion, presented at the 2016annual spring meeting of the California Council onTeacher Education (CCTE) in San Jose, California.That address was jointly funded by CCTE and theCollaboration for Effective Educator Development, Accountability, and Reform (CEEDAR)Center, University of Florida. CEEDAR is a project of the U.S. Department of Education, Office ofSpecial Education Programs, Award No.H325A12003. Bonnie Jones and David Guardinoserve as the project officers. The views expressedherein do not necessarily represent the positions orpolicies of the U.S. Department of Education. Noofficial endorsement by the U.S. Department ofEducation of any product, commodity, service, orenterprise mentioned in this article is intended orshould be inferred.ReferencesBlanton, L. P., & Pugach, M. C. (2017). A dynamicmodel for the next generation of research onteacher education for inclusion. In L. Florian,& N. Pantić (Eds.), Teacher education for thechanging demographics of schooling: Issuesfor Research and Practice (pp. 215-228).Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer.Cochran-Smith, M., & Dudley-Marling, C. (2012).Diversity in teacher education and specialeducation: The issues that divide. Journal ofTeacher Education, 63, 237-244.Federico, M. A., Herald, W. G., & Venn, J. (1999).Helpful tips for successful inclusion: A checklist for educators. Teaching ExceptionalChildren, 31, 76-82.Gawande, A. (2009). The checklist manifesto: Howto get things right. New York, NY: Picador.Ledwell, K., & Oyler, C. (2016). Unstandardizedresponses to a “standardized” test: The edTPAas gatekeeper and curricular change agent.Journal

A “Checklist Manifesto” for a More Inclusive Teacher Education Marleen C. Pugach1 Abstract Collaboration across teacher education in the service of a more inclusive preservice pedagogy is now taking place within a context of h