Transcription

Museum Data Exchange:Learning How to ShareFinal Report to The Andrew W. Mellon FoundationGünter WaibelRalph LeVanBruce WashburnOCLC ResearchA publication of OCLC Research

Museum Data Exchange: Learning How to ShareMuseum Data Exchange: Learning How to ShareWaibel, et. al., for OCLC Research 2010 OCLC Online Computer Library Center, Inc.All rights reservedFebruary 2010OCLC ResearchDublin, Ohio 43017 USAwww.oclc.orgISBN: 1-55653-424-8 (978-1-55653-424-9)OCLC (WorldCat): 503338562Please direct correspondence to:Günter WaibelProgram Officerwaibelg@oclc.orgSuggested citation:Waibel, Günter, Ralph LeVan and Bruce Washburn. 2010. Museum Data Exchange: Learning How toShare. Report produced by OCLC Research. Published onlineat: ry/2010/2010-02.pdfWaibel, et. al., for OCLC ResearchFebruary 2010Page 2

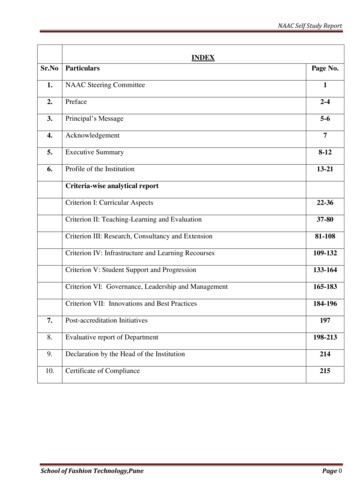

Museum Data Exchange: Learning How to ShareContentsExecutive Summary . 6Introduction: Data Sharing in Fits and Starts . 8Early Reception of CDWA Lite XML. 10Grant Overview . 11Phase 1: Creating Tools for Data Sharing . 12COBOAT and OAICATMuseum 1.0: Features and Functionality. 14Implementing and Refining the Suite of Tools . 16Phase 2: Creating a Research aggregation . 17Legal agreements . 17Harvesting Records. 17Preparing for Data Analysis . 19Exposing the Research Aggregation to Participants. 21Phase 3: Analysis of the Research Aggregation . 22Getting Familiar with the Data. 23Conformance to CDWA Lite, Part 1: Cardinality. 26Excursion: the Default COBOAT Mapping . 28Conformance to CDWA Lite, Part 2: Controlled Vocabularies . 29Economically Adding Value: Controlling More Terms. 32Connections: Data Values Used Across the Aggregation . 2010-02.pdfWaibel, et. al., for OCLC ResearchFebruary 2010Page 3

Museum Data Exchange: Learning How to ShareEnhancement: Automated Creation of Semantic Metadata Using OpenCalais . 37A Note about Record Identifiers . 38Patricia Harpring’s CCO Analysis. 40Third Party Data Analysis . 41Compelling Applications for Data Exchange Capacity. 41Conclusion: Policy Challenges Remain. 44Appendix A: Project Participants . 46Appendix B: Project Related URLs for Tools and Documents. 47Bibliography . 48Notes: . 50FiguresFigure 1. Draft system architecture for a CDWA Lite XML data extraction tool . 13Figure 2. Block diagram of COBOAT, its modules and configuration files . 15Figure 3. Excerpt from a report detailing all data values for objectWorkType from a singlecontributor . 20Figure 4. Excerpt of a report detailing all of units of the information containing a data valueacross the research aggregation . 21Figure 5. Screenshot of the no-frills search interface to the MDE research aggregation . 22Figure 6. Records contributed by MDE participants . 24Figure 7. Use of CDWA Lite elements and attributes in the context of all possible units ofinformation . 24Figure 8. Use of possible CDWA Lite elements and attributes across contributing institutions,take 1 . 2010-02.pdfWaibel, et. al., for OCLC ResearchFebruary 2010Page 4

Museum Data Exchange: Learning How to ShareFigure 9. Use of possible CDWA Lite elements and attributes across contributing institutions,take 2 . 26Figure 10. Any use of CDWA Lite required / highly recommended elements . 26Figure 11. Any use of CDWA Lite required / highly recommended elements . 27Figure 12. Use of CDWA Lite required / highly recommended elements by percentage . 28Figure 13. Match rate of required / highly recommended elements to applicable controlledvocabularies . 30Figure 14. Top 100 objectWorkTypes and their corresponding records for the MetropolitanMuseum of Art . 32Figure 15. Top 100 nameCreators and their corresponding records for the Harvard ArtMuseum. 33Figure 16. Most widely shared values across the aggregation for nameCreator,nationalityCreator, roleCreator and objectWorkType. 35Figure 17. nationalityCreator: relating records, institutions, and unique values . 36Figure 18. objectWorkType: relating records, institutions, and unique values . 36Figure 19. Screenshot of a search result from the research aggregation . 39Figure 20. objectWorkType spreadsheet (excerpt) for CCO analysis, including evaluationcomments . 40Figure 21. Overall scores from CCO evaluation—each bar represents a museum . 2010-02.pdfWaibel, et. al., for OCLC ResearchFebruary 2010Page 5

Museum Data Exchange: Learning How to ShareExecutive SummaryThe Museum Data Exchange, funded by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, brought together a groupof nine museums and OCLC Research to create tools for data sharing, build a research aggregationand analyze the aggregation. The project established infrastructure for standards-based metadataexchange for the museum community and modeled data sharing behavior among participatinginstitutions.ToolsThe tools created by the project allow museums to share standards-based data using the OpenArchives Initiative Protocol for Metadata Harvesting (OAI-PMH). COBOAT allows museums to extract Categories for the Description of Works of Art (CDWA)Lite XML out of collections management systems.OAICatMuseum 1.0 makes the data harvestable via OAI-PMH.COBOAT’s default configuration targets Gallery Systems’ TMS, but can be adjusted to work withother vendor-based or homegrown database systems.Both tools are a free download mdata/.Configuration files adapting COBOAT to different systems can be shared /. For more detail, see Phase 1: Creating tools for Data Sharing on page 12.Data Harvesting and AnalysisHarvesting data from nine museums, the project brought together 887,572 records in a non-publicresearch aggregation, which participants had access to via a simple search interface. The analysisshowed the following: for CDWA Lite required and highly recommended data elements, 7 out of 17 elements areused in 90% of the contributed recordsthe match rate against applicable Getty vocabularies for objectWorkType, nameCreator androleCreator is approximately 40%the top 100 objectWorkType and nameCreator values represent 99% and 49% of allaggregation records brary/2010/2010-02.pdfWaibel, et. al., for OCLC ResearchFebruary 2010Page 6

Museum Data Exchange: Learning How to ShareSignificant improvements in the aggregation could be achieved by revisiting data mappings to allowfor a more complete representation of the underlying museum data. Focusing on the top 100 mosthighly occurring values for key elements will impact a high number of corresponding records, andwould be low-hanging fruit for data clean-up activities.For further analysis, the research aggregation will be available for third party researchers under theterms of the original agreements with participating museums. For more detail, see Phase 2: Creating a Research Aggregation on page 17 and Phase 3: Analysis of the Research Aggregation on page 21.ImpactIn its relatively short life span to date, the project’s suite of tools has catalyzed several data sharingactivities among project participants and other museums: The Minneapolis Institute of Arts uses the tools in a production environment to contributedata to ArtsConnected, an aggregation for K-12 educators.The Yale University Art Museum and the Yale Center for British Art use the tools to share datawith a campus-wide cross-search, and contribute to a central digital asset managementsystem.The Harvard Art Museum and the Princeton University Art Museum are actively exploring OAIharvesting with ARTstor. (Three additional participants have signaled that this would be alikely use for their OAI infrastructure as well.)Participating vendors contributed to the museum community’s ability to share: Gallery Systems extended COBOAT for EmbARK, demonstrating the extensibility of the MDEapproach.Selago Design created custom CDWA Lite functionality for MIMSY XG, freely available tocustomers as part of their OAI tools.An increasing number of projects and systems using CDWA Lite / OAI-PMH as a component (forexample OMEKA, Steve: The museum social tagging project, CONA ) can be seen as a leadingindicator for the future need of data sharing tools like the ones created as part of the Museum DataExchange. When there are applications for sharing data which directly support the museum mission,more data is shared, and museum policies evolve. Conversely, when more data is shared, more suchcompelling applications emerge. For more detail, see Compelling Applications for Data Exchange Capacity on page /2010-02.pdfWaibel, et. al., for OCLC ResearchFebruary 2010Page 7

Museum Data Exchange: Learning How to ShareIntroductionData Sharing in Fits and StartsDigital systems and the idea of aggregating museum data have a longer history than the availabilityof integrated access to museum resources in the present would suggest. As early as 1969, a newlyformed consortium of 25 US art museums called the Museum Computer Network (MCN) and itscommercial partner IBM declared, “We must create a single information system which embraces allmuseum holdings in the United States” (IBM et al. 1968). In collaboration with New York University,and funded by the New York Council of the Arts and the Old Dominion Foundation, MCN created a“data bank” (Ellin 1968, 79) which eventually held cataloging information for objects from manymembers of the New York-centric consortium, including the Frick Collection, the Brooklyn Museum,the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art,the National Gallery of Art and the New York Historical Society (Parry 2007).However, using electronic systems with an eye towards data sharing was a tough sell even back inthe day: when Everett Ellin, one of the chief visionaries behind the project and then AssistantDirector at the Guggenheim, first shared this dream with his Director, he remembers being told:"Everett, we have more important things to do at the Guggenheim" (Kirwin 2004). The end of the talealso sounds eerily familiar to contemporary ears:“The original grant funding for the MCN pilot project ended in 1970. Of the original fifteenpartners, only the Metropolitan Museum and the Museum of Modern Art continued to catalogtheir collections using computerized methods and their own operating funds.” (Misunas et al.)Today, the museum community arguably is not significantly closer to a “single information system”than 40 years ago. As Nicholas Crofts aptly summarizes in the context of universal access to culturalheritage: “We may be nearly there, but we have been “nearly there” for an awfully long time.” (Crofts2008, 2)Not for lack of trying, however, as a non-exhaustive selection of strategies and experiments tostandardize museum data exchange in the US highlights: The AMICO Library of digital resources from museums (conceived in 1997, a full year beforeeXtensible Markup Language (XML) became a W3C recommendation) created a data formatconsisting of a field-prefix (such as OTY for Object Type) and the field delimiter “} ” toexchange information (AMICO).In 1999, a consortium of California institutions (MOAC) implemented a mark-up standardfrom the archival community (Encoded Archival Description or EAD) to bring their resourcesinto an existing state-wide aggregation of library special collections and archival /2010/2010-02.pdfWaibel, et. al., for OCLC ResearchFebruary 2010Page 8

Museum Data Exchange: Learning How to Share Between 1998 and 2003, the CIMI consortium launched a range of projects exploring datastandards and protocols for exchange, including Z39.50, Dublin Core and the UK standardSPECTRUM.All of these initiatives had merit in their particular historical context as well as a heyday of adoption,yet none of these strategies achieved consensus and wide-spread use over the long term.The most contemporary entry in the history of museum data sharing is Categories for the Descriptionof Works of Art (CDWA) Lite XML (Getty Trust 2006). In 2005, the Getty and ARTstor created this XMLlaschema “to describe core records for works of art and material culture” that is “intended forcontribution to union catalogs and other repositories using the Open Archives Initiative (OAI)harvesting protocol” (Getty Research Institute n.d.). Arguably, this is the most comprehensive andsophisticated attempt yet to create consensus in the museum community about how to share data.The complete CDWA Lite data sharing strategy comprises: A data structure (CDWA) expressed in a data format (CDWA Lite XML)A data content standard (Cataloging Cultural Objects—CCO)A data transfer mechanism (Open Archives Initiative Protocol for Metadata Harvesting—OAIPMH)What follows is a brief example of how these different specifications work hand in hand to establishstandards-based, shareable data: CDWA, a data field and structure specification, defines a discrete unit of information such as“Creation Date” with sub-categories for “Earliest Date” and “Latest Date.”CCO, a data content standard, specifies the rules for formatting a date as “Late 14th century”for display and using an ISO 8601 format “1375/1399” for machine indexing.CDWA Lite XML, a data format, allows the encoding of all this information, as shown in thecode snippet below: cdwalite:displayCreationDate Late 14th century /cdwalite:displayCreationDate cdwalite:indexingDatesWrap cdwalite:indexingDatesSet cdwalite:earliestDate 1375 /cdwalite:earliestDate cdwalite:latestDate 1399 /cdwalite:latestDate /cdwalite:indexingDatesSet /cdwalite:indexingDatesWrap OAI-PMH, a data exchange standard, allows sharing the resulting record. The protocolsupports machine-to-machine communication about collections of records, includingretrieval from a content provider’s server by an OAI-PMH harvester. It also supportssynchronizing local updates with the remote harvester as the museum data evolves (Elingsand Waibel 2007).The Museum Data Exchange (MDE) project outlined in this paper attempts to lower the barrier foradoption of this data sharing strategy by providing free tools to create and share CDWA Lite XMLdescriptions, and helps model data exchange with nine participating museums. The activities weregenerously funded by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and supported by OCLC Research incollaboration with museum participants from the RLG Partnership. The project’s premise: whiletechnological hurdles are by no means the only obstacle in the way of more ubiquitous data sharing,having a no-cost infrastructure to create standards-based descriptions should free institutions 2010-02.pdfWaibel, et. al., for OCLC ResearchFebruary 2010Page 9

Museum Data Exchange: Learning How to Sharedebate the thorny policy questions which ultimately underlie the 40 year history of fits and starts inmuseum data sharing.Early Reception of CDWA Lite XMLThe launch of CDWA Lite XML was officially announced at the MCN annual conference in Boston onNovember 5, 2005. The following two data points help illuminate its reception by the community.A small survey among ten prominent museums from the RLG Partnership (seven from the UnitedStates, two from the United Kingdom, one from Canada) conducted by Günter Waibel approximatelysix months after the initial launch of CDWA Lite XML showed that: Capabilities for exporting standards-based data of any kind (including CDWA Lite XML) arenon-existent.Policy issues are a major obstacle to providing access to high-quality digital images. Nomuseum provides free access to publication-quality digital images of artworks in the publicdomain without requiring a license (one museum has plans), while nine museums licensepublication-quality digital images for a fee.A limited amount of data sharing already happens, primarily with subscription-basedresources. While eight museums provide access to digital images on their Web site, fourmuseums contribute to licensed aggregations such as ARTstor or CAMIO, and two contributeto non-licensed aggregations such as state-wide or national projects.Approximately 18 months after the launch of CDWA Lite XML, the newly minted CDWA Lite AdvisoryCommittee 1 surveys the cultural heritage community writ large to gauge the impact of CDWA Lite,and finds the following: CDWA Lite XML garners great interest: 144 respondents (50.7% from museum community)start the 22 question survey.Even among the self-selecting group of those taking the survey, few have the experience tocomplete it: only the first three questions have responses from a majority of respondents,while the numbers drop precipitously once questions presuppose basic working knowledgeof CDWA Lite. Only 22 individuals complete the survey.Given this backdrop, an RLG Programs/OCLC working group called “Museum Collection Sharing,”(OCLC Research n.d.c) inaugurated in May 2006, sought to support increased use of the fledglingCDWA Lite strategy by providing a forum for museum professionals to share information andcollaborate on implementation solutions. The group identified the following hurdles for gettingmuseum data into a shareable format: The complexities of mapping data in collections management systems to CDWA LiteThe absence of mechanisms to export data out of collections management systems andtransform it into CDWA Lite XMLThe complexities of configuring and running an OAI-PMH data content providerCircumstances made the creation of an OAI-PMH data content provider which “speaks” CDWA LiteXML the lowest-hanging fruit on the list. In their proof-of-concept project with ARTstor, The Getty hadimplemented a modified version of OAICat, an open source OAI data provider originally written 2010-02.pdfWaibel, et. al., for OCLC ResearchFebruary 2010Page 10

Museum Data Exchange: Learning How to ShareJeff Young (OCLC Research). In collaboration with the working group and supported by Jeff, OCLCResearch released a CDWA Lite enabled version of OAICat (OAICatMuseumBETA) in the fall of 2007.Unfortunately, parallel investigations into widely applicable mechanisms to create CDWA Lite XMLrecords did not immediately bear fruit. For example, the working group discussed the possibleapplication of OCLC’s Schema Transformation technology (OCLC Research n.d.b) with Jean Godby(OCLC Research) and explored Crystal Reports, a report writing program bundled with manycollections management systems, to output CDWA Lite XML. However, the release ofOAICatMuseumBETA provided the impetus for funding from The Andrew W. Mellon foundation toremedy a situation in which museums on the working group had a tool to serve CDWA Lite XMLrecords, yet had no capacity to create these records to begin with.Grant OverviewThe grant proposal funded by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation in December 2007 with 145,000 2contained the following consecutive phases, which will also structure the rest of this paper.Phase 1: Creation of a Batch Export CapabilityThe grant proposed to make a collaborative investment into a shared solution for generating CDWALite XML, rather than many isolated local investments with little community-wide impact. Grantparticipants aimed to leverage the experience some institutions on the Museum Collection Sharingworking group had gained from exploring local solutions to create a common solution. The YaleUniversity Art Gallery, for example, had started developing a command-line tool using customizableSQL files which create database tables corresponding to CDWA Lite; the Metropolitan Museum of Artwas working with ARTstor on a CDWA Lite / OAI data-transfer solution as part of the Images forAcademic Publishing (IAP) program. To keep the grant manageable and within budget, we limitedour investigation to an export mechanism for Gallery Systems’ TMS, the predominant databaseamong the museums in the Collection Sharing cohort.Museum partners: Harvard Art Museum (originally Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the grant migratedwith staff from the MFA to Harvard early in the project); Metropolitan Museum of Art; National Galleryof Art; Princeton University Art Museum; Yale University Art Gallery.Phase 2: Model Data Exchange Processes through the Creation of a ResearchaggregationThe grant proposed to model data exchange processes among museum participants in a low-stakesenvironment by creating a non-public aggregation with data contributions utilizing the tools createdin Phase 1, plus additional participants using alternative mechanisms. The grant purposefullylimited data sharing to records only—including digital images would have put an additional strain onthe harvesting process, and added little value to the predominant use of the aggregation for dataanalysis (see Phase 3 on the next page).Museum partners: all named in Phase 1, plus the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Victoria & AlbertMuseum (both contributing through a pre-existing export mechanism); in the process of the grant,data sets from the Minneapolis Institute of Arts and the National Gallery of Canada were also 010/2010-02.pdfWaibel, et. al., for OCLC ResearchFebruary 2010Page 11

Museum Data Exchange: Learning How to SharePhase 3: Analysis of the Research AggregationThe grant proposed to surface the characteristics of the research aggregation, both its potentialutility and limitations, through a data analysis performed by OCLC Research. The CDWA Lite / OAIstrategy had been expressly created to support large-scale aggregation—however, would themuseum data transported by these means actually come together in a meaningful way?A minimal interface to the research aggregation would make cross-collection searching available tomuseum participants.Museum partners: all nine institutions named under Phase 1 and Phase 2.All individuals who had a significant role in the activities surrounding the grant are acknowledged inAppendix A. Project Participants (page 45).Phase 1: Creating Tools for Data SharingThe first face-to-face project meeting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in January 2008 resulted inthe following draft system architecture for a data extraction tool, which distilled our far-rangingdiscussions around the required functionality into a single graphic.This quote, like Figure 1 taken from the original meeting minutes, explains the envisioned flow of thedata:“The Data Extraction Tool obtains data from the Source Database through application of SQLbased mapping profiles. It will store the resulting output in a new and separate CDWA Lite WorkDatabase that resides on a server behind the institution’s firewall. The Work Database providesan efficient means of representing the data defined by the CDWA Lite standard and the OAIheader. A Database Publishing Tool will be configurable to push data across the firewall to thePublic OAI CDWA Lite XML Database. In addition, the tool will be capable of publishing CDWALite XML records with an OAI wrapper to the Public OAI CDWA Lite XML File System, or CDWA LiteXML records with or without and OAI wrapper to an Internal CDWA Lite XML File System. Eitherthe public File System or XML Database could be accessed by an OAI repository to respond toHTTP queries from the Web.”While Figure 1 and its description hint at the emerging complexity of the grant’s endeavor, some ofthe devils are still hiding in the details. For example, even a tool providing a solution solely for TMSneeds to support significant variability in the source data model: it needs to adapt to a variety ofdifferent product versions of TMS used by different project participants, as well as differentimplementations of the same product version by different project participants. In addition, the toolneeds to adapt to a variety of different practices within an institution: the Metropolitan Museum, forexample, is running twenty installations of TMS controlled by different departments, while for otherparticipants, a single instance of TMS within a museum contains considerable variability becausedifferent departments use that single instance according to different ary/2010/2010-02.pdfWaibel, et. al., for OCLC ResearchFebruary 2010Page 12

Museum Data Exchange: Learning How to ShareFigure 1. Draft system architecture for a CDWA Lite XML data extraction toolSupporting crucial OAI-PMH features created additional requirements for the tool: it needs to keeptrack of updates to the TMS source data so it only regenerates CDWA Lite XML for updated records,and is capable of communicating these updates through OAI-PMH. In addition, the tool needs to beable to mark records as belonging to an OAI-PMH set so museums can create differently scopedpackages of metadata for different harvesters.In short, our first project meeting surfaced a mismatch between required features, timeline andbudget for Phase 1 of the grant. In addition, the meeting exposed tension between the open sourcerequirement of the grant, and official policies at the majority of participating museums, which didnot have resources for open source development, and supported Microsoft Windows exclusively.While everybody around the table wanted to create an open source solution, lack of support foropen source within the group constituted a serious risk factor for successful implementation.Apparently, others shared the concern that overall requirements, timeline and budget for the projectwere out of sync. The response from open source developers in the museum community whoreceived our RFP was tepid, and only one party wanted to discuss details.Ben Rubinstein, Technical Director at Cognitive Applications Inc. (Cogapp), a UK consulting firm witha long track-record of compelling museum work, presented us with an intriguing s

COBOAT allows museums to extract Categories for the Description of Works of Art (CDWA) Lite XML out of collections management systems . OAICatMuseum 1.0 makes the data harvestable via OAI -PMH.