Transcription

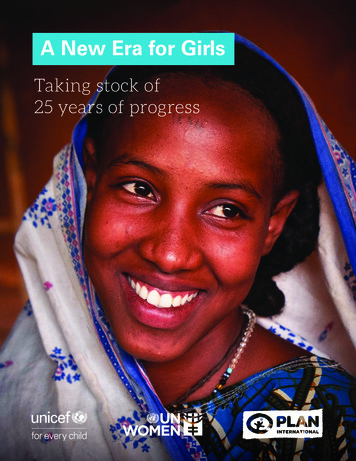

ForewordA New Era for GirlsTaking stock of25 years of progress1

AcknowledgementsThe preparation of this report was initiated and coordinated by the Gender Section,Programme Division, UNICEF. Lauren Pandolfelli and Kusum Kali Pal, Division of Data,Analytics, Planning and Monitoring, were responsible for data analysis and interpretation ofthe results, with inputs from Jan Beise, Claudia Cappa, Liliana Carvajal, Allysha Choudhury,Aleya Khalifa, Chibwe Lwamba, Colleen Murray and Nicole Petrowski, as well as VladimiraKantorova and Mark Wheldon of UN Population Division. Kimberly Chriscaden, LaurenPandolfelli and Leigh Pasqual were responsible for report writing.Valuable insights were received from Shelly Abdool, Patty Alleman, Prerna Banati, Elana Banin,Gerda Binder, Lara Burger, Sheeba Harma, Karen Humphries-Waa, Shoubo Jalal, Shreyasi Jha,Vrinda Mehra, Suguru Mizunoya, Catherine Muller, Maha Muna, Lauren Rumble and SagriSingh from UNICEF; Ginette Azcona and Laura Turquet from UN Women; and Leila Asrari,Jessica Malter and Selamawit Tesfaye from Plan International.Editing: Naomi LindtDesign and layout: Cecilia Silva VenturiniPlease contact:Gender Section, Programme Division3 UN Plaza, New York, NY ed Citation: United Nations Children’s Fund, UN Women and Plan International,A New Era for Girls: Taking Stock of 25 Years of Progress, New York, 2020. United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), March 2020

Contents4Taking stock5Foreword6Reflecting on a quarter century of progress10Education empowers girls for life and work18Gender-based violence and harmful practices violategirls’ rights26Girls face heightened health risks in adolescence36Prioritizing actions with girls38Endnotes

4A New Era for Girls I Taking stock of 25 years of progressTaking stockNearly 64 million girls were bornin 1995, the year the BeijingDeclaration and Platform for Actionwas adopted, beginning their livesas the global community committedto improving their rights. In 2020,nearly 68 million girls are expectedto be born. The analysis presentedin this report shows that while girls’lives are better today than theywere 25 years ago, these gainsare uneven across regions andcountries. This is particularly true foradolescent girls.To accelerate progress, girls needto be involved in both the decisionmaking and designing of solutionsthat impact their future. This reportdemonstrates the need to focuson the realities girls face todayand addresses the critical issuesof ending gender-based violence,child marriage and female genitalmutilation (FGM); making suregirls have access to 12 years ofeducation and the skills they needfor the workforce; and improvinggirls’ health and nutrition. Thisanalysis is not intended to be anexhaustive assessment of girls’rights and well-being, but rather areview of progress for girls in keydimensions of their lives. It drawsupon internationally comparable timeseries data to assess advancementsagainst the strategic objectives forgirls set out in the Beijing Platformfor Action 25 years ago. Where alack of data prevents trend analysis,the current situation of girls ishighlighted.The evidence provides a foundationfor recommendations to global,national and regional stakeholderson important actions that wouldenable girls to successfully transitioninto adulthood with the ability tomake their own choices and with thesocial and personal assets to live afulfilled life.

ForewordForewordToday’s more than 1.1 billion girls arepoised to take on the future. Everyday, girls are breaking boundaries andbarriers to lead and foster a safer,healthier and more prosperous worldfor all. They are tackling issues likechild marriage, education inequality,violence, climate justice, andinequitable access to healthcare. Girlsare proving they are unstoppable.Back in 1995, the world adoptedthe Beijing Declaration andPlatform for Action – the mostcomprehensive policy agenda forgender equality – with the visionof ending discrimination againstwomen and girls. But today, 25years later, discrimination andlimiting stereotypes remain rife.Girls’ life expectancy has extendedby eight years, yet for many thequality of that life is still far fromwhat was envisioned. Girls havethe right to expect more. Therealities they face today, in contextsof technological change andhumanitarian emergencies, are bothremarkably different from 1995 andmore of the same: with violence,institutionalized biases, poor learningand life opportunities, and multipleinequalities unresolved. There aremajor breakthroughs still to be made.There are many success stories:Fewer girls are getting married orbecoming mothers, and more areHenrietta H. ForeExecutive Director, UNICEFin school and literate – acquiringkey foundational skills for lifelongsuccess. But progress has beenuneven and far from equitable.Girls from the poorest householdsor living in fragile or humanitariansettings are not benefiting fromthe expansion in education, whilethe girls who are in school arestruggling to secure the qualityeducation they need to compete ina rapidly changing workforce, wheredigital and transferable skills, likecritical thinking and confidence, areindispensable.Today, no matter where a girl lives,she is risk of encountering violencein every space – in the classroom,home and community. And thetypes of violence she will comeinto contact with have becomeincreasingly complex with the rise oftechnology. However, technology hasalso opened up opportunities for girlsto grow their networks and learndigital and transferable skills that willprepare them for life and work.stigma, limited age-appropriateinformation, fear of side effects orlimited decision-making autonomy.In 2020, a gender-equitable worldis still a long way off. The nextsteps for change must meaningfullyinclude girls as decision-makers anddesigners of the solutions to thechallenges and opportunities theyface every day.Girls are rights holders andequal partners in the fight forgender equality. They representa tremendous engine fortransformational change towardsgender equality. They deserve thefull support of the global communityto be empowered to successfullytransition to adulthood with theirrights intact, able to make their owninformed choices and with the socialand personal assets acquired to livefulfilled lives.To have an education and a future,girls must also be healthy. Yet, whenit comes to making decisions abouttheir health and well-being, girls stillface significant barriers to accessingand benefiting from health servicesto meet their specific needs, suchas those related to sexual andreproductive health – due to cost,We know the best advocates forgirls are girls. Every girl is a powerfulagent of change in her own right.And, when girls come together todemand action, shape policies, andhold governments to account, wecan together change our schools,families, communities and nationsfor the better. As leaders, it’s ourduty to bridge the generations,working with and for today’s girls toraise their voices and achieve theirdreams.Phumzile Mlambo-NgcukaExecutive Director, UN WomenAnne-Birgitte AlbrectsenCEO, Plan International5

6A New Era for Girls I Taking stock of 25 years of progressReflecting on a quartercentury of progressThe world is home to more than1.1 billion girls under age 18, whoare poised to become the largestgeneration of female leaders,entrepreneurs and change-makers theworld has ever seen. Girls are livinglonger lives than they were 25 yearsago, when nations committed toadvancing gender equality as part ofthe Beijing Declaration and Platformfor Action.Girls born today can expect tolive nearly eight more years, onaverage, than girls born in 1995.1That’s eight more years to liveout their dreams, to participate indecisions that affect their lives, andto lead positive change in society.Yet, girls continue to face enormoushurdles in a world that still largelyfavours boys and men. Girls are stillexcluded from decision-making thatimpacts their lives, and the mostmarginalized girls – those fromethnic minorities, indigenous groupsand poor households; living in ruralor conflict settings; and living withdisabilities – face additional layers ofdiscrimination.Discrimination and harmful gendernorms starting at birth (and insome places before birth throughfemale foeticide) set limits on whatbehaviours or opportunities areconsidered appropriate for girls.These beliefs are often entrenchedin laws and policies that fail touphold girls’ rights, such as rights toinheritance. At least 60 per cent ofcountries still discriminate againstdaughters’ rights to inherit land andnon-land assets in either law orpractice.2

Reflecting on a quarter century of progressI am glad to be a girl becausewhen girls are given the chance,we will fight for our rights andpass on what we have learnedto other girls who are facing thesame situations.”Zaharah, age 16,from UgandaGender discrimination not onlyrestricts girls’ abilities to accumulatehuman, social and productive assets,limiting their future educationaland employment opportunities,but also hinders their well-beingand diminishes their self-belief.As a result, by the time girls reachadolescence, many are left dreaminginstead of achieving.When it comes to education today,fewer girls are out of school. Nearlytwo in three girls are enrolled insecondary school compared to one intwo in 1998. However, we are facinga globally recognized “learning crisis”;this means, even when girls are inschool, many do not receive a qualityeducation. Many are not developingthe transferable skills, like criticalthinking and communication, or digitalskills needed to compete in today’slabour market and gig economy. Infact, worldwide, nearly one in four girlsaged 15–19 years is neither employednor in education or training comparedto 1 in 10 boys of the same age.The risk of violence in every space– online and in the classroom,home and community – similarlykeeps girls from achieving. Thirteenmillion girls aged 15–19 years haveexperienced forced sex in theirlifetimes. Meanwhile, even thoughharmful practices such as childmarriage and FGM have declined inthe past 25 years, they continue todisrupt and damage the lives andpotential of millions of girls globally.Further, conflict and displacementonly heighten the risk and realitiesof gender-based violence. As girlslose their support systems andhomes, and are placed in insecureenvironments and in new roles,their risk of gender-based violence,including sexual violence, intimatepartner violence, child marriage andabuse, increases.While fewer adolescent girls arebecoming mothers today, they stillface a high risk of sexually-transmittedinfections and anaemia – risks thatincrease when they struggle to accessage-appropriate health services andinformation. This is nowhere moreobvious than in the case of HIV, whereadolescent girls continue to bear thebrunt of the virus’s effects. Globally,970,000 adolescent girls aged10–19 years are living with HIV today,compared to 740,000 in 1995.7

8A New Era for Girls I Taking stock of 25 years of progressGirls are a unique group requiring focused commitmentsThe global community has goodcause to celebrate the progressachieved over the last quarter centuryin the name of girls’ rights. But wecannot lose sight of the challengesgirls still face every day.There is no definition ofwhat it means to be a girl.What a man can do,a woman can do, too.I believe life would bebetter if we didn’t havethose stereotypes.”Lan*, Grade 10, Viet Nam*name changed to protect identityTwenty-five years ago, the BeijingPlatform for Action recognized thatchildhood is a separate space fromadulthood. Girls’ needs, preferencesand vulnerabilities are related towomen’s, but are also distinct. ThePlatform called upon governments,donors and civil society to invest inending discrimination against girls andeliminating barriers in health, nutrition,education and related domains thatprevent them from realizing theirfull potential. It also called upongovernments to ensure that all datais disaggregated and analysed bysex and age so governments canformulate policies and programmes,and make decisions that betterprotect and support girls in achievingbrighter futures.Adopted in 2015, the 2030 Agendafor Sustainable Development renewsthe commitment to creating aworld where all girls are healthy andprotected, learn and have a fair chanceto succeed. But, commitment hasnot led to direct investments: Only afraction of international aid dollars isspent on meeting the needs of girls.3Similarly, even forward-looking policiesand programmes addressing girls’challenges specifically, including skillsdevelopment for employability, oftenstart only after adolescent girls havetransitioned into adulthood, missingthe millions of girls that have neverset foot in school and live in poverty.Limited investment in these key areasmeans girls are already lagging behindwhen it comes to achieving equalparticipation in society as adults.Likewise, programmes andinterventions to support adolescentgirls are often disjointed, and theyfall through the gaps in approachesonly targeted at either childrenor women. For example, effortsto end child marriage are oftendisconnected from efforts to supportschool retention or secure sexualand reproductive health. Adolescentgirls’ challenges and the solutions tothem must be addressed holistically,as success in each area pushesprogress in another.For progress to be achieved,girls’ voices and solutions musttake centre stage, and theglobal community, includinggovernments, civil societyorganizations, multilaterals,statisticians and the privatesector must work with girlsto take actions that set themup to succeed.Empowering girls will require theglobal community to: Expand opportunities for girls tobe the changemakers, activelyengaging their voices and opinionsin their communities and politicalprocesses about any decisionthat relates to their bodies,education, career and future. Allactions should place girls’ voicesand solutions at the centre – nodecisions for girls, without girls. Scale up investments in girls’programming models that willaccelerate progress alignedwith today’s reality, includingin developing adolescent girls’education and skills for the FourthIndustrial Revolution; endinggender-based violence, childmarriage and FGM; and ensuring

Reflecting on a quarter century of progressMy family’s situation and thechallenges I face every day toattend school will not stop mefrom continuing to fight for mydreams. I worry that some of myfriends are not studying due tolack of money or because theyare not interested in educationor because their family does notsupport them. I always advisethem to return to school if theywant to have a better future.”Timotea, age 14, from Guatemalagirls have accurate, timely andrespectful health informationand services. This also includesbuilding synergies and expandingpartnerships between adolescentgirls’ skills development andwomen’s economic participation toaddress persistent gender divides inareas such as science, technology,engineering, and math (STEM). Boost investments into theproduction and intersectionalanalysis of high quality, timelysex-and age-disaggregated data forchildren and adolescents, includingadolescents aged 10–14 years,particularly in areas where dataare limited, such as gender-basedviolence, twenty-first century skillsacquisition, adolescent nutrition,and mental health.Additionally, to ensure all girls livea fulfilled life, data must makemarginalized girls visible. This includesgirls living with disabilities, in poorhouseholds and in rural areas, fromethnic minorities and indigenousgroups, in fragile and conflict settingsand those who may be marginalizeddue to sexual orientation or genderidentity. This would drive evidenceinformed policy and programmedecisions for adolescent girls,alongside better accountability.Once girls have gained the righttools and the space to strengthentheir engagement and leadership,they will be well placed to shapethe world around them, openingdoors for them to be at the heartof decision-making processes thataffect their lives.9

10 A New Era for Girls I Taking stock of 25 years of progressEducation empowers girlsfor life and workPrimary education provides childrenwith the foundation for a lifetime oflearning, while secondary educationequips them with the knowledge andskills needed to become empoweredand engaged adults. The benefitsof secondary education for girls aresignificant. Compared to girls withonly a primary education, girls withsecondary education are less likelyto marry and become pregnant asadolescents. And, while womenwith primary education earn onlymarginally more than womenwith no education, women withsecondary education earn twiceas much, on average, compared towomen who never went to school.4Critical to ensuring girls completeschool is a home environmentthat prioritizes learning anda safe and supportive schoolenvironment with functioningtoilets, a relevant curriculum,and trained teachers.Even so, completing secondaryschool is insufficient if girls donot acquire a quality educationwith transferable skills, suchas critical thinking and problemsolving and digital skills, both ofwhich are needed in the labourforce. These are necessary forfuture employability, yet too manyeducation systems worldwide failto deliver a quality education thatsupports girls in their transition fromschool to work.

Education empowers girls for life and workThe number of girls out of school worldwide dropped by 79 million between 1998 and 2018Figure 1. Number of out-of-school children, by level of education and sex, 1998–2018MaleWorld in 1998400382.3 millionFemalePrimary ageLower secondary age350Upper secondary age90.8 million300World in 2018258.3 million82.2 millionNumber (in millions)At the primary level, the number fellby more than half, from 65 million to32 million (see Figure 1). Regionally,while fewer girls are out of schooltoday in East Asia and the Pacific,and in South Asia (14 million and 45million, respectively), the reverseis true in sub-Saharan Africa. Whilefewer girls of primary-school ageare out of school today in theregion, 2 million more girls of lowersecondary age and 5 million moregirls of upper-secondary age are outof school today (see Figure 2). Thisis because enrollment rates havenot kept pace with the increasein the school-age population inthe region, which is home to thefasting growing child population,worldwide.25067.0 million20052.5 million70.8 million15044.7 million10029.8 million65.1 million31.6 million5032.3 million47.0 million26.8 million01998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018Globally, in 1998, there weremore girls of secondary schoolage out of school than boys(143 million girls compared to127 million boys). Today, theopposite is true: There are 97million girls of secondary schoolage out of school compared to102 million boys.Still, despite the remarkablegains made for girls in the pasttwo decades, they are still moredisadvantaged at the primary level,with 5.5 million more girls than boysof this age out of school worldwide.Added to this, global progress inreducing the number of out-ofschool children at the primary levelhas stagnated for both girls andboys since 2007.Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), September 2019.Figure 2. Number of out-of-school children, by sex, level of education, select regions,1998*and 201845414038353130Number (in millions)Gender disparities in the numberof out-of-school children have alsonarrowed substantially over thepast two decades. At the secondarylevel, they have shifted to thedisadvantage of 01897532117151532750Girls BoysEast Asiaand the PacificGirls BoysGirls BoysGirls BoysSouth AsiaSub-SaharanAfricaEast Asiaand the PacificPrimary ageGirls BoysGirls BoysGirls BoysGirls BoysSouth AsiaSub-SaharanAfricaEast Asiaand the PacificSouth AsiaLower secondary age1998Girls BoysSub-SaharanAfricaUpper secondary age2018Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), September 2019.Note: *For South Asia, the first data point for lower secondary age and upper secondary age is 1999.11

12 A New Era for Girls I Taking stock of 25 years of progressToday, two in three girls of secondary school age globally are enrolled in secondary school comparedto only one in two in 1998Since 1998, globally, the gender gap in primary school enrolment hasnarrowed from 6 percentage points to 2 percentage points. And at thesecondary level, the gender gap has closed (see Figure 3).Figure 3. Net enrolment rate, by sex and education level, 1998–2018100Primary school agePercentage80Secondary school oysSource: UNESCO Institute for Statistics, September 2019.While all regions have seen increases in girls’ secondary school enrolment over the past two decades,there are wide regional variations todayFigure 4. Female net enrolment ratio, by education level and region, 1999 and 7167Percentage676057544034331820East Asiaand the PacificEurope andCentral AsiaLatin America andthe Caribbean1999Middle East andNorth AfricaNorth AmericaSouth AsiaSecondary agePrimary ageSecondary agePrimary ageSecondary agePrimary ageSecondary agePrimary ageSecondary agePrimary ageSecondary agePrimary ageSecondary age0Primary ageBetween 1999 and 2018, theproportion of secondary schoolage adolescent girls enrolledin secondary school increasedfrom three in five to four in fivein East Asia and the Pacific andfrom 33 per cent to 60 per centin South Asia. During this sameperiod, girls’ secondary schoolenrolment rose from 57 per centto 71 per cent in the Middle Eastand North Africa while in subSaharan Africa, only 34 per centof girls of secondary school ageare enrolled in secondary schooltoday compared to 18 per cent in1999 (see Figure 4).Sub-SaharanAfrica2018 (or the latest year)Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), September 2019.Note: *For East Asia and the Pacific and sub-Saharan Africa, the latest available data for primary age education are2015 and 2009, respectively.

Education empowers girls for life and workWorldwide, four of five girls complete primary school but only two of five complete upper secondaryschoolFigure 5. Completion rate, by sex and education level, entage4842443835293020East Asiaand the PacificGlobalLatin America andthe CaribbeanMiddle Eastand North AfricaUpper secondary ageLower secondary agePrimary ageUpper secondary ageLower secondary agePrimary ageUpper secondary ageLower secondary agePrimary ageUpper secondary ageLower secondary agePrimary ageUpper secondary ageLower secondary agePrimary ageUpper secondary age0Lower secondary age10Primary ageIn all regions, girls and boys areequally likely to complete primaryschool (see Figure 5). But at thesecondary level, gender parity incompletion rates is not sustainedacross all regions. For example, inEast Asia and the Pacific and LatinAmerica and the Caribbean, girls aremore likely than boys to completeupper secondary school, but in SouthAsia and sub-Saharan Africa, thereverse is true. Only 38 per cent ofgirls in South Asia and 29 per cent ofgirls in sub-Saharan Africa completeupper secondary school. And girlsfrom the poorest households areoften doubly disadvantaged. In lowincome countries, for instance,only 8 per cent and 2 per cent ofgirls from the poorest householdscomplete lower secondary and uppersecondary school, respectively.5Sub-SaharanAfricaSouth AsiaSource: UNICEF global databases, 2019, based on DHS, MICS, other national surveys and data from routine reportingsystems.Note: *Data refer to the most recent year available during the period specified in the chart title. Data were insufficient tocalculate a regional average for Europe and Central Asia and North America.The number of female youth aged 15–24 years who are illiterate declined from 100 million to 56million between 1995 and 2018, but 1 in 10 female youth remain illiterate todayFigure 6. Literacy rate among youth aged 15–24 years, by region and sex, 1995–20189699 999390 888010099 99100PercentageLiteracy, a basic foundational skillnecessary for personal growth andactive citizenship, has increasedglobally among youth over thepast 25 years, but a gender gapat the expense of girls persists.Adolescent girls and young womenaged 15–24 years make up 56 percent of the global illiterate youthpopulation today compared to 61per cent in 1995. South Asia hasseen the most progress for girls.In 1995, 7 in 13 female youth wereliterate compared to 11 in 13 femaleyouth, today. In sub-Saharan Africa,the region with the widest genderdisparity in youth literacy rates, justunder three in four adolescent girlsand young women are literate today(see Figure 4019952018World19952018East Asiaand thePacific19952018Europe andCentral Asia19952018Latin Americaand theCaribbeanFemaleSource: UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), September 2019.Note: Data were not available for North America.19952018Middle Eastand NorthAfricaMale19952018South Asia19952018Sub-SaharanAfrica13

14 A New Era for Girls I Taking stock of 25 years of progress

Education empowers girls for life and workAdolescent girls outperform boys in reading while math performance is more variedAssessing the relative achievementsof girls and boys in secondary schoolprovides insights into whethereducation systems are meetingthe needs of girls and boys equally.Skills in reading and mathematicsare critical for anyone’s successfulentry into the labour market. Theseskills also serve as the foundationfor others, such as digital literacy.At the end of lower secondary school,girls outperform boys in reading acrossall countries with available data. Inmath proficiency, results are morevaried, with girls performing better thanboys in about half of the countrieswith available data (see Figure 7).While there has been much debateabout the factors that account forgender differences in educationalattainment, emerging evidenceof the role of positive gendersocialization, both at school andat home, suggests that parents,teachers and policymakers can fosterfoundational skills in reading andmath in all children.6Lower expectations of girls’performance in subjects other thanreading and a lack of role modelsbecome barriers for girls to developessential skills for future careers,such as digital skills or skills inscience, technology, engineering,and math (STEM). This in turndecreases their perceptions ofself-efficacy and ability and canlead to girls being excluded fromdeveloping skills crucial to engagein the Fourth Industrial Revolution,such as innovative and criticalthinking, problem solving andentrepreneurship. As a result, manyadolescent girls leave school withoutthe skills required to succeed intwenty-first century jobs.Figure 7. Percentage of children and young people at the end of lower secondary school achieving at least a minimum proficiency level in readingand math, by sex, 2010–2017*Boys (percentage)100100Higher proportion of boysachieving reading r proportion of girlsachieving reading proficiencyHigher proportion of boys achievingmathematics proficiency10Higher proportion of girlsachieving mathematics proficiency00010203040506070809010001020Girls (percentage)East Asia and the PacificEurope and Central Asia30405060708090100Girls (percentage)Latin America and the CaribbeanMiddle East and North AfricaNorth AmericaSouth AsiaSub-Saharan AfricaSource: United Nations Statistics Division, 2019.Note: Minimum proficiency level is the benchmark of basic knowledge measured through school-based learning assessments. Each dot represents a country, with x- and y-axesindicating the proportions of girls and boys in the country achieving minimum proficiency, respectively. The diagonal line represents the gender parity line. Data points below thegender parity line represent countries where higher proportions of girls than boys reach proficiency.15

16 A New Era for Girls I Taking stock of 25 years of progressIn more than five of six countries with available data, girls aged 10–14 years are more likely than boys of thesame age to spend 21 or more hours on household chores per weekStarting in childhood, girls areoften assigned more householdchores than boys. This is oftendue to gender norms that deemdomestic responsibilities aswomen’s and girls’ work. Incountries in West and CentralAfrica in particular, the genderdisparity in time spent onhousehold chores is stark.For example, in Burkina Faso,girls aged 10–14 years are threetimes more likely than boys ofthe same age to engage in 21 ormore hours of household chores(see Figure 8).Household chores are a normalpart of family life – for both girlsand boys – and are not alwaysdetrimental to children’s healthand well-being. But, it is theamount of time spent on choresthat can curtail girls’ opportunitiesto enjoy the pleasures ofchildhood, including time to play,build social networks and focuson their education.7 The typesof chores girls typically perform,including cooking, cleaning andcaring for others, also lay thegroundwork for girls to assumea disproportionate level ofresponsibility for these activitiesas women, limiting their ability toenter and advance in the labourmarket.8Figure 8. Percentage of adolescents aged 10–14 years who, during the reference week, spentat least 21 hours on unpaid household services, by sex, BurundiBurkina FasoComorosNigerMaliCentral African atic Republic of the CongoEl SalvadorAngolaMongoliaUgandaCôte d'IvoireGuineaNepalTogoSao Tome and PrincipeGuinea-BissauHaitiMalawiGha

Contents 4 Taking stock 5 Foreword 6 Reflecting on a quarter century of progress 10 Education empowers girls for life and wo