Transcription

April-June 2017Volume 26: Number 2Book ReviewThe Color of Law: A Forgotten Historyof How Our Government SegregatedAmerica, by Richard RothsteinBrian KnudsenWhen Frank Stevenson came towork in Richmond, California duringWorld War II, he found that little appetite existed for residential racial integration. The white residents of ruralMilpitas,California got wind in 1953that the Ford Motor Company plantemploying Stevenson and 250 otherAfrican Americans would be relocating to their town, and they quicklysnapped into action. In a scene thatplayed out in many locales across theU.S. during the last century, the citizens of Milpitas incorporated their cityand passed an emergency exclusionaryzoning ordinance banning apartmentconstruction and allowing only singlefamily homes. Federal Housing Administration (FHA) approval, necessary to finance construction of low-costsubdivisions in Milpitas and elsewhere,explicitly prohibited home sales toBlacks. With no apartments to rent andexcluded from the single-family market, for twenty years Stevenson endured a daily six-hour round-trip commute to and from his residence in Richmond California’s Black ghetto.In his new book, The Color of Law,Richard Rothstein recounts this andBrian Knudsen, bknudsen@prrac.org, is Research Associate at the Poverty & Race Research Action Council.other stories to portray the immensecosts and profound consequences of dejure segregation on African Americans. De jure segregation, defined assegregation by racially explicit law andpolicy, is a complex system constructed over decades to perpetuate—and in some instances to initiate—thespatial separation of whites and Blacks.The Color of Law argues that this typeof residential segregation over thecourse of the twentieth century definedwhere whites and Blacks could live anddenied African Americans access tomiddle-class neighborhoods, with effects continuing to the present. Furthermore, Rothstein provocativelyholds that this governmental promotion of housing segregation—occurringat federal, state and local levels—represents a continuing violation of theU.S. Constitution’s Fifth, Thirteenthand Fourteenth Amendments. Finally,Rothstein agrees with past SupremeCourt precedent (e.g. Milliken v. Bradley, Parents Involved in CommunitySchools v. Seattle School District, etc.)that the enactment of legal constitutional remedies requires showing thatsegregation had governmental origins.However, whereas Court decisionsfound no evidence of such state involvement, Rothstein sets out in the(Please turn to page 2)CONTENTS:Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law . 1Brian Knudsen. A book review.Segregation: A Persistent Public Health Challenge . 3Robert Hahn. A major information gap for healthagencies needs a response.This Green and Pleasant Land . 5Bryan Greene. Harlem at a crossroads in the summer of ‘69.Essay: The Fight to be Public . 7Tyler Barbarin. Reimagining the Community BenefitsAgreement.PRRAC Update . 10Resources . 15Poverty & Race Research Action Council 1200 18th Street NW Suite 200 Washington, DC 20036202/906-8023 FAX: 202/842-2885 E-mail: info@prrac.org www.prrac.orgRecycled Paper

(COLOR OF LAW: Cont. from page 2)book to remove any doubt that suchacts took place. Constitutional remedies can be placed on the publicagenda, he contends, only after “wearouse in Americans an understandingof how we created a system of unconstitutional state-sponsored, de jure segregation, and a sense of outrage aboutit .”The core chapters of The Color ofLaw provide a descriptive historical account of de jure segregation. Rothsteinseparately discusses each element of dejure segregation, including government enforcement of racially restrictive covenants, the use of zoning ordinances for exclusionary purposes,segregation of public housing,redlining, and explicit racial requirements in the Federal HousingAdministration’s mortgage insuranceprogram. While these topics (and theothers included in the book) have beenfrequently treated separately in priorresearch, perhaps never before nowhave they been so accessibly joinedtogether in this way. This is an important innovation. Amassing all ofthis material together portrays in vividfashion how all-encompassing andmulti-varied were the governmentalefforts to spatially separate the races,and therefore to exclude Blacks fromequal participation in the society,economy and polity. We also learnfrom Rothstein’s research—so ablypresented in colorful examples and stories—that this diverse process playedout over many decades and in innumerable locations, both small andlarge. Overall, the reader leaves thebook moved and overwhelmed withthe knowledge of the magnitude andcreativity of past efforts to enforcehousing segregation in the UnitedStates.Moreover, The Color of Law is published at an opportune moment. Thatthis book appears in the midst of anemerging zeitgeist of race-consciousscholarship and activism is propitious,and Rothstein clearly intends to contribute to and build upon this newwork. Following authors such as TaNehisi Coates, Jeff Chang, KeeyangaYamahtta Taylor, and MichelleAlexander, Rothstein’s book demandsthat we explicitly and openly grapplewith race, with our society’s sordidhistory of past racial injustices, andwith the way that race continues to inform and shape our fraught contemporary moment. As Coates writes inThe Case for Reparations, an “Americathat asks what it owes its most vulnerable citizens is improved and humane.”Race continues toshape our fraughtcontemporary moment.Furthermore, all of these scholars(as well as activists such as the Movement for Black Lives) call us to putaside colorblind approaches to racialand social justice and to once againheed the words of Justice ThurgoodMarshall that “class-based discrimination against [Blacks]” necessitates“class-based remedies.” The Color ofLaw does all of this, but also makes anovel contribution by focusing raceconscious scholarship upon housing,whereas much of the contemporary literature has centered on criminal justice reform and mass incarceration.Several questions remain unanswered by the book, hopefully to betaken up by future researchers. First,Poverty & Race (ISSN 1075-3591) is published four times a year by the Poverty andRace Research Action Council, 1200 18th Street NW, Suite 200, Washington, DC 20036,202/906-8052, fax: 202/842-2885, E-mail: info@ prrac.org. Megan Haberle, editor;Tyler Barbarin, editorial assistant. Subscriptions are 25/year, 45/two years. Foreignpostage extra. Articles, article suggestions, letters and general comments are welcome,as are notices of publications, conferences, job openings, etc. for our Resources Section—email to resources@prrac.org. Articles generally may be reprinted, providing PRRACgives advance permission. Copyright 2017 by the Poverty and Race Research Action Council. All rightsreserved.2 Poverty & Race Vol. 26, No. 2 April-June 2017the book infers that contemporary patterns of segregation are directly andsingularly caused by governmental actsfrom decades prior. However, suchlinks between past and present need tobe more methodologically and analytically demonstrated than what can bediscerned from Rothstein’s historicaldescriptive account. Similarly,whereas The Color of Law pins all ofits explanatory weight to a single factor, complex phenomena—like residential segregation—are instead usually multi-causal. Future work shouldstrive to incorporate other causal elements into our understanding of presentpatterns and conditions, includingempirically modeling and measuringthe magnitudes of the relative contributions of different sets of factors.Furthermore, what explains de juresegregation? Was it a reflection of theracist sensibilities of the majority ofAmericans at the time? Or, was it elitedriven? For instance, on some occasions Rothstein draws attention to governmental responsiveness to the racistviews of the citizenry whereas elsewhere he suggests that governmentpolicies undid integrated communitiesin which Blacks and whites were coexisting. Finally, The Color of Lawomits any discussion of class and itsrelationship to race, racism and segregation. Is there any political-economicbasis for racism and/or segregative actsor are these expressions of attitudinaldeficiencies? Answers to these kindsof questions would merely build uponRothstein’s contribution, and help toflesh out even more our understanding of these relationships.The Poverty & Race Research Action Council has been exploring thehistorical roots of segregation for sometime, including in three Ford Foundation sponsored studies that trace the development of federal housing andtransportation policies in relation to increasing housing and school segregation in American metropolitan areas.(“Housing and School Segregation:Government Culpability, GovernmentRemedies” PRRAC 2004). The Colorof Law is a powerful addition to anhistorical understanding of governmental contributions to segregation.

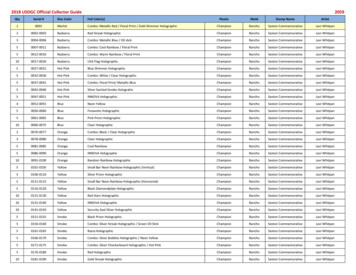

Racial and Ethnic Residential Segregationas a Root Social Determinant of Public Healthand Health Inequity: A Persistent Public HealthChallenge in the United StatesRobert A. HahnIntroduction.Segregation as aFundamental PublicHealth IssueThere is a great and urgent needfor public health practitioners to better understand the association of racialand ethnic segregation with ill-healthand to collaborate with other agenciesto address the underlying causes. Thisessay provides a synthesis of researchon health and segregation and proposescollaborative work between publichealth and other agencies to jointlyaddress this persistent problem.While some forms of residential andethnic residential segregation (RERS)can promote community and health(Cutler and Glaeser 1997; Fullilove2001), far too much RERS in theUnited States is the consequence ofpoverty and restricted choice and theroot of substantial poor health (Cutler, Glaeser et al. 1997). Yet, there isextensive evidence that federal, state,and local governments have been active participants in the promotion ofRERS at least since the end of Reconstruction (Rothstein 2017). We knowthat where a person lives is a majordeterminant of his or her health andwell-being because it affects exposureto both threats to and resources forhealth (Diez Roux 2001). Harmful local exposures may include pollutants,toxins, and pathogens as well as interpersonal and institutional racism, violence, and physical hazards (Williamsand Collins 2001; Reskin 2012). Local resources for health may includeRobert A Hahn, rahahn5@gmail.com, is an Adjunct Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology at Emory University.access to healthy food, water, sanitation, recreation, transportation andemployment, housing, the justice system, education, health care, and otherservices (Braveman and Gottlieb2014). This article summarizes themultiple, interrelated ways in whichRERS in the United States continues“ . . . Your longevity maybe more likely to beinfluenced by your zipcode than by yourgenetic code.”Frieden (2013)to harm minority populations; themagnitude, trends and sources ofRERS; public health burden of RERS;and opportunities for redressing public health harms in order to promotepublic health and health equity (Williams and Collins 2001; Kramer andHogue 2009).Measuring SegregationRacial and ethnic residential segregation (RERS) is “the isolation of poorand/or racial minorities that live incommunities and neighborhoods separated from those of other socioeconomic groups” (Li, Campbell et al.2013). There are multiple dimensionsof segregation—evenness, exposure,concentration, centralization, and clustering—each with a specific statisticaldefinition (Massey, White et al.1996); when a population in an areahas high levels on several dimensions,it is said to be “hypersegregated” andmay suffer multiple forms of deprivation (Massey and Tannen 2015).The most common measure of RERSis the “dissimilarity index”—the proportion of comparison racial and ethnic populations that would have toswitch regions in order to make proportions equal in both regions. The dissimilarity index varies from 0 (identical proportions of each population inboth regions, i.e., no residential segregation) to 100 (all of one populationin one geographic region, all of theother population in the second region,i.e., total residential segregation)(Massey and Denton 1988). Dissimilarity rates of 30–60 are consideredmoderate, rates 60 are consideredhigh. Another common measure, “exposure,” is the likelihood that a member of one group encounters a member of the other group. Exposure is amatter of the relative proportions ofeach group in the regions rather thanthe evenness of their distribution acrossregions (Massey, White et al. 1996).Segregation as a SocialDeterminant of HealthSegregation is associated with public health harm and inequity throughseveral pathways (Figure 1, p. 6).While the multiple associations ofRERS with factors related to poorhealth are described separately, thesefactors likely interact and compoundeach other in a system (Reskin 2012)that reinforces and perpetuates segregation itself in a feedback loop.a. Environment and sanitation:Minority and segregated communitiesare commonly located closer to sourcesof environmental toxic exposures thanother communities (Lopez 2002;Mohai and Saha 2007; Jacobs 2011).b. Safety: Violent crime not onlyharms the local population physically,(Please turn to page 4)Poverty & Race Vol. 26, No. 2 April-June 2017 3

(HEALTH: Continued. from page 3)but also instills fear and may deter social interaction and physical activity(Gordon-Larsen, McMurray et al.2000).c. Housing: Housing is a basic human need that provides shelter and,with home ownership, investment andsecurity. Overall, Black home ownership in the United States is 25% lowerthan that of whites and the gap increased slightly from 1970 to 2001;trends are similar for all income levels except those with the highest income in which the gap decreased from13.9% to 11.9% during this period(Herbert 2005). In addition, moreBlacks and Hispanics live in crowdedand lower quality housing (with problems of heating, plumbing, etc.)which contributes to poor mental andphysical health (Changing America;Evans and Saegert 2000; Jacobs 2011).d. Transportation: Transportationprovides passage to employment andother resources and may also be asource of pollution and injury. Publictransportation resources for low-income and minority communities areoften inadequate (Sanchez, Stolz et al.2003). Nevertheless, greater proportions of minority populations rely onpublic transportation than do whites,and minority populations spend greaterproportions of their incomes on transportation (Bureau of TransportationStatistics 2003).e. Employment: The residential segregation of Blacks and Hispanics is associated with diminished employmentopportunities, lower wages, and theirmultiple health consequences, a phenomenon referred to as “spatial mismatch,” i.e., the spatial separation ofresidence and employment opportunities (Turner 2008).f. Cost of living: For the same quality goods, residents in low-income andsegregated neighborhoods pay morethan those living outside of such neighborhoods, an excess referred to as the“poverty” or “ghetto tax” (Karger2007; Pager and Shepherd 2008).g. Education: The segregation ofminority communities is associatedwith lower quality schooling (Ong andRickles 2004; Bohrnstedt 2015), withsubstantial long term health consequences (Johnson 2011; Hahn andTruman 2015). It is estimated that thecognitive skills of children whose families have lived in poor neighborhoodsfor two generations are diminished bythe equivalent of between two and fouryears of schooling(Sharkey 2013).h. Nutrition, alcohol, and substanceabuse: Segregated neighborhoods often have reduced access to full-service,relatively less expensive supermarkets(Powell, Slater et al. 2007), high concentrations of fast-food and less nutritious food (Powell, Chaloupka et al.2007), and higher densities of alcoholoutlets (Powell, Slater et al. 2007).These conditions are associated withobesity (Corral, Landrine et al. 2011)and higher rates of alcohol- and drugrelated harms (Campbell, Hahn et al.2009).i. Health Care: Residential segregation is also associated with reducedaccess to health care services(Smedley, Stith et al. 2003; White,Haas et al. 2012) and lower utilization (Gaskin, Dinwiddie et al. 2011).While access and utilization havegreatly increased with the AffordableCare Act (Long, Kenney et al. 2014),(Please turn to page 10)Figure 1. How Racial and Ethnic Residential Segregation Harms Well-Beingand Promotes Health Inequity4 Poverty & Race Vol. 26, No. 2 April-June 2017

Parks and RecreationBryan GreeneWhen people first hear about the1969 Harlem Cultural Festival, theyask, "Why isn't there a movie?"The New York Times reported thatthe festival drew 300,000 to six Sunday concerts in Harlem's Mount Morris Park the summer of 1969. It boastedsome of the biggest names in popularmusic—The Fifth Dimension, Sly andthe Family Stone, Stevie Wonder, TheStaple Singers, Nina Simone, B.B.King—but it is virtually unknown. Unlike "Woodstock," the same summer,and "Gimme Shelter," the film of theRolling Stones' 1969 tour, there is nosimilar film of the Harlem CulturalFestival, despite the pivotal momentit represents in Black music, politics,and culture. While two television networks aired one-hour specials withfestival highlights, the broadcasts leftlittle lasting impact on the culture. HalTulchin, a TV producer whose crewfilmed over 50 hours of the festival,reported that he was unable to interestanyone in a bigger project. As a consequence, the Festival remains, asdocumentary filmmaker JessicaEdwards calls it, "The most popularmusic festival you've never heard of."Someday, someone will make a filmabout the Festival, which marks its50th anniversary in two years. Thatfilmmaker will have to obtain therights to the concert footage that exists. Past efforts have proven unsuccessful. Many of the organizers andperformers have died in the intervening years. To piece things together, Ihave consulted newspaper and magazine accounts, watched the footage Icould obtain, and interviewed Festival attendees and performers. May thisarticle serve as the starting point forthe filmmaker who takes on thisproject. This is my treatment for thefilm that will come.Bryan Greene (greenebee@gmail.com) is a civil rights practitioner living in Washington, DC.Just as "Woodstock" and "GimmeShelter" use aerial shots to show themultitudes at those concerts, my filmof the Harlem Festival opens with ahelicopter over Mount Morris Park.This would be two years before the1969 Festival. Sitting in the helicopter are two Yale men—one, the Mayorof New York City, John Lindsay, theother, August Heckscher, his newly-The most popularmusic festival you’venever heard of.appointed Parks Commissioner (note:They are now deceased. We will haveto re-enact this). The men share a vision: to attract more New Yorkers tothe parks, especially Blacks and Hispanics. It's March 1967, and MayorLindsay, a Republican, is swearing inHeckscher.Heckscher describes the helicopterdescent into the Harlem park in his1974 memoir, Alive in the City:The mayor and I arrived at theceremony by helicopter, landingupon the summit of Mount Morris,a six-acre park situated at the center of Harlem. It seemed appropriate at that time to give emphasis toa black community. .As our helicopter came low I could see crowdsof children climbing up the slopesand steep paths to greet the mayor.This was a period when JohnLindsay's popularity was at itsheight, and he was a hero to youngblacks.Heckscher was New York aristocracy. His predecessor as Park Commissioner, the legendary RobertMoses, had named a Long Island statepark and Central Park's largest playground after Heckscher's grandfatherand namesake, a German-born capitalist and philanthropist. Heckscher'scommitment to improve park accessfor underprivileged New Yorkers stoodin stark contrast with Moses, whosebiographer, Robert Caro, told the NewYork Times, "[Moses] was the mostracist person I ever met." Caro, in hisPulitzer-prize winning biography ofMoses, described Moses's idea ofhelping Harlem residents feel at homein Riverside Park: he installedwrought-iron trellises with monkeyson the comfort stations.Heckscher, meanwhile, sponsoredthe Harlem Cultural Festival. In a pressrelease, Heckscher announced that theCity had partnered with MaxwellHouse, the General Foods subsidiary,to sponsor the 1969 Festival. Hestressed: "However, the City is not running the Festival; General Foods is notrunning it. We are only supporting it.The Harlem Cultural Festival belongsto Harlem. It is the expression of themany elements—‘soul,’ if you will—of the diverse cultures that make upthe Harlem community."Tony Lawrence, a Caribbean-bornsinger and actor, was the driving forcebehind the Festival. By 1969, the budget for the three-year old Festival hadgrown such that Lawrence told the NewYork Times, "The entertainers chargedme top price, and we paid it." Moreover, he said, "We put a lot of moneyaround this community. I hired asmany people as possible." This included money for security, advertising, and a house band. Lawrence alsoemphasized that the television crewsincluded Black supervisors and trainees. The Times said the Festival "provided a lucrative market for enterprising small merchants.to indulge inwhat Harlemites would call a 'legitimate hustle.'"The headliner the first day (whichthe Times said drew 60,000) was TheFifth Dimension. The group's record,"Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In," fromthe Broadway musical, Hair, was stillin the Billboard Top 40, after sixweeks at #1 in April and May."Aquarius" would win "Record of theYear" at the Grammy Awards (just as(Please turn to page 6)Poverty & Race Vol. 26, No. 2 April-June 2017 5

(PARKS: Continued from page 5)"Up, Up, and Away" had in 1968).The band's schedule was so packed thatit's no surprise the group's foundingmember, Lamonte McLemore, toldme he scarcely remembers the Harlemgig. They played Ed Sullivan that year.The group had just come off a tourwith Frank Sinatra, the only group togo on the road with him, McLemoresaid. They also guest-starred inSinatra’s 1968 TV special and openedfor him during his engagement in LasVegas. The group was ubiquitous. Weknow the group played the HarlemFestival because CBS-TV aired highlights of their performance in aprimetime special on July 28th. Alas,the concert footage remains in a vault.Meanwhile, Sly and the FamilyStone's 42-minute set is on the Internet(with Hal Tulchin's watermark). Theband is absent from posters, whichsuggests their July 27th performancewas a fortuitous last-minute booking;they played the popular Schaefer Music Festival in Central Park the daybefore.Sly and the Family Stone deliveran exhilarating performance. Tulchin'sfootage is in brilliant color, shot bymultiple cameras, and masterfully edited. The band’s setlist is almost identical to their Woodstock show twoweeks later. But the Harlem performance packs more punch: it's an historical moment to see the band, sporting Afros, bell-bottoms, and frilledjackets, play to tens of thousands inHarlem. If such a performance hadn'texisted, you'd have to invent it. Youcan imagine an inspired Larry Grahaminventing his trademark slap-bass technique, on the spot, inspired by theappreciative crowd. You see here howthe band had soaked up that time'scrosscurrent of music genres—rock,psychedelia, funk, soul—and taken itto a new level. The hippie zeitgeist ishere, too. When Sly sings, "Higher"he tells the crowd, "When we say'higher,' if you'd say 'higher' andthrow the peace sign up, we'd appreciate it. Now it don't make you mellow if you don't, it don't make yougroovy if you do." But the crowddoes. The song's breakdown is one ofthe most joyful music moments onfilm. See if it doesn't make you jumpup and dance. And when trumpetplayer Cynthia Robinson introduces"Dance to the Music," and shouts, "Getup and dance to the music! Get on upand dance to the music!" you wonderif the revolution might very well betelevised.The Festival provided a nationalshowcase for Black gospel music. Astaple on radio and local TV, gospeltook a leap forward when ABC-TVbroadcast, in primetime, highlightsfrom the Festival's "Folk and Gospel"concert on September 16, 1969. Helping whet the worldwide appetite forGospel took a leap forward when ABC-TVbroadcast highlightsfrom the Festival’s“Folk and Gospel” concert.Black gospel music was a breakout hitthat summer—an arrangement of anold hymn by an Oakland, Californiachoirmaster, Edwin Hawkins. "OhHappy Day" spent 10 weeks on theBillboard Hot 100, peaking at #4 onJune 7, 1969. It reached #1 in France,Germany, and the Netherlands. Whenthe Edwin Hawkins Singers took thestage June 29th in Mount Morris Park,they were one of the most popular actsin the world. CBS featured the Singers on the same July 28th special withthe Fifth Dimension.Edwin Hawkins told me in anemail:That was a whirlwind year for me.We'd recorded "Oh Happy Day" toraise money for our youth choirtour. It was as simple as that. A SanFrancisco radio station started playing it, and next thing you know,500 copies weren't enough. My calling is to spread the gospel, the goodnews. This song could have stayedin the church—which is what thechurch elders preferred when thesong showed up on the radio. But6 Poverty & Race Vol. 26, No. 2 April-June 2017the funny thing about gospel is ittouches people and it spreads. Youcan't contain it, and why wouldyou? I count myself so blessed tohave been a vehicle for this messagethat went around the world thatyear."Oh Happy Day" shaped gospelmusic for years to come but its influence went beyond that. GeorgeHarrison became the first formerBeatle to write a number-one song with"My Sweet Lord" in 1971. RonnieMack sued him successfully for copyright infringement, citing similaritieswith "He's So Fine," which Mack hadwritten for the Chiffons. GeorgeHarrison in his 1980 autobiography,"I, Me, Mine," demurred. He said,"I was inspired by the Edwin HawkinsSingers' version of 'Oh Happy Day.'"While Hawkins was a 26-year oldnewcomer in 1969, Mahalia Jacksonwas the reigning "Queen of Gospel."She had inherited the mantle from hermentor, composer Thomas A. Dorsey.Jackson would perform with her protege Mavis Staples at the festival, amoment Jessica Edwards, maker of thefilm "Mavis!" said "very much indicated a passing of the baton." Together, Jackson and Staples sangDorsey's standard, "Take My Hand,Precious Lord," which Jackson sangat the funeral of Dr. Martin LutherKing, Jr. The crowd, many in theirSunday best, responded enthusiastically. Exiting the stage, Jackson andStaples passed the mike to their mutual Chicago friend, civil-rights leaderJesse Jackson.The footage I saw of the Festival'sgospel concert is not publicly available, but Mahalia Jackson's appearance at the concert is more widelydocumented by a New York Times photograph of her with Mayor Lindsay,on the steps of her trailer. Lindsay wasin Harlem, campaigning for re-election. Jackson, with her arm aroundLindsay, told the assembled reporters,"We're really going to go for him."Accounts of the Festival say the emcee introduced Lindsay to the crowdthat day as "our blue-eyed soulbrother."(Please turn to page 8)

EssayThe Fight to be Public: Making Public SpacesAccessible to AllTyler BarbarinAn Emerging NationalDiscussionThe public sphere is often the mostcontentious space in our lives, butsometimes the least examined. Whatis a public space? Is there an affirmative right to access public space and ifso, what is that right? How do we navigate situations of conflict in publicspaces? How do we mitigate fear anddiscomfort during interactions? Thestranger that lingers too long, the bodythat stands in the shadows, the groupthat feels just too big or too loud—what are reasonable expectations ofsafety, comfort and certainty? Aresuch expectations guaranteed and towhom does the guarantee run? Toooften we see the mitigation of fear turninto the over-policing of Black,Brown, trans and disabled bodies. Thisfear manifests itself in the regulationand oppression of sexual orientationsand expressions that fall outside of thenorms of the dominant culture. Acrossthe country public spaces have beenthe site of abuses of power by the powerful, the control of the minoritized,and the perpetuation of damaging systems of oppression.In American society, there is an assumption of neutrality in unnamed,unregulated spaces. This assumptioncreates a false comfort. America’s history of oppression and regulation ofbodies has prevented this assumed neutrality from actualizing. Spaces thatare not intentionally integrated andmade to be safe for the unique andspecific needs of historically minorTyler Barbarin, tbarbarin@prrac.org, is Administrative and ResearchAssistant at PRRAC. This essay is anexcerpt from a longer work under development.itized groups become inherently dangerous spaces. The consequence of allowing our public spaces to be inhabited, monitored and controlled underthe guise of being free from labels,rules or constraints is that these spacesdefault to regulation by stereotypes,misconceptions and prejudice. Thosewho are not white, male, heteronormative and able-bodied often become subject to policing based on thecomforts of the majority. Instances ofharassment, policing and altercationsleading to the mistreatment and evenUse of public spacesshapes our sense ofbelonging and, therefore, affects our role inthe social order.death of minoritized people have become all too frequent. Those that inhabit multiply oppressed intersectionalidentities, such as Black trans women,trans wo

book moved and overwhelmed with the knowledge of the magnitude and creativity of past efforts to enforce housing segregation in the United States. Moreover, The Color of Law is pub-lished at an opportune moment. That this book appears in the midst of an emerging zeitgeist