Transcription

k aic osmemri s s i o nonmedicaidand theuninsuredELIMINATING ADULT DENTAL COVERAGE IN MEDICAID:AN ANALYSIS OF THE MASSACHUSETTS EXPERIENCEPrepared byCarol Pryor, MPH, EdMThe Access ProjectandMichael Monopoli, DMD, MPH, MSDelta Dental of MassachusettsSeptember 2005

k aic osmemri s s i o nmedicaidand theuninsuredThe Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and theUninsured provides information and analysison health care coverage and access for thelow-income population, with a special focuso n M e d i c a i d ’s r o l e a n d c o v e r a g e o f t h euninsured. Begun in 1991 and based in theK a i s e r F a m i l y F o u n d a t i o n ’s Wa s h i n g t o n , D Coffice, the Commission is the largestoperating program of the Foundation. TheC o m m i s s i o n ’s w o r k i s c o n d u c t e d b yFoundation staff under the guidance of a bipartisan group of national leaders ande x p e r t s i n h e a l t h c a r e a n d p u b l i c p o l i c y.JamesR.Ta l l o nChairmanDianeRowland,ExecutiveSc.D.Director

k aic osmemri s s i o nonmedicaidand theuninsuredELIMINATING ADULT DENTAL COVERAGE IN MEDICAID:AN ANALYSIS OF THE MASSACHUSETTS EXPERIENCEPrepared byCarol Pryor, MPH, EdMThe Access ProjectandMichael Monopoli, DMD, MPH, MSDelta Dental of MassachusettsSeptember 2005

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThe authors of this paper wish to acknowledge the many individuals who assisted with thisproject; without their help, this research could not have been completed. Most of all we wouldlike to thank all of the dental providers and program administrators who agreed to beinterviewed, and the MassHealth enrollees who participated in the focus groups and shared theirexperiences about losing dental coverage and trying to access dental care. Nancy Kohn, fieldcoordinator of The Access Project, organized and facilitated focus groups with MassHealthenrollees. Ellen Campbell at the Greenfield Housing Authority recruited participants andprovided space for the focus group in Western Massachusetts on very short notice. Stacey Augerof the Oral Health Task Force in Massachusetts offered advice and support. GeorgiosKontovazainitis, D.D.S., provided administrative and research support. Caroline Washburn,Beth Perry, and Richard Fitzmaurice at the Massachusetts Division of Health Care Finance andPolicy answered innumerable questions about administration of the Uncompensated Care Pool,and about claims and reimbursement data. Dr. Mahyar Mofidi of the University of NorthCarolina shared materials from his focus groups with Medicaid enrollees on barriers to obtainingdental care. Finally, the authors would like to thank the Kaiser Family Foundation for fundingthis project and Samantha Artiga and Barbara Lyons at the Kaiser Family Foundation for theirsupport and assistance.

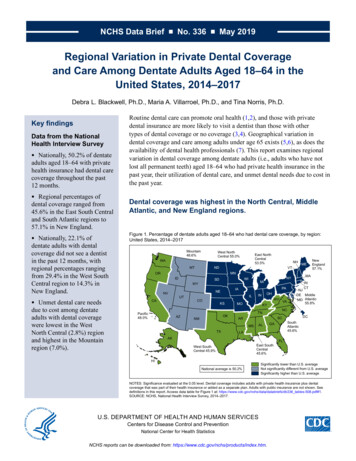

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYResearch has increasingly highlighted the importance of oral health and the interrelationship oforal health and overall health. A 2000 Surgeon General’s report noted the importance of oralexaminations for detecting early signs of nutritional deficiencies and systemic disease andpointed to emerging associations between oral health and conditions such as diabetes, heartdisease, stroke, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Lack of dental insurance is a major barrier toobtaining oral health care and, as noted in the Surgeon General’s report, “accounts in part for thegenerally poorer oral health of those who live at or near the poverty line.”Historically, adult dental coverage has been one of the first areas states have turned to whenmaking Medicaid reductions. As states faced significant budget shortfalls in recent years, anumber reduced Medicaid benefits, including adult dental services. In March 2002,Massachusetts reduced coverage for a number of benefits in its Medicaid program, MassHealth,including most dental services for adults. The state made further adult dental coveragereductions in January 2003. MassHealth adult enrollees lost coverage for preventive dentalservices, such as dental cleanings and periodic exams; periodontal treatment for gum disease;and restorative treatments such as fillings, root canals, and crowns. While tooth extractions arestill covered by MassHealth, dentures to replace missing teeth are not.This report examines the impact of the MassHealth dental coverage reductions. It is based oninformation collected between September 2004 and June 2005 through structured interviewswith thirteen dental providers in the state, two focus groups with current MassHealth enrolleeswho had dental care needs, and an analysis of state administrative data.FindingsIn FY2004, 100,000 fewer MassHealth adult enrollees received dental services reimbursedby MassHealth than in FY2001, the year prior to the reductions (Figure 1). The proportionof adult MassHealth enrollees who received dental services reimbursed by MassHealth declinedfrom 24 percent in FY2001 to 11 percent in FY2004. During FY2001, over 693,000 adults werecovered by MassHealth, of whom slightly fewer than 168,000 received dental services paid forby the program. In FY2004, MassHealth covered just over 640,000 adults, of whom about68,000 received dental services reimbursedby MassHealth. Adults covered byPercent of Adult MassHealth EnrolleesMassHealth include parents of children onReceiving Dental ServicesMassHealth with incomes up to 133 percentof the federal poverty level (FPL);24%24%unemployed adults with incomes up to 100percent of the FPL; and pregnant women,11%disabled adults, people with HIV, and10%employees of certain employers withincomes up to 200 percent of FPL. In2005, the FPL was 9,570 per year for aNumber ThatFY2001FY2002FY2003FY2004Receivedsingle adult and 19,350 per year for a167,799168,85763,39067,988DentalServicesfamily of four.Figure 1SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of Massachusetts’ Medicaid ManagementInformation System data.K A I S E RC O M M I S S I O NO NMedicaid and the Uninsured1

Following the benefit reductions, private dentists experienced a marked decline inMassHealth reimbursements. The major providers of dental care for MassHealth enrollees areprivate dentists, who accounted for approximately 90 percent of total MassHealth dentalreimbursements prior to the benefit reductions. Overall, private dentists experienced a 14percent decline in MassHealth reimbursements between FY2001 and FY2004. The privatedentists interviewed for this report said they offered MassHealth patients discounted prices forservices following the benefit reductions; however, they reported that these patients could notafford care even at the discounted rates. To maintain revenues, some private dentists focused onincreasing their volume of privately insured patients.The number of private dentists actively treating MassHealth patients declined after thereductions. MassHealth enrollees faced significant barriers to obtaining dental care prior to thedental benefit reductions because of a lack of dental providers who accepted MassHealth.Following the benefit reductions, the number of dentists accepting MassHealth patients declinedFigure 2even further. Of the approximately 5,000practicing private dentists inNumber of Private Dentists Who Received atMassachusetts, about 795 receivedLeast 5,000 in MassHealth Reimbursementsreimbursements from MassHealth of at795794least 5,000 in FY2001, the year prior to742the dental coverage reductions. Thisnumber fell by 15 percent to 678 in678FY2004 (Figure 2). Further, theavailability of dentists participating inMassHealth varied across the state, withover half (55 percent) of cities and townsFY2001FY2002FY2003FY2004in Massachusetts lacking a participatingdentist and rural areas experiencing theMedicaid and the Uninsuredmost significant participation problems.NOTE: 5,000 in annual billing is considered a conservative threshold for identifyingdentists actively seeing MassHealth patients. As of 1996, dentists who billed 5,000averaged 14 MassHealth patients per year; given increases in fees since 1996, thatnumber is likely fewer today.SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of Massachusetts’ Medicaid Management InformationSystem data.K A I S E RC O M M I S S I O NO NDental directors at community health centers (CHCs) indicated that they did not have thecapacity to deal with large numbers of new patients. Massachusetts currently has 37 CHCsthat offer dental services, some at multiple sites. While the CHCs are an important source ofcare for MassHealth enrollees, they historically have provided only a small portion of theirdental care. Unlike private dentists and dental schools, CHCs are able to receive reimbursementsfor dental services from the state’s Uncompensated Care Pool, which reimburses acute carehospitals and CHCs for a portion of the uncompensated care they provide to income-eligibleuninsured and underinsured patients. After the MassHealth dental benefit reductions, the CHCswere able to receive reimbursement from the Pool for dental services provided to MassHealthpatients. The CHCs thus became one of the few sites where MassHealth enrollees couldcontinue to receive most dental services at no cost.Interviews with CHC dental directors suggest that prior to theMassHealth dental coverage reductions, the dental clinics faced ahigh level of demand for services. Thus, they did not have thecapacity to meet the increased need following the benefitreductions. The dental directors reported long waits for2“There are probably 80,000people [in our area] waitingfor 10,000 appointments.”-Dental director at a community healthcenter

appointments, in some cases up to four and five months, and long waiting lists, sometimes up to1,000 people; some CHCs stopped accepting new patients altogether. Further, some directorsreported making changes in operations that may have made it more difficult for patients to accesscare. For example, some reported reducing staff and the number of operating sessions; othersbegan requiring up-front deposits from patients for complex procedures and out-of-pocketpayment of the costs of making dentures, which are not reimbursed by the Pool.Focus group respondents and providers reported that MassHealth enrollees experienced anincrease in untreated dental problems and a reduction in corrective and restorativetreatments. Almost all focus group respondents said they were living with ongoing, seriouspain from untreated dental problems. They reported that they could not afford treatment, andmany said their only option was extraction of teeth, since this“They wanted to take out twoservice is still covered by MassHealth. A number said they lostfront teeth. I fought so hardteeth that could have been saved through treatment; others saidfor those teeth because theythey were living with pain to avoid losing their teeth. For some,were in front. I went throughpain.”dental problems exacerbated other chronic or disabling conditions,-MassHealth enrolleeand many said they experienced gastric and nutritional problemsbecause they could not chew their food properly.These problems were echoed in the interviews with dentalproviders. Dental school directors reported that they wereproviding fewer complex procedures and less comprehensivetreatment because patients could not afford the fees. Privatedentists said they were providing fewer restorative services, morefrequently extracting teeth that could have been saved withappropriate treatment, and conducting more extractions on anemergency basis to relieve pain, while fitting many fewerMassHealth enrollees with dentures.MassHealth enrollees described living with pain, diminishedself-esteem, and negative effects on employment and theirfamilies’ finances due to dental problems. Many focus groupparticipants said they lived with continuous pain rather than havingtheir teeth extracted because they feared not only the physical, butalso the social consequences of being toothless. Severalrespondents commented that they felt having bad teeth diminishedtheir self-image and sense of self worth. Many also feared thattoothlessness would limit their ability to find employment; somenoted that they were not confident about applying for jobs becauseof their appearance. Focus group respondents also said they facedfinancial hardships due to the cost of dental care. Those whoobtained care found it very difficult to pay for it and often had toborrow money from relatives or forgo other needed purchases topay dental care costs.“[the inability to fit people withdentures is] devastating,especially because manyMassHealth patients areelderly. Dentures areessential for nutrition-if peopledon’t have teeth, they can’tchew or eat as well.”-Private dentist“I’ve had opportunities toapply for jobs. I didn’t feel likeI had the self-esteem becauseit had to do with customerservice, because I needorthodontic and dental care. Ido not feel as comfortablesmiling. I didn’t feel like Iwould get hired They needsomebody who can smile andlook pretty to the customers.”-MassHealth enrollee“ you have to do thejuggling. The juggling is doyou not pay your rent? Doyou not take your medication?What sacrifices do you haveto do?.It is tough. It is reallytough.”-MassHealth enrollee3

The dental benefit reductions resulted in savings of less than one percent of the state’sshare of total program spending, and it appears that some dental costs were shifted to otherareas. MassHealth reimbursements for adult dental services in FY2004 were about 35 millionless than in FY2001, the year prior to the reductions. After deducting the foregone federalmatching funds, state savings would be 16.5 million in FY2004. This represents less than onepercent of the state’s share of total MassHealth spending, which was just under 3 billion inFY2004. Further, it appears that some dental costs were shifted to other areas, including thestate’s Uncompensated Care Pool.ConclusionAlthough research has increasingly recognized the importance of dental care and coverage foroverall health and well-being, adult dental benefits are often one of the first targets of Medicaidreductions. The experience in Massachusetts highlights the importance of Medicaid dentalcoverage for both individuals and providers. MassHealth enrollees who lost dental coveragefaced significant barriers to obtaining needed dental care, largely due to cost and lack of capacityamong dental safety net providers. Many enrollees endured serious pain due to untreated dentalconditions, which in some cases exacerbated other chronic or disabling health conditions.Providers’ care was compromised by MassHealth enrollees’ lack of coverage, and it appearssome private dentists stopped serving MassHealth patients altogether. Overall, the state achievedminimal savings from the benefit reduction compared to overall program spending, and somecosts have been shifted to other areas, including the state’s Uncompensated Care Pool.4

I. INTRODUCTIONResearch has increasingly highlighted the importance of oral health, the interrelationship of oralhealth and general health, and persistent problems of access to dental care, especially amonglow-income populations. In 2000, the Surgeon General released a comprehensive report on oralhealth, which highlighted the importance of oral examinations in detecting early signs ofnutritional deficiencies and systemic diseases.1 It emphasized that the mouth is a point of entryfor infections that can spread to other parts of the body2 and pointed to emerging associationsbetween oral diseases and other physical ailments, such as diabetes, heart disease, stroke, andadverse pregnancy outcomes, such as low birth weight babies. The report also discussed thecontribution of oral-facial pain to a diminished quality of life and the relationship between facialdisfigurements due to oral disease and social stigma, loss of self-esteem, and anxiety, which mayin turn limit educational, career and marriage opportunities. The report identified lack of dentalinsurance as a major barrier to obtaining oral health care, one which “accounts in part for thegenerally poorer oral health of those who live at or near the poverty line.”3The Massachusetts Medicaid program, MassHealth, included dental benefits for adults until thebeginning of 2002. However, faced with a recession and budget deficits, the state eliminatedmany optional Medicaid benefits, including most dental benefits for adults. This reportexamines the impact of eliminating most dental benefits for adults enrolled in MassHealth ondental providers, MassHealth enrollees, and state spending. It is based on interviews with dentalproviders, focus groups with enrollees who needed dental care following the reductions, and ananalysis of state administrative data.II. BACKGROUNDMassHealth provides coverage to low-income children and families, pregnant women, long-termunemployed adults, seniors, and persons with disabilities. Generally speaking, eligible adultsinclude parents of children on MassHealth with incomes up to 133 percent of the federal povertylevel (FPL); unemployed adults with incomes up to 100 percent of the FPL; and pregnantwomen, disabled adults, people with HIV, and employees of certain employers with incomes upto 200 percent of FPL. (Low-income non-disabled adults have limited access to the program.)4In 2005, the FPL was 9,570 per year for a single adult and 19,350 per year for a family of four.MassHealth included dental benefits for adults until the beginning of 2002. However, faced witha recession and budget deficits, the state eliminated many optional Medicaid benefits including,in March 2002, most dental benefits for adults. This was followed by a further limitation ofadult dental benefits in January 2003. MassHealth adult enrollees lost coverage for preventiveservices, such as dental cleanings and periodic exams; periodontal treatment for gum disease;and restorative treatments such as fillings, root canals, and crowns. While tooth extractions1U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General,National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, 2000.2According to the Forsyth Institute, a research institute that focuses on oral health, “if protecting health is largely amatter of protecting the body from destructive invaders, then the mouth is the body’s unguarded gate.”3U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, op.cit., p. 12.4R. Seifert, The Basics of MassHealth, the Medicaid Program in Massachusetts, Massachusetts Medicaid PolicyInstitute, December 2004.5

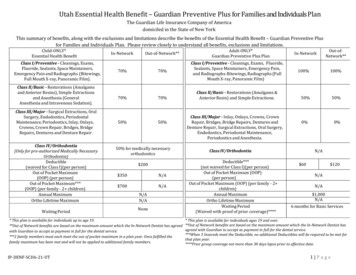

remain covered by MassHealth, dentures to replace missing teeth are not.5 These changespotentially affected over a half million people–during the year ending in June of 2002, almost700,000 adults were covered by the program. The state anticipated achieving combined federaland state savings of about 30 million annually by eliminating the adult dental benefits.Table 1: Changes in Dental Coverage for Adult MassHealth EnrolleesChange in CoverageAdults AffectedServiceCovered Prior toReductionParents 133% FPLExams Unemployed adults 100% FPLCleanings Pregnant women 200% FPLX-rays Disabled adults 200% FPLFillings People with HIV 200% FPLLimited treatment for gum disease Crowns & root canals on front teeth Extractions & oral surgery Dentures OtherCovered AfterReduction Emergency treatment toreduce painServices for enrolleesw/special circumstancesdesignationThe state created one exception to the elimination of MassHealth adult dental benefits. Adultswho were either so severely disabled that they could not maintain oral hygiene or those forwhom dental disease and resulting infections were potentially life threatening could apply forspecial circumstances designation, which allowed them to maintain dental coverage. To applyfor the designation, patients must have their primary care provider send a letter to their dentistverifying that they meet the criteria, and the dentist must then submit the letter to MassHealth.According to MassHealth officials, approximately 20,000 people have

dental benefit reductions because of a lack of dental providers who accepted MassHealth. Following the benefit reductions, the number of dentists accepting