Transcription

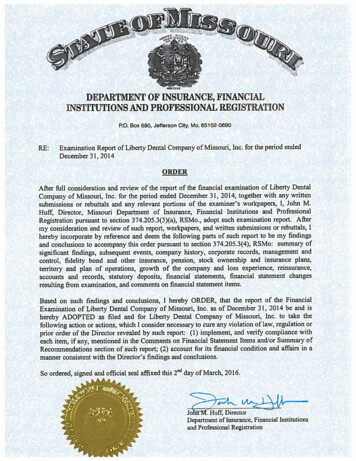

For a New LibertyThe Libertarian ManifestoRevised Editionby Murray N. RothbardCollier BooksA Division of Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc.New YorkCollier Macmillan PublishersLondonOnline edition prepared by William Harshbarger.Cover by Chad Parish.Ludwig von Mises Institute 2002.

Copyright 1973, 1978 by Murray N. RothbardAll rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmittedin any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, includingphotocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc.866 Third Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10022Collier Macmillan Canada, Ltd.Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication DataRothbard, Murray Newton, 1926—For a new liberty.Includes bibliographical references and index.1. Liberty. 2. Laissez- faire. 3. United States—Economic policy. 4. United States—Social policy.I. Title.JC 599 .U5 R66 1978320.5’I’097378–12225ISBN 0–02–074690–3Printed in the United States of AmericaFor a New Liberty, in its original version, is available in a hardcoveredition from Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc.First Collier Books Edition 1978

TO JOEY,still the indispensable framework

Table of ContentsPreface.viThe Libertarian Heritage: The American Revolution and ClassicalLiberalism . 1The Libertarian Creed . 21Property and Exchange . 22The State . 45Libertarian Applications to Current Problems . 71The Problems . 72Involuntary Servitude. 78Personal Liberty. 93Education . 119Welfare and the Welfare State . 143Inflation and the Business Cycle: The Collapse of the KeynesianParadigm . 174The Public Sector, I: Government in Business . 198The Public Sector, II: Streets and Roads . 205The Public Sector, III: Police, Law, and the Courts . 219Conservation, Ecology, and Growth. 247War and Foreign Policy . 269Epilogue . 303A Strategy for Liberty. 304Index. 330

PrefaceWHEN THE ORIGINAL EDITION of this book was published (1973),the new libertarian movement in America was in its infancy. In half adozen years the movement has matured with amazing rapidity, and has expanded greatly both in quantity and quality. Hence, while the discussion oflibertarianism in this book has been strengthened and updated throughout,the greatest change is in our treatment of the libertarian movement. Theoriginal chapter I, on “The New Libertarian Move ment,” is now irrelevantand outdated, and it has been transformed into an appendix providing anannotated outline of the complex structure of the current movement. Thenew chapter I, on “The Libertarian Heritage,” provides a brief but badlyneeded historical background of the American and Western tradition ofliberty, and of its successes and failures, setting the stage for ourdiscussion of its rebirth in today’s movement. A new chapter 9 has beenadded on the vital topic of inflation and the business cycle, and the roles ofgovernment and of the free market in creating or alleviating these evils.Finally, to the concluding chapter on strategy has been added apresentation and explanation of my recently gained conviction that libertywill win, that liberty will be making great strides immediately as well as inthe long run, that, in short, liberty is an idea whose time has come.I owe the origin and inspiration of this book to my first editor, TomMandel, who had the vision to anticipate the recent enormous growth ofinterest in libertarianism. The book would neither have been conceivednor written without him. For the revised edition, Roy A. Childs, Jr., editorof Libertarian Review, was extremely helpful in suggesting neededchanges. I would also like to thank Dominic T. Armentano, of theeconomics department of the University of Hartford, Williamson M.

PrefaceviiEvers, editor of Inquiry, and Leonard P. Liggio, editor of The Literature ofLiberty, for their welcome suggestions. Walter C. Mickleburgh’s unbounded enthusiasm for this book was vitally important in preparing therevised edition; and Edward H. Crane III, president of Cato Institute, SanFrancisco, was indispensable in providing help, encouragement, soundadvice, and suggestions for improvement.MURRAY N. ROTHBARDPalo Alto, CaliforniaFebruary 1978

For a New Liberty

1The Libertarian Heritage: The AmericanRevolution and Classical LiberalismON ELECTION DAY, 1976, the Libertarian party presidential ticket ofRoger L. MacBride for President and David P. Bergland for VicePresident amassed 174,000 votes in thirty-two states throughout thecountry. The sober Congressional Quarterly was moved to classify thefledgling Libertarian party as the third major political party in America.The remarkable growth rate of this new party may be seen in the fact thatit only began in 1971 with a handful of members gathered in a Coloradoliving room. The following year it fielded a presidential ticket whichmanaged to get on the ballot in two states. And now it is America’s thirdmajor party.Even more remarkably, the Libertarian party achieved this growthwhile consistently adhering to a new ideological creed—“libertarianism”—thus bringing to the American political scene for the first time in acentury a party interested in principle rather than in merely gaining jobsand money at the public trough. We have been told countless times bypundits and political scientists that the genius of America and of our partysystem is its lack of ideology and its “pragmatism” (a kind word forfocusing solely on grabbing money and jobs from the hapless taxpayers).How, then, explain the amazing growth of a new party which is franklyand eagerly devoted to ideology?One explanation is that Americans were not always pragmatic andnonideological. On the contrary, historians now realize that the AmericanRevolution itself was not only ideological but also the result of devotion tothe creed and the institutions of libertarianism. The Americanrevolutionaries were steeped in the creed of libertarianism, an ideology

2For a New Libertywhich led them to resist with their lives, their fortunes, and their sacredhonor the invasions of their rights and liberties committed by the imperialBritish government. Historians have long debated the precise causes of theAmerican Revolution: Were they constitutional, economic, political, orideological? We now realize that, being libertarians, the revolutionariessaw no conflict between moral and political rights on the one hand andeconomic freedom on the other. On the contrary, they perceived civil andmoral liberty, political independence, and the freedom to trade andproduce as all part of one unblemished system, what Adam Smith was tocall, in the same year that the Declaration of Independence was written,the “obvious and simple system of natural liberty.”The libertarian creed emerged from the “classical liberal” movementsof the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in the Western world, specifically, from the English Revolution of the seventeenth cent ury. Thisradical libertarian movement, even though only partially successful in itsbirthplace, Great Britain, was still able to usher in the IndustrialRevolution there by freeing industry and production from the stranglingrestrictions of State control and urban government-supported guilds. Forthe classical liberal movement was, throughout the Western world, amighty libertarian “revolution” against what we might call the OldOrder—the ancien régime which had dominated its subjects for centuries.This regime had, in the early modern period beginning in the sixteenthcentury, imposed an absolute central State and a king ruling by divineright on top of an older, restrictive web of feudal land monopolies andurban guild controls and restrictions. The result was a Europe stagnatingunder a crippling web of controls, taxes, and monopoly privileges toproduce and sell conferred by central (and local) governments upon theirfavorite producers. This alliance of the new bureaucratic, war- makingcentral State with privileged merchants—an alliance to be called“mercantilism” by later historians—and with a class of ruling feudallandlords constituted the Old Order against which the new movement ofclassical liberals and radicals arose and rebelled in the seventeenth andeighteenth centuries.The object of the classical liberals was to bring about individual libertyin all of its interrelated aspects. In the economy, taxes were to be drastically reduced, controls and regulations eliminated, and human energy,enterprise, and markets set free to create and produce in exchanges thatwould benefit everyone and the mass of consumers. Entrepreneurs were tobe free at last to compete, to develop, to create. The shackles of control

The Libertarian Heritage3were to be lifted from land, labor, and capit al alike. Personal freedom andcivil liberty were to be guaranteed against the depredations and tyranny ofthe king or his minions. Religion, the source of bloody wars for centurieswhen sects were battling for control of the State, was to be set free fromState imposition or interference, so that all religions—or nonreligions—could coexist in peace. Peace, too, was the foreign policy credo of the newclassical liberals; the age-old regime of imperial and State aggrandizementfor power and pelf was to be replaced by a foreign policy of peace andfree trade with all nations. And since war was seen as engendered bystanding armies and navies, by military power always seeking expansion,these military establishments were to be replaced by voluntary localmilitia, by citizen-civilians who would only wish to fight in defense oftheir own particular homes and neighborhoods.Thus, the well-known theme of “separation of Church and State” wasbut one of many interrelated motifs that could be summed up as“separation of the economy from the State,” “separation of speech andpress from the State,” “separation of land from the State,” “separation ofwar and military affairs from the State,” indeed, the separation of the Statefrom virtually everything.The State, in short, was to be kept extremely small, with a very low,nearly negligible budget. The classical liberals never developed a theoryof taxation, but every increase in a tax and every new kind of tax wasfought bitterly—in America twice becoming the spark that led or almostled to the Revolution (the stamp tax, the tea tax).The earliest theoreticians of libertarian classical liberalism were theLevelers during the English Revolution and the philosopher John Locke inthe late seventeenth century, followed by the “True Whig” or radicallibertarian opposition to the “Whig Settlement”—the regime of eighteenth-century Britain. John Locke set forth the natural rights of eachindividual to his person and property; the purpose of government wasstrictly limited to defend ing such rights. In the words of the Lockeaninspired Declaration of Independence, “to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from theconsent of the governed. That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or toabolish it ”While Locke was widely read in the American colonies, his abstractphilosophy was scarcely calculated to rouse men to revolution. This taskwas accomplished by radical Lockeans in the eighteenth century, who

4For a New Libertywrote in a more popular, hard- hitting, and impassioned manner andapplied the basic philosophy to the concrete problems of the government—and especially the British government—of the day. The mostimportant writing in this vein was “Cato’s Letters,” a series of newspaperarticles published in the early 1720s in London by True Whigs JohnTrenchard and Thomas Gordon. While Locke had written of the revolutionary pressure which could properly be exerted when governmentbecame destructive of liberty, Trenchard and Gordon pointed out thatgovernment always tended toward such destruction of individual rights.According to “Cato’s Letters,” human history is a record of irrepressibleconflict between Power and Liberty, with Power (government) alwaysstanding ready to increase its scope by invading people’s rights andencroaching upon their liberties. Therefore, Cato declared, Power must bekept small and faced with eternal vigilance and hostility on the part of thepublic to make sure that it always stays within its narrow bounds:We know, by infinite Examples and Experience, that Men possessed ofPower, rather than part with it, will do any thing, even the worst and theblackest, to keep it; and scarce ever any Man upon Earth went out of itas long as he could carry every thing his own Way in it. . . . This seemscertain, That the Good of the World, or of their People, was not one oftheir Motives either for continuing in Power, or for quitting it.It is the Nature of Power to be ever encroaching, and convertingevery extraordinary Power, granted at particular Times, and uponparticular Occasions, into an ordinary Power, to be used at all Times,and when there is no Occasion, nor does it ever part willingly with anyAdvantage .Alas! Power encroaches daily upon Liberty, with a Success tooevident; and the Balance between them is almost lost. Tyranny hasengrossed almost the whole Earth, and striking at Mankind Root andBranch, makes the World a Slaughterhouse; and will certainly go on todestroy, till it is either destroyed itself, or, which is most likely, has leftnothing else to destroy.1Such warnings were eagerly imbibed by the American colonists, whoreprinted “Cato’s Letters” many times throughout the colonies and down1See Murray N. Rothbard, Conceived in Liberty, vol 2, “Salutary Neglect”: TheAmerican Colonies in the First Half of the 18th Century (New Rochelle, N.Y.: ArlingtonHouse, 1975), p. 194. Also see John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon, Cato’s Letters, in D.L. Jacobson, ed. The English Libertarian Heritage (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Co.,1965).

The Libertarian Heritage5to the time of the Revolution. Such a deep-seated attitude led to what thehistorian Bernard Bailyn has aptly called the “transforming radicallibertarianism” of the American Revolution.For the revolution was not only the first successful modern attempt tothrow off the yoke of Western imperialism—at that time, of the world’smightiest power. More important, for the first time in history, Americanshedged in their new governments with numerous limits and restrictionsembodied in constitutions and particularly in bills of rights. Church andState were rigorously separated throughout the new states, and religiousfreedom enshrined. Remnants of feudalism were eliminated throughoutthe states by the abolition of the feudal privileges of entail andprimogeniture. (In the former, a dead ancestor is able to entail landedestates in his family forever, preventing his heirs from selling any part ofthe land; in the latter, the government requires sole inheritance of propertyby the oldest son.)The new federal government formed by the Articles of Confederationwas not permitted to levy any taxes upon the public; and any fundamentalextension of its powers required unanimous consent by every stategovernment. Above all, the military and war-making power of the na tionalgovernment was hedged in by restraint and suspicion; for the eighteenthcentury libertarians understood that war, standing armies, and militarismhad long been the main method for aggrandizing State power. 2Bernard Bailyn has summed up the achievement of the Americanrevolutionaries:The modernization of American Politics and government during andafter the Revolution took the form of a sudden, radical realization of theprogram that had first been fully set forth by the oppositionintelligentsia . . . in the reign of George the First. Where the Englishopposition, forcing its way against a complacent social and politicalorder, had only striven and dreamed, Americans driven by the sameaspirations but living in a society in many ways modern, and nowreleased politically, could suddenly act. Where the English oppositionhad vainly agitated for partial reforms . . . American leaders moved2For the radical libertarian impact of the Revolution within America, see Robert A.Nisbet, The Social Impact of the Revolution (Washington, D.C.: American EnterpriseInstitute for Public Policy Research, 1974). For the impact on Europe, see the importantwork of Robert R. Palmer, The Age of the Democratic Revolution, vol. I (Princeton, N.J.:Princeton University Press, 1959).

6For a New Libertyswiftly and with little social disruption to implement systematically theoutermost possibilities of the whole range of radically liberation ideas.In the process they . . . infused into American political culture . . . themajor themes of eighteenth-century radical libertarianism brought torealization here. The first is the belief that power is evil, a necessityperhaps but an evil necessity; that it is infinitely corrupting; and that itmust be controlled, limited, restricted in every way compatible with aminimum of civil order. Written constitutions; the separation ofpowers; bills of rights; limitations on executives, on legislatures, andcourts; restrictions on the right to coerce and wage war—all express theprofound distrust of power that lies at the ideological heart of theAmerican Revolution and that has remained with us as a permanentlegacy ever after. 3Thus, while classical liberal thought began in England, it was to reachits most consistent and radical development—and its greatest living embodiment—in America. For the American colonies were free of the feudalland monopoly and aristocratic ruling caste that was entrenched in Europe;in America, the rulers were British colonial officials and a handful ofprivileged merchants, who were relatively easy to sweep aside when theRevolution came and the British government was overthrown. Classicalliberalism, therefore, had more popular support, and met far lessentrenched institutional resistance, in the American colonies than it foundat home. Furthermore, being geographically isolated, the American rebelsdid not have to worry about the invading armies of neighboring,counterrevolutionary governments, as, for example, was the case inFrance.After the RevolutionThus, America, above all countries, was born in an explicitly libertarianrevolution, a revolution against empire; against taxation, trade monopoly,and regulation; and against militarism and executive power. Therevolution resulted in governments unprecedented in restrictions placed on3Bernard Bailyn, “The Central Themes of the American Revolution: An Interpretation,”in S. Kurtz and J. Hutson, eds., Essays on the American Revolution (Chapel Hill, NC.:University of North Carolina Press, 1973), pp. 26—27.

The Libertarian Heritage7their power. But while there was very little institutional resistance inAmerica to the onrush of liberalism, there did appear, from the verybeginning, powerful elite forces, especially among the large merchantsand planters, who wished to retain the restrictive British “mercantilist”system of high taxes, controls, and monopoly privileges conferred by thegovernment. These groups wished for a strong central and even imperialgovernment; in short, they wanted the British system without GreatBritain. These conservative and reactionary forces first appeared duringthe Revolution, and later formed the Federalist party and the Federalistadministration in the 1790s.During the nineteenth century, however, the libertarian impetus continued. The Jeffersonian and Jacksonian movements, the DemocraticRepublican and then the Democratic parties, explicitly strived for thevirtual elimination of government from American life. It was to be agovernment without a standing army or navy; a government without debtand with no direct federal or excise taxes and virtually no import tariffs—that is, with negligible levels of taxation and expenditure; a governmentthat does not engage in public works or internal improvements; agovernment that does not control or regulate; a government that leavesmoney and banking free, hard, and uninflated; in short, in the words of H.L. Mencken’s ideal, “a government that barely escapes being nogovernment at all.”The Jeffersonian drive toward virtually no government foundered afterJefferson took office, first, with concessions to the Federalists (possiblythe result of a deal for Federalist votes to break a tie in the electoralcollege), and then with the unconstitutional purchase of the LouisianaTerritory. But most particularly it foundered with the imperialist drivetoward war with Britain in Jefferson’s second term, a drive which led towar and to a one-party system which established virtually the entire statistFederalist program: high military expenditures, a central bank, a protectivetariff, direct federal taxes, public works. Horrified at the results, a retiredJefferson brooded at Monticello, and inspired young visiting politiciansMartin Van Buren and Thomas Hart Benton to found a new party—theDemocratic party—to take back America from the new Federalism, and torecapture the spirit of the old Jeffersonian program. When the two youngleaders latched onto Andrew Jackson as their savior, the new Democraticparty was born.The Jacksonian libertarians had a plan: it was to be eight years ofAndrew Jackson as president, to be followed by eight years of Van Buren,

8For a New Libertythen eight years of Benton. After twenty- four years of a triumphantJacksonian Democracy, the Menckenian virtually no-government idealwas to have been achieved. It was by no means an impossible dream, sinceit was clear that the Democratic party had quickly become the normalmajority party in the country. The mass of the people were enlisted in thelibertarian cause. Jackson had his eight years, which destroyed the centralbank and retired the public debt, and Van Buren had four, which separatedthe federal government from the banking sys tem. But the 1840 electionwas an anomaly, as Van Buren was defeated by an unprecedentedlydemagogic campaign engineered by the first great modern campaignchairman, Thurlow Weed, who pioneered in all the campaign frills—catchy slogans, buttons, songs, parades, etc—with which we are nowfamiliar. Weed’s tactics put in office the egregious and unknown Whig,General William Henry Harrison, but this was clearly a fluke; in 1844, theDemocrats would be prepared to counter with the same campaign tactics,and they were clearly slated to recapture the presidency that year. VanBuren, of course, was supposed to resume the triumphal Jacksonianmarch. But then a fateful event occurred: the Democratic party wassundered on the critical issue of slavery, or rather the expansion of slaveryinto a new territory. Van Buren’s easy renomination foundered on a splitwithin the ranks of the Democracy over the admission to the Union of therepublic of Texas as a slave state; Van Buren was opposed, Jackson infavor, and this split symbolized the wider sectional rift within theDemocratic party. Slavery, the grave antilibertarian flaw in thelibertarianism of the Democratic program, had arisen to wreck the partyand its libertarianism completely.The Civil War, in addition to its unprecedented bloodshed and devastation, was used by the triumphal and virtually one-party Republican regimeto drive through its statist, formerly Whig, program: nationalgovernmental power, protective tariff, subsidies to big business, inflationary paper money, resumed control of the federal government overbanking, large-scale internal improvements, high excise taxes, and, duringthe war, conscription and an income tax. Furthermore, the states came tolose their previous right of secession and other states’ powers as opposedto federal governmental powers. The Democratic party resumed itslibertarian ways after the war, but it now had to face a far longer and moredifficult road to arrive at liberty than it had before.We have seen how America came to have the deepest libertarian tradition, a tradition that still remains in much of our political rhetoric, and is

The Libertarian Heritage9still reflected in a feisty and individualistic attitude toward government bymuch of the American people. There is far more fertile soil in this countrythan in any other for a resurgence of libertarianism.Resistance to LibertyWe can now see that the rapid growth of the libertarian movement andthe Libertarian party in the 1970s is firmly rooted in what Bernard Bailyncalled this powerful “permanent legacy” of the American Revolution. Butif this legacy is so vital to the American tradition, what went wrong? Whythe need now for a new libertarian movement to arise to reclaim theAmerican dream?To begin to answer this question, we must first remember that classicalliberalism constituted a profound threat to the political and economicinterests—the ruling classes—who benefited from the Old Order: thekings, the nobles and landed aristocrats, the privileged merchants, themilitary machines, the State bureaucracies. Despite three major violentrevolutions precipitated by the liberals—the English of the seventeenthcentury and the American and French of the eighteenth—victories inEurope were only partial. Resistance was stiff and managed to successfully maintain landed monopolies, religious establishments, and warlikeforeign and military policies, and for a time to keep the suffrage restrictedto the wealthy elite. The liberals had to concentrate on widening thesuffrage, because it was clear to both sides that the objective economicand political interests of the mass of the public lay in individual liberty. Itis interesting to note that, by the early nineteenth century, the laissez- faireforces were known as “liberals” and “radicals” (for the purer and moreconsistent among them), and the opposition that wished to preserve or goback to the Old Order were broadly known as “conservatives.”Indeed, conservatism began, in the early nineteenth century, as a conscious attempt to undo and destroy the hated work of the new classicalliberal spirit—of the American, French, and Industrial revolutions. Led bytwo reactionary French thinkers, de Bonald and de Maistre, conserva tismyearned to replace equal rights and equality before the law by thestructured and hierarchical rule of privileged elites; individual liberty andminimal government by absolute rule and Big Government; religiousfreedom by the theocratic rule of a State church; peace and free trade by

10For a New Libertymilitarism, mercantilist restrictions, and war for the advantage of thenation-state; and industry and manufacturing by the old feudal andagrarian order. And they wanted to replace the new world of massconsumption and rising standards of living for all by the Old Order of baresubsistence for the masses and luxury consumption for the ruling elite.By the middle of and certainly by the end of the nineteenth century,conservatives began to realize that their cause was inevitably doomed ifthey persisted in clinging to the call for outright repeal of the IndustrialRevolution and of its enormous rise in the living standards of the mass ofthe public, and also if they persisted in opposing the widening of thesuffrage, thereby frankly setting themselves in opposition to the interestsof that public. Hence, the “right wing” (a label based on an accident ofgeography by which the spokesmen for the Old Order sat on the right ofthe assembly hall during the French Revolution) decided to shift theirgears and to update their statist creed by jettisoning outright opposition toindustrialism and democratic suffrage. For the old conservatism’s frankhatred and contempt for the mass of the public, the new conservativessubstituted duplicity and demagogy. The new conserva tives wooed themasses with the following line: “We, too, favor industrialism and a higherstandard of living. But, to accomplish such ends, we must regulateindustry for the public good; we must substitute orga nized cooperation forthe dog-eat-dog of the free and competitive marketplace; and, above all,we must substitute for the nation-destroying liberal tenets of peace andfree trade the nation- glorifying measures of war, protectionism, empire,and military prowess.” For all of these changes, of course, BigGovernment rather than minimal government was required.And so, in the late nineteenth century, statism and Big Governmentreturned, but this time displaying a proindustrial and pro-general- welfareface. The Old Order returned, but this time the beneficiaries were shuffleda bit; they were not so m

Rothbard, Murray Newton, 1926— For a new liberty. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Liberty. 2. Laissez-faire. 3. United States— Economic policy. 4. United States—Social policy. I. Title. JC599.U5R66 1978 320.5'I'0973 78-12225 ISBN -02-074690-3 Printed in the United States of America