Transcription

The GenogramWinifred Jolly, MSW, Jack Froom, MD, and Melville G. Rosen, MDS to n y B ro o k , N e w Y o rkThe genogram is presented as a technique to record both ge netic and interpersonal family-household data. Working withmodel patients, and using standard instructions and symbols,family medicine residents elicited and recorded an average of83 percent of available information items during interviewsthat lasted an average of 16 minutes. Interpretation of dataderived from genograms written by other physicians wasachieved with a high degree of accuracy (91 to 96 percentcorrect answers to 25 questions on each of three familyhouseholds). The genogram appears to be a practical instru ment to record and retrieve family-household data, but its wideapplication will require standardization of both the techniqueof recording and the symbols employed.The family physician optimally sees all mem bers of the same family or household. Regardlessof the number of members in a family attending thephysician’s practice, the physician has an interestin gathering both genetic and interpersonal data inaddition to the usual medical information. Thisenhances his/her understanding of the healthstatus of the family members and of the environ ment in which they live. For physicians who in clude family member’s charts in one folder, dataregarding related members of the family or house hold are usually obtained initially from one familymember. Additional family information is obtainedat the time of visits from other family members.A display of genetic as well as family historyand interactional information, along with signifi cant events, on a single diagram or “ genogram” 1From the Department of Family Medicine, State Universityof New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, New York. Re quests for reprints should be addressed to Ms. W inifredJolly, Department of Family Medicine, State University ofNew York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, NY 11794.is an attractive concept because retrieval of datamay be facilitated by this technique. The tech nique lends itself to rapid scanning by both thephysician and other health care providers, if thegenograms are uniformly coded. It reduces theneed for copious progress notes with copies ineach of the several family members’ charts. Inci dental illnesses of individuals need not be noted onthe genogram unless they constitute a crisis in thelife of that family; these notes more properly be long on the individual’s medical record chart.Medalie2 suggests separate use of the traditionalfamily tree and a “ psychofigure.” The family treedepicts several generations with sex, birth anddeath dates, and genetic diseases. The psycho figure describes interactions between the severalmembers of the household, including relationshipswhich are hostile, distant, discordant, and over involved.Gordon3 advises that a “ pedigree chart” bekept simple and short. Since this diagram is usedprimarily by geneticists, relatives by marriage areomitted because they are not genetically relevantto the analysis. Obviously, such omission is in-0094-3509/80/020251 -05 01.25 1980 Appleton-Century-CroftsTHE JOURNAL OF FAMILY PRACTICE, VOL. 10, NO. 2: 251-255, 1980251

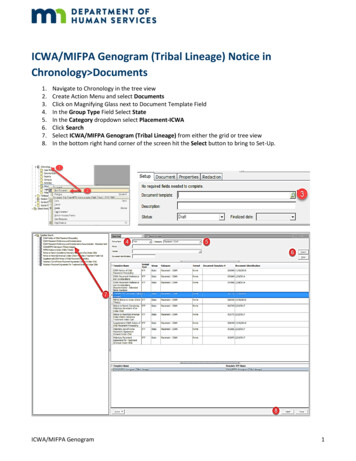

THE GENOGRAMNAME:CHART # :DATE:LINE D:LINE C:LINE B:LINE A:DYNAMIC CHANGESCRITICAL EVENTSFigure 1. G enogram fo rmappropriate for family physicians’ records becausethe presence of an illness or chronic conditionwithin a family or household network may alterthe balance of the relationships within that system.Hartman4 describes the use of a genogramwhich permits family therapists to record and readsocial and interactional data about three or fourgenerations of the family in order to illustrate thefamily’s system of functioning. The use of familyportraits is advocated by Cormack.5 He points outthat information about members of a familyhousehold is difficult to remember, especially re garding those members who are not personallyknown to the physician. Genetic and interactionalinformation about such absent members needs tobe noted and kept as available and current as thedata regarding the patient who makes regular orfrequent visits to the physician.252Despite numerous discussions in the literature,the actual utility and practicality of these varioustypes of recordings have not been studied, nor hasa standard method of recording been developed.This communication reports on the ability of ahealth care provider, in this case the family prac tice resident, to collect these data from pro grammed patients and measures the ability ofother health care providers to interpret the datathat have been so recorded.MethodsIn this pilot investigation, an attempt was firstmade to determine whether or not the genogramTHE JOURNAL OF FAMILY PRACTICE, VOL. 10, NO. 2, 1980

THE GENOGRAM MaleFemaleO o0 61—o —oQ -*—0 o roMarriageUnmarriedRelationshipDivorceSex notspecifiedAdoptedInduced s ofone householdDominant partner(in this case, )Identified patientIn household living away(school, jail, etc.)TwinsALCANEMIAARTHAlcoholAnemiaArthritisASTHB DEFECTGLAUCAsthmaBirth defectsGlaucomaBlood disorderCancerBLOOD DCAl HEARDMECZGl, GB, HEPGOUTHRT DIST CHOLt BPREN DISM RETARDM INEUROSISPSYCHOSISRFCONVULCVALUESt thy IDeafnessDiabetes mellitusEczemaGl tract, gall bladderand liver diseasesGoutHeart diseaseHypercholesterolemiaHypertensionKidney diseaseMental retardationMyocardial infarctionNeurosisPsychosisRheumatic feverSeizuresStrokeSyphilisThyroid, hyper orhypo activityF ig u re 2. G e n o g ra m s y m b o lscan be used to codify a useful amount of informa tion about a patient's family in a reasonable periodof time.Six family practice residents were given a blankgenogram (Figure 1) and legend (Figure 2) andbrief but specific instructions on the method ofrecording a genogram (available on request fromthe authors). Three patients were recruited andinstructed to respond only to the questions askedby the physician. Each patient was interviewed bythe six physicians who collected demographic, ge netic, and interpersonal information. Other medi cal data such as chief complaint, present illness,and review of systems were not obtained. Thetimes of the start and completion of the interviewTHE JOURNAL OF FAMILY PRACTICE, VOL. 10, NO. 2, 1980were recorded by the physician.The genogram and legend used in this studyconsist of the classical family tree and a specific,brief coded classification of diseases, health prob lems, social events, and family interactions. Acompleted genogram is illustrated in Figure 3. Thefamily described in this genogram shows the iden tified patient (IP) named Barbara, who presentedto the Family Health Center with aches, pains, andnonspecific symptoms. Figure 3 is a genogramdepicting the information obtained from Barbaraby the physicians in the study. Her family historyshows the presence of cancer (CA) and diabetesmellitus (DM) on her mother’s side, myocardialinfarction (MI) on both sides, and alcoholism253

THE GENOGRAMNAME:CHART # :1979-F u ll-tim e jobDA 11:1 9 7 5 :1.R Divorced1978: Ended unhealthy 3 -yr. relation ship with a manFigure 3. C om pleted g e n ogram fo r Barbara(ALC) in a sister and parent. Another sister, alongwith that sister’s son, had received a diagnosis ofneurosis. Barbara is not thought to have an affec tive disorder although a manic-depressive illnesshad earlier been considered among diagnosticpossibilities. The present household (shown by anunbroken circle) consists of Barbara and her twodaughters. After ten years of a conflictual relation ship (/w s ) wjth an alcoholic husband, Barbaraobtained a divorceBarbara’s husband re-254cently remarried and his new wife now appears tobe in conflict with the older daughter, who also hasconflict with her real mother, Barbara. Barbarahas an extremely close relationship with both herfather and her nephew ( ') .Critical events in the life of the patient and alsodynamic changes which have taken place since thepatient joined the family practice are noted.For the second part of the investigation, sixdifferent physicians were asked to read threeTHE JOURNAL OF FAMILY PRACTICE, VOL. 10, NO. 2, 1980

THE GENOGRAMgenograms completed by the investigators, and toanswer 25 questions about each of the families.ResultsThe average time required to record a genogramwas 16 minutes with a range of 9 to 30 minutes.The percent of information items elicited by eachof the physicians ranged from 66 to 93 percent,with an average score of 83 percent. These scoreswere derived by dividing the number of discreteinformation items obtained by the resident overthe total number of separate items obtained by allsix physicians for each of the patients.The six physicians who interpreted completedand standardized genograms showed little varia tion in their scores. For each of three patients, 25questions were asked, each requiring a true/falseanswer, and the correct numbers of answers wereconverted to a percentage score. The range ofscores was 91 to 96 percent, with an average scoreof 94.5 percent.tion, physician interviewing skills, and the natureof the relationship between the physician and thepatient. Nevertheless, findings from this prelimi nary study indicate that physicians can correctlyinterpret data recorded with the schema that isproposed. If this technique is to have wide appli cation, it will be necessary to derive standardsymbols to record the data. Agreement on such aclassification can best be achieved through an in terested organization, such as the North AmericanPrimary Care Research Group or the WorldOrganization of National Colleges, Academies andAcademic Associations of General Practitioners/Family Physicians (WONCA).The value of introducing this technique inpatient care has not yet been demonstrated, al though its informal usage at one residency pro gram appears to improve both patient care andphysician satisfaction. In the final analysis, theimpact of any intervention in a health care settingmust be measured by improved health status of thepatient and/or the family; studies designed tomeasure changes in outcome related to the use ofthe genogram are difficult but necessary if this newtechnique is to gain wide acceptance.DiscussionData from this preliminary investigation indi cate that the information required to complete agenogram may be elicited and recorded in about aquarter of an hour. It is anticipated that the lengthof time may be reduced as health care provid ers become more familiar with the technique. Onthe other hand, experience with “ unschooled” pa tients may demonstrate that a greater period oftime will be required to complete the form. Thecontinuity dimension of family medicine, how ever, permits small increments of time to be takenat each of several visits to complete the form.Although the model patients were instructed tofurnish information as freely as possible in areasthat are often sensitive, there was considerablevariation in recording of the data. Even greatervariation may be expected from actual patients,and will depend upon several variables which in clude patient comfort, sensitivity of the informa-1. Guerin PJ: Family Therapy: Theory and Practice.New York, Gardner Press, 19762. Medalie JH: Family Medicine: Principles and A ppli cations. Baltimore, W illiam s and Wilkins, 19783. Gordon H: The fam ily history and the pedigree chart.Postgrad Med 48:123, 19724. Hartman A: Diagrammatic assessment o f fam ily re lationships. Soc Casework 59:465, 19785. Cormack JJ: Family portraits: A method of recordingfam ily history. J R Coll Gen Pract 25:520, 1975THE JOURNAL OF FAMILY PRACTICE, VOL. 10, NO. 2, 1980255References

genograms completed by the investigators, and to answer 25 questions about each of the families. Results The average time required to record a genogram was 16 minutes with a range of 9 to 30 minutes. The percent of information items elicited by each of the physicians ranged from 66 to 93 percent, with an average score of 83 percent. These scores