Transcription

ReviewFatigue in rheumatic disease: an overviewFatigue is a common and disabling symptom in a number of rheumatic diseases, including rheumatoidarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and osteoarthritis. Patients frequently rank fatigue as one of their mostdisabling symptoms, adversely affecting quality of life and employment opportunities. The aims of thisarticle are to: first, define the concept of fatigue in rheumatic disease, its nature, prevalence and impact;second, describe questionnaires that have been validated as measures of fatigue among people withrheumatic diseases; third, outline the factors which have been identified as influencing fatigue, includingdisease activity/severity, disability, pain, sleep disturbance, mood, self-efficacy, illness perceptions andcoping; and finally, synthesize the sparse evidence currently available regarding the best strategies formanaging fatigue in rheumatic disease. Recent research has suggested that disease-modifying antirheumaticdrugs and biologic therapies are effective in ameliorating fatigue in both rheumatoid arthritis andankylosing spondylitis, but the mechanism by which they reduce fatigue is not clear. Tailored exercise andpsychological interventions show promise. Further studies are needed to determine the best ways ofmanaging the fatigue associated with rheumatic disease. The assessment of fatigue in rheumatology clinicsshould be part of standard practice.KEYWORDS: ankylosing spondylitis n fatigue n osteoarthritis n quality of lifen rheumatoid arthritisFatigue is a common symptom in many chronicdiseases. It can be defined as a state of ‘extremetiredness, typically resulting from mental orphysical exertion or illness’ [1] . This linguisticdefinition of fatigue is important because it islikely to form the basis of an individual’s understanding of the symptom. Alternative definitionsof fatigue were reviewed by Aaronson et al., whorecognized the challenges of defining fatiguegiven the complex interaction of biologicaland psychological processes, together with thebehavioral adaptations that are manifested [2] .Aaronson et al. described several published definitions of fatigue, including the comprehensivedefinition of fatigue as: “A subjective, unpleasantsymptom which incorporates total body feelings,ranging from tiredness to extreme exhaustion,creating an unrelenting overall condition whichinterferes with an individual’s ability to functionto their normal capacity” [3] . The suggestion thatfatigue is a continuum has been challenged byOlson [4] . Fatigue, tiredness and exhaustion havebeen found to be distinct states with specificclinical meaning at the ends of a continuum ofadaptation, where successful adaptation resultsin tiredness (which can be improved by sleep),and poor adaptation is associated with exhaustion, leading to impaired quality of life andsocial withdrawal [4] .Attempts have been made to define fatigue inthe specific context of arthritis [5] , where fatigueis recognized as a complex symptom, with bothphysical aspects (including need for rest andthe experience of weakness in muscles) andpsychological aspects (including problems withc oncentration) [6,7] .This article will address fatigue in three common rheumatic diseases, rheumatoid arthritis(RA), ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and osteoarthritis (OA), where fatigue has a considerable negative impact on quality of life [8,9] . The causes offatigue are multifactorial [7,10] . Many of the factorsleading to fatigue are common to all three conditions; however, the relative influence of contributing factors may differ across these diseases [8] .In undertaking this review, a range of literature databases were searched (includingPubMed, PsycINFO, Google Scholar and Webof Science) using terms to identify studies ofpeople with the rheumatic diseases in question(RA, AS, OA), relating to the concept ‘fatigue’(or the common antonym ‘vitality’) and with relevant methodologies (trial, randomized controltrial, longitudinal, diary, questionnaire, reliability). Reference lists and key journals (in particular, Rheumatology, Arthritis Care and Research,Journal of Rheumatology and MusculoskeletalCare) were also searched by hand.10.2217/IJR.10.30 2010 Future Medicine LtdInt. J. Clin. Rheumatol. (2010) 5(4), 487–502Simon Stebbings†& Gareth J Treharne1,21Department of Psychology, Universityof Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand2Department of Rheumatology, DudleyGroup of Hospitals NHS FoundationTrust, UK†Author for correspondence:Department of Medicine, DunedinSchool of Medicine, University of Otago,Dunedin, New ZealandTel.: 64 34 740 999Fax: 64 34 747 641simon.stebbings@otago.ac.nzISSN 1758-4272487

ReviewStebbings & TreharneThe importance of fatigue has recentlybeen recognized by the Outcome Measures inRheumatology (OMERACT) consortium [11] .OMERACT has endorsed the measurement offatigue in studies of RA wherever possible, concluding that fatigue is an important symptomthat is commonly reported by patients and isoften severe. Furthermore, several self-reportinstruments are available for reliably measuring fatigue, which provide valuable information additional to that obtained from otherc ommonly used outcome measures [12] .Nature of fatigueThe experience of fatigue in individuals withrheumatic diseases is very variable. However,when it is a prominent symptom it occurs onmost days and varies in intensity and frequencyranging from heaviness and weariness to exhaustion. Patterns of fatigue vary and a J-shapedcurve with levels decreasing in the morning andworsening in the evening has been reported inRA [13] .In qualitative studies of individuals with RA,patients distinguish between systemic fatigue,related to their arthritis, and general tiredness [14] . Fatigue frequently manifests not only asphysical fatigue, but also as an inability to thinkclearly, to concentrate or to motivate oneself [7] .Fatigue is experienced as variable and largelyunpredictable, often with sudden onset [15] .Occasionally, an abrupt onset of overwhelmingtiredness can occur, which forces people to stopwhat they are doing and lie down [16] . This characteristic aspect of fatigue has been described inRA, AS and OA [16–18] .Prevalence & severity of fatigueThe reported prevalence of fatigue in RA varieswidely depending on the criteria used, but theprevalence of clinically relevant fatigue is commonly given as between 40 and 80% [19–22] , with40% experiencing persistent severe fatigue [23] .Around a third of patients with AS suffersevere fatigue [24] , with an overall prevalenceof 53–76% [9,24,25] . In OA, the prevalence offatigue varies between 41 [19] and 56%, with10% e xperiencing severe fatigue [8] .Comparison between the levels of fatigueexperienced by individuals with different rheumatic diseases is also complicated by patientselection and particularly by the assessmenttools used. Comparison of fatigue using onemultidimensional tool, the MultidimensionalAssessment of Fatigue (MAF; scored 1–50 withhigher numbers indicative of worse fatigue) [26] ,488Int. J. Clin. Rheumatol. (2010) 5(4)across three forms of arthritis, has demonstratedsimilar levels of fatigue amongst people with RA(mean: 24.6–29.2; standard deviation [SD]:9.9–11.1), AS (mean: 28.3; SD: 14.2) and OA(mean 27.7; SD: 10.8) [8,20,25] . Using such measures, fatigue levels are similar to those observedin HIV-positive individuals and mothers nursingnewborn infants [27,28] .Impact of fatigueFatigue has a major social and economic costin rheumatic disease. Qualitative studies showthat social activities and household chores arecommonly affected by fatigue among peoplewith RA [12,15] or OA [18] . In one study of peoplewith RA, up to half the respondents questionedhad given up sports specifically owing to tiredness [15] . Fatigue and well-being were ranked asthe most important issues after pain and independence, and above joint symptoms, in a questionnaire (based on issues raised in focus groups)completed by 323 people with RA [29] .Rheumatic disease often impacts on the ability of an individual to maintain employmentfor diverse reasons. In one study of patientswith RA, 45% of participants cited fatigue asa persistent threat to employment [30] . Thesepatients had made a number of adaptations inorder to continue working, including changing jobs, altering their career path, changingworking hours and sleeping more [30] . Fatiguemay be a more important threat to employmentthan other factors, such as pain or psychologicalstress [31] . In an inception cohort of patients withRA (with a disease duration of 3 years) 27%of patients were found to be work-disabled. Inthis work-disabled subgroup, there was a strongassociation between loss of employment and anindicator of fatigue [32] .Work is an important element of healthrelated quality of life. Loss of employment andsubsequent detrimental effects on quality of lifeare greater in RA than AS. Fatigue has beenshown to have some contribution to this [33] .Employment is less indicative of quality of lifein OA, since patients tend to be older and theprevalence of OA increases with advancing age.However, OA is associated with significant lossof earnings in those below retirement age [34] .For people with OA, fatigue is described asdebilitating and occasionally restricting activity [32] . Some individuals link fatigue to pain,noting difficulties falling asleep or staying asleepand noting fatigue as a very negative aspectof their lives [35] . For people with AS, fatigueis an important and often under-recognizedfuture science group

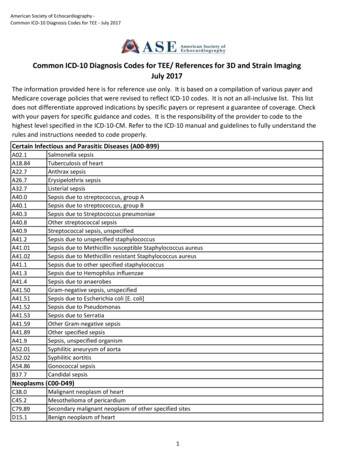

Fatigue in rheumatic disease: an overviewsymptom, which impacts on many differentaspects of an individual’s life, including physical functioning and relationships [36] . It can alsoimpact on daily working lives and on sport andleisure activities [17] . Fatigue is a strong predictorof work dysfunction and overall health status ina variety of rheumatic diseases including OAand RA [19] .Assessment of fatigueThe prevalence of fatigue is dependent on bothhow it is defined and how it is measured [19] .Since there are no definitive physiological orbiochemical markers of fatigue, accurate assessment relies on validated self-reporting measures [7] . Instruments for measuring fatiguecan be divided into single-item fatigue scales,Reviewgeneric multi-item fatigue scales and diseasespecific fatigue scales. There are advantages anddisadvantages to each of these three approachesto measurement. Neuberger [37] and Hewlettet al. [7] reviewed fatigue assessment scales usedin a variety of rheumatic diseases. More recentreviews of fatigue measures have tended tofocus on generic and specific fatigue measuresfor individual rheumatic diseases. An extensivereview of available fatigue measures used in studies amongst people with RA was carried out byHewlett et al. [38] . A review of fatigue scales hasbeen undertaken in AS by Zochling et al. [36] ,but no systematic review of different measuresof fatigue has yet been made in OA. A summaryof fatigue assessments that have been used inrheumatic disease is given in Table 1.Table 1. Summary of validated fatigue measures used in studies of rheumatic diseasesAssessment Studyof fatigueNumberof itemsUse inrheumaticdiseasesAdvantagesLimitationsSF‑36 VitalityWareet al.(1992)4RA, OA andASSmetset al.(1995)5RA/AS andASFACIT-FCella et al. 13(2005)Lack of vitality and fatigue areconceptually differentMay not differentiate depressionfrom fatigueNot developed for use inrheumatic diseaseSome items confounded by diseaseactivity and disabilityLimited evidence in RADeveloped for use in cancerpatients and some items may notbe relevant to rheumatic disease[24,42,44]MFIWidely used and allows directcomparison between manychronic conditionsSensitive to change in RAUsed in two large studies in ASFSSKruppet al.(1989)9AS[60,61]MAF-GFIBelzaet al.(1993)16RA, OA andASDeveloped for systemic lupuserythematosus and multiplesclerosis, with few data for otherconditionsLayout favors responses in terms ofdisability not fatigueLack of cognitive itemsVASEg/Wolfe(1996)1OA and RANRSNicklinet al.(2009)Garrettet al.(1994)3RA1ASBASDAI-VASRA and OAGood internal consistency,validity and sensitivity tochange in RAUsed in OAItems related to consequencesof fatigueComparable to SF‑36 in ASDeveloped specifically for RALarge body of published workin a variety of rheumaticconditionsEvidence for responsivenessEasy to administer in clinicsituationValid, reliable anddiscriminatoryResponsive to changeEasy to score and administerDeveloped specifically for usein RAWidely used and validatedLack of standardization betweenvarious VAS limits comparisonbetween studiesCan be time‑consuming to 41][56]Not yet fully validatedAbstracted from 6‑item diseaseactivity index and not designed foruse as a single scale[24,36,45]AS: Ankylosing spondylitis; BASDAI-VAS: Bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index-abstracted VAS; FACIT-F: Functional assessment of chronic illnesstherapy; FSS: Fatigue severity scale; MAF-GFI: Multidimensional assessment of fatigue scale (global fatigue index); MFI: Multidimensional fatigue inventory;NRS: Numerical rating fatigue scale; OA: Osteoarthritis; RA: Rheumatoid arthritis; SF‑36: Medical Outcomes Short form 36 (vitality scale); VAS: Visual analogfatigue scale.future science groupwww.futuremedicine.com489

ReviewStebbings & TreharneVisual analog fatigue scalesVisual analog fatigue scales (VAS; commonlya 10‑cm horizontal line with two descriptiveanchors) have been the most widely used, witha review showing 26 papers using these as aprimary fatigue measure in RA [38] . However,of these only three were identical in terms ofdescriptors, timescale and length [38] . Manystudies do not adequately describe the VAS used.This lack of standardization limits comparisonbetween different studies [38,39] . Three longitudinal studies have shown variation in fatigue overtime using a VAS, but reliability and sensitivitydata are inconsistent [38,40] .VAS have also been used to measure fatiguein OA. Again, there is considerable variationin scales used and the number of studies isfewer [19,41,42] . Levels of fatigue, where directlycompared using these scales, are similar to thosein patients with RA [19,43] .In AS, a VAS fatigue scale similar to those usedin the previously described studies has shown significant correlation with the Medical OutcomesStudies 36 item Short Form Questionnaire(SF‑36 [44]) [24] . However, in contrast to otherconditions, fatigue data in AS have commonlybeen abstracted from a component of the BathAnkylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index(BASDAI) [45] . This instrument consists of sixVAS questions and is used to assess self-evaluated disease activity. One of the questions comprises a 10‑cm VAS fatigue question regardingfatigue. Two large studies have employed thisscale to study fatigue in AS, one evaluating401 patients [46] and the other 812 patients [9] .Visual analog fatigue scales have a numberof advantages and have proved to be easy touse, valid, reliable and responsive for measuring a number of subjective experiences such aspain [47] and quality of life [48] as well as fatigue.They have greater discrimination than descriptive terms with numerical values (e.g., ‘mild’,‘moderate’ and ‘severe’) [47,48] . These propertieshave permitted the adoption of VAS scales ineveryday clinical use [49] . Indeed, VAS scaleshave been used in different forms for manyyears in clinical practice [50–53] . However, traditional VAS scales do require some prior patientinstruction and this can be time-consuming. Asa result, there has been a move towards substituting a numerical rating scale (NRS), whichdoes not appear to compromise the validity of anumber of widely used VAS scales and are mucheasier to score, explain and administer. NRSscales are now available for the component VASscales within the Western Ontario McMaster490Int. J. Clin. Rheumatol. (2010) 5(4)Universities’ Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC)and Bath Indices [54,55] . NRS versions of someassessments of fatigue in RA are available [56] ,with the potential benefit of relative ease ofcompletion compared with VAS, which can beconfusing for patients who have not previouslycompleted such scales.Multi-item fatigue scalesMulti-item scales seek to provide a multidimensional view of fatigue by measuring notonly the level of fatigue, but also its impacton areas such as quality of life and activitiesof daily living. Several such scales have beenused to measure fatigue in RA, even thoughthey were originally developed for use in otherconditions. Some of these have shown validity,internal consistency and sensitivity to change.However, as they were not designed to measurefatigue specifically in rheumatic disease, theysuffer from some limitations. By contrast, oneadvantage of generic scales is that they allowdirect comparisons between levels of fatigue indifferent conditions.Perhaps the most widely used generic multiitem fatigue scales is an element of the SF‑36.This questionnaire includes a four-item vitalitysubscale. Zautra et al. noted a strong negativecorrelation between the SF‑36 vitality subscaleand average levels of fatigue between individuals in both RA (r ‑0.60) and OA (r ‑0.46)populations [42] . The SF‑36 has also beenused to asses fatigue in AS, where it has beenshown to differentiate between fatigue levels inpatients with AS and healthy individuals [24] .Despite its widespread use, controversy surrounds the use of the SF‑36 as a fatigue measure, because some authors question whethera lack of vitality is a different conceptualexperience to fatigue [38] . Some studies haveshown that the SF‑36 vitality scale is sensitiveto change and has validity in RA [7] . Others,however, have demonstrated that patients withRA have more vitality than healthy individuals [38] . Furthermore, the SF‑36 vitality scalemay not differentiate depression from fatiguein RA [38] .The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory wasdeveloped to assess fatigue in cancer patients andpatients with chronic fatigue [57] . It consists offive subscales. Its use in rheumatic disease hasbeen limited with one study in AS and a comparison of fatigue in RA and AS [9,33] . Someitems may be confounded by disability and disease activity (e.g., ‘physically I feel only able todo a little’) [7] .future science group

Fatigue in rheumatic disease: an overviewThe Functional Assessment of Chronic IllnessTherapy (FACIT-F) is a 13‑item fatigue scale. Itwas also developed to measure fatigue in patientswith cancer, but has demonstrated good internalconsistency (Cronbach’s a 0.86–0.87), convergent validity and sensitivity to change in RA,where it also correlates with the MAF and SF‑36Vitality scale [58] . Its focus on cancer symptoms,which have not featured in qualitative analysesof patients with rheumatic disease (e.g., ‘I feeltoo tired to eat’) is a disadvantage [38] . It wasused in a study to evaluate fatigue in a trial ofthe biologic therapy with tocilizumab, wherea reduction in fatigue levels was demonstratedwith this therapy [59] . It was recently used in astudy of OA, where mean levels of fatigue werecomparable to those seen in RA [18] .The Fatigue Severity Scale is a nine-itemscale developed for use in multiple sclerosis andsystemic lupus erythematosus [60] . It has showngood internal consistency in these diseases.There are also items related to the consequencesof fatigue [37] . It has been used in AS and foundto be moderately responsive with good discriminative capacity and was comparable to the SF‑36vitality scale [61] .Assessments of fatigue developedspecifically for rheumatic diseasesThe Assessments of SpondyloArthritis Inter national Society (ASAS) has recommended thatfatigue be measured in studies of AS, but hasacknowledged that at present no specific toolexists to measure fatigue in AS [62] . For the timebeing, without a specific validated measure, ASAShas recommended using the fatigue measureincluded within the BASDAI [36] . The BASDAIincludes a single item (out of six) relating tofatigue. As noted previously, this item has beenabstracted to measure fatigue and has validity [24] .Given that there is considerable evidence forfatigue as an important symptom in OA [63] , itis perhaps surprising that standard instrumentssuch as the WOMAC, whilst assessing pain anddisability, do not include a fatigue measure. Nospecific measures of fatigue have been developedfor OA and it has not been included as a primaryoutcome measure by OARSI-OMERACT [64] . Multidimensional assessmentof fatigueOne of the most widely used fatigue scales inrheumatic disease is the MAF, which is usuallyexpressed as a total Global Fatigue Index (MAFGFI). The MAF was specifically adapted fromthe items of the Piper Fatigue Scale for use infuture science groupReviewRA [26] . The MAF-GFI scale contains 16 itemsmeasuring four dimensions of fatigue: severity,distress, degree of interference with activities ofdaily living and timing. The majority of itemsare answered on 10-point NRS with variousanchors (e.g., ‘Not at all’ to ‘A great deal’).MAF-GFI scores range from 1 (no fatigue)to 50 (severe fatigue) and samples of healthyindividuals have recorded scores with a meanbetween 15.8 and 17.0. The MAF-GFI has beenvalidated in samples of individuals affected byfatigue in a number of circumstances, including mothers nursing young infants and HIVinfected individuals [27,28,65] . The MAF hasgood internal consistency in both OA andR A (Cronbach’s a in R A 0.91–0.96) [20,65] .The MAF has been used to assess fatigue inOA [8] . It has been used but not validated inAS, where it does, however, correlate with theSF‑36 vitality scale [25] .Advantages of the MAF include a large bodyof published work showing its validity andresponsiveness, together with its wide applicability to different rheumatic conditions. The MAFhas been criticized for a layout favoring responsesin terms of disability rather than fatigue and alack of cognitive items [7] .Further specific scales for RA would be ofvalue given the limitations of the existing measures previously described. One set of measures, the Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue(BRAF) scales, uses either VAS or NRS to assessfatigue over three independent domains assessedas being relatively independent: level of fatigue,impact of fatigue and coping with fatigue [56] . Amultidimensional version of the BRAF has beendeveloped and is currently undergoing furthervalidation [66] . Fatigue diaries & momentary reportsSelf-report measures of fatigue typically involverespondents retrospectively averaging theirfatigue over a recall period of a number of daysor weeks. For example, both the MAF [26] andthe BRAF [56] were developed with a 7‑day recallperiod, which has been reported as the maximum length of time preferred by patients, inorder to allow them to think back about fatigueover a week’s routine structure [39] . Patients withrheumatic disease have, however, expressed theopinion that recalling symptoms like fatigueover a week overlooks the daily variation intheir symptoms [67] . Both paper and electronicdaily diaries have been shown to be feasible andacceptable to people with RA, with a preferencefor electronic formats [67] .www.futuremedicine.com491

ReviewStebbings & TreharneVAS and NRS measures of fatigue are common in studies using daily diaries. Heiberg et al.used a daily fatigue VAS with anchors ‘no fatigue’and ‘extreme fatigue’ in a study of people withRA [67] . Schanberg et al. applied a daily fatigueVAS with anchors ‘not tired’ and ‘very tired’ in astudy of children with juvenile arthritis [68] . Thesame daily fatigue VAS was asked seven-times aday in the study of juvenile arthritis [69] . In a studyby Stone et al., people with RA were also askedhow fatigued they felt on seven occasions over thecourse of a day and recorded this on a seven-pointNRS with anchors ‘not at all’ and ‘extremely’ [13] .Scores on this scale were worse following nightswith poor sleep, indicating predictive validity [13] .Similarly, in a study by Goodchild et al., peoplewith RA or Sjögren’s syndrome completed theProfile of Fatigue (ProF [6]) four times a day [70] .The ProF has validated momentary state andrecall versions and contains four items addressingmental fatigue and 12 items on somatic fatigueanswered on an eight-point NRS with anchors‘No problem at all’ and ‘As bad as imaginable’.Fatigue increased over the course of the day forthese participants, and afternoon fatigue levelson both subscales of the ProF were predicted bydiscomfort the p revious evening mediated bysleep disturbance [70] .Broderick et al. have adapted several questions about fatigue (or lack of vitality) [71,72] fromthe SF‑36 [73] and Brief Fatigue Inventory [74] .Questions were posed using a VAS answer format for momentary state and end-of-day ratings of fatigue (in addition to various periods ofrecalled ratings using the original NRSs). Theyfound that end-of-day ratings or 1‑day recallare an acceptable estimate of momentary staterating, particularly when the desired outcomemeasure is an average level of fatigue, but theyconclude that “patients have increasing difficultyactually remembering symptom levels beyondthe past several days,” reiterating the need fordaily assessment in studies of fatigue [72] .Physiological measures of fatigueFatigue can be defined as an increase in thephysiological cost necessary to realize a giventask [75] . For instance, there may be a higherperceived exertion or increased energy cost inwalking. Loss of strength and the inability tosustain a given level of submaximal resistance isanother potential measure of fatigue [75] .There have been few studies aimed at developing measures to test physiological fatigue inrheumatic disease. Neuberger et al. used testsof grip strength (using a syphgnomanometer), a492Int. J. Clin. Rheumatol. (2010) 5(4)bicycle ergonometer test and a timed 50‑ft walktest in a study comparing fatigue and aerobicfitness after an exercise intervention [76] .In a community-based elderly population,tests of physical performance have been adaptedand shown to be reliable and achievable measures. These include the ‘timed-up-and-go test’,‘sit-to-stand test’ and gait speed. As yet these havenot been used in studies of patients with rheumatic disease or compared with q uestionnairemeasures [77] .Activity ana lysis may provide information onphysiological fatigue. Spontaneous ambulatoryactivity has been measured using an accelerometer worn by the participant and has been shownto be a valid and reproducible measure that couldbe used to assess efficacy of an intervention [78] .Studies comparing activity with recalled ormomentary reports of fatigue in rheumatic disease have not been published to date, but as aproof of concept, fatigue diaries have been compared with activity, measured by a pedometer, inbreast cancer survivors [79] .Which factors influence fatigue?In the past, the complexity of the experience andthe difficulty in developing objective measuresfor fatigue led to the conclusion that studies intothe causes and severity of fatigue were not possible [80] . In the previous section, the variety ofvalidated fatigue measures has been outlined.The use of these various measurement tools hasallowed the investigation of factors that maycontribute to the experience of fatigue. Severalvariables appear to predict the severity of fatiguein rheumatic disease. These include diseaseactivity/severity, disability, pain, sleep disturbance, mood, self-efficacy, illness perceptionsand coping, as summarized in Table 2 . Physiological fatigueAs previously mentioned, the concept of fatigueencompasses physiological muscle fatigue, whichcan manifest as a decline in performance thatoccurs in any prolonged or repeated task, butcan occur earlier or be more severe or persistent in chronic illness. A reduction in activitymeasured by accelerometer has been demonstrated in patients with fibromyalgia and chronicfatigue [81] , but has yet to be compared withfatigue in RA or OA.In RA, fatigue, as measured by the MAF andphysiological measures (e.g., grip strength andtimed walk), improved following an exerciseprogram; however, these aspects of fatigue werenot directly compared [76] .future science group

future science groupRARARARAPhysiciandiagnosis ofarthritisSchanberget al. (2005)Schanberget al. (2000)Stone et al.(1997)Goodchildet al. (2010)Pollard et al.(2006)Strand et al.(2005)Minnock et al.(2009)Weinblattet al. (2003)Barlow et ed)www.futuremedicine.comRA or PSSRAJRD1111Numberof itemsFACIT-F or SF‑36vitality11-point NRSSF-36 vitalityVAS113 or 4141VAS (seven times1daily)Seven-point NRS1(seven times daily)ProF (four times daily; 16used in the afternoon)VAS (once daily)VASVASVASAssessment offatigueVAS423 (startingself-management orwaiting list)271 (starting TNFinhibitors)482 (startingDMARDs orplacebo)49 (starting TNFinhibitors)54 (startingDMARDs) or 30(starting TNFinhibitors)25 with RA13 with PSS35125171815114Sample size12 months24 weeks3 months6 months(DMARDs) or3 months(TNFinhibitors)1 year35 days7 days7 days2 months1 year2 years1 yearFollow-upAttending group self-management (one sessionper week for 6 weeks)Starting TNF inhibitor therapyGreater increase in patient global health (VAS)Greater decrease in pain (TJC)Starting TNF inhibitor therapyStarting DMARDsLess discomfort (ProD) the previous eveningLess sleep disturbance (sleep diary andactigraphy) the previous nightStarting DMARDs or TNF inhibitor therapyGreater decrease in disease activity (DAS)Greater decrease in pain (VAS)Better sleep quality (diary) the preceding nightHigher baseline inflammation (ESR)Perceiving their RA to have fewer consequences(IPQ) at baselineGreater self-efficacy for pain (ASES)Greater self-efficacy for mood/fatigue (ASES)Perceiving their R

488 Int. J. Clin. Rheumatol. (2010) 5(4) future science group Review Stebbings & Treharne Fatigue in rheumatic disease: an overview Review The importance of fatigue has recently been recognized by the Outcome Measures in