Transcription

SeminarRheumatic heart diseaseEloi Marijon*, Mariana Mirabel*, David S Celermajer, Xavier JouvenRheumatic heart disease, often neglected by media and policy makers, is a major burden in developing countrieswhere it causes most of the cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in young people, leading to about 250 000 deathsper year worldwide. The disease results from an abnormal autoimmune response to a group A streptococcal infectionin a genetically susceptible host. Acute rheumatic fever—the precursor to rheumatic heart disease—can affectdifferent organs and lead to irreversible valve damage and heart failure. Although penicillin is effective in theprevention of the disease, treatment of advanced stages uses up a vast amount of resources, which makes diseasemanagement especially challenging in emerging nations. Guidelines have therefore emphasised antibiotic prophylaxisagainst recurrent episodes of acute rheumatic fever, which seems feasible and cost effective. Early detection andtargeted treatment might be possible if populations at risk for rheumatic heart disease in endemic areas are screened.In this setting, active surveillance with echocardiography-based screening might become very important.IntroductionRheumatic heart disease is the result of valvular damagecaused by an abnormal immune response to group Astreptococcal infection, usually during childhood.1Although this disease—associated with poverty—hasalmost disappeared from wealthy countries, its burdenremains a major challenge in developing nations.2,3Preventive measures, based mainly on penicillin use andassociated with economic and social development, are veryefficient and have nearly eradicated rheumatic heartdisease in developed countries. However, according to the2008 Population Reference Bureau, about 80–85% ofchildren younger than 15 years (around 2 billion) live inareas where rheumatic heart disease is endemic.4Worldwide, this disease is the leading cause of heart failurein children and young adults, resulting in disability andpremature death and severely affecting the workforce inemerging nations.3 Demographic trends in the developingworld, including poor access to birth control and ruralexodus, will probably contribute to the substantial rise inthe number of people at risk for rheumatic heart disease inthe next 20 years.4 The disease receives little attention fromthe medical community, as shown by the low number ofpublications and congress presentations on this subject,and consequently is poorly covered by the media.Acute rheumatic fever usually occurs 3 weeks aftergroup A streptococcal pharyngitis and can affect thejoints, skin, brain, and heart.5 Around half of patientswith acute rheumatic fever present with cardiac inflammation mainly involving the valvular endocardium.6–11Although the initial attack can lead to severe valvulardisease, rheumatic heart disease most often results fromcumulative valve damage due to recurrent paucisymptomatic episodes of acute rheumatic fever, which suggeststhat it might be insidious at onset.3,5,12 Because secondaryprevention can prevent adverse outcomes, early echocardiography-based identification of silent rheumaticheart disease (showing no clinical signs) with minimalvalve lesions by active surveillance programmes might beof major importance.13–15In this Seminar we discuss epidemiology, pathophysiology, available preventive strategies, the rationalewww.thelancet.com Vol 379 March 10, 2012for and first experiences with echocardiography-basedscreening, and treatments for rheumatic heart disease.EpidemiologyImproved living conditions, nutrition, access to medicalcare, and penicillin use have substantially changed theepidemiology of acute rheumatic fever and rheumaticheart disease.3 Nevertheless, both prevail in developingnations and some underprivileged, mainly indigenous,populations in affluent countries.16,17 Carapetis andcolleagues3,18 have reviewed the worldwide burden ofthese diseases, but prevalence is difficult to estimate,mainly because of the scarcity of comprehensive diseaseregistries, the use of passive survey systems, and underreporting of acute and chronic cases.16,19Rheumatic heart disease causes at least 200 000–250 000premature deaths every year,3 and is the major cause ofcardiovascular death in children and young adults indeveloping countries.3,20 Epidemiological data for Africa arescarce, despite local efforts to raise awareness and tolaunch prevention programmes such as those outlined inthe Drakensberg declaration.21,22 In areas of poor or nomedical attention, the natural course of the disease prevailsbecause patients have no access to treatment. MortalityLancet 2012; 379: 953–64*Authors contributed equallyParis Cardiovascular ResearchCentre, INSERM U970(E Marijon MD, M Mirabel MD,Prof X Jouven PhD), andDepartment of Cardiology(E Marijon, Prof X Jouven),European Georges PompidouHospital, Paris, France; ParisDescartes University, Paris,France (E Marijon, M Mirabel,Prof X Jouven); Maputo HeartInstitute (ICOR), Maputo,Mozambique (E Marijon,Prof X Jouven); UniversityCollege London, London, UK(M Mirabel); and SydneyMedical School, University ofSydney, NSW, Australia(Prof D S Celermajer PhD)Correspondence to:Dr Eloi Marijon, ParisCardiovascular Research Centre,INSERM U970, Hôpital EuropéenGeorges Pompidou, 75737 Paris,CEDEX 15, Franceeloi marijon@yahoo.frSearch strategy and selection criteriaWe searched PubMed for publications in English with the terms “rheumatic heartdisease and epidemiology”, “rheumatic heart disease and pathophysiology”, “rheumaticheart disease and diagnosis”, “rheumatic heart disease and screening”, “rheumatic heartdisease and echocardiography”, “rheumatic heart disease and therapy”, “rheumaticheart disease and prevention”, and “rheumatic fever”. We focused on, but did notrestrict the search to, publications from the past 5 years. We selected relevant articlespublished in any language and have referenced several review articles and bookchapters, particularly on pathophysiology, because they provided comprehensiveoverviews that are beyond the scope of this Seminar. We also searched the Cochranedatabase with the term “rheumatic heart disease”, and our own database of referencesand those of linked articles in the searched journals. When more than one articlereferred to the same point, the most representative article was chosen. Regarding theacute phase of rheumatic heart disease (acute rheumatic fever), we describe only themost classic forms of presentation.953

Seminarrates in these areas can be as high as 20% at 6-year followup according to a Nigerian paediatric cohort study,23 or12·5% every year, as documented in rural Ethiopia.24Additionally, rheumatic heart disease causes substantial morbidity in children25 and adults, and can affectquality of life26 and economic growth. According to a2004 WHO report, the number of disability-adjustedlife-years lost to the disease was as high as 5·2 millionper year, worldwide.20The global incidence of acute rheumatic fever inchildren aged 5–14 years is roughly 300 000–350 000 peryear, although incidence varies substantially byregion.3,5,27 The yearly incidence of a first attack ofacute rheumatic fever ranges from 5 to 51 per100 000 population in Indigenous New Zealandcommunities, and can reach 80–254 per 100 000 inIndigenous Australian communities.28,29 Identifiedmodifiable risk factors for acute rheumatic fever includepoverty, overcrowding, malnutrition, and maternal educational level and employment.6,30–33 Virulence of streptococcal strains and genetic susceptibility might partlyaccount for the reported variations in acute rheumaticfever incidences worldwide.34,35According to traditional diagnostic criteria, 15·6–19·6 million people worldwide have rheumatic heartdisease.3 These data mainly originate from surveys ofschool children in whom diagnosis is made by clinicalassessment.20,32,36,37 Prevalence is highest in adults aged20–50 years.3,5,12 Distribution of rheumatic heart diseasevaries between continents, and sub-Saharan Africans andIndigenous Australians seem to have the highestprevalence.3,27,38,39 In Pacific Islanders and IndigenousAustralians, the prevalence is 5–10 per 1000 schoolchildren, and roughly 30 per 1000 adults aged35–44 years.17,37 In Asia, rheumatic heart disease prevalence varies,18—eg, in rural Pakistan it has a prevalence inthe community as high as 12 per 1000 people.40 In Southand Central America, rheumatic heart disease has a lowerreported prevalence (1·3 per 1000 school children).3The recent use of echocardiography-based screeningand the subsequent detection of silent cases is challengingthese traditional epidemiological data.13,14,41,42PathophysiologyThe pathogenesis of rheumatic heart disease results froman immune response consisting of humoral and cellularcomponents after exposure to Streptococcus pyogenes(classified as a group A streptococcus by the Lancefieldsystem), usually after a throat infection. The precisepathophysiology is obscure but several advances havenow been reviewed.34,43 Antigenic mimicry in associationwith an abnormal host immune response is thecornerstone of pathophysiology, based on the triad ofrheumatogenic group A streptococcal strain, geneticallysusceptible host, and aberrant host immune response.44,45Some strains are more likely to cause acute rheumaticfever than are others.5 S pyogenes contains M, T,954and R surface proteins, which are all associated withbacterial adherence to throat epithelial cells. The rheumatogenicity of some streptococcus families has traditionallybeen considered a feature of strains belonging to specificM serotypes. However, data show that rheumatogenicM serotypes were infrequently identified in communitieswith high burdens of acute rheumatic fever and rheumaticheart disease. These results question the potentialimportance of other disease-causing serotypes, especiallythose that cause streptococcal skin infections, whichmight be implicated in cases of acute rheumatic fever.46–48In 1889, Cheadle noted that the chance of an individualwith a family history of acute rheumatic fever acquiringthe disease is “nearly five times as great as that of anindividual who has no such hereditary taint”.49 Generally,HLA class II molecules (which participate in antigenpresentation to T-cell receptors) seem to be more closelyassociated with an increased risk of acute rheumaticfever or rheumatic heart disease than are class Imolecules, although no single HLA haplotype orcombination has been consistently associated withdisease susceptibility.34 The exact molecular mechanismby which HLA class II molecules confer susceptibility toautoimmune diseases is unknown.The role of autoimmune reactions in the pathogenesis ofacute rheumatic fever was substantiated when antibodiesagainst group A streptococcus reacted with human heartpreparations.50,51 After binding to the antigenic peptide, theparticular HLA complexes can initiate inappropriate T-cellactivation.52 Molecular mimicry takes place between streptococcal M protein and several cardiac proteins (cardiacmyosin, tropomyosin, keratin, laminin, and vimentin), anddifferent patterns of T-cell antigen cross-recognition havebeen identified.53,54 Mannose binding lectin (MBL) is anacute-phase inflammatory protein that functions as asoluble pathogen recognition receptor. MBL binds to a widerange of sugars on the surface of pathogens and plays amajor part in innate immunity because of its ability toopsonise pathogens, enhancing their phagocytosis andactivating the complement cascade via the lectin pathway.55One study reported that genotypes that correlated with highconcentrations of MBL were associated with rheumaticheart disease.56 Cytokines (interleukins 1 and 6, and tumournecrosis factor α [TNFα]) are thought to play a part in acuterheumatic fever, and the TNFα gene maps close to theMHC region; however, whether this association is relatedto other possible risk-associated genes is unclear.57Case-control association studies using a fine-resolutiongenome-wide approach should help to identify geneticvariants affecting individual susceptibility to rheumaticheart disease.35Natural history and presentationAcute rheumatic feverThe disorder manifests as a combination of fever, polyarthritis, carditis, chorea, erythema marginatum, andsubcutaneous nodules in patients about 3 weeks afterwww.thelancet.com Vol 379 March 10, 2012

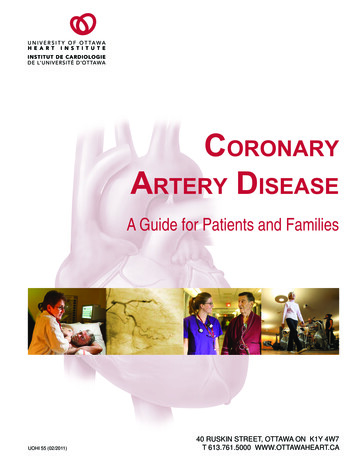

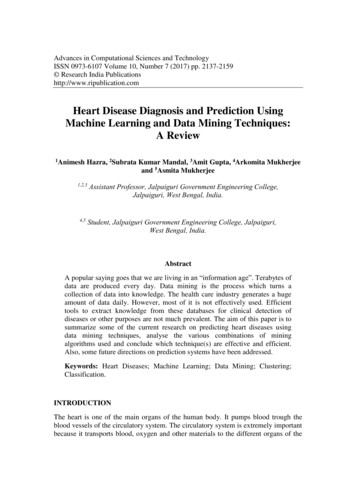

Seminarthey have had pharyngitis (most often paucisymptomaticor asymptomatic) caused by a group A streptococcalinfection (diagnosed by a positive throat swab culture ora high or rising streptococcal antibody titre), and mostoften affects children, adolescents, and young adults.5,58The clinical presentation of acute rheumatic fever variesand can be affected by delayed consultation or the use ofover-the-counter treatments such as anti-inflammatorydrugs. In 1944, Jones described the main clinical featuresof the disease, which have since been modified andrevised to become more stringent.59 Other criteria havebeen put forward to increase sensitivity and encourageinvestigators to standardise patients’ characteristicsunder the auspices of WHO and the National HeartFoundation of Australia and the Cardiac Society ofAustralia and New Zealand.5,60,61The peak incidence of acute rheumatic fever is inchildren aged 5–14 years. Arthritis is usually the earliestfeature of the disease, present in 60–80% of patients, andis often very painful and migratory, affecting mediumand large joints.5 Sydenham’s chorea presents later,usually between 1 and 6 months after the initial exposureto group A streptococcus, and manifests as involuntary,irregular movements, including fibrillatory tonguemovements, and spooning with external rotation of thehands. The proportion of patients with chorea variesconsiderably, from 7% to 28% in different settings.58,62Cutaneous manifestations are rare and sometimesdifficult to diagnose.Carditis occurs a few weeks after the initial infection inabout 50% of patients with acute rheumatic fever, andpresents as valvulitis, sometimes combined with pericarditis or (more contentiously) myocarditis.8,63 Patientsare examined for various hallmarks of acute carditis, suchas sinus tachycardia (particularly its persistence at night)and a diminished first heart sound caused by a frequent,extended PR interval, verified by electrocardiography.59,64A soft, blowing, pansystolic murmur is characteristic ofmitral regurgitation and strongly suggests rheumaticvalvulitis. Pericarditis is common in acute rheumaticfever, and is characterised by chest pain and a transientpericardial friction rub accompanied by a small pericardialeffusion on echocardiogram. A very large effusion causingcardiac tamponade is rare. Signs of poorly toleratedvalvular regurgitation include a prominent left ventricular impulse due to dilatation, and signs of left or rightheart failure. A chest radiograph might show cardiacenlargement or signs of congestive heart failure.Minich and colleagues65 were among the first todescribe subclinical carditis in children. In their cohort,several patients with no murmur had echocardiographicfindings consistent with pathological mitral regurgitation,65 a result supported by many others.7,11Rheumatic heart diseasePatients might be diagnosed with rheumatic heart diseaseafter a known acute rheumatic fever attack; however, thewww.thelancet.com Vol 379 March 10, 2012disease is often diagnosed in patients who were previouslyasymptomatic or who do not recall acute rheumatic feversymptoms or episodes. Most patients present after theonset of shortness of breath at ages 20–50 years.12 Althoughcontroversy exists about the female predominance of acuterheumatic fever,29 women of childbearing age do have ahigher prevalence of established rheumatic heart diseasethan do men.12,40 Researchers have not fully addressed thereasons for this female predominance, but some haveproposed that social factors (such as child rearing, whichmight result in repeated exposure to group A streptococcus), access to health care (especially preventive medicine), and genetically-mediated immunological factorsthat predispose women to autoimmune diseases mightbe associated.Clinical diagnosis is based on pathological valvularheart murmur detected during auscultation. Mitral valveincompetence is the most common valvular lesion inpatients with rheumatic heart disease, particularly in theearly stages.8,66 Mitral stenosis usually develops later as aresult of persistent or recurrent valvulitis with bicommissural fusion,67 although mitral stenosis has beendescribed in adolescents.66,68 Patients with mitralincompetence can remain asymptomatic for up to10 years as a result of compensatory left atrial and leftventricular dilatation before the onset of left ventricularsystolic dysfunction. Aortic regurgitation is most oftenassociated with some degree of mitral regurgitation, butcan be isolated and severe. Tricuspid regurgitation isoften functional, mainly caused by mitral stenosis withhigh pulmonary pressures and consequent rightventricular dilatation.69 Isolated pulmonary or tricuspidregurgitation are not classic features of rheumatic heartdisease. The disease might also present after acomplication such as atrial arrhythmia, an embolic event,acute heart failure, or infective endocarditis.Echocardiography is used to link murmurs detectedduring auscultation to their cause. Typically, morphological changes of the mitral valve include leafletthickening, subvalvular apparatus thickening, shortenedchordae tendineae, commissural fusion, calcification,and restricted leaflet motion (figure 1). Some degree ofcommissural fusion is always present in rheumaticmitral stenosis (figure 2).67 The aortic valve might havethickened cusps with rolled edges.The natural course of severe valvular disease leads tosevere heart failure in the absence of appropriateintervention. In very advanced stages of the disease,surgery might become contraindicated when myocardialdilatation and dysfunction prevail.70 Unfortunately, manypatients present too late, especially in remote areas.Preventive strategiesPrevention strategies are the most appealing option forsustainable disease control in developing nations.Medical intervention is based on the eradication of groupA streptococcus with penicillin, which prevents the initial955

SeminarAAnterior mitral leafletBPosterior mitral leafletRVAoLVLAFigure 1: Transthoracic echocardiography of symptomatic rheumaticmitral stenosis(A) Parasternal short axis view showing thickened anterior mitral leaflet(asterisk), bicommissural fusion (arrows), and restricted mitral leaflet motion,which are all features of mitral stenosis. (B) Parasternal long axis view withanterior (asterisk) and posterior mitral leaflet thickening, subvalvular apparatusfusion and shortening, restricted bileaflet motion with classic dog-leg deformityof the anterior mitral leaflet, and left atrium dilatation. Ao aorta. LA leftatrium. LV left ventricle. RV right ventricle.acute rheumatic fever attack (primary prophylaxis) ordisease recurrences (secondary prophylaxis). The efficacyand safety of antibiotic prophylaxis are well established,and should lead to near complete eradication of advancedrheumatic heart disease when combined with broaderchanges such as improved living conditions, education,and awareness.71–73Community-based preventionPrimordial prevention—ie, elimination of risk factorswithin the community at the earliest stage—is linkedto socioeconomic development, which directly affectshygiene, access to medical care, and living conditions. Indeveloped nations, the decrease in acute rheumatic feverincidence started before the antibiotic era and has beenattributed to better living conditions in the USA andwestern Europe.74 Although some countries have achievedmajor economic development, access to hygiene andpublic health measures are often inequitable acrosspopulations.75 In any case, economic improvement does956Figure 2: Macroscopic view of a rheumatic mitral valveTypical features of advanced rheumatic valve disease such as bicommissuralfusion (arrow) and retraction of the anterior mitral leaflet are shown. Imagecourtesy of Stéphane Aubert, Clinique Ambroise Paré, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France.not provide complete protection against acute rheumaticfever and rheumatic heart disease, as shown by diseaseoutbreaks in middle-class children in the USA in the1990s and in northern Italy more recently.58,76Primary preventionIdeally, prophylaxis should prevent the first acuterheumatic fever attack, particularly if given shortly after asore throat.2,77 Primary prevention relies on the eradicationof group A streptococcal carriage through active sorethroat screening and by treatment of pharyngitis by oralantibiotics (phenoxymethylpenicillin 250 mg two or threetimes daily for patients weighing 27 kg, phenoxymethylpenicillin 500 mg two or three times daily forpatients weighing 27 kg; or amoxicillin 50 mg/kg perday for 10 days) or intramuscular antibiotics (benzathinebenzylpenicillin 600 000 IU [one injection] for patientsweighing 27 kg, or 1 200 000 IU [one injection] forpatients weighing 27 kg).78 So far, primary preventionalone as a large-scale strategy has often been neglected indeveloping countries.79 Programmes that target subpopulations with a high prevalence of rheumatic heartdisease might be more efficient than present practices.80A systematic review of primary prevention showed anoverall benefit, with one case of acute rheumatic feverprevented for 53 sore throats treated;81 this finding wassupported by a meta-analysis by Lennon and colleagues.82However, these results are somewhat controversialbecause a randomised controlled trial from New Zealandof 24 000 children did not show a decrease in acuterheumatic fever incidence after implementation of thiswww.thelancet.com Vol 379 March 10, 2012

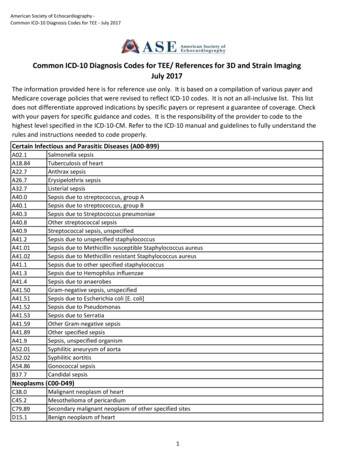

Seminarstrategy.83 The diagnosis of group A streptococcalpharyngitis is difficult on clinical grounds alone andneeds microbiological confirmation.78 However, laboratory analysis is rarely available in developing countries.Two other fundamental limitations of primary preventionstrategies are the existence of asymptomatic throatinfection complicated by an inflammatory response, andthe possibility of other sites of pathogenic infection (suchas skin).84,85Another possibility for primary prevention is vaccinedevelopment. Research initially focused on targeting thevariable region of the M protein.86 Investigators havecompleted phase 2 trials of a multivalent M-type-specificvaccine in adults, and have reported evidence of safetyand immunogenicity.87 However, most vaccine developments have targeted strains prevalent in low-risk areassuch as North America. Ubiquitous vaccines using highlyconserved antigens would be the ideal solution. Althoughresearch remains active, vaccines are not scheduled to beintroduced to the market in the foreseeable future.88Secondary preventionSecondary prevention attempts to reduce the acquisition ofnew group A streptococcal strains that might inducerepeated or chronic acute rheumatic fever attacks, and isa major determinant of cardiac outcome.89,90 Someresearchers recommend one intramuscular injection ofbenzathine benzylpenicillin in patients every 3–4 weeksafter an acute rheumatic fever attack, rather than oraltreatment, because of its proven efficacy and compliance(table).92 The duration of secondary prophylaxis dependson the patients’ age, the date of their last attack, and mostimportantly the presence and severity of rheumatic heartIntramuscularbenzathinebenzylpenicillindose by patientweightInterval ofbenzathinebenzylpenicillininjectionsdisease. In some highly endemic regions, risk of recurrenceis high, and some institutions have recommended longterm or lifelong prophylaxis for patients with severerheumatic heart disease or previous valvular surgery.2,60,78,91Secondary prophylaxis is more efficiently deliveredwithin community-based registry programmes than inareas that have no registry.93 Poor compliance withsecondary prophylaxis (as low as 50% in somecampaigns94,95) has been an issue in several programmes,mainly because of the mobility of the target population,understaffing, and remote settings.96 Education, use ofhealth workers with strong local community links, andintegration into existing primary-care networks areparamount to improve the efficiency of community-basedsecondary prevention programmes.97,98Cost-effectiveness and global resultsAssessment of the cost-effectiveness of preventivestrategies is difficult and data can seldom be translatedfrom one region or timeframe to another. Analyses haveshown several primary prophylaxis campaigns to be costeffective in developed countries, although the campaignsdo use a substantial amount of resources.99,100 In SouthAfrica, the cost per prevented episode of acute rheumaticfever has been estimated at US 46.81,101Secondary prophylaxis is thought to be the most costeffective intervention.102,103 In a large multicentre programme of secondary prophylaxis undertaken by WHO,cost-effectiveness was assessed by the number of hospitaldays averted. The penicillin cost was considerablyoutweighed by the reduction in the number ofhospital days that patients needed.94 In New Zealand, thecost of an efficient secondary prevention programmeOral alternative treatments (dose)DurationNo carditis: for 5 years or until 18 years of age*;resolved carditis†: for 10 years or until at least25 years of age*; moderate to severe RHD or surgery:lifelongWHO, 20012 30 kg: 600 000 IU; 21 days if high 30 kg: 1 200 000 IU risk; 28 days iflow riskPhenoxymethylpenicillin (250 mg twicea day); sulphonamide ( 30 kg: 500 mgdaily; 30 kg: 1000 mg daily);erythromycin (250 mg twice a day)Australia, 200660 20 kg: 600 000 IU; 28 days; 21 days 20 kg: 1 200 000 IU if high risk‡Phenoxymethylpenicillin (250 mg twice a No carditis: for 10 years or until 21 years of age*;day); erythromycin (250 mg twice a day) resolved carditis or mild RHD: for 10 years or until21 years of age*; moderate RHD: until 35 years of age;severe RHD or surgery: until at least 40 years of ageIndia, 200891 27 kg: 600 000 IU; 15 days if 27 kg; Phenoxymethylpenicillin (250 mg twice 27 kg: 1 200 000 IU 21 days if 27 kg a day in children; 500 mg twice a day inadults); erythromycin (20 mg/kg;maximum dose 500 mg)No carditis: for 5 years or until 18 years of age*; mildto moderate carditis or healed carditis: for 10 yearsor until 25 years of age*; severe RHD orpostintervention: lifelong or until 40 years of ageUSA, 200978 27 kg: 600 000 IU; 28 days; 21 days Phenoxymethylpenicillin (250 mg twicea day); sulphonamide ( 27 kg: 500 mg 27 kg: 1 200 000 IU if havingrecurrent attacks daily; 27 kg 1000 mg daily); macrolide(dose variable)No carditis: for 5 years or until 21 years of age*;resolved carditis: for 10 years or until 21 years ofage*; RHD: for 10 years or until 40 years of age*;consider lifelong if high riskBenzathine benzylpenicillin is the preferred antibiotic according to all guidelines. RHD rheumatic heart disease. *Whichever is longer. †Healed carditis or mild mitralregurgitation. ‡For moderate to severe carditis, valve surgery is recommended if the patient has good adherence to monthly treatment, or after recurrence despite monthlyinjections.Table: International recommendations for secondary prophylaxis of acute rheumatic feverwww.thelancet.com Vol 379 March 10, 2012957

Seminaraccounted for only 13% of the total budget allocated toacute rheumatic fever.104The campaign against rheumatic heart disease needs astrong political will, driven by the awareness andlobbying capacity of health carers. The principles thatunderlie control of this disease in highly resourcednations might not apply to developing countries. Wherehealth-care finances are very scarce and health is oftenprovided by non-governmental organisations (NGOs),rheumatic heart disease might not be perceived as apriority. Three successful approaches originating fromCentral America and the Caribbean, in differenteconomic and political contexts, showed the efficiency ofcombined strategies consisting of education and primaryand secondary prophylaxis (figure 3).30,72,73Surveillance in rheumatic heart diseaseThe aims of surveillance (either passive or active) are toprovide accurate estimates of disease burden and to allowinitiation of preventative therapy for as many affectedpeople as possible.Passive surveys rely on identification of cases ofdiagnosed rheumatic heart disease in a predefinedpopulation, and can be done retrospectively. HospitalFigure 3: Poster to raise awareness of rheumatic fever in the low-incomeCaribbean island of Santa LuciaHealth authorities achieved success by redistributing part of the budget forrheumatic heart disease, taking some away from cardiac surgery and putting ittowards a control programme for acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heartdisease, which included primary and secondary prophylaxis. Image courtesy ofXavier Jouven, HÔpital Européen Georges Pompidou.958and primary-care facilities should both be surveyed todetect the largest number of cases, and accuratedemographic data are needed. Case ascertainment mightbe improved if there are existing registers, althoughunder-reporting usually occurs.19Active screening has important methodologicaladvantages because it consists of cross-sectional surveysto detect previously unknown cases, avoiding biasinduced by asymptomatic cases or poor access to healthservices, and usually leading to higher prevalence orincidence estimates than with passive screening.27 Therationale for active surveillance is not only to provide themost accurate epidemiological data of the disease butalso to offer early treatment to those affected, especiallythe large proportion of asymptomatic patients who mightsubsequently develop advanced disease.The Council of Europe and WHO recommendscreening programmes for preventable diseases.105,106 In1984, WHO initiated a programme that screened about15 million children for rheumatic heart disease across16

Rheumatic heart disease Eloi Marijon*, Mariana Mirabel*, David S Celermajer, Xavier Jouven Rheumatic heart disease, often neglected by media and policy makers, is a major burden in developing countries where it causes most of the cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in young people, leading to about 250 000 deaths per year worldwide.